Stanford CS231N Deep Learning for Computer Vision | Spring 2025 | Lecture 1- Introduction

- Course introduction and instructors

- Computer vision positioned within AI and deep learning defined

- Course scope and expectations overview

- Evolutionary origins of vision and its link to intelligence

- Human visual system, cameras, and the need for visual intelligence

- Hubel and Wiesel neural receptive fields and hierarchical vision

- Early computational vision research and its historical milestones

- David Marr’s representational stages and the ill-posed nature of 3D recovery

- Comparing language and vision; implications for generative models

- Progress through the 1970s–1980s, AI winter, and cognitive neuroscience guidance

- Psychophysical evidence of rapid and contextual visual processing

- Feature engineering, face detection, and the emergence of web-scale datasets

- Historical roots of neural architectures and the neocognitron

- Backpropagation and its role in training neural networks

- Early applied convolutional networks and the data bottleneck

- ImageNet, large-scale benchmarks, and the 2012 inflection point

- Post-ImageNet advances across vision tasks and model families

- Generative models, image captioning, and the rise of vision generative AI

- Compute and hardware acceleration driving model scaling

- Ethical considerations, biases, and human-centered applications

- Course goals and high-level topic categorization

- Image classification as a foundational computer vision task and linear baselines

- Neural networks and stacking layers to model nonlinear functions

- Defining vision tasks: semantic segmentation, object detection, instance segmentation

- Temporal and multimodal vision tasks and model interpretability

- Core model families: convolutional networks, recurrent networks, and transformers

- Large-scale distributed training and system-level considerations

- Self-supervised and generative modeling approaches

- Vision-language models and cross-modal representations

- 3D vision and embodied agents for grounded understanding

- Awards, learning objectives, and next lecture preview

Course introduction and instructors

The course begins by introducing the instructor and teaching team to establish responsibilities and points of contact for students.

Key administrative details:

- Multiple co-instructors and teaching assistants who will lead lectures, laboratories, and student support.

- Explicit points of contact for course materials, questions, and office hours.

- Expectations for course communication and collaboration channels (lectures, labs, discussion sections).

This administrative context frames how students should seek help and how the course will be staffed throughout the quarter, signaling the start of a structured technical curriculum in computer vision and deep learning.

Computer vision positioned within AI and deep learning defined

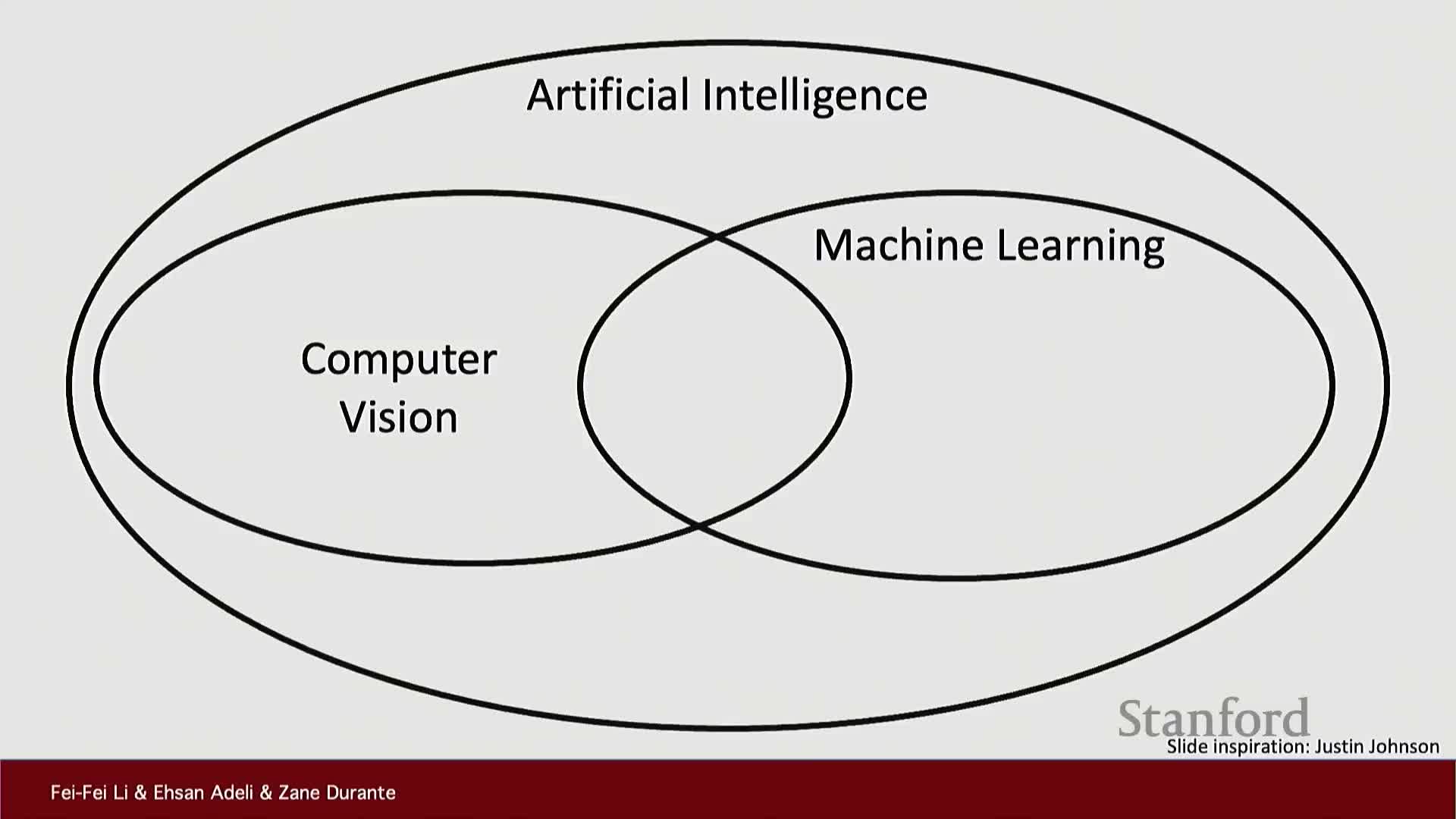

Computer vision is framed as an integral, foundational subfield of artificial intelligence that interfaces with many other scientific disciplines.

- Deep learning is defined as a family of algorithmic techniques built around artificial neural networks, and credited with driving recent revolutions in AI.

- The course scope is the core intersection of computer vision and deep learning, not a broad survey of all AI topics.

- Emphasis is placed on both theoretical and applied aspects: algorithmic principles, architectures, and applications central to modern visual intelligence.

Course scope and expectations overview

The instructors clarify that the course will not cover all of computer vision or machine learning, but will focus on their core intersections.

- Subsequent instructors will detail course structure, assignments, and evaluation, establishing pedagogical expectations.

- Students should expect technical material centered on visual recognition, model building, and practical application of deep learning methods.

- The curriculum mixes theory, implementation, and application-driven learning to develop both understanding and skills.

Evolutionary origins of vision and its link to intelligence

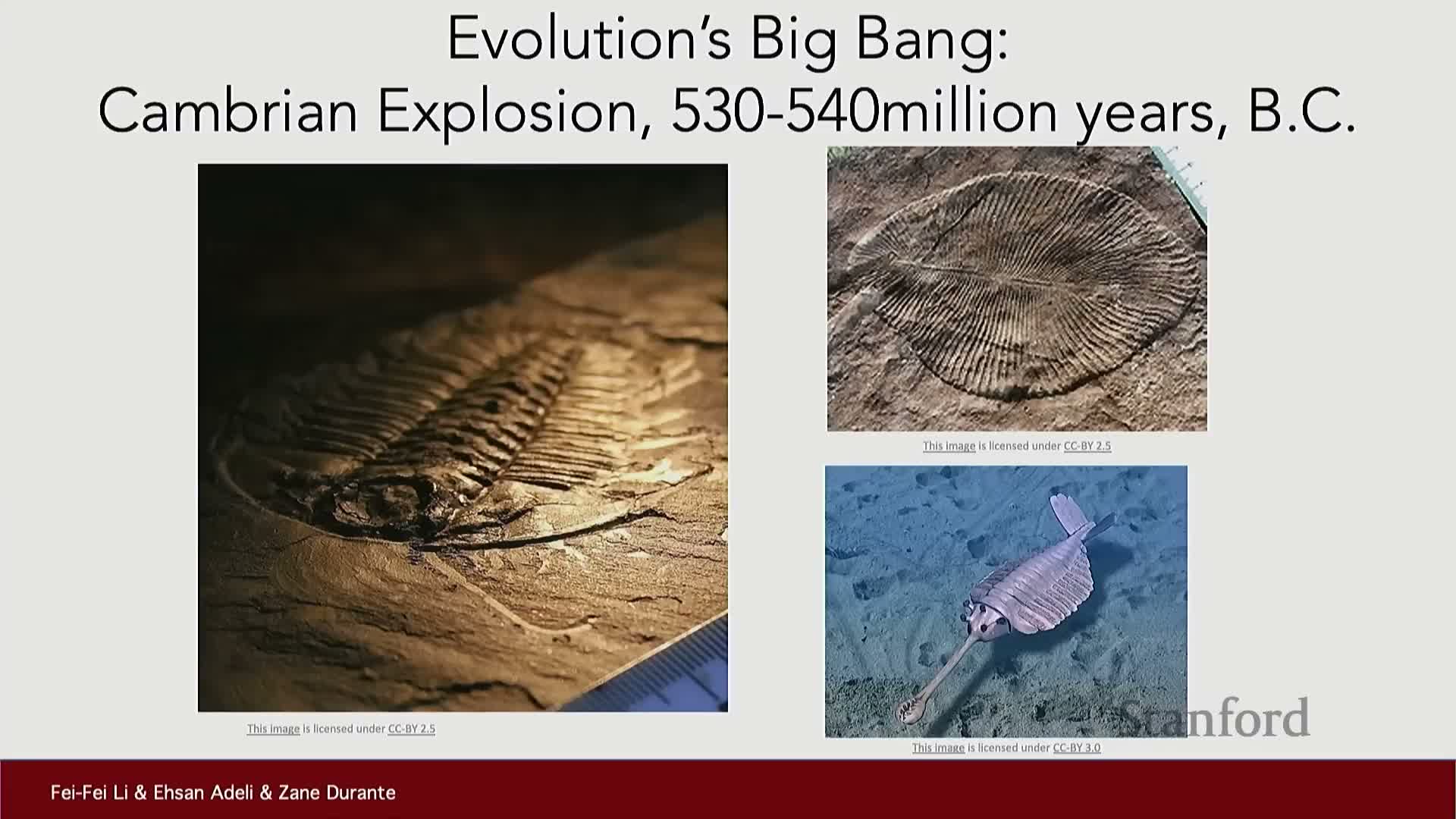

Vision is placed in an evolutionary context, traced back to the Cambrian explosion (~540 million years ago) to explain the rise of photosensitive organs.

- Early light-sensitive cells provided an information channel that transformed passive metabolism into active interaction with the environment.

- This sensory input created selective pressures that drove nervous-system and behavioral complexity.

- Vision and tactile sensing are among the oldest animal senses, and visual capability co-evolved with neural architectures for complex perception and decision-making.

- The evolutionary perspective motivates studying vision as a core facet of intelligence.

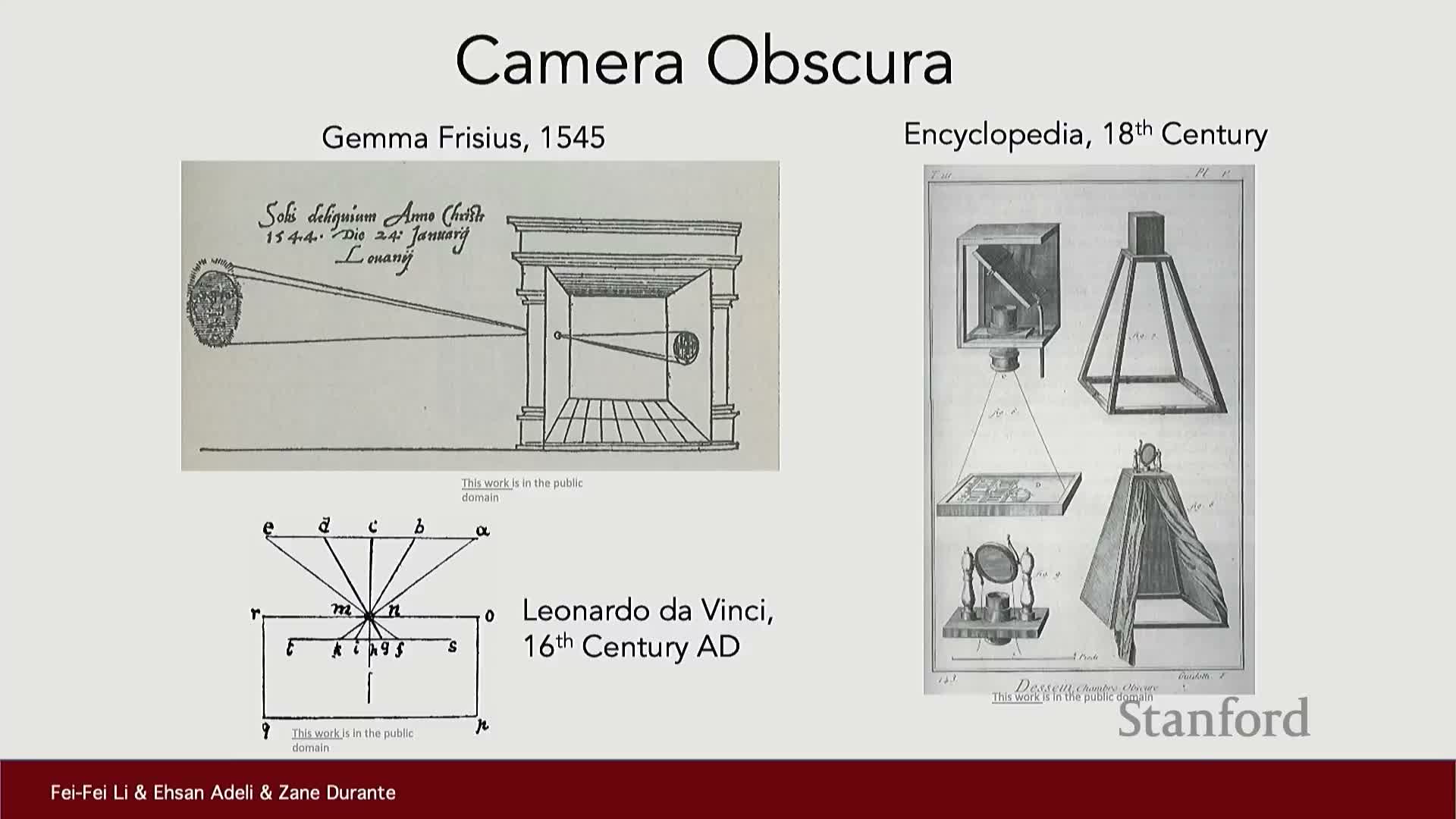

Human visual system, cameras, and the need for visual intelligence

The lecture contrasts biological vision with engineered optical devices to emphasize that sensing alone does not equal understanding.

- Cameras and eyes are both sensing apparatuses, but do not by themselves produce visual understanding.

- Historical efforts—camera obscura and Leonardo da Vinci’s studies—illustrate longstanding engineering interest in image formation.

- The central technical challenge of computer vision is converting pixel data into representations and decisions via computational models and algorithms.

- This explains why research focuses on perception and inference beyond optics.

Hubel and Wiesel neural receptive fields and hierarchical vision

Neuroscience work by Hubel and Wiesel (1950s) revealed key properties of early visual cortex that inform computational design.

- Neurons in primary visual cortex have localized receptive fields that respond to simple features like oriented edges.

- Visual processing is hierarchical: neurons at successive stages combine earlier feature detectors to represent increasingly complex patterns and object parts.

- These findings motivate hierarchical, layered computational architectures where local feature detectors feed into higher-level combinators.

- The neurophysiological evidence forms a conceptual bridge to multi-layer artificial neural networks used in modern computer vision.

Early computational vision research and its historical milestones

Foundational computational efforts in the 1960s and 1970s helped establish computer vision as an academic discipline.

- Early milestones include Larry Roberts’ 1963 PhD thesis on shape and MIT summer projects aimed at understanding visual perception.

- Those projects produced theoretical frameworks for surface and feature analysis and seeded long-term research trajectories despite optimistic short-term forecasts.

- The period shows how early algorithmic thinking evolved in parallel with theoretical and experimental neuroscience, laying groundwork for modern computer vision.

David Marr’s representational stages and the ill-posed nature of 3D recovery

David Marr’s framework formalizes visual processing into representational stages and a processing pipeline.

- Key stages: the primal sketch, the 2½D sketch, and the full 3D model—a progression from edge detection to volumetric representation.

- Recovering 3D structure from 2D retinal projections is fundamentally ill-posed: many different 3D scenes can produce similar 2D images, so additional constraints or multi-view data are required.

- Marr’s hierarchy frames vision problems as stages of representation and transformation rather than single-step mappings, guiding algorithm design and evaluation for tasks like depth estimation, multi-view reconstruction, and scene understanding.

Comparing language and vision; implications for generative models

The segment contrasts inherent differences between language and vision, and the modeling implications of those differences.

- Language is largely sequential and generated, which favors large-scale unsupervised generative modeling and sequence-based architectures.

- Vision corresponds to an external physical world governed by physics and material properties, requiring models that respect grounded physical consistency and multimodal constraints.

- These distinctions explain why certain generative algorithms excel in language domains while vision presents different empirical and theoretical challenges for generalization and generation.

- The comparison informs expectations about how readily modeling techniques transfer across modalities.

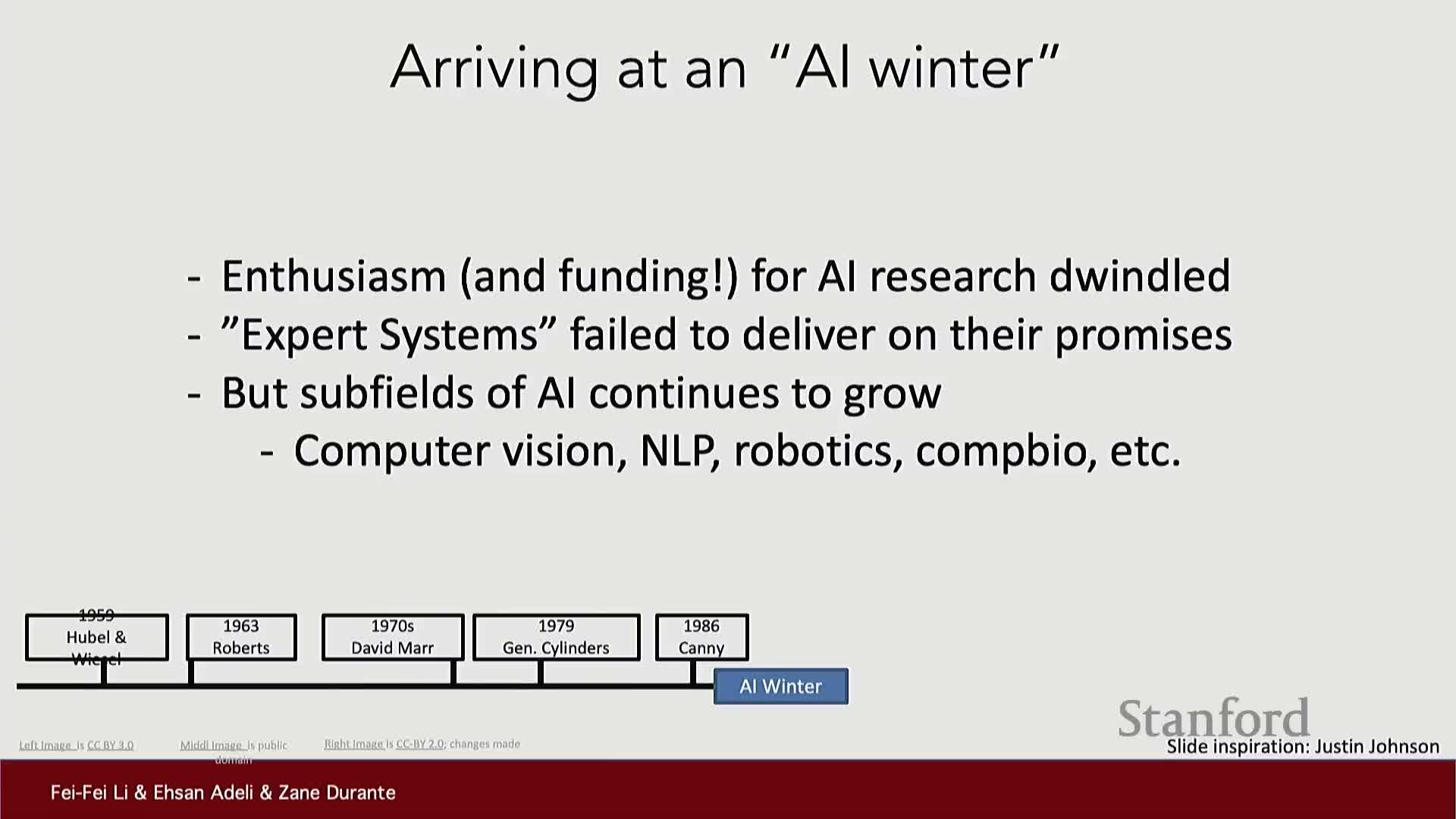

Progress through the 1970s–1980s, AI winter, and cognitive neuroscience guidance

Research in the 1970s and 1980s produced algorithmic advances but also faced setbacks in funding and expectations.

- Advances included generalized cylinder models and compositional representations for articulated objects.

- The era also saw an AI winter where funding and broad optimism receded.

- Cognitive neuroscience continued to provide experimental constraints, for instance showing that object recognition in natural scenes depends on global context.

- These interdisciplinary signals redirected computer vision toward naturalistic object recognition and informed feature and algorithm design that could handle real-world variability.

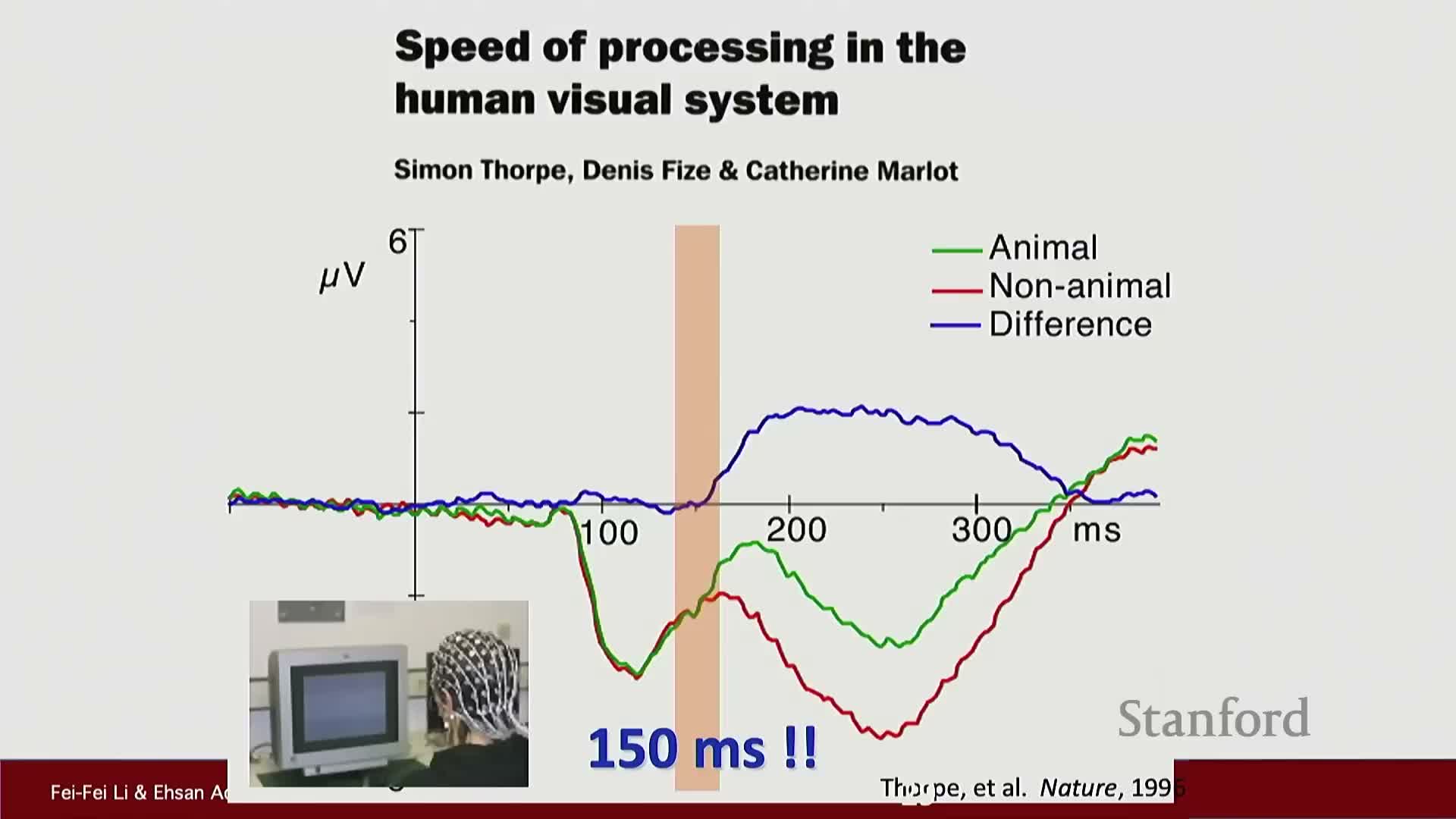

Psychophysical evidence of rapid and contextual visual processing

Psychophysical and neurophysiological studies place tight constraints on models of human vision.

- Humans detect and categorize objects extremely rapidly—often within 100–150 milliseconds of exposure—implying shallow, fast processing pipelines.

- Global image context influences detection and recognition; experiments comparing scrambled vs. intact scenes, video frame detection at 10 Hz, and EEG signatures quantify these effects.

- The existence of specialized cortical areas for faces, places, and bodies suggests task-specific circuitry can emerge for high-value categories.

- These empirical findings motivate computational architectures that are both fast and context-sensitive for practical object recognition.

Feature engineering, face detection, and the emergence of web-scale datasets

Research from the 1990s demonstrated how local features and practical algorithms enabled real products and created new data resources.

- Work on local features such as SIFT and robust face detection translated into products (e.g., auto-focus in digital cameras).

- The rise of the internet and digital photography produced large-scale image collections, enabling datasets like Pascal VOC and Caltech 101 as common benchmarks.

- These datasets shifted research from toy problems to realistic, varied images, making empirical evaluation and benchmarking central to progress.

- The availability of larger, labeled datasets revealed data as a critical axis alongside algorithms and compute.

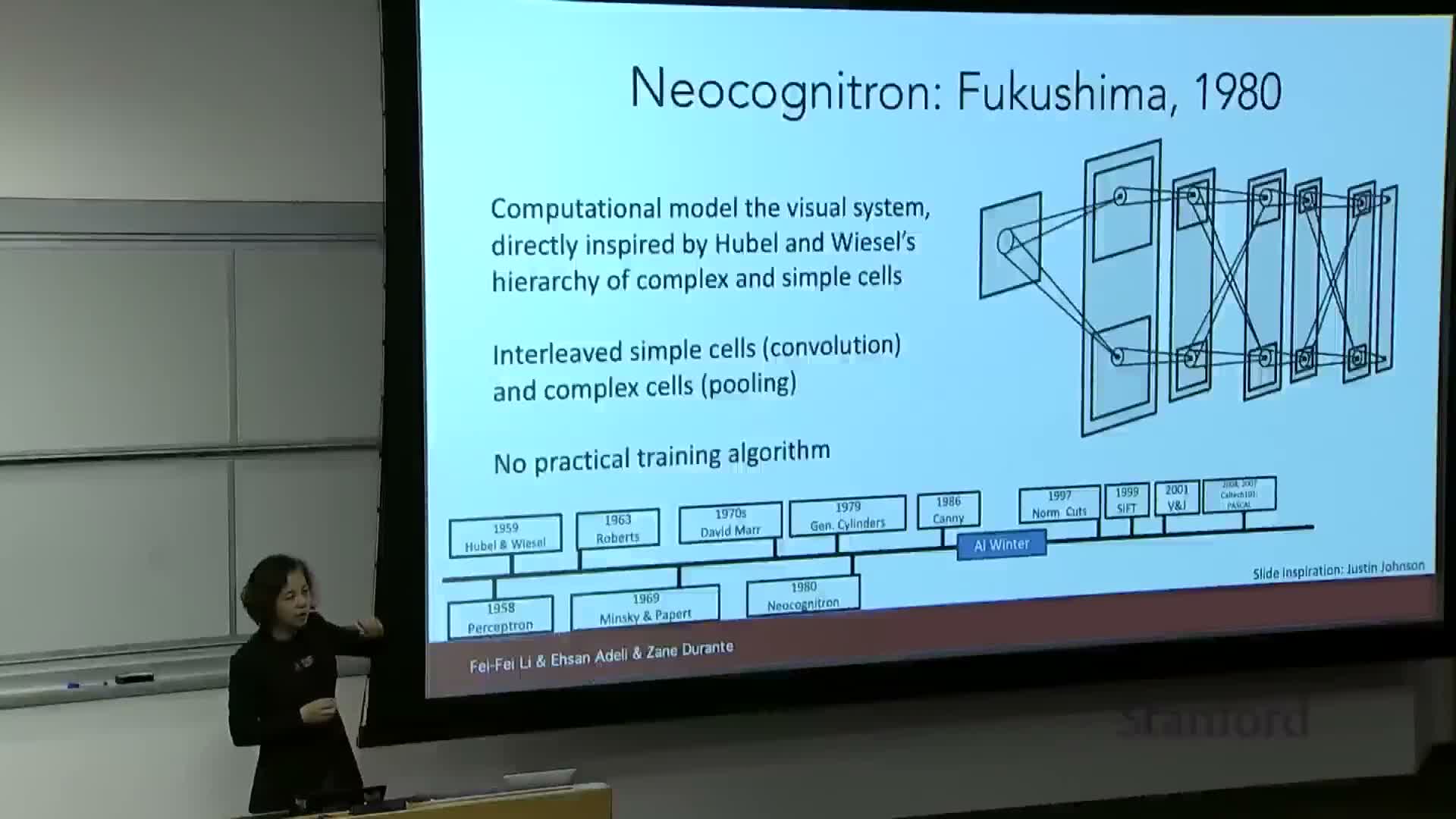

Historical roots of neural architectures and the neocognitron

Early neural architectures such as Fukushima’s neocognitron implemented multi-layer, convolution-like processing with hand-designed parameters.

- The neocognitron introduced layerwise specialization: early layers extract local features and later layers integrate them into complex representations.

- Parameters were engineered rather than learned, which limited scalability and required manual tuning.

- This architecture presaged modern convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and motivated research into automated learning procedures.

Backpropagation and its role in training neural networks

The development and formalization of backpropagation in the 1980s provided a principled method to train layered networks.

- Backpropagation uses the chain rule to propagate error gradients through layers and supports automatic differentiation of loss functions with respect to network parameters.

- It enables end-to-end training of multi-layer architectures from labeled data and transformed engineered hierarchical networks into learnable function approximators.

- The segment underscores backpropagation as a watershed moment that changed the trajectory of neural-network research.

Early applied convolutional networks and the data bottleneck

Applied convolutional systems demonstrated practical success but highlighted the need for large, diverse data.

- Early applied CNNs (e.g., LeCun’s systems) succeeded on constrained tasks like digit recognition and OCR, enabling deployments in postal systems and banking.

- Progress on general object recognition lagged due to the lack of sufficiently large and diverse labeled datasets required by high-capacity models.

- The segment emphasizes that model capacity and algorithmic expressivity require commensurate data to generalize and avoid overfitting, motivating systematic dataset collection and curation efforts.

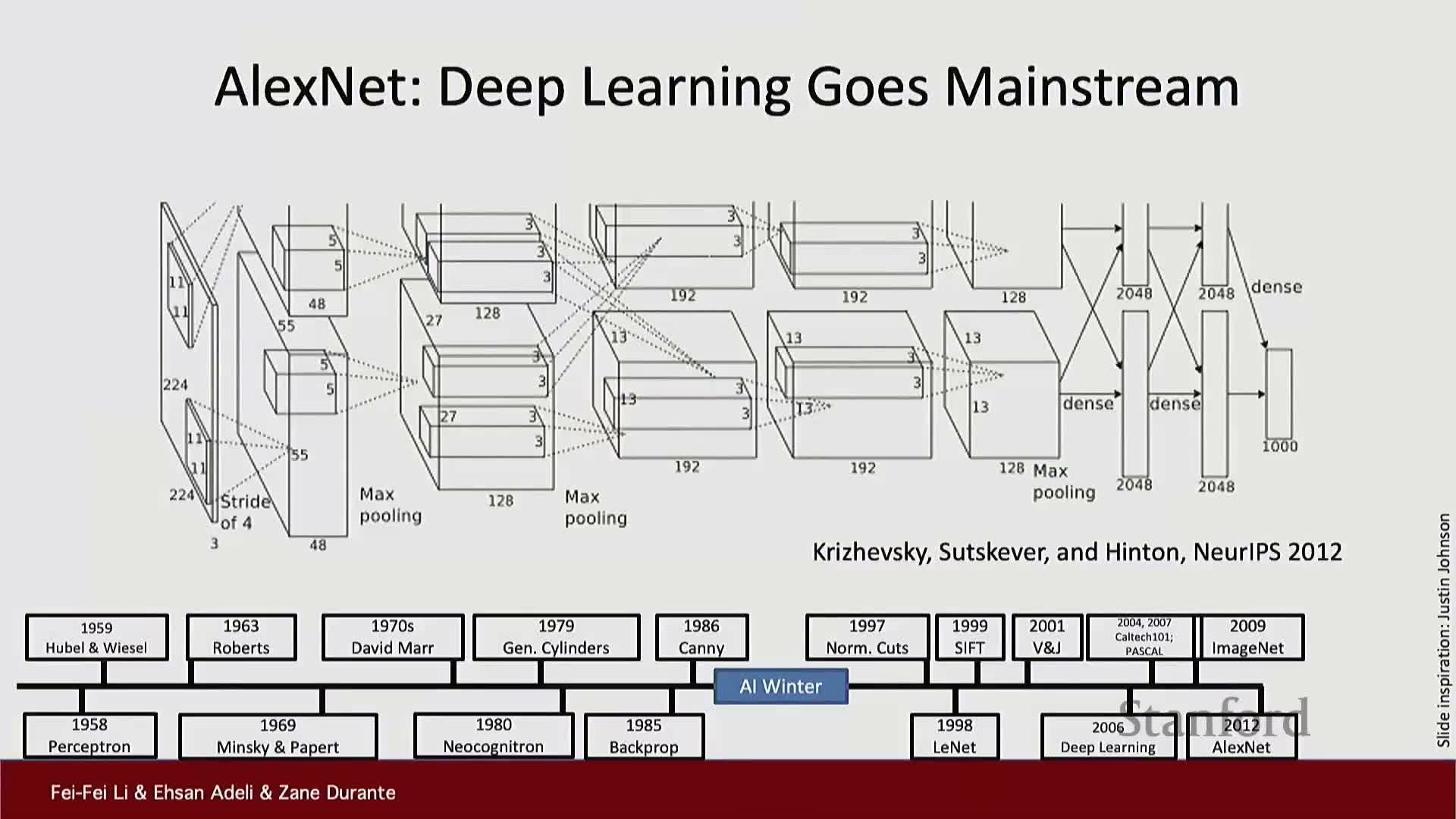

ImageNet, large-scale benchmarks, and the 2012 inflection point

The creation of ImageNet enabled large-scale supervised training and rigorous benchmarking for recognition tasks.

- ImageNet provided millions of labeled images across thousands of categories and supported the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge.

- It highlighted the importance of data scale and taxonomy design, and exposed performance gaps between algorithms and humans on realistic tasks.

- The 2012 entry AlexNet, a deep convolutional network trained with backpropagation on ImageNet-scale data, dramatically reduced top-5 error and is widely recognized as the practical inflection point for the modern deep learning era.

- This event catalyzed rapid adoption of deep convolutional models in computer vision and beyond.

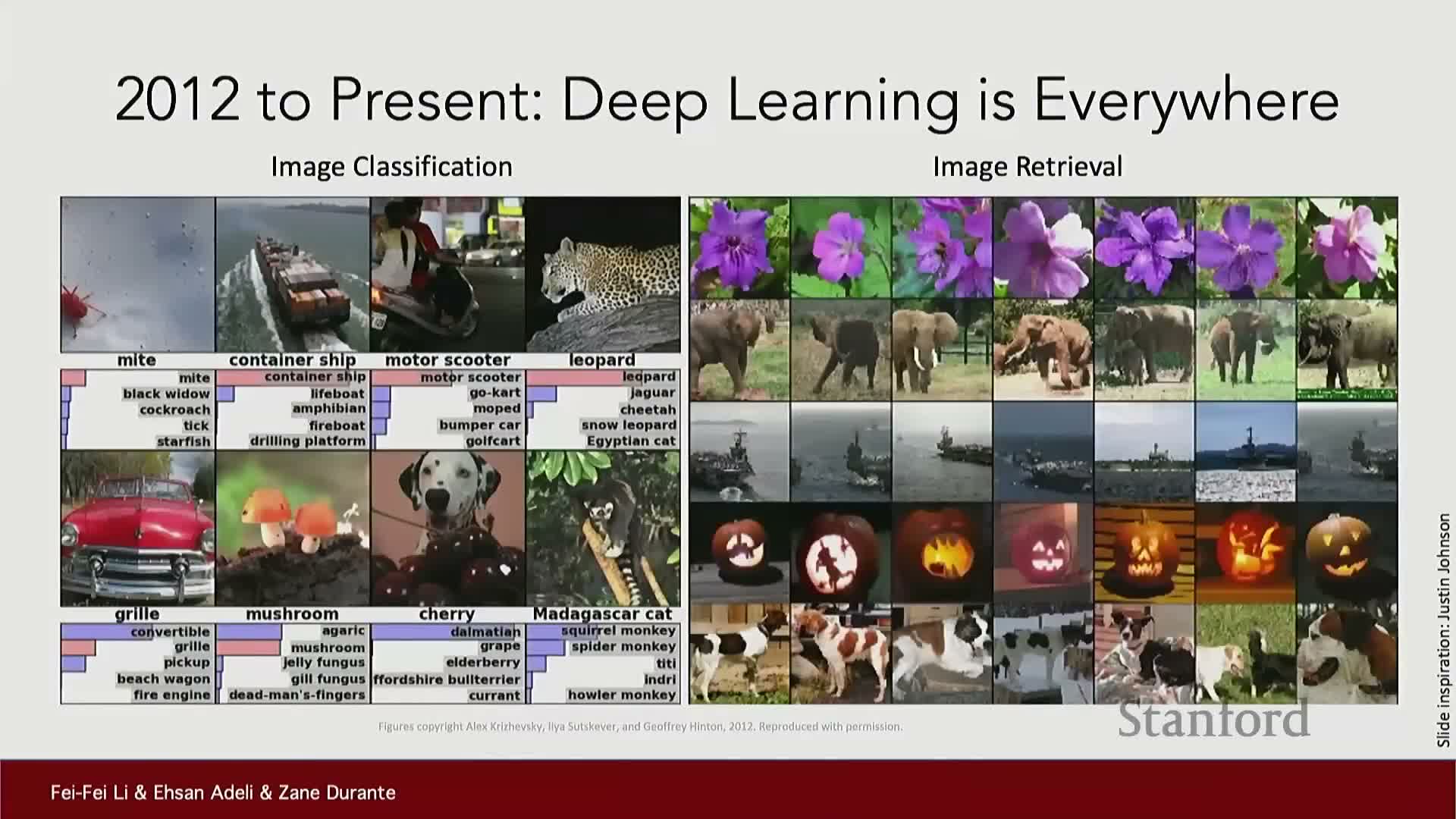

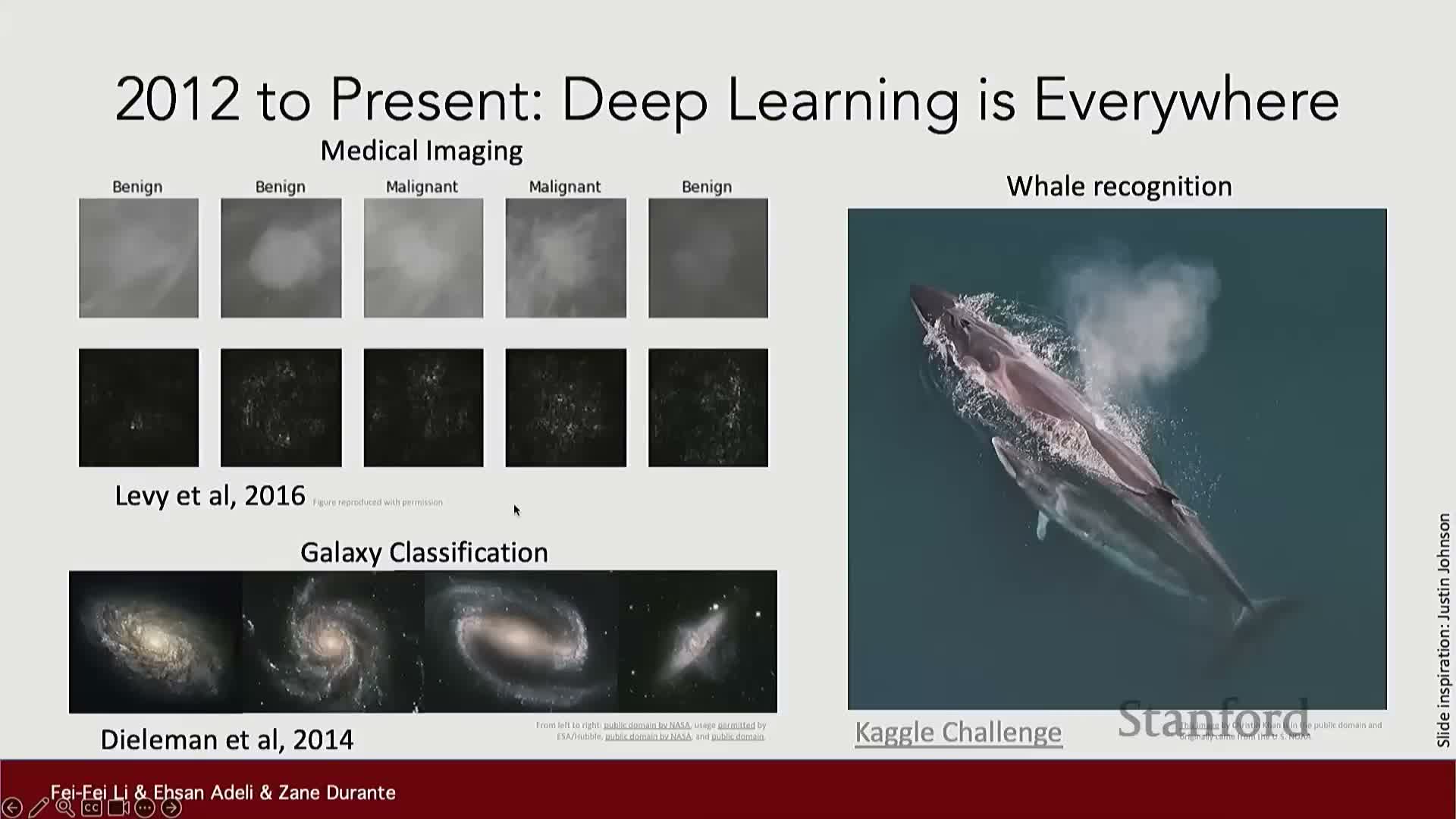

Post-ImageNet advances across vision tasks and model families

After the ImageNet breakthrough, research rapidly diversified across many vision tasks.

- Expansions included multi-object detection, instance segmentation, image retrieval, and video understanding.

- The field moved beyond single-label classification toward structured prediction and dense labeling problems that require localization and per-pixel inference.

- Success relied on architectural innovations, improved loss functions, and large-scale supervised training, demonstrating deep networks’ applicability to complex visual reasoning.

- The segment frames these developments as an expanding ecosystem of applications and technical challenges.

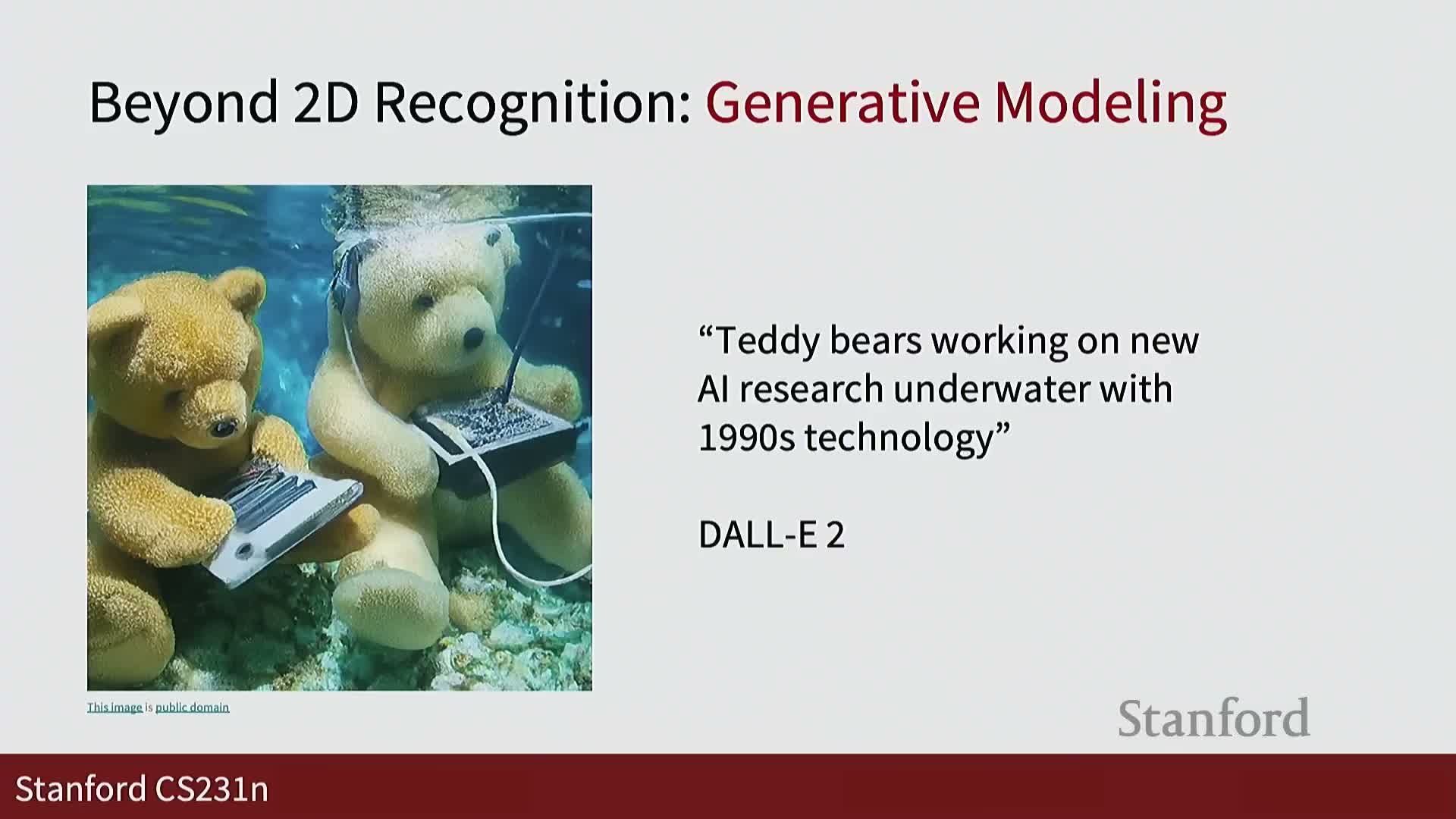

Generative models, image captioning, and the rise of vision generative AI

Generative modeling extended visual intelligence from recognition to synthesis and creative applications.

- Early milestones include image captioning and style-transfer systems.

- Generative approaches such as GANs and diffusion models learn image distributions and can be conditioned on text to produce controllable outputs.

- Modern tools (e.g., DALL·E, Midjourney) combine visual understanding with creative synthesis for content creation, data augmentation, and multimodal interaction.

- These advances broaden visual intelligence to generation, creativity, and multimodal conditioning.

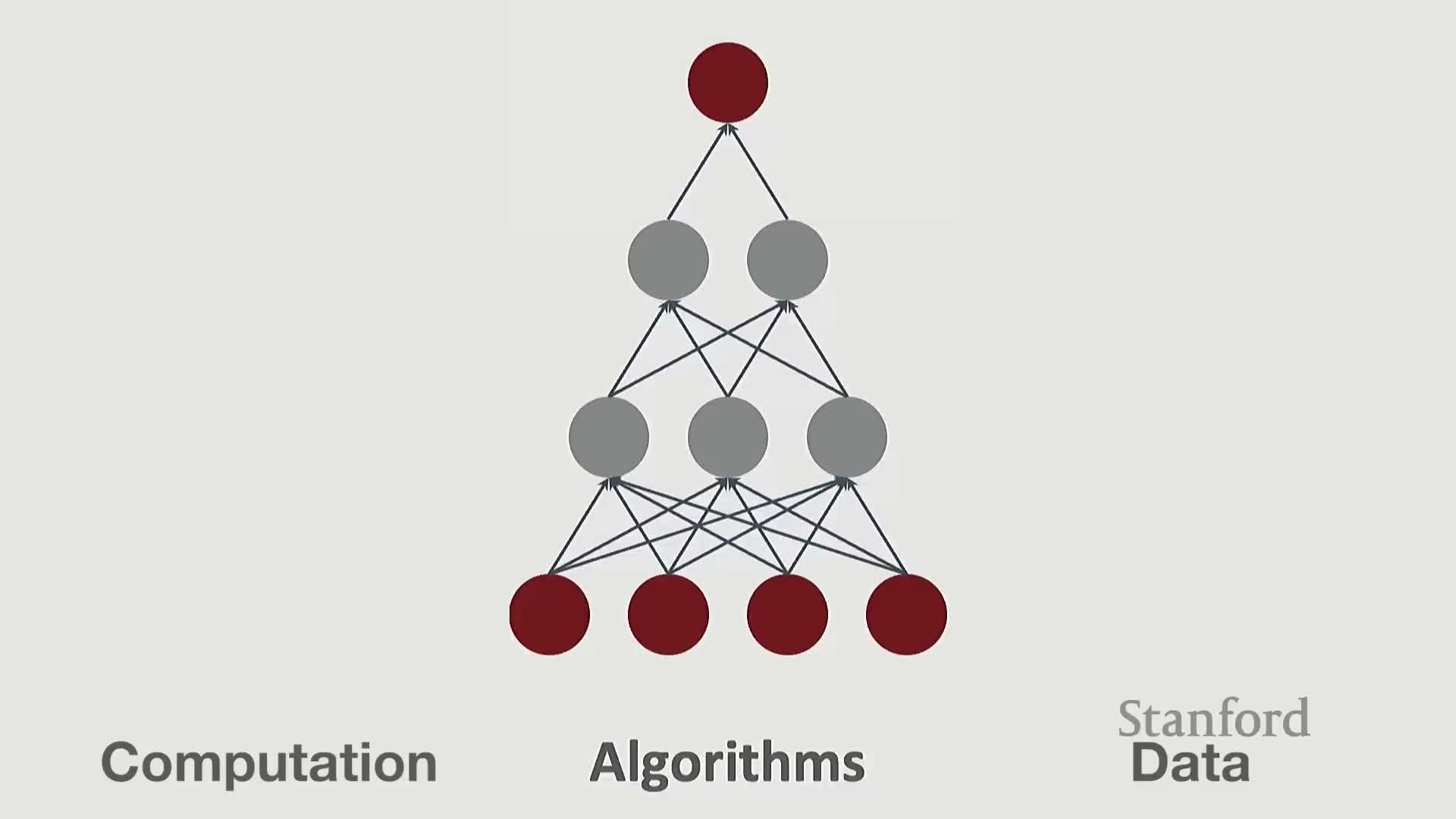

Compute and hardware acceleration driving model scaling

Exponential improvements in compute efficiency—GPUs and specialized accelerators—have been central to scaling vision models.

- Reduced cost per FLOP and better hardware enable training and deployment of much larger models.

- The interaction among compute, data, and algorithms produces multiplicative progress in model capacity and capability.

- Hardware trends, conference growth, and startup activity are indicators of an accelerating research and deployment ecosystem.

- This observation grounds practical considerations for researchers and engineers designing large-scale vision systems.

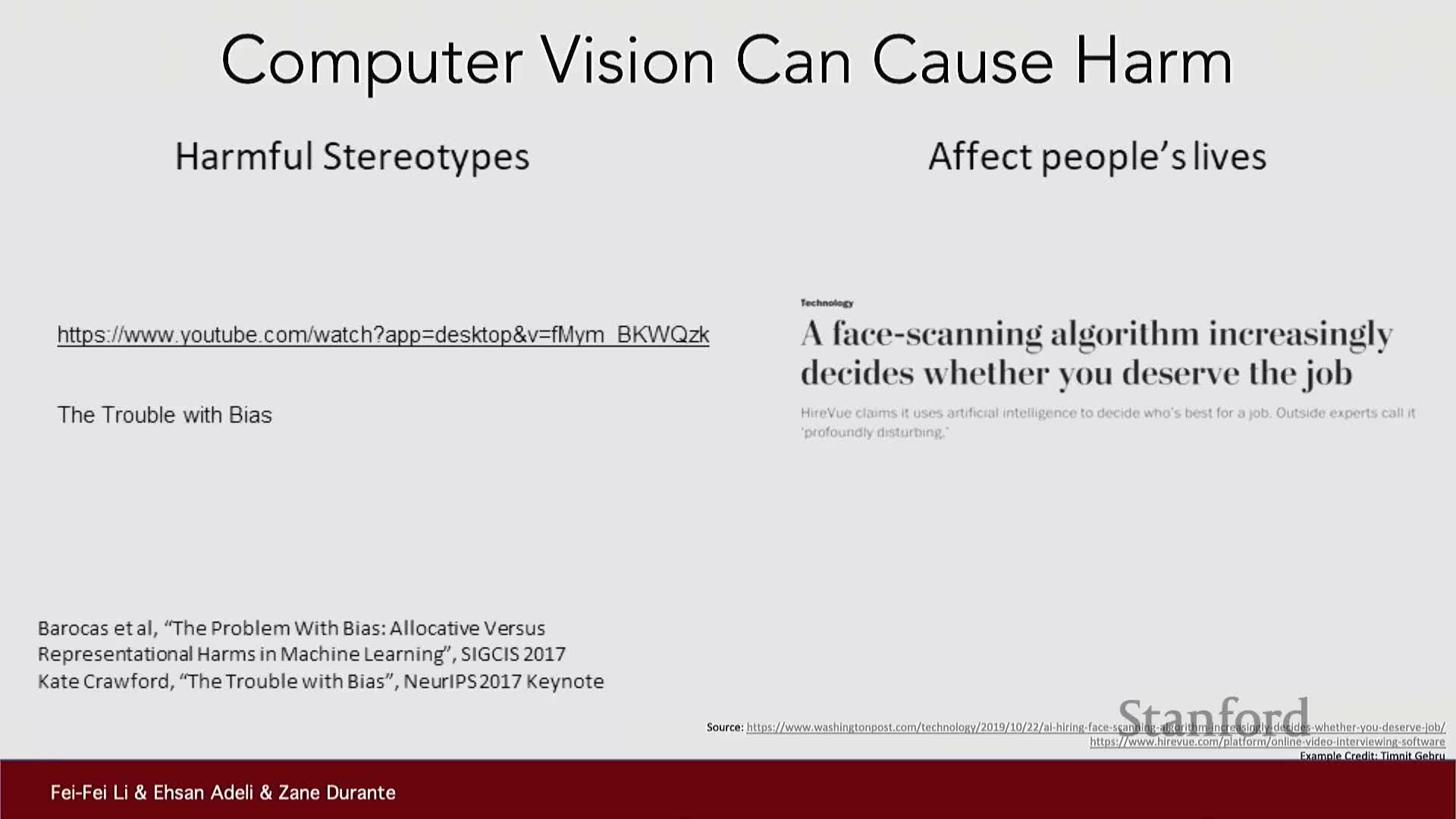

Ethical considerations, biases, and human-centered applications

The segment emphasizes that visual AI systems inherit biases from training data and can have major societal impacts.

- Deployed systems affect human lives in domains such as hiring, lending, and law enforcement, raising concerns about fairness and accountability.

- There are beneficial applications—medical imaging for diagnosis and care for aging populations—alongside potential harms from consequential automated decisions.

- Addressing these issues requires interdisciplinary engagement from the humanities, law, and policy practitioners in addition to engineers.

-

Human-centered design and ethical evaluation are presented as core responsibilities in vision system development.

Course goals and high-level topic categorization

The course is organized around four broad themes and clear learning objectives.

- Four themes: deep learning basics, perception and understanding tasks, large-scale training, and generative/interactive visual intelligence.

- Learning objectives include formalizing vision tasks, developing and training models for images and video, and understanding research trajectories and societal implications.

- The curriculum balances foundational material (model architectures, optimization) with advanced topics (self-supervised learning, large-model training).

- This structure sets expectations for theoretical rigor and practical system-building via assignments and projects.

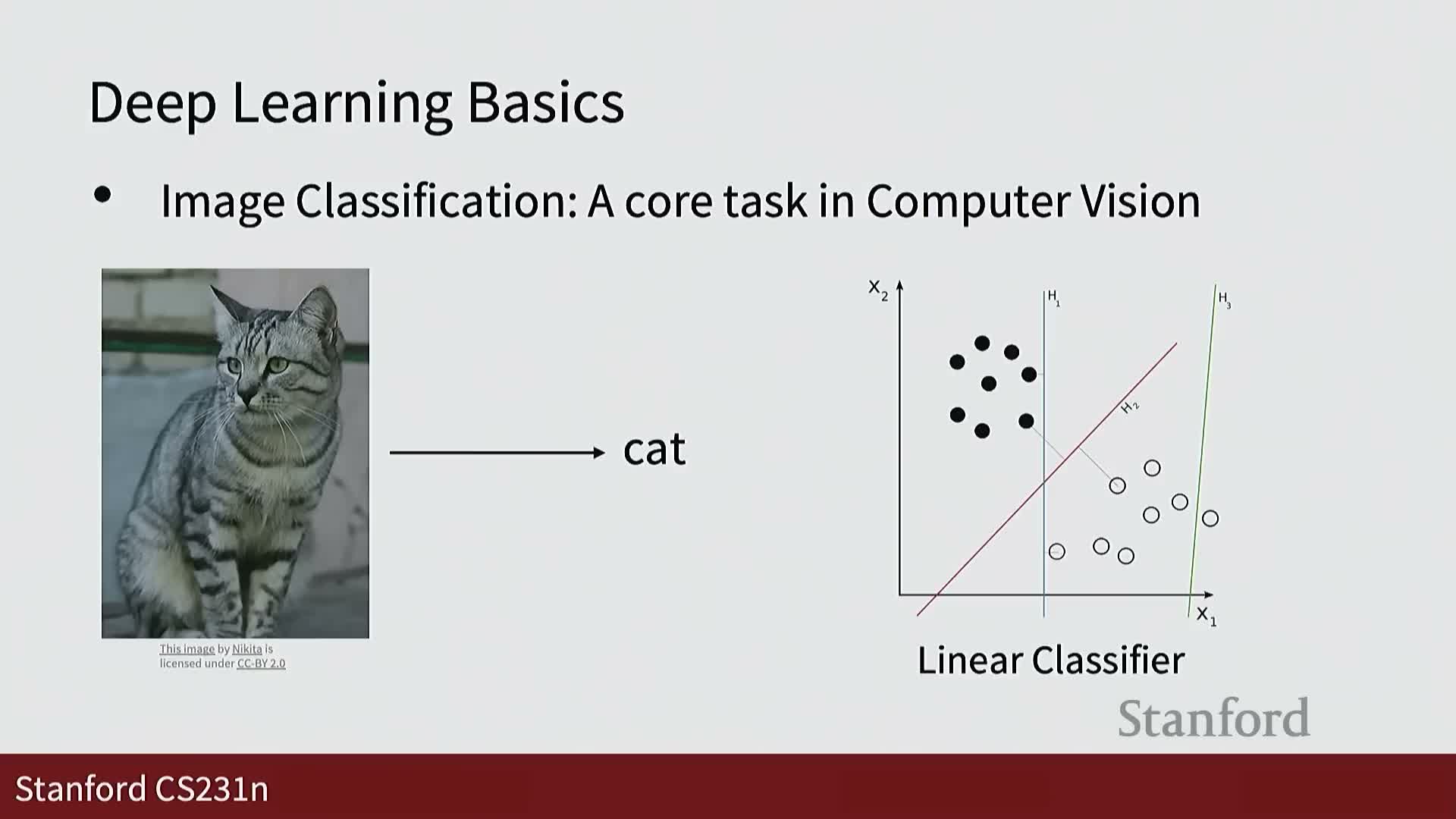

Image classification as a foundational computer vision task and linear baselines

Image classification is defined as the canonical task of predicting a single semantic label for an entire image.

- Serves as a foundational benchmark for model development.

- Linear classifiers are introduced as simple baselines that separate classes using hyperplanes in feature space—offering interpretability but limited capacity when data are not linearly separable.

- The segment motivates moving beyond linear models to nonlinear architectures that capture complex feature interactions, and foreshadows issues like overfitting, regularization, and optimization that are critical to model performance.

Neural networks and stacking layers to model nonlinear functions

Neural networks are presented as compositional models that stack multiple layers of parameterized operations to approximate complex nonlinear functions.

- Deep architectures enable hierarchical feature extraction: successive layers transform raw inputs into increasingly abstract representations.

- The lecture outlines practical concerns: training procedures, debugging, and methods to improve generalization.

- These nuts-and-bolts topics justify studying convolutional networks, recurrent networks, and attention-based architectures throughout the course.

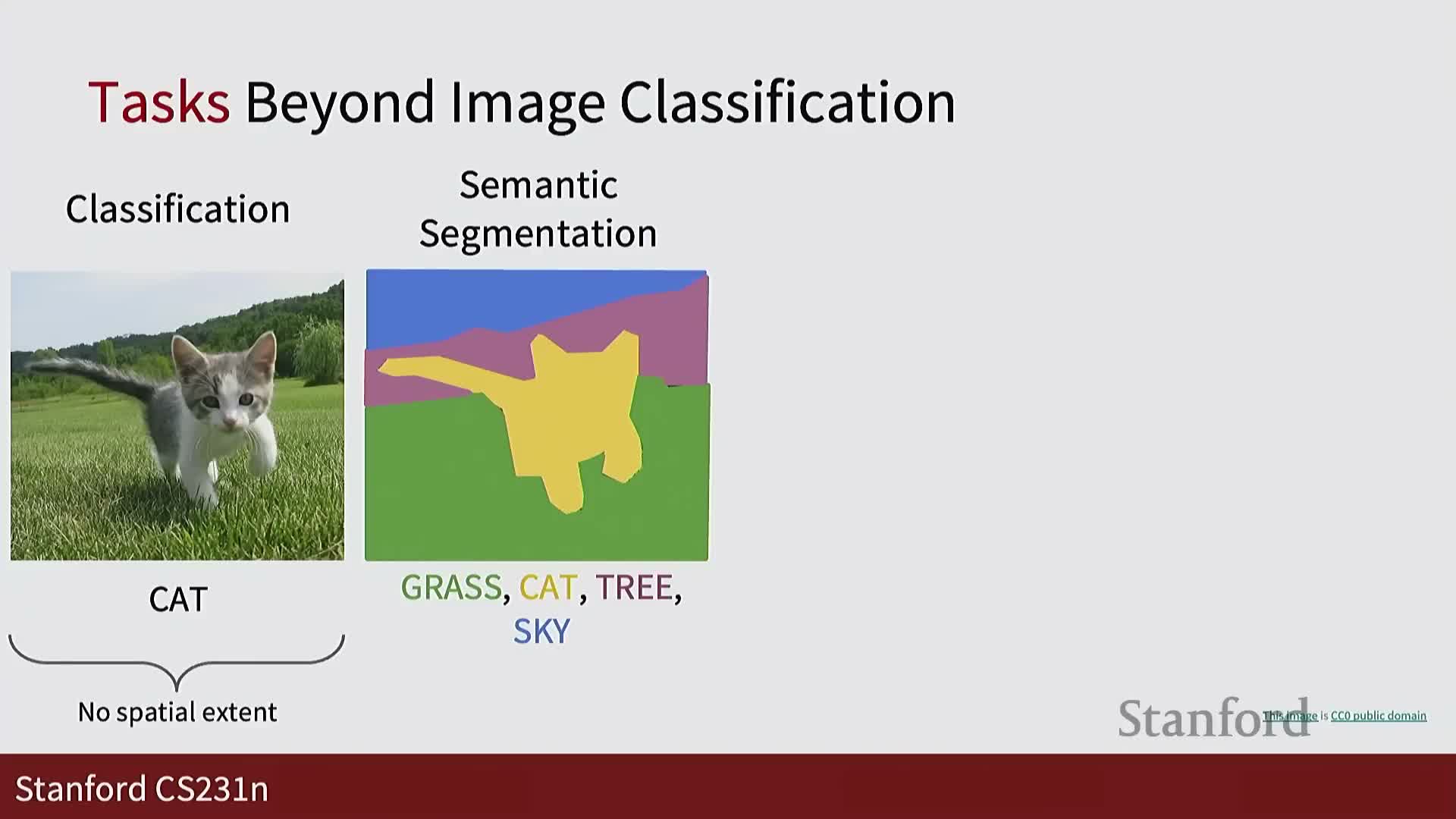

Defining vision tasks: semantic segmentation, object detection, instance segmentation

The course distinguishes several core vision tasks and their requirements.

- Semantic segmentation: assign a class label to every pixel without distinguishing instances.

- Object detection: localize objects via bounding boxes and class labels.

- Instance segmentation: provide per-instance masks, combining detection and segmentation.

- Each task requires different model outputs, losses, and evaluation metrics, and pushes models to capture spatial, contextual, and object-level structure.

- Understanding these formal definitions and evaluation protocols is necessary for architecture design, dataset annotation, and assessing real-world performance trade-offs.

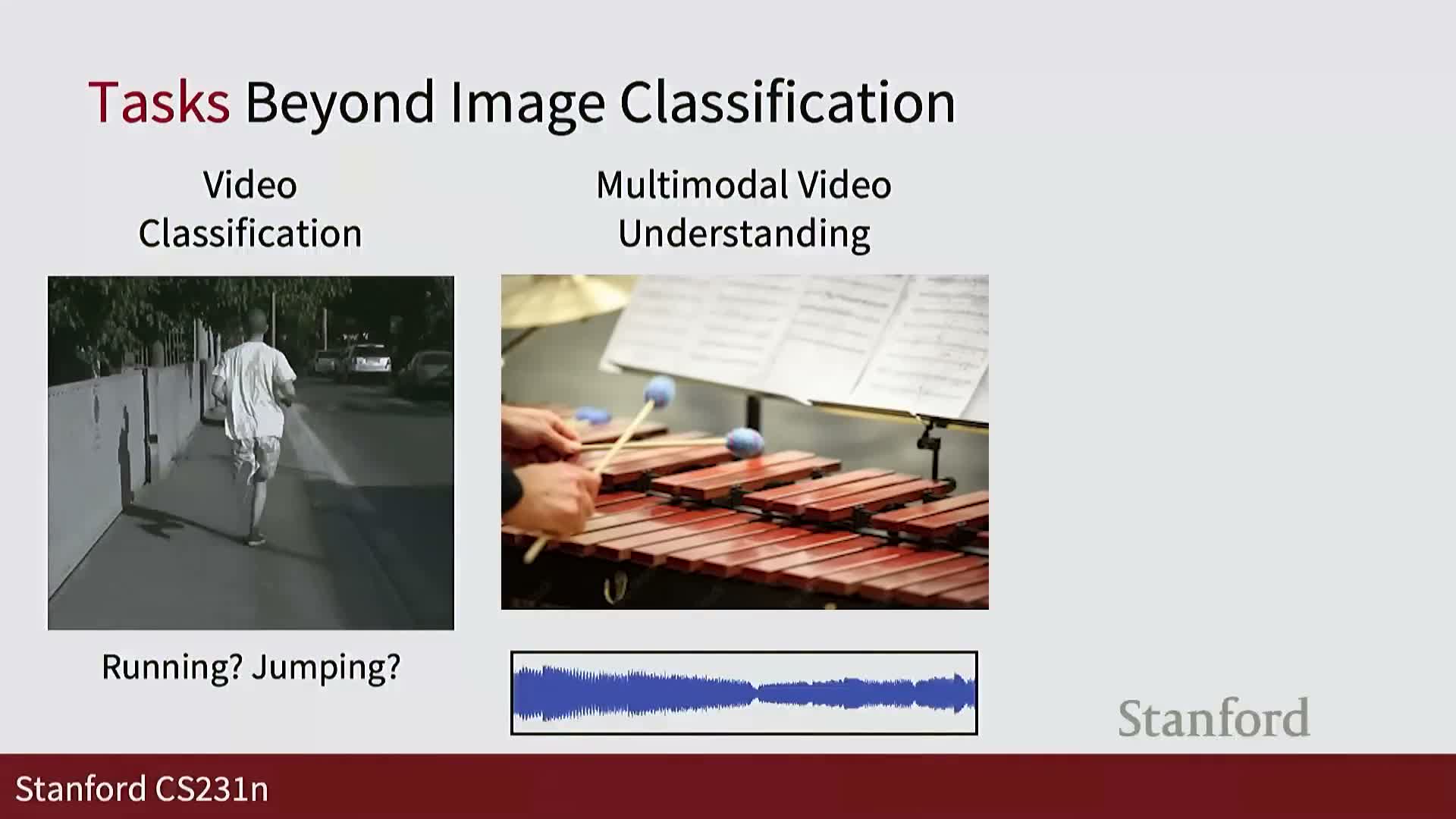

Temporal and multimodal vision tasks and model interpretability

Video understanding extends image modeling to temporal dynamics and multimodal signals.

- Tasks include activity recognition and modeling spatiotemporal patterns across frames.

- Multimodal video understanding integrates visual and audio streams, motivating fused representations and cross-modal alignment.

- The segment highlights interpretability techniques—attention maps and saliency visualizations—that reveal which input regions influence model decisions and aid debugging and trustworthiness.

- These topics extend static image modeling to richer, temporally and semantically grounded problems.

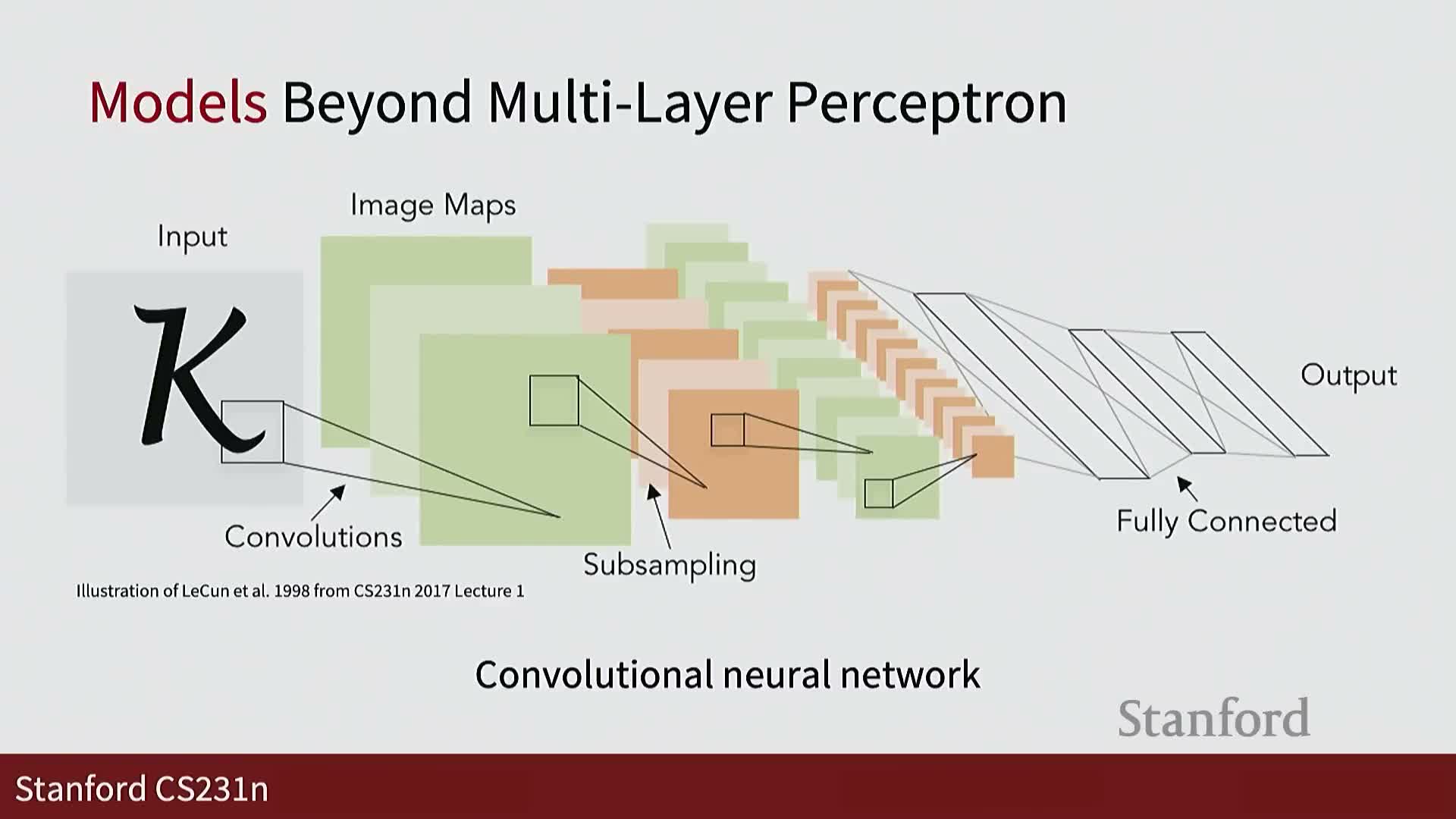

Core model families: convolutional networks, recurrent networks, and transformers

The lecture introduces major model families and their operations for different data structures.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): primary architecture for spatially structured image data; operations include convolution, pooling, sampling, and fully connected layers.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs): appropriate for sequential data processing, including temporal sequences in video.

- Transformers and attention-based architectures: modern alternatives that provide scalable context aggregation and are central to vision and multimodal modeling.

- The segment prepares students to study implementation details, inductive biases, and trade-offs across these model families.

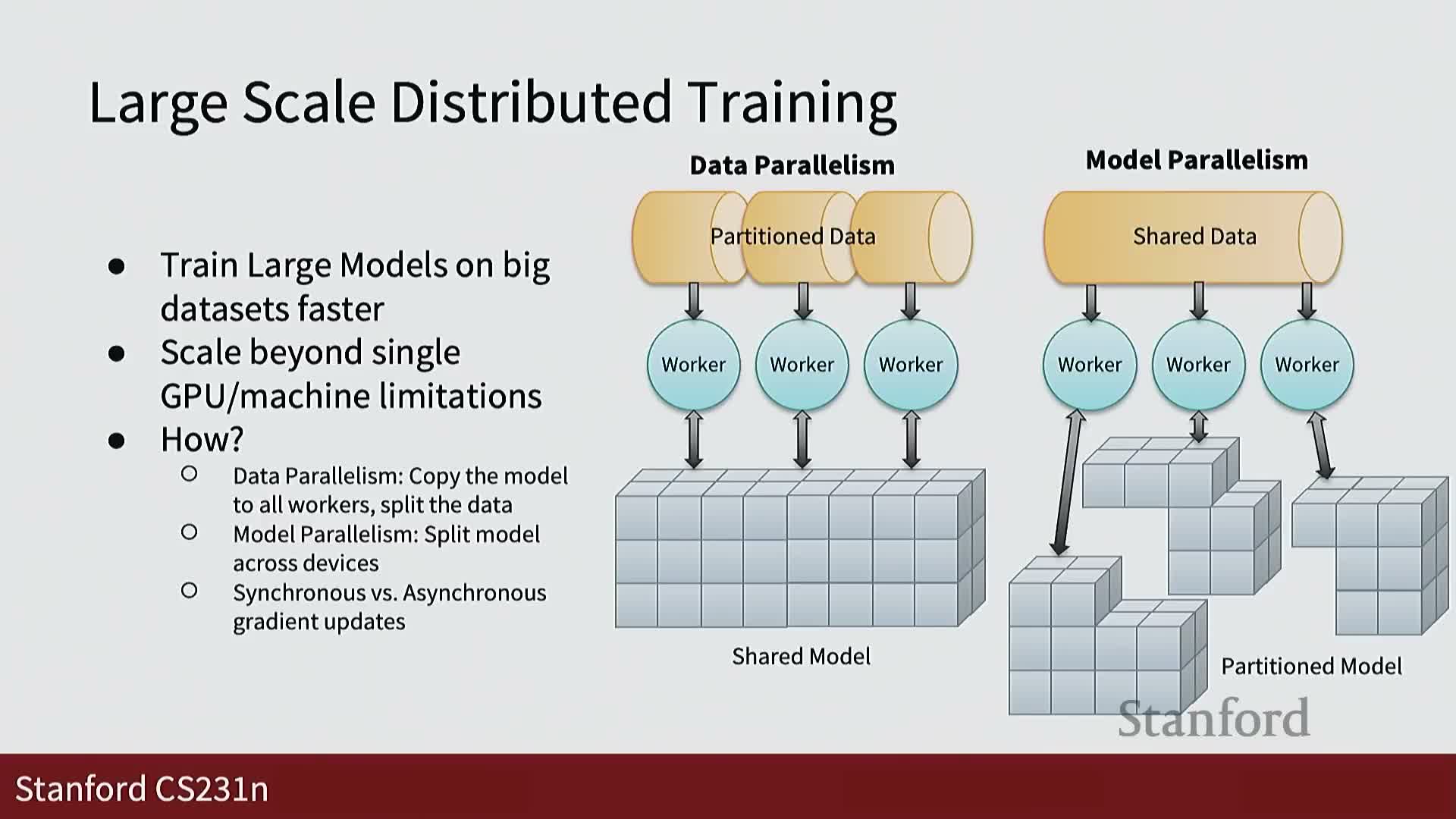

Large-scale distributed training and system-level considerations

Training very large vision models requires distributed strategies and careful system design.

- Parallelism strategies: data parallelism and model parallelism to partition computation across devices and nodes.

- Engineering challenges include synchronization, communication overhead, optimizer scalability, and fault tolerance.

- System-level design choices—batch size, learning rate schedules, checkpointing, and gradient aggregation—substantially affect convergence and final performance.

- Understanding these techniques is necessary for reproducing large-model results and designing resource-efficient training pipelines.

Self-supervised and generative modeling approaches

Self-supervised learning and generative models broaden how models learn from data.

- Self-supervised learning obtains supervisory signals from structure in unlabeled data to learn representations useful for downstream tasks, enabling use of vast image collections.

- Generative models (style transfer, diffusion-based generators) synthesize new images by modeling data distributions or reversing noise processes.

- These approaches expand visual intelligence beyond recognition to content creation, representation learning, and controllable generation.

- Hands-on assignments will provide practical implementation experience, reflecting the central role of these methods in recent breakthroughs.

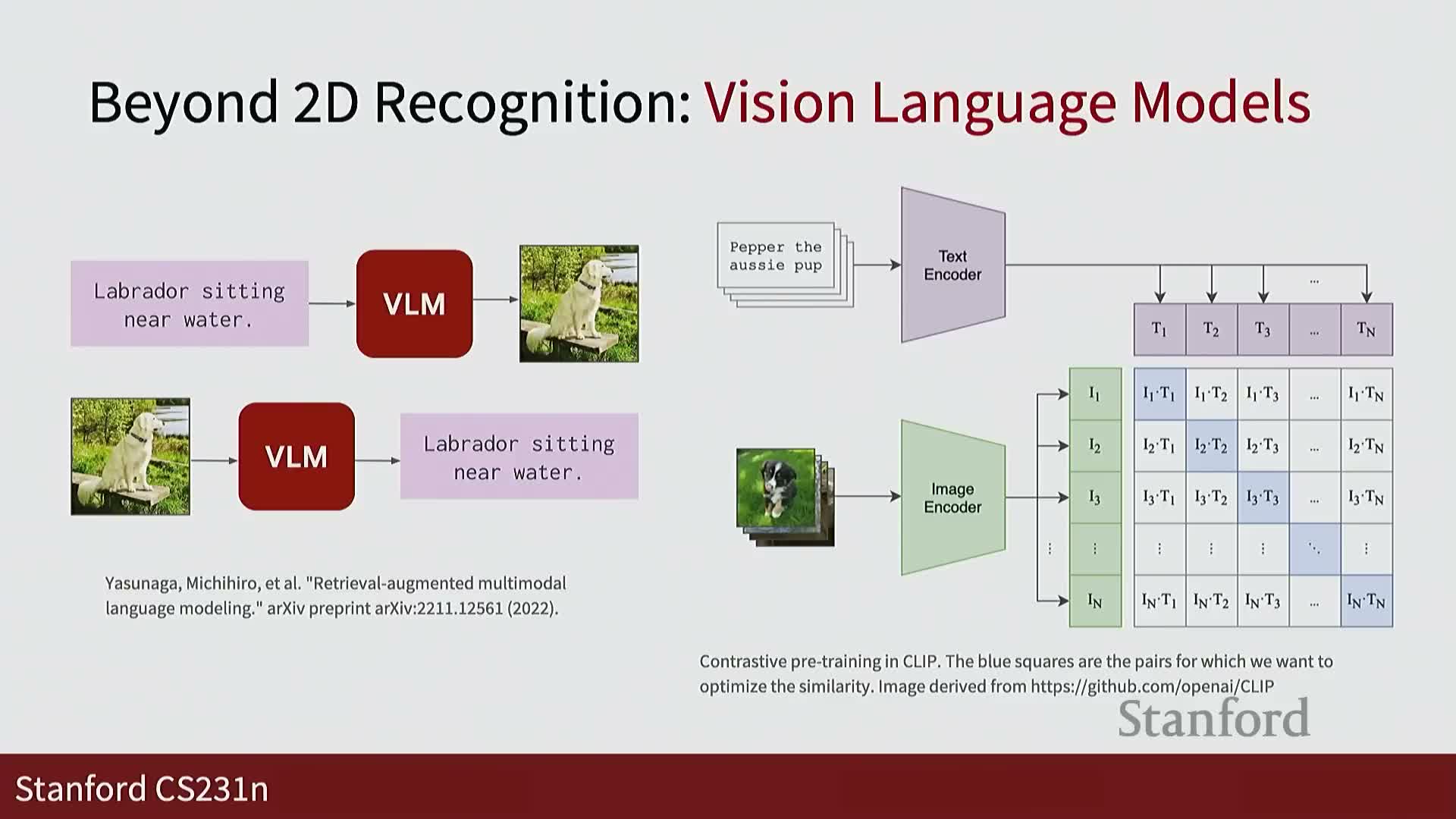

Vision-language models and cross-modal representations

Vision-language models learn shared representation spaces that align images and text for cross-modal tasks.

- Enable tasks such as image retrieval, captioning, and visual question answering by mapping visual and textual inputs into compatible embeddings.

- Support cross-modal search and conditional generation, where language queries control visual outputs.

- Key technical elements include alignment objectives, contrastive losses, and multimodal pretraining strategies necessary to design effective vision-language systems.

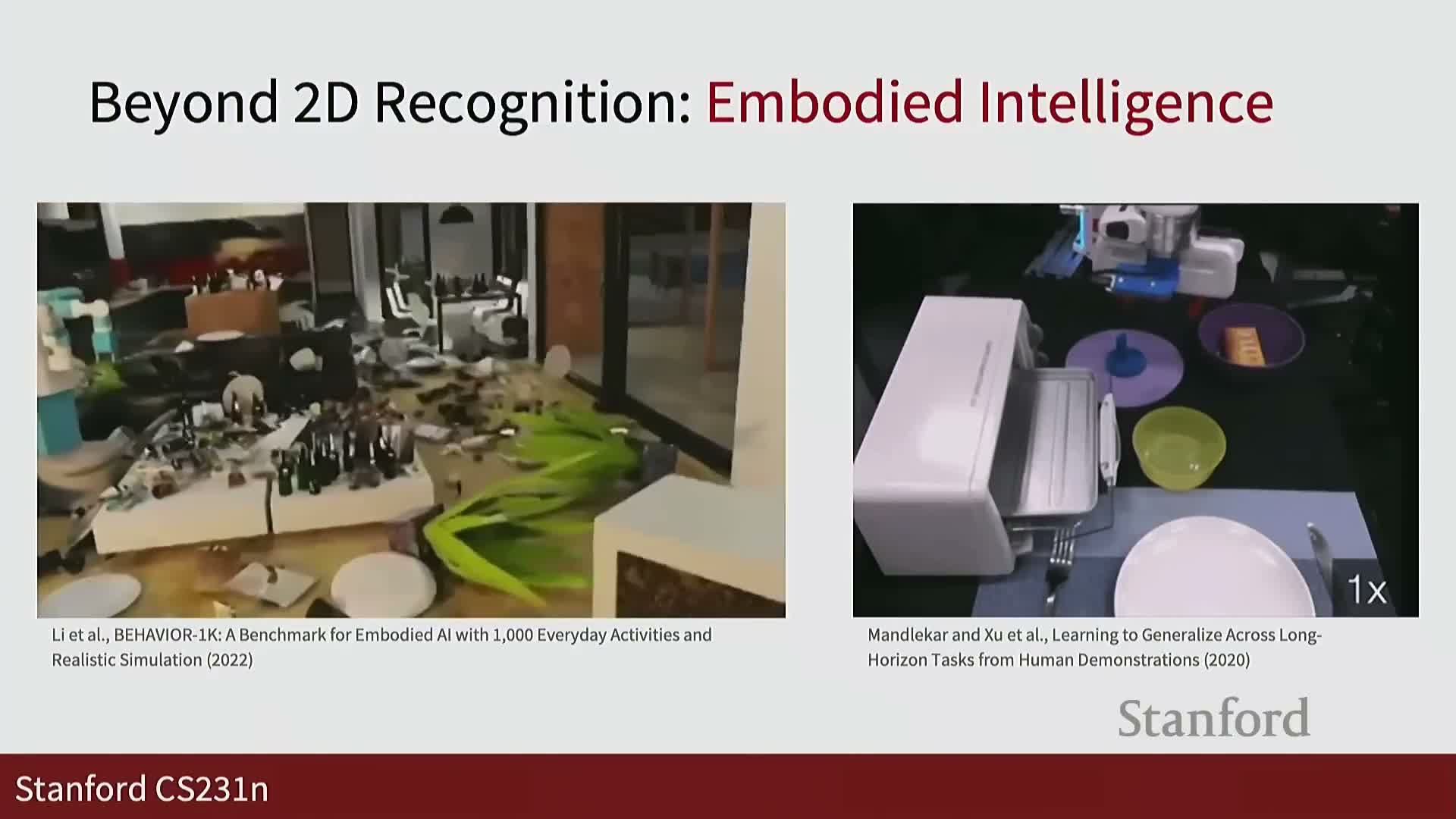

3D vision and embodied agents for grounded understanding

Modern vision modeling extends to reconstructing and generating 3D representations and to embodied perception-action systems.

- 3D representations use voxel grids, meshes, and implicit functions for shape completion and single-view 3D inference.

- These capabilities provide geometrically grounded understanding essential for robotics, AR/VR, and physically interactive agents.

- Embodied agents perceive, plan, and act in the world, requiring integrated perception–planning pipelines and generalization from human demonstrations.

- These topics connect perception to action and highlight research directions in spatial reasoning and physically grounded intelligence.

Awards, learning objectives, and next lecture preview

The course contextualizes recent field milestones and reiterates student outcomes.

- Cites major awards recognizing foundational contributions to deep neural networks and situates current learning objectives: formalizing vision tasks, developing and training models, and understanding field trajectories.

- Students will learn to build models from scratch, study modern trends (large-scale training, human-centered AI), and gain practical skills through assignments and projects.

- The segment previews the next lecture topic—image classification and linear classifiers—establishing the immediate technical starting point for the course and framing upcoming lectures and assessments.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: