Stanford CS231N | Spring 2025 | Lecture 12- Self-Supervised Learning

- Motivation for self-supervised learning and the role of learned image representations

- Definition of self-supervised learning: pretext tasks, encoder and decoder, and transfer to downstream tasks

- Catalog of common transformation-based pretext tasks

- Evaluation dimensions for self-supervised representations

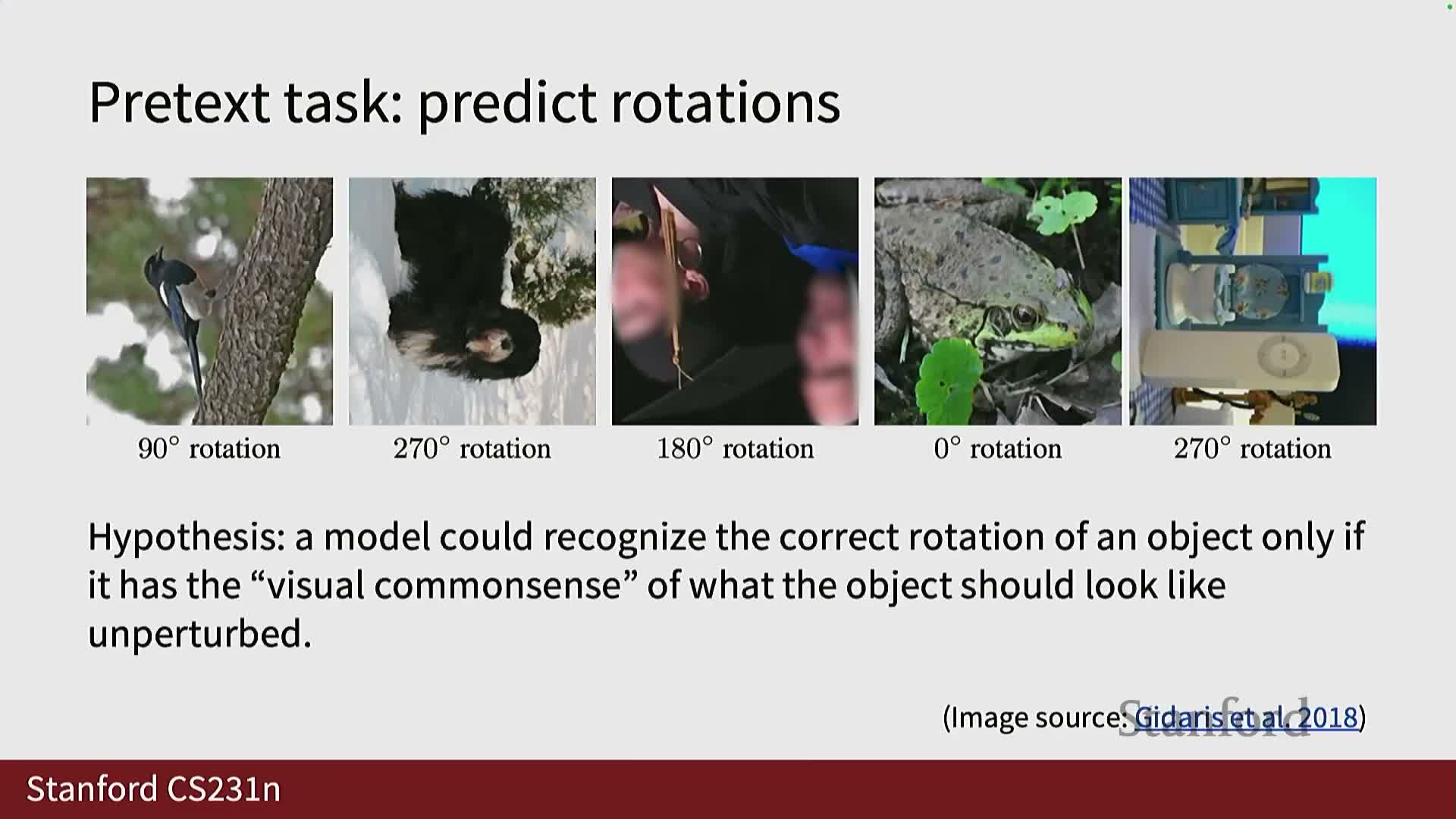

- Rotation-prediction as a pretext task and empirical effects

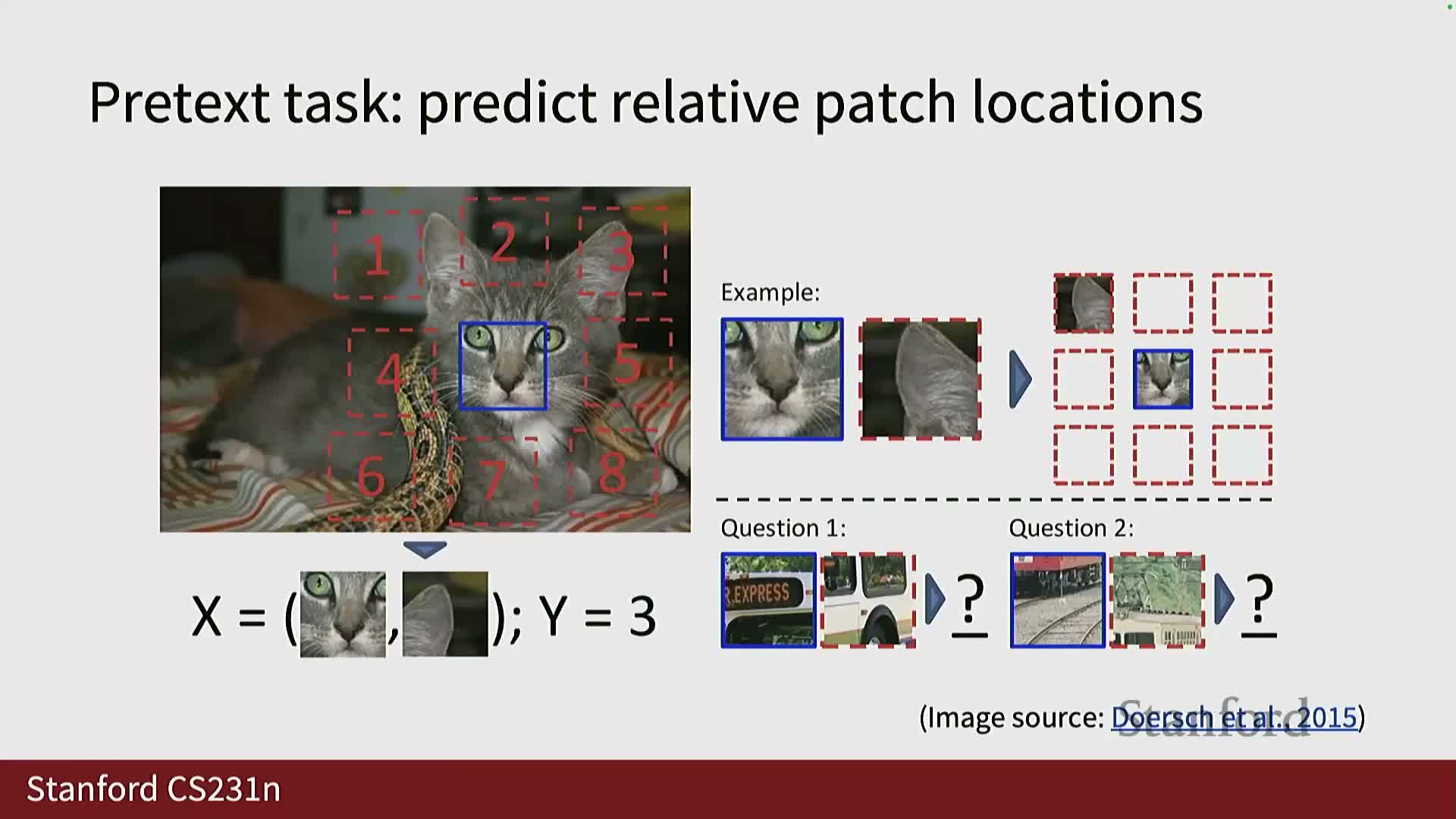

- Patch-based pretext tasks: relative patch location and jigsaw permutation

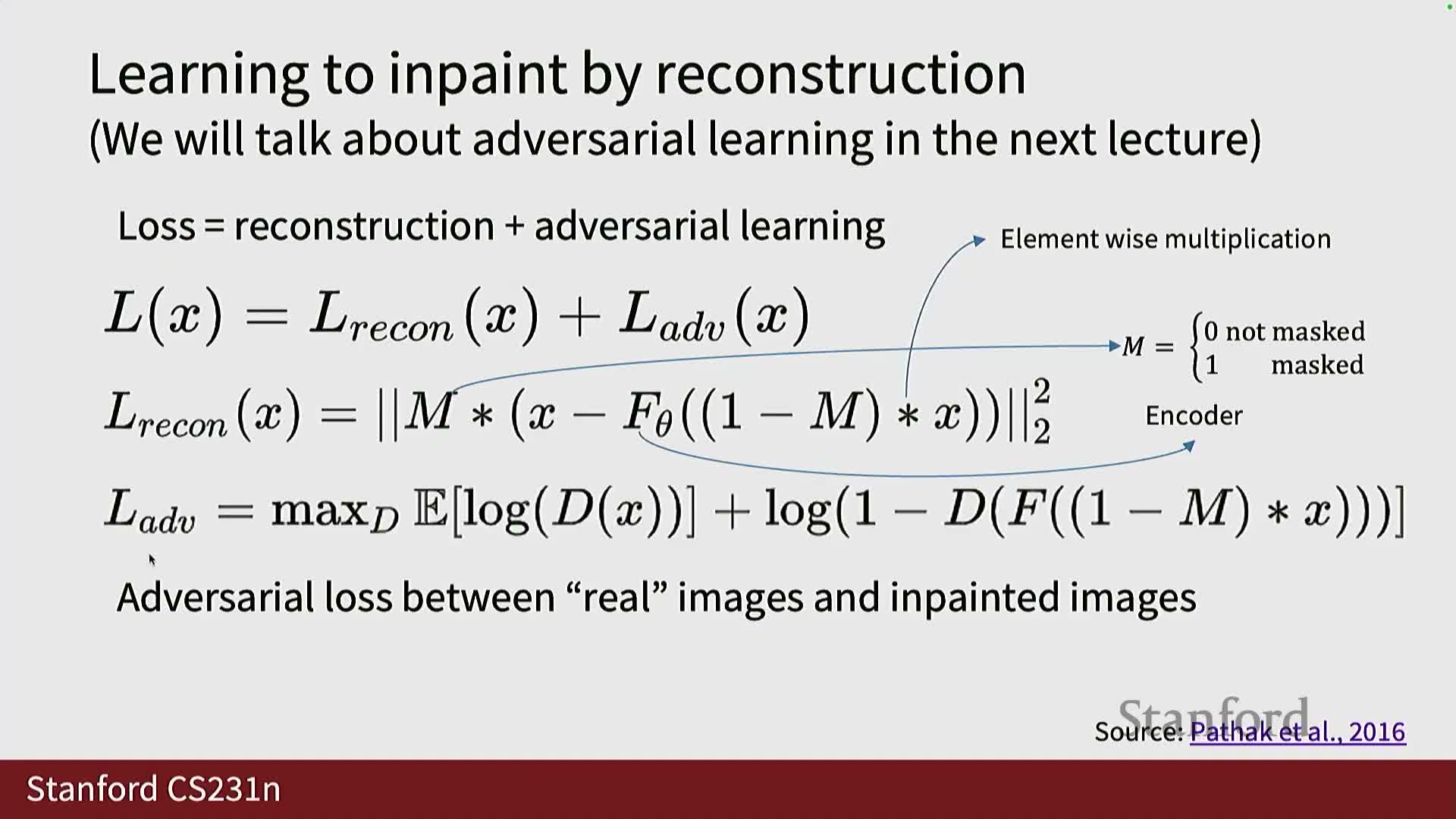

- Inpainting (masking) pretext tasks and reconstruction loss design

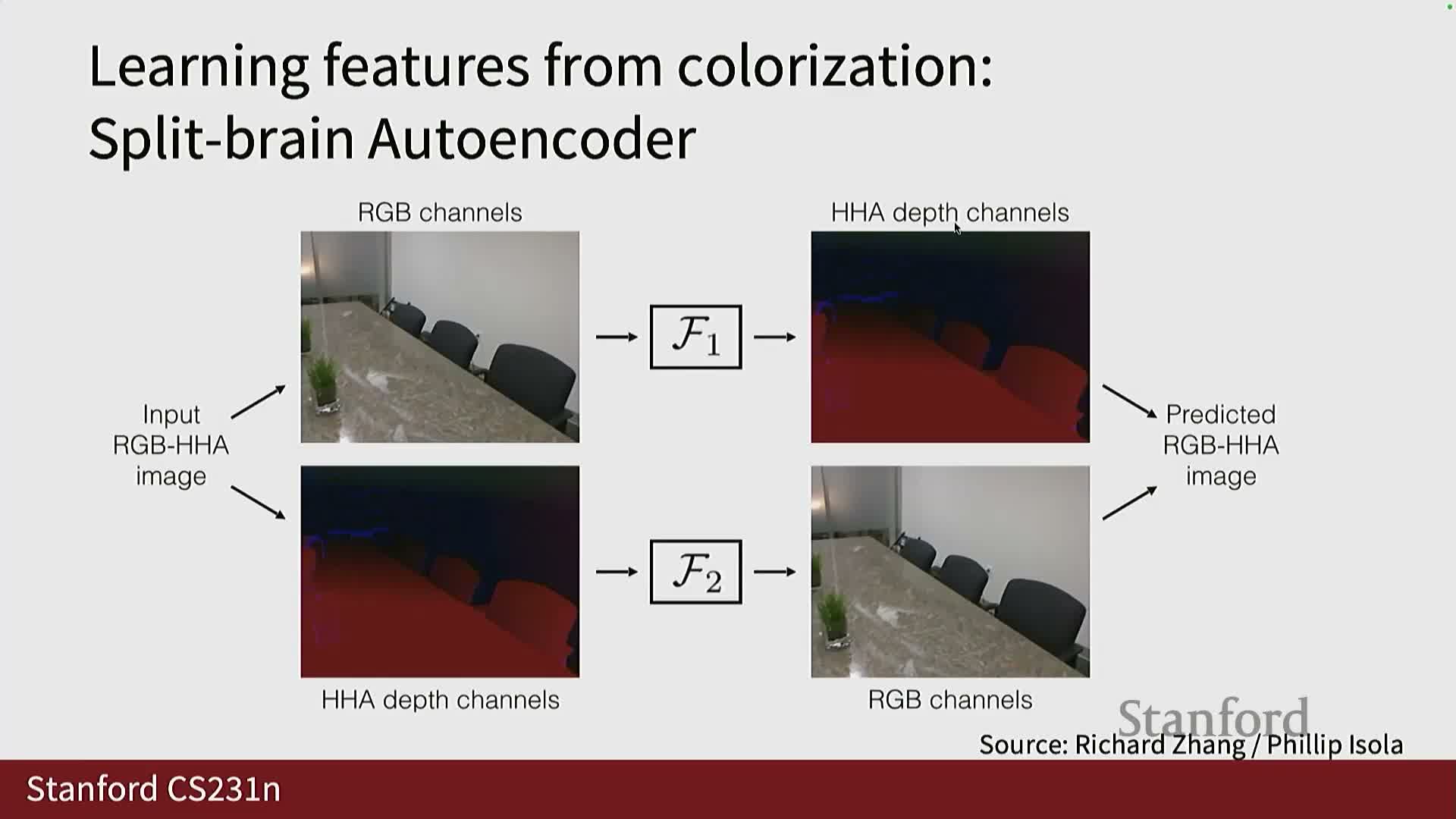

- Colorization and split-brain autoencoders, and extension to video and multimodal prediction

- How encoders learn from pretext labels and architectural choices

- Masked Autoencoders (MAE): ViT-based masking, mask tokens, decoder, and training regimen

- Contrastive representation learning: attract positives, repel negatives and the InfoNCE objective

- SimCLR and the importance of projection heads and batch size in contrastive systems

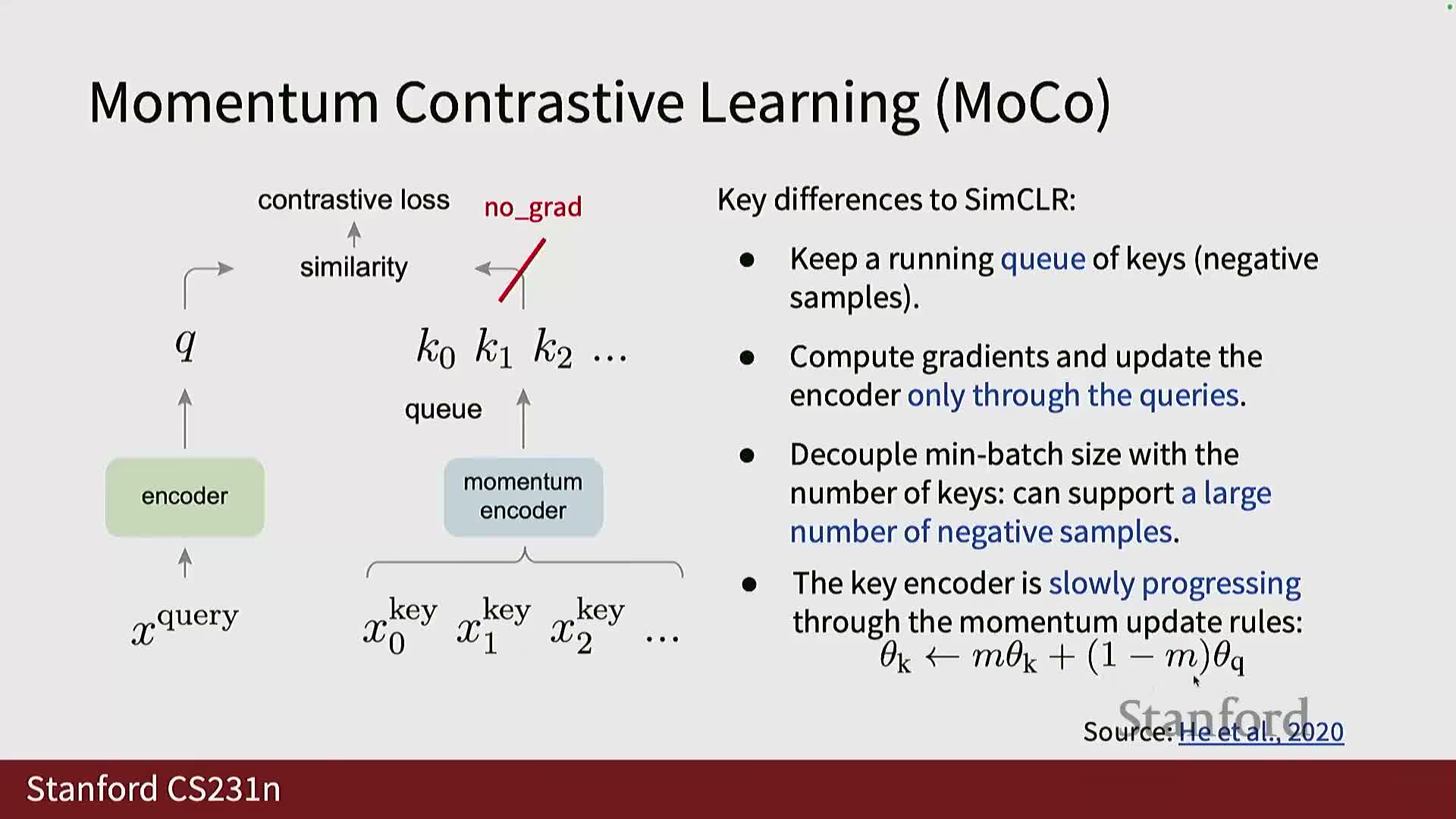

- Momentum Contrast (MoCo), queue-based negatives, and other practical design patterns

- Summary of pretext families and practical guidance for using self-supervised methods

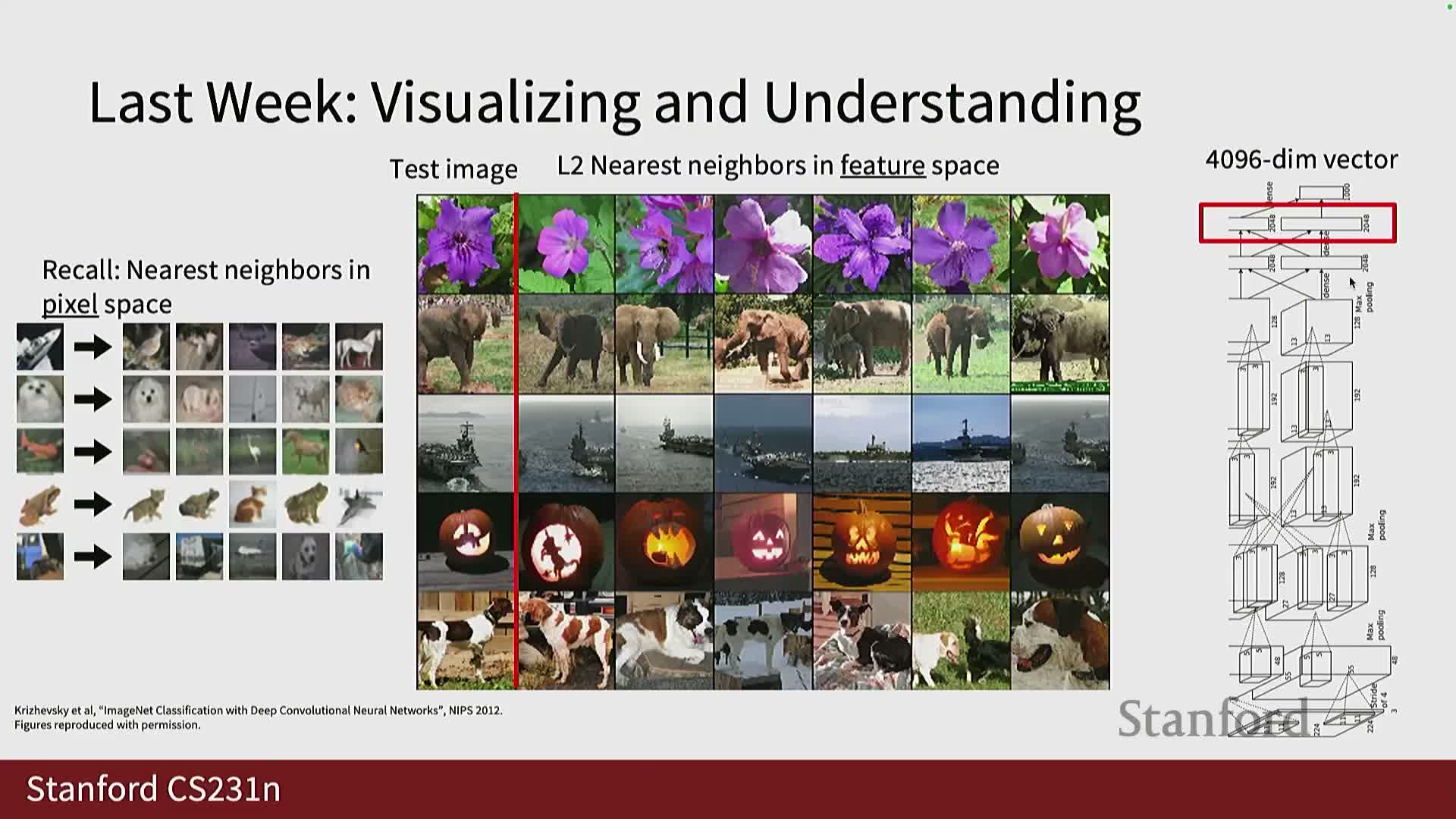

Motivation for self-supervised learning and the role of learned image representations

Learned representations from convolutional or transformer encoders provide compact, semantically meaningful embeddings that enable tasks such as nearest-neighbor classification and downstream linear classifiers.

However, training these encoders at scale with supervised objectives requires large amounts of manual annotation, which is expensive and often infeasible for tasks like segmentation that need per-pixel labels.

Self-supervised learning is motivated by the desire to obtain the same high-quality feature encoders without manual labels by exploiting structure and automatically derivable supervision in raw data.

This segment frames the central engineering trade-off between annotation cost and representation quality, and motivates pretraining on large unlabeled corpora to boost downstream performance.

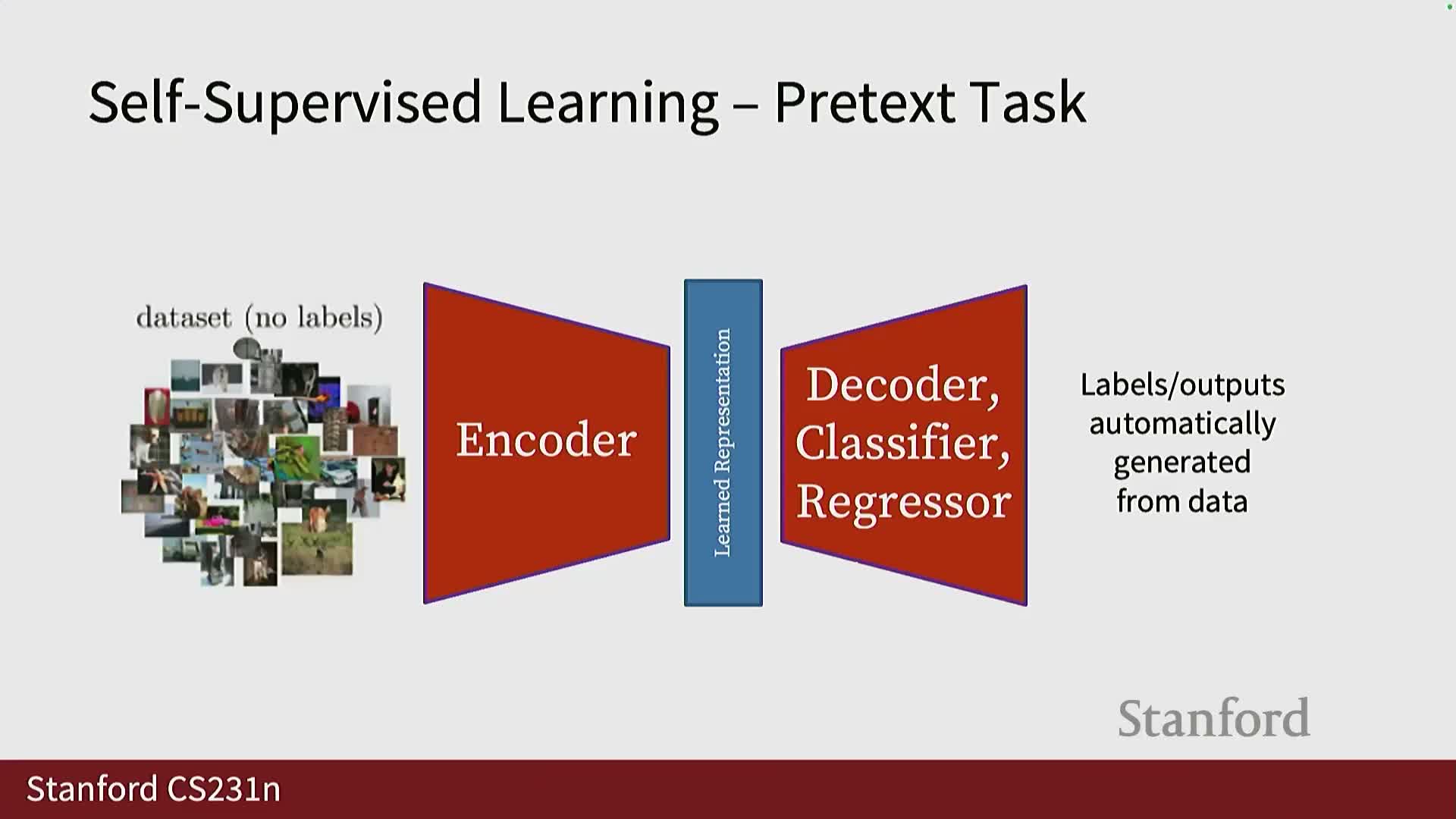

Definition of self-supervised learning: pretext tasks, encoder and decoder, and transfer to downstream tasks

Self-supervised learning (SSL) defines an auxiliary pretext task on unlabeled data that provides pseudo-labels derived from the data itself.

- An encoder network learns representations by optimizing a pretext loss.

- A decoder / classifier / regressor converts those representations to the pretext outputs.

Transfer to downstream tasks proceeds by either freezing or fine-tuning the encoder and attaching a lightweight task-specific head.

- Train encoder + decoder end-to-end on the pretext task with backpropagation.

- Discard or retain the decoder as needed (often a lightweight head is used only during pretraining).

- Transfer the encoder to downstream tasks and either freeze it for linear probing or fine-tune it with a new head.

Architecturally, the decoder can be:

- A small fully connected head for simple pretexts.

- A larger symmetric/asymmetric decoder (autoencoding style) for reconstruction-based tasks.

The goal is that the encoder learns generalizable visual features useful across diverse downstream objectives.

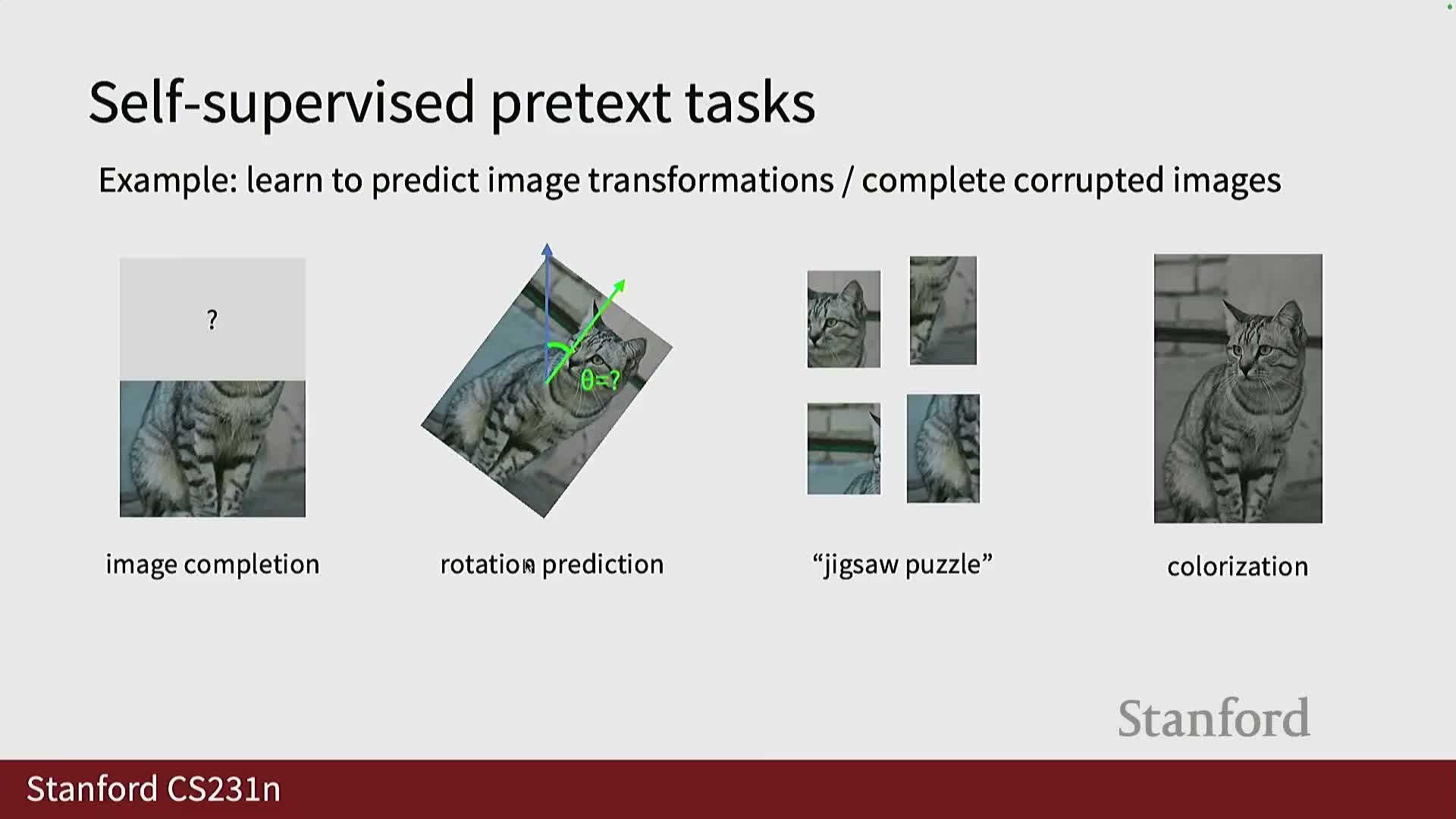

Catalog of common transformation-based pretext tasks

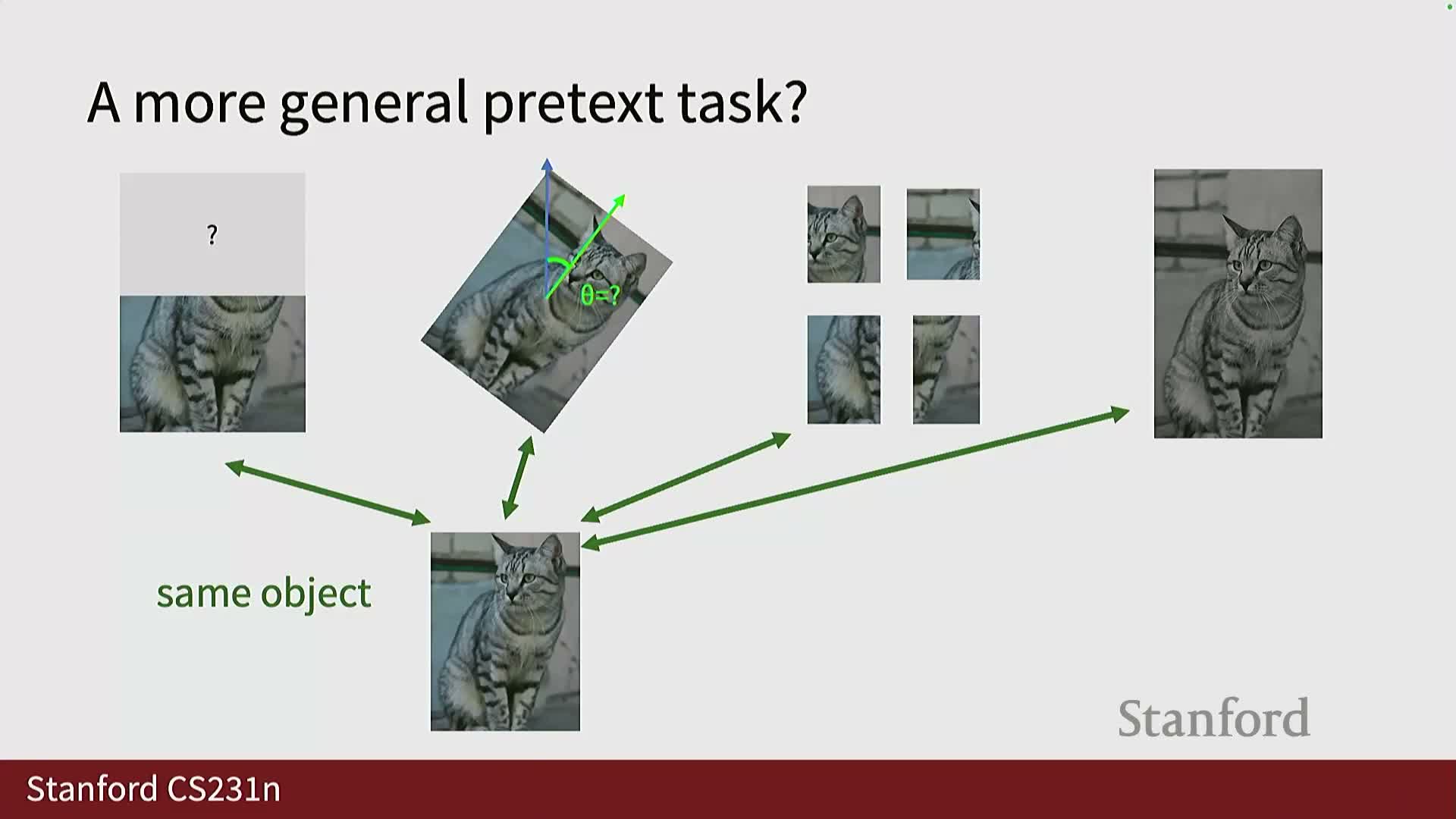

Transformation-based pretext tasks create labels by applying synthetic transformations to inputs and asking the model to predict transformation parameters or to reconstruct the original content.

Canonical examples:

-

Image completion (mask-and-reconstruct) — predict missing pixels or patches.

-

Rotation prediction — classify the applied rotation angle (e.g., 0°, 90°, 180°, 270°).

-

Jigsaw puzzles — predict the correct order or permutation of shuffled patches.

-

Colorization — predict color channels from grayscale input.

These tasks differ in:

-

Output type: classification, regression, or reconstruction.

-

Label generation complexity: how the synthetic labels are produced from the transformation.

-

Induced invariances/equivariances: the kinds of features the task encourages (e.g., spatial layout, color consistency).

Choosing a pretext task requires balancing difficulty and generality:

- The task should be hard enough to force learning rich features.

- It should be generic enough to transfer to many downstream problems.

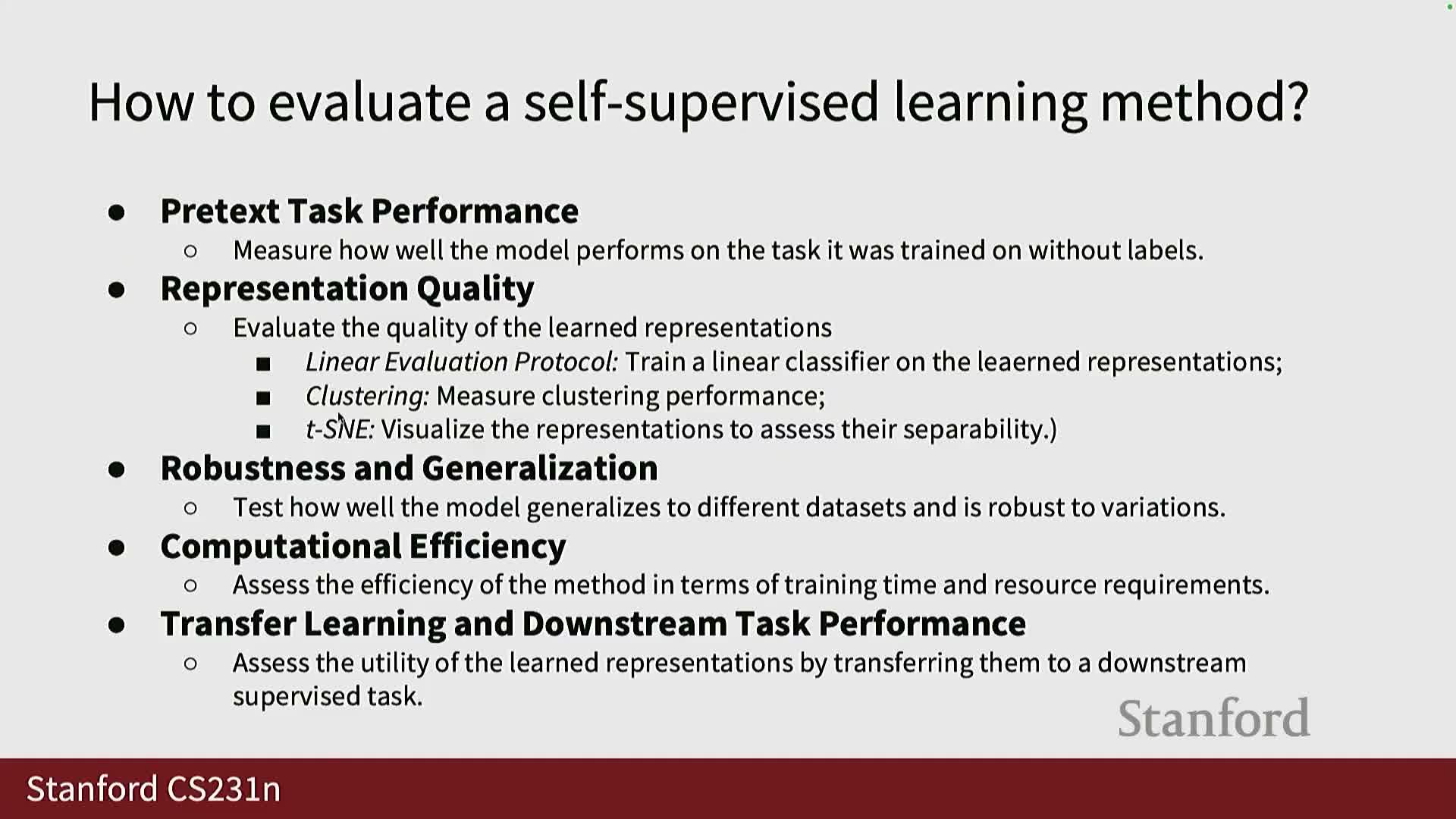

Evaluation dimensions for self-supervised representations

Evaluating self-supervised representation quality requires multiple axes of assessment:

-

Pretext-task accuracy — how well the model solves the pretext objective.

-

Representation utility — linear-probing accuracy when freezing the encoder.

-

Robustness and generalization — performance under perturbations and on out-of-distribution data.

-

Downstream-task performance — final accuracy or sample-efficiency after full fine-tuning (the most decisive metric).

Complementary analysis tools and practical considerations:

-

Visualization (t-SNE, UMAP) and clustering to inspect whether semantic structure is captured.

-

Computational efficiency and robustness to hyperparameters for large-scale pretraining.

Of these, downstream-task performance is primary because SSL’s main goal is to improve accuracy or sample-efficiency on application tasks.

Rotation-prediction as a pretext task and empirical effects

Rotation prediction frames self-supervision as a small multi-class classification problem: randomly rotate an input by one of a small set of angles (e.g., {0°, 90°, 180°, 270°}) and predict which rotation was applied.

- Solving this task forces the encoder to capture global object orientation and coarse shape cues—visual “common sense.”

- Empirically, rotation pretraining accelerates convergence and improves downstream accuracy relative to random initialization.

- When combined with partial fine-tuning (e.g., freezing early layers, fine-tuning later layers), it yields strong performance on classification, detection, and segmentation benchmarks.

On some datasets, rotation-pretrained encoders can approach the utility of ImageNet-supervised pretraining, though supervised pretraining can still outperform self-supervised methods on very hard tasks or when labels are plentiful.

Patch-based pretext tasks: relative patch location and jigsaw permutation

Patch-based tasks decompose an image into a grid (e.g., 3×3) and ask the model to predict spatial relationships or the global permutation of shuffled patches.

-

Relative-location formulation: an eight-way classification predicting a patch’s offset relative to a center patch.

-

Jigsaw formulation: predict the permutation index of a shuffled patch set (global ordering).

Because the full permutation space (9!) is enormous, practical implementations:

- Restrict candidate permutations (e.g., a lookup table of 64 well-separated permutations) to create a tractable multi-class classification task.

Learning these tasks encourages the encoder to reason about spatial layout, parts, and coarse semantics useful for downstream tasks.

Inpainting (masking) pretext tasks and reconstruction loss design

Inpainting pretext tasks mask parts of an image and train an encoder–decoder to reconstruct the missing pixels, creating targets from uncorrupted images so no manual labels are needed.

- Training typically uses a reconstruction loss (commonly L2 / mean-squared error) computed only over masked regions; implemented via element-wise multiplication with a binary mask to ignore unmasked pixels.

- Pure pixelwise losses tend to produce blurry outputs, so many systems augment the reconstruction objective with adversarial or perceptual losses to encourage realistic, high-frequency detail.

- Architecturally this is an asymmetric autoencoder: the encoder processes visible regions and a decoder synthesizes full patches.

The reconstruction objective yields usable decoders and produces encoders that capture contextual and semantic information necessary to predict missing content.

Colorization and split-brain autoencoders, and extension to video and multimodal prediction

Colorization uses a color space that separates luminance from chrominance (e.g., Lab) and formulates self-supervision as predicting color channels (A,B) from the lightness channel (L).

- This forces the encoder to infer object identity and material from grayscale cues.

- The split‑brain autoencoder extends this by training two subnetworks to predict complementary channel sets from each other (e.g., one predicts color from luminance, the other predicts luminance from color) and concatenating learned features.

- The cross-modal prediction idea generalizes to RGB‑D (predict depth from RGB) and to video colorization, where a reference colored frame provides targets for subsequent frames and an attention-based copying mechanism transfers color information.

Colorization-based pretexts serve both practical applications (colorizing images/video) and representation learning by exploiting natural cross‑channel or cross‑frame consistency.

How encoders learn from pretext labels and architectural choices

Pretext labels are derived from the data transformation applied to each sample, and the encoder learns relevant features because the training loop backpropagates the discrepancy between decoder outputs and those automatically generated targets.

- The encoder is thus optimized to extract features predictive of the pretext labels, analogous to supervised training on class labels.

- Architectures may be symmetric (classic autoencoder) or asymmetric, and encoder/decoder weights need not be shared.

- Often the decoder is a lightweight head used only during pretraining while the encoder (ResNet, ViT, etc.) is retained for downstream tasks.

Design choices that affect transferability:

- Whether to use separate networks, tied weights, or different capacities for encoder and decoder.

- The pretext task formulation and decoder complexity, which influence what the encoder learns and how well it transfers.

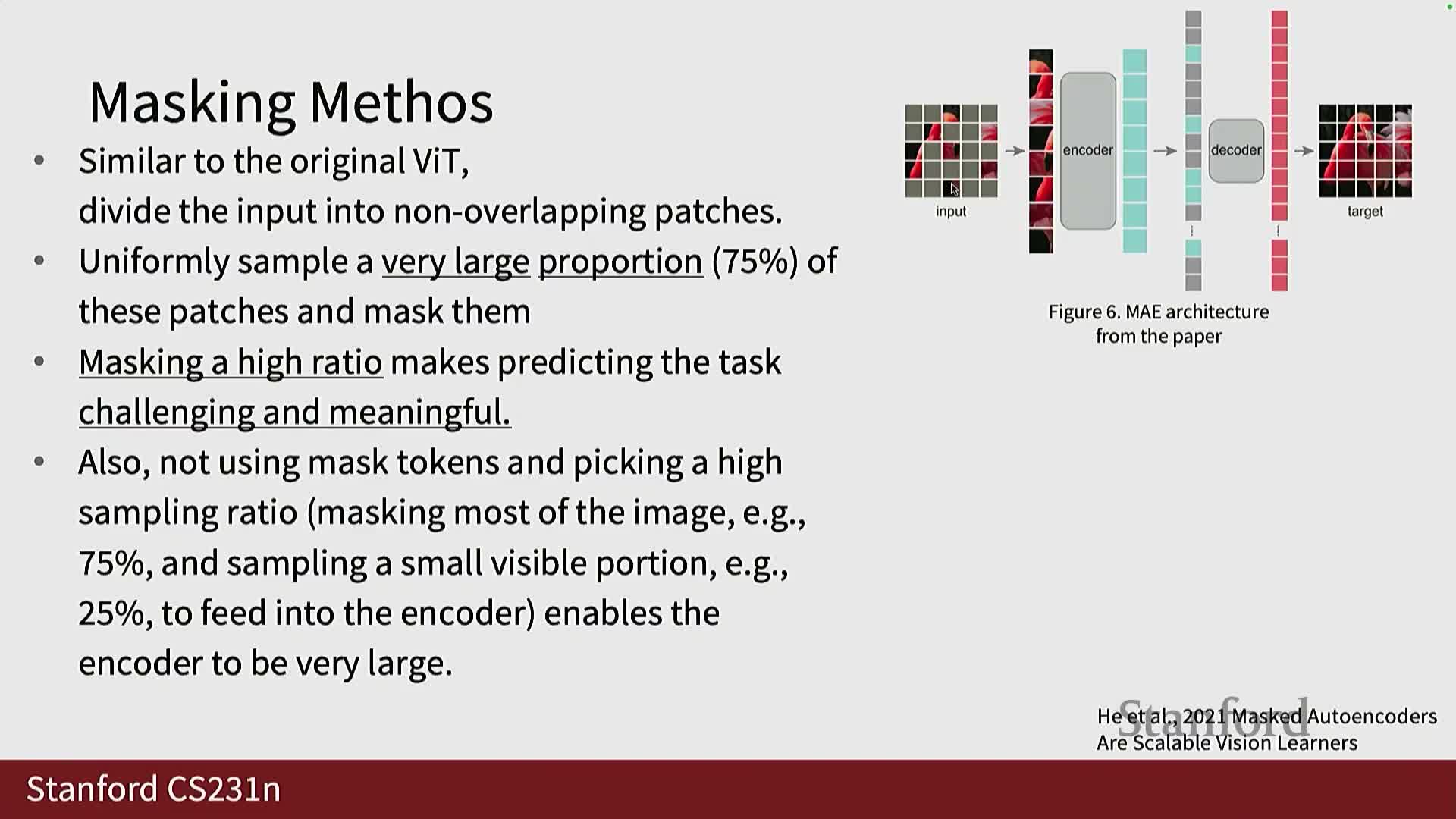

Masked Autoencoders (MAE): ViT-based masking, mask tokens, decoder, and training regimen

Masked Autoencoders (MAE) apply high-ratio random masking (e.g., 75% of image patches) and use a Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder that ingests only the unmasked patches.

- Each masked position is represented by a learnable mask token so that the full sequence (encoded visible patch tokens + mask tokens) can be processed by a lightweight decoder to reconstruct pixel values or patch embeddings.

- The encoder uses patch embeddings with positional encodings (as in ViT); the decoder operates on the full-length token sequence and outputs reconstructed patch predictions.

- Training typically minimizes an L2 reconstruction loss computed only on masked patches.

Benefits and important hyperparameters:

-

Aggressive masking increases task difficulty and training efficiency (many different mask realizations per image).

- Key hyperparameters: masking ratio, decoder depth/width, mask token design, reconstruction target, and mask sampling strategy (random vs block-based).

Trained encoders are evaluated via linear probing or full fine-tuning to measure representation quality.

Contrastive representation learning: attract positives, repel negatives and the InfoNCE objective

Contrastive learning frames representation learning as maximizing agreement between views of the same image (positives) while minimizing similarity to other images (negatives).

- A scoring function s(·,·) measures similarity in embedding space.

- The loss converts scores to probabilities (via softmax) so that the positive pair receives high probability while negatives occupy the denominator.

The canonical objective is InfoNCE:

- For a query x the loss is -log[ exp(s(x, x+) / τ) / Σ_i exp(s(x, x_i) / τ ) ] where x+ is a positive, x_i are negatives, and τ is a temperature.

- InfoNCE lower-bounds mutual information between positive pairs; larger numbers of negatives tighten this bound and empirically improve performance, motivating large minibatches or mechanisms to reuse historical negatives.

SimCLR and the importance of projection heads and batch size in contrastive systems

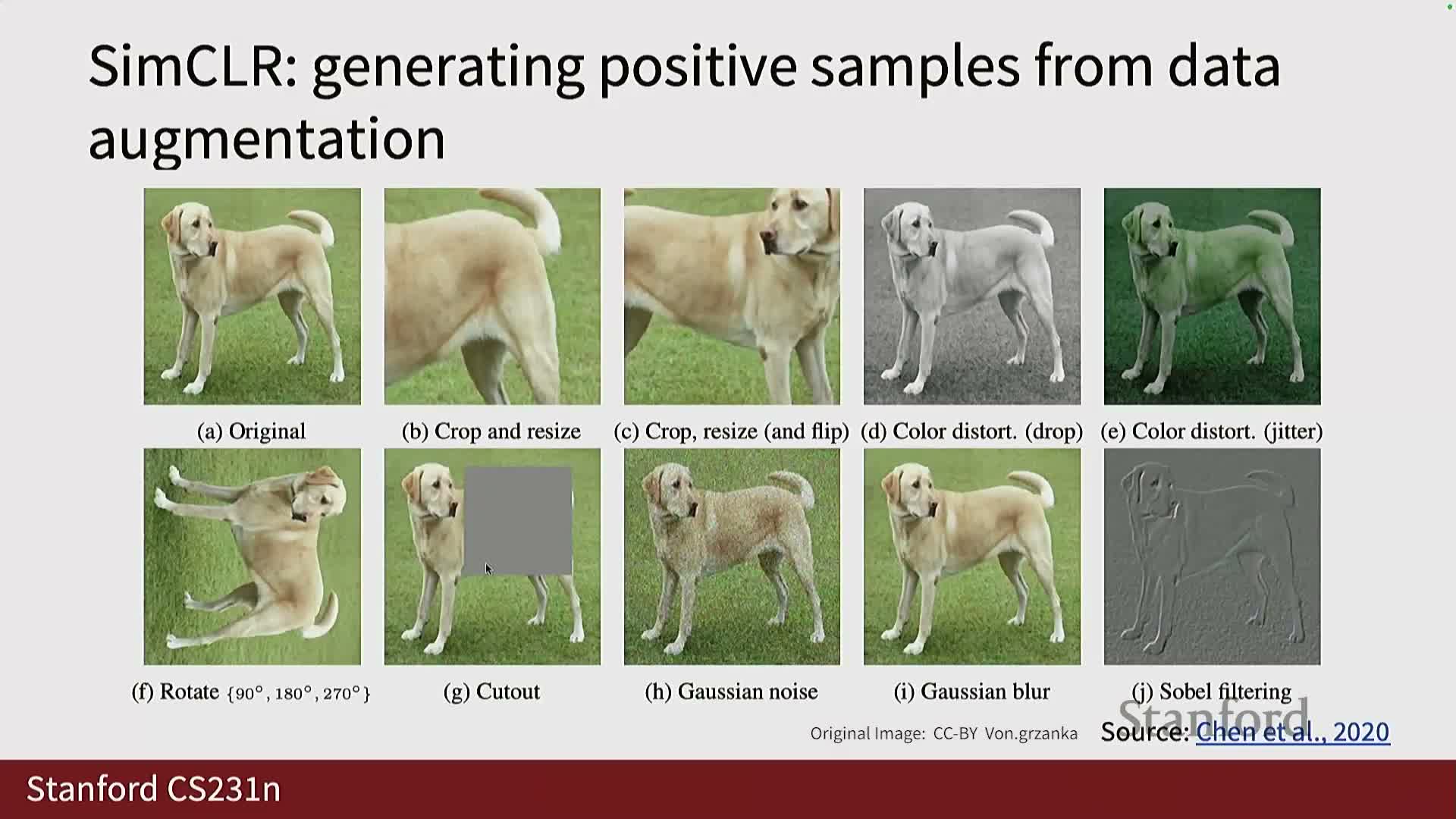

SimCLR generates two augmented views of each image, encodes them with a shared encoder, and computes contrastive loss on projected representations z obtained via a small MLP projection head.

- The projection head isolates the contrastive objective to a subspace so the pre-projection representation preserves information not needed for contrastive discrimination, improving downstream transfer.

- SimCLR shows that heavy data augmentation, a nonlinear projection head, and very large batch sizes (to provide many negatives in-batch) are critical for high accuracy.

- The large-batch requirement motivated follow-ups that replace in-batch negatives with external memory or momentum queues to reduce per-step memory pressure.

Momentum Contrast (MoCo), queue-based negatives, and other practical design patterns

MoCo addresses the large-batch negative-sample problem by maintaining a dynamic queue of encoded keys (negatives) and a separate momentum-updated encoder for those keys.

- The query encoder is trained by contrasting with many queued negatives while the key encoder is updated as an exponential moving average of the query encoder to provide consistent representations.

- Historical negatives are stored outside the current computational graph, preventing backpropagation through them and enabling large effective negative sets without huge minibatches.

- This architecture requires careful momentum and queue-size tuning.

Empirical follow-ups (MoCo v2/v3) show that combining projection heads, stronger augmentations, and momentum mechanisms yields state-of-the-art representations.

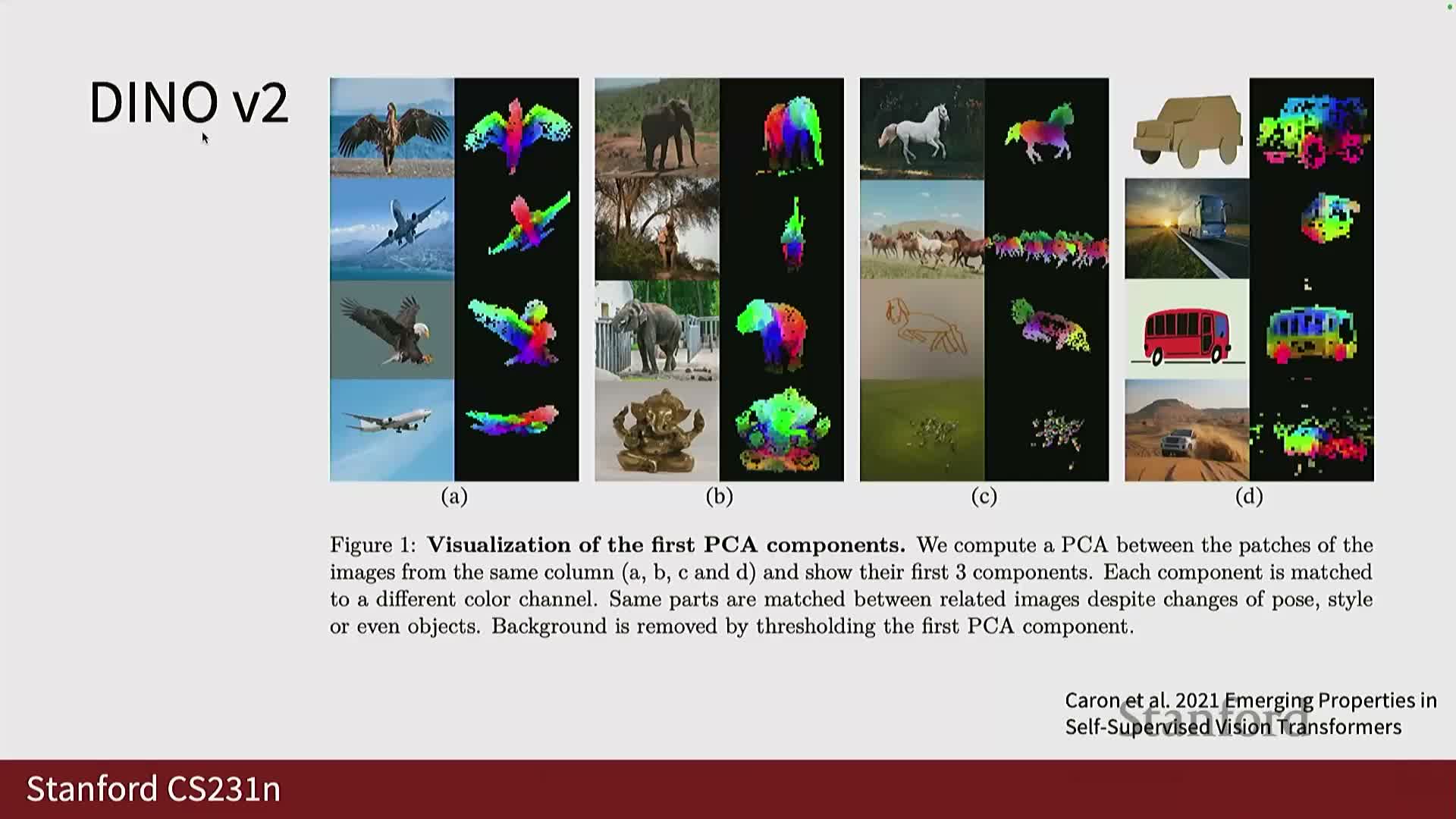

Alternative paradigms include predictive coding (CPC) and student–teacher schemes like DINO that remove or reinterpret negative sampling.

Summary of pretext families and practical guidance for using self-supervised methods

Transformation-based pretext tasks (rotation, jigsaw, colorization, inpainting), masked reconstruction (MAE), and contrastive/object-centered methods (SimCLR, MoCo, CPC, DINO) constitute the main families of self-supervised approaches for images and video.

- Each family exposes complementary inductive biases: spatial layout, cross-channel consistency, context reconstruction, instance discrimination.

- Practical adoption requires choosing a pretext that matches available data and compute budget (e.g., MAE scales well with ViT and aggressive masking; contrastive methods require many negatives or queues).

- Validate representations with linear probing and downstream fine-tuning, and tune hyperparameters such as masking ratio, projection head depth, temperature, batch size, or queue length to optimize transfer performance.

These frameworks generalize beyond vision to language, speech, and robotics because they exploit abundant raw data and automatically derived supervision to learn transferable encoders.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: