Stanford CS231N Deep Learning for Computer Vision | Spring 2025 | Lecture 15- 3D Vision

- Lecture scope and overview of 3D vision topics

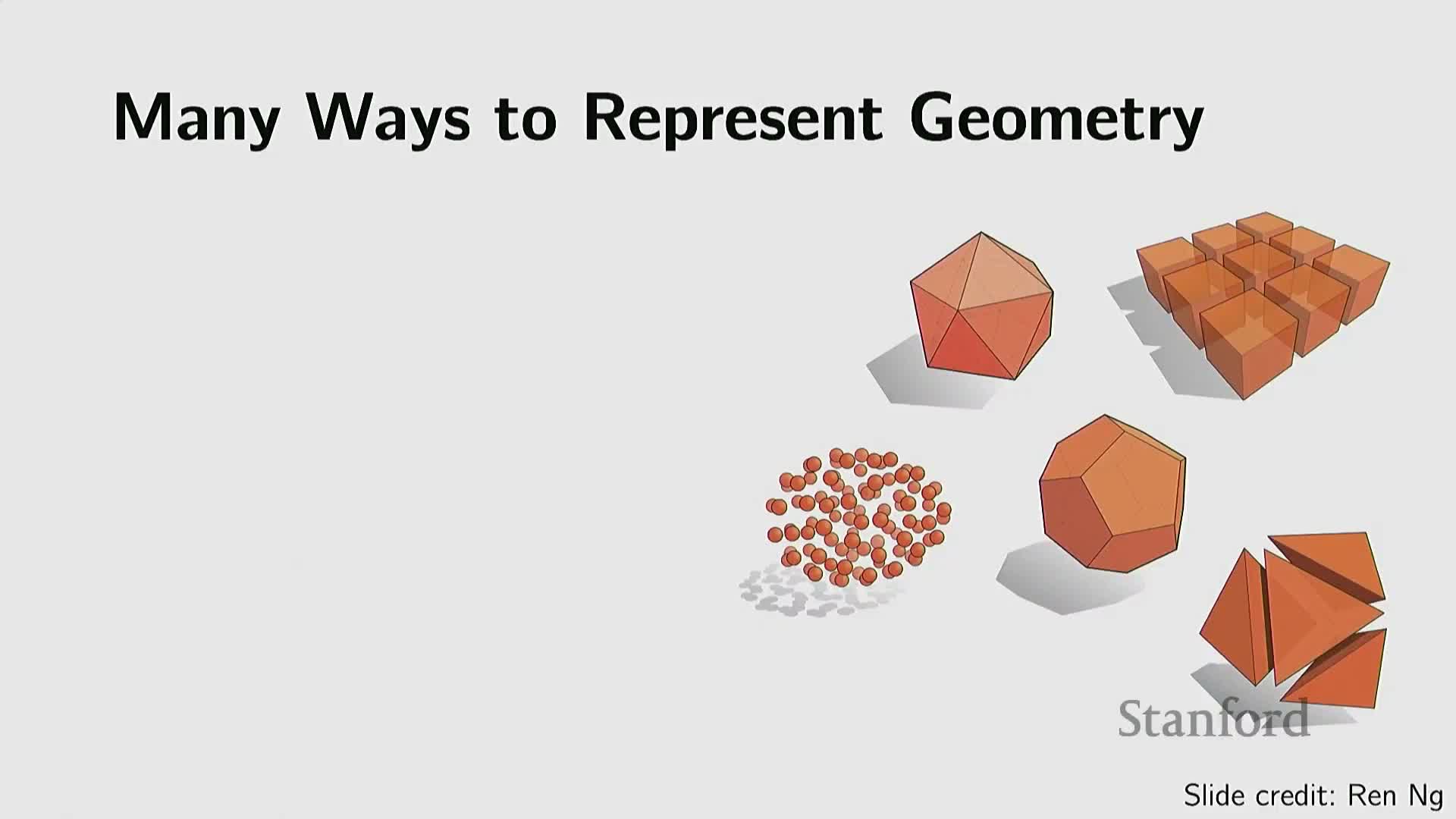

- 3D representations bifurcate into explicit and implicit categories

- Representation selection depends on storage, editing, rendering and downstream integration

- Point clouds provide a simple, sensor-native explicit geometry format but lack connectivity

- Polygonal meshes capture connectivity and support graphics operations such as subdivision and simplification

- Parametric representations express surfaces via low‑dimensional control functions and enable smooth, compact models

- Explicit representations simplify sampling but complicate inside/outside queries, motivating implicit alternatives

- Precomputing implicit fields on regular grids produces level sets and voxels that enable uniform indexing

- Voxels enabled early volumetric deep learning via straightforward 3D convolution analogs

- 3D dataset scale and diversity evolved from small benchmarks to millions of synthetic and scanned models

- Core 3D vision tasks include generation, reconstruction, discriminative recognition and joint 2D–3D modeling

- Rendering 3D models to multiple 2D views enables reuse of mature 2D image networks

- Volumetric generative models and hierarchical grids (octrees) scale 3D convolutional approaches

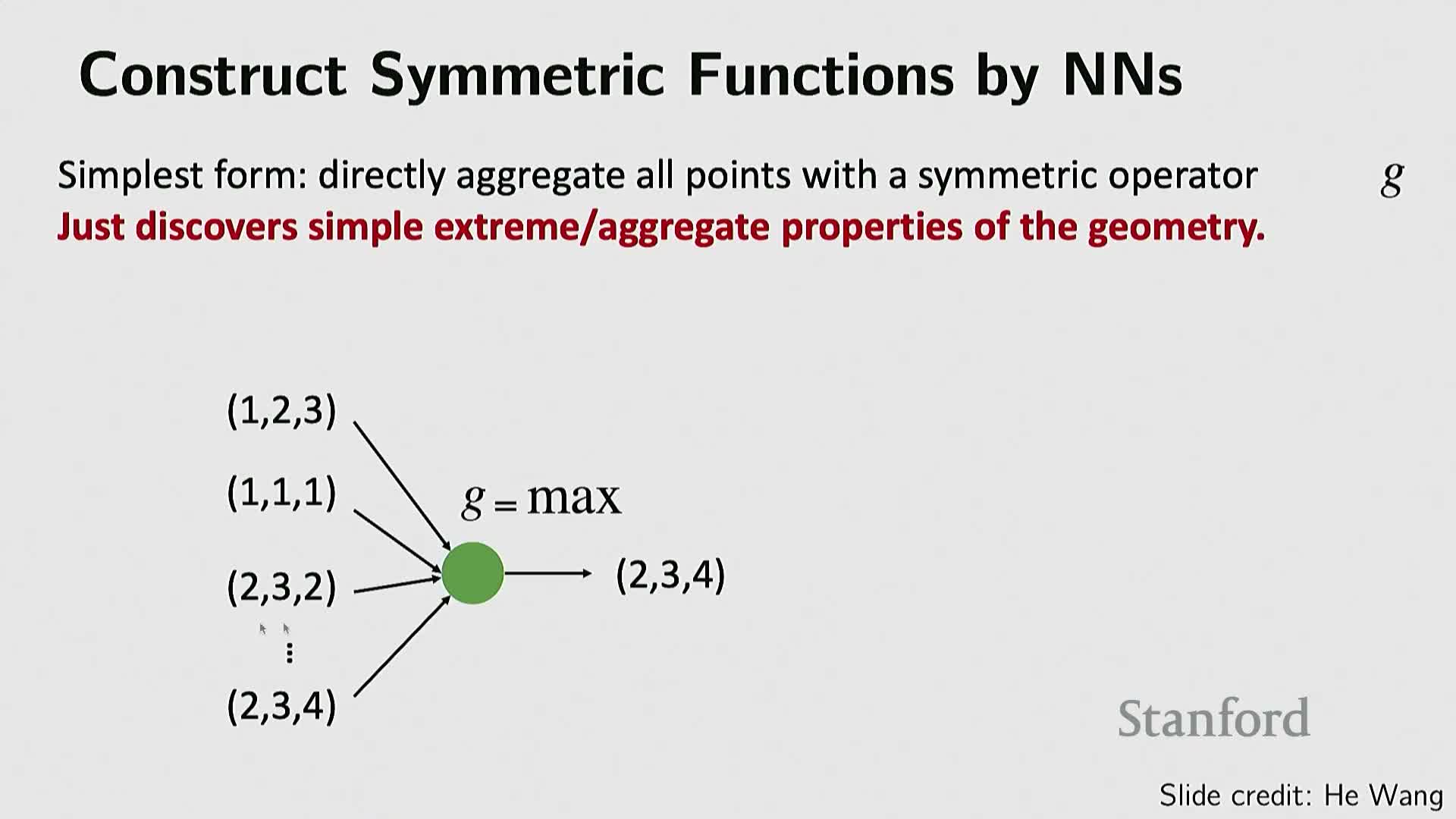

- PointNet family adapts neural architectures to unordered, sampled point clouds via symmetric aggregation

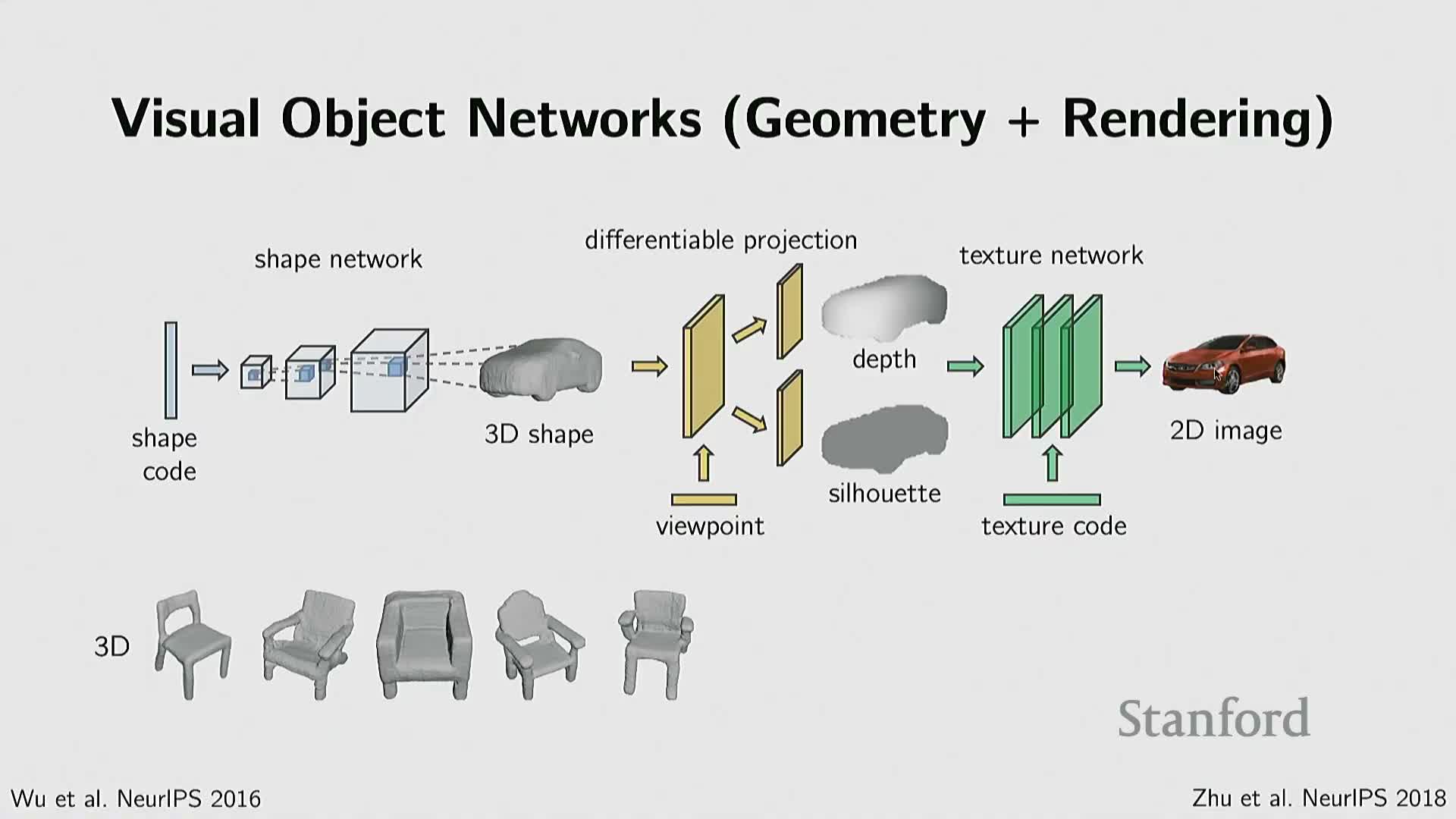

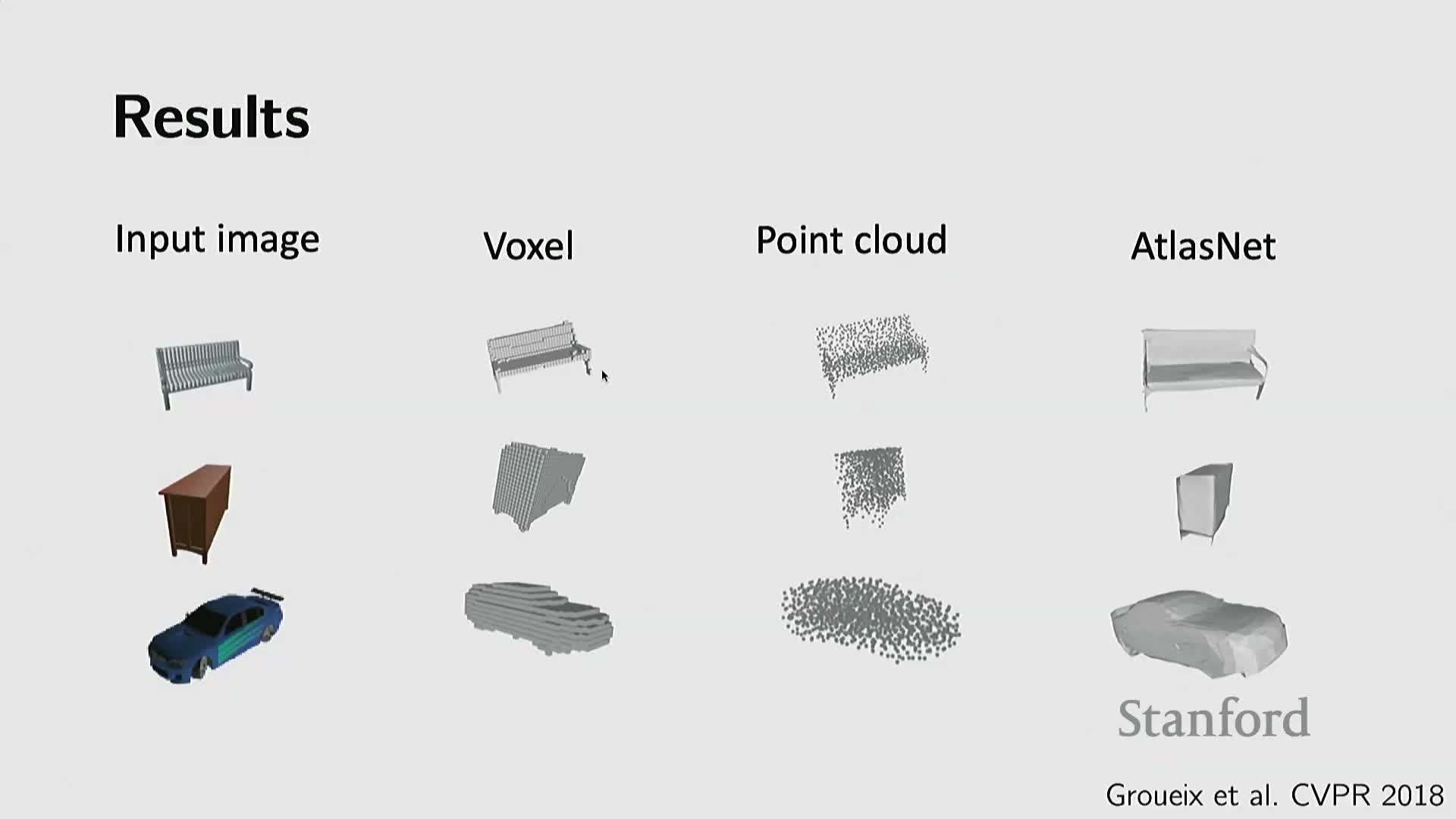

- Atlas-style networks learn parametric mappings from low-dimensional parameter domains to 3D surfaces

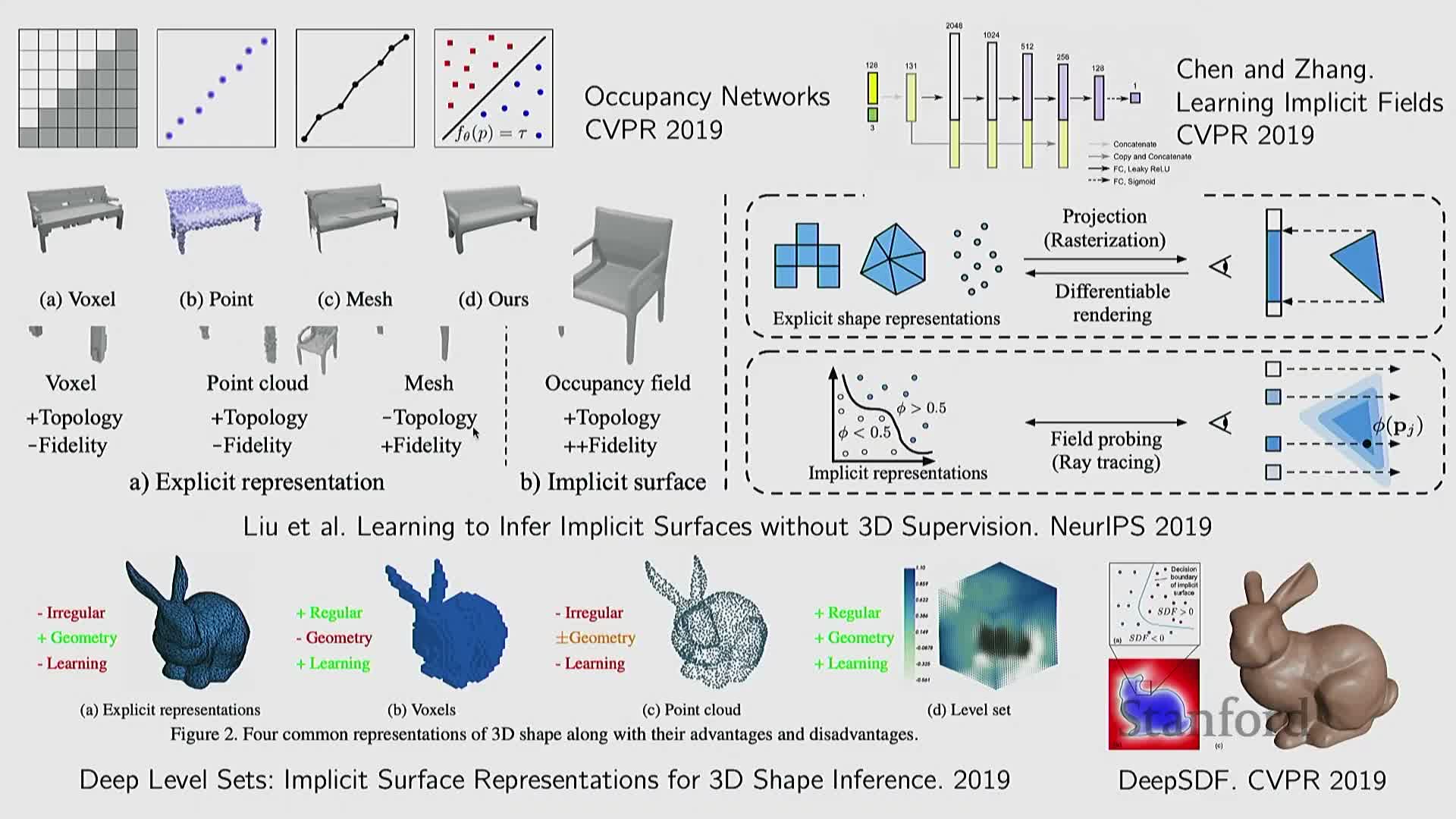

- Deep implicit functions and occupancy/SDF networks treat neural networks as continuous geometry queries

- NeRF introduces neural radiance fields and differentiable volumetric rendering to learn appearance and geometry from images

- Generative radiance fields and hybrid 3D+2D adversarial training produce controllable, realistic 3D object models

- NeRF efficiency limitations motivated sparse, point-based rendering such as Gaussian splatting

- Modeling structural regularities, hierarchies and programmatic generation captures object semantics beyond local geometry

Lecture scope and overview of 3D vision topics

This segment defines the scope of 3D vision covered in the talk and frames the lecture objectives: to survey 3D geometry representations, contrast explicit and implicit approaches, and explain how modern deep learning integrates with these representations for generation, reconstruction, rendering, and animation.

The segment positions 3D vision relative to recent 2D advances—convolutional networks, transformers, and generative image models—and highlights multimodal perception, robotics, and embodied AI as major application drivers.

It also outlines the lecture roadmap:

- Representation taxonomy (what formats exist and why),

- Representation-specific algorithms and trade-offs, and

-

Representative deep learning methods and datasets.

The intent is to provide both conceptual foundations and concrete pointers to deep-learning architectures and use cases for common 3D tasks.

3D representations bifurcate into explicit and implicit categories

3D object geometry falls into two broad categories: explicit and implicit representations.

- Explicit representations directly list geometric primitives such as point clouds, polygonal meshes, and subdivision surfaces. They provide direct geometric interpretation and are widely supported by graphics operations.

-

Implicit representations encode geometry as a function or constraint—for example level sets, algebraic surfaces, or distance functions—where the surface is a zero-level set or sign/density field over space and naturally supports classification-type queries about points.

Each category has distinct strengths and weaknesses across:

- storage and sampling,

- topology handling, and

-

integration with downstream algorithms and neural networks.

Understanding this taxonomy is foundational for choosing data structures and neural architectures for 3D vision tasks.

Representation selection depends on storage, editing, rendering and downstream integration

Choosing a 3D representation depends on the application and several practical criteria:

- Compact storage versus fidelity.

- Numerical regularity and conditioning for optimization.

- Support for editing operations (e.g., smoothing, subdivision, simplification).

- Fusion of multi-sensor scans (registration and merging).

- Rendering to 2D pixels and compatibility with differentiable rendering.

-

Integration with neural methods for generation or inverse problems.

Different pipelines prioritize different properties:

- Sensor-native point clouds minimize acquisition processing.

- Meshes and parametric surfaces facilitate smooth rendering and topology-aware editing.

-

Implicit functions simplify point-in-volume queries and functional composition.

The chosen representation also constrains how to condition on inputs (images, language) and impacts computational costs for operations like registration, animation, or differentiable rendering. These practical criteria guide the explicit vs implicit trade-offs in real systems.

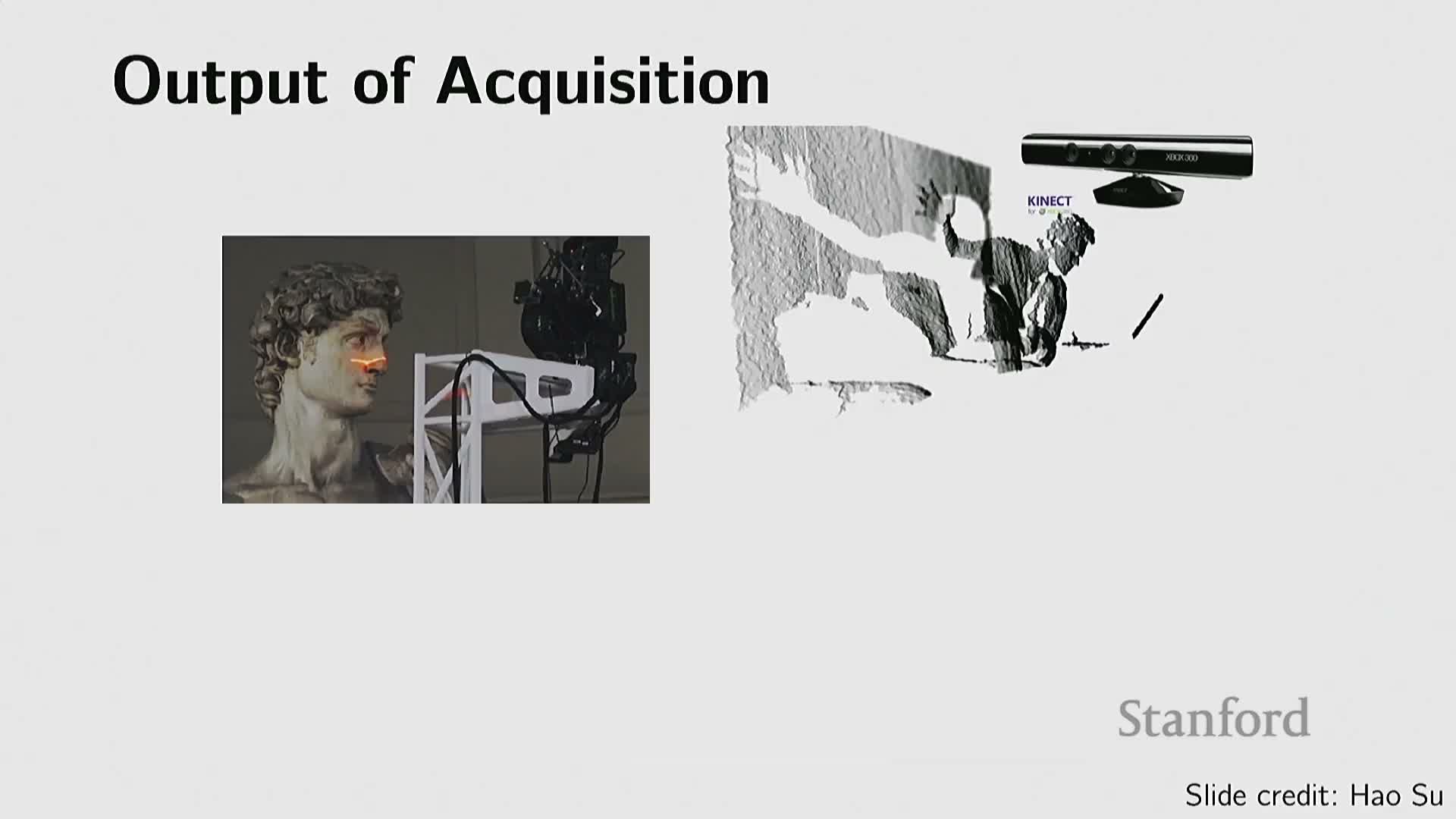

Point clouds provide a simple, sensor-native explicit geometry format but lack connectivity

Point clouds represent geometry as an unordered set of 3D sample points (commonly a 3×N coordinate array), optionally with normals or other attributes to support shading and rendering.

- They are directly produced by many depth sensors and scanners and can represent arbitrary topology.

- They lack explicit connectivity and topology information, which complicates surface-continuity tasks, smooth rendering, and topological reasoning.

- Point clouds are often noisy and unevenly sampled, requiring registration, denoising, and resampling. Algorithms typically enforce or encourage uniform sampling and estimate per-point normals to improve rendering or reconstruction.

Because of their simplicity and sensor alignment, point clouds remain a foundational explicit representation but frequently require conversion or augmentation for many graphics and learning tasks.

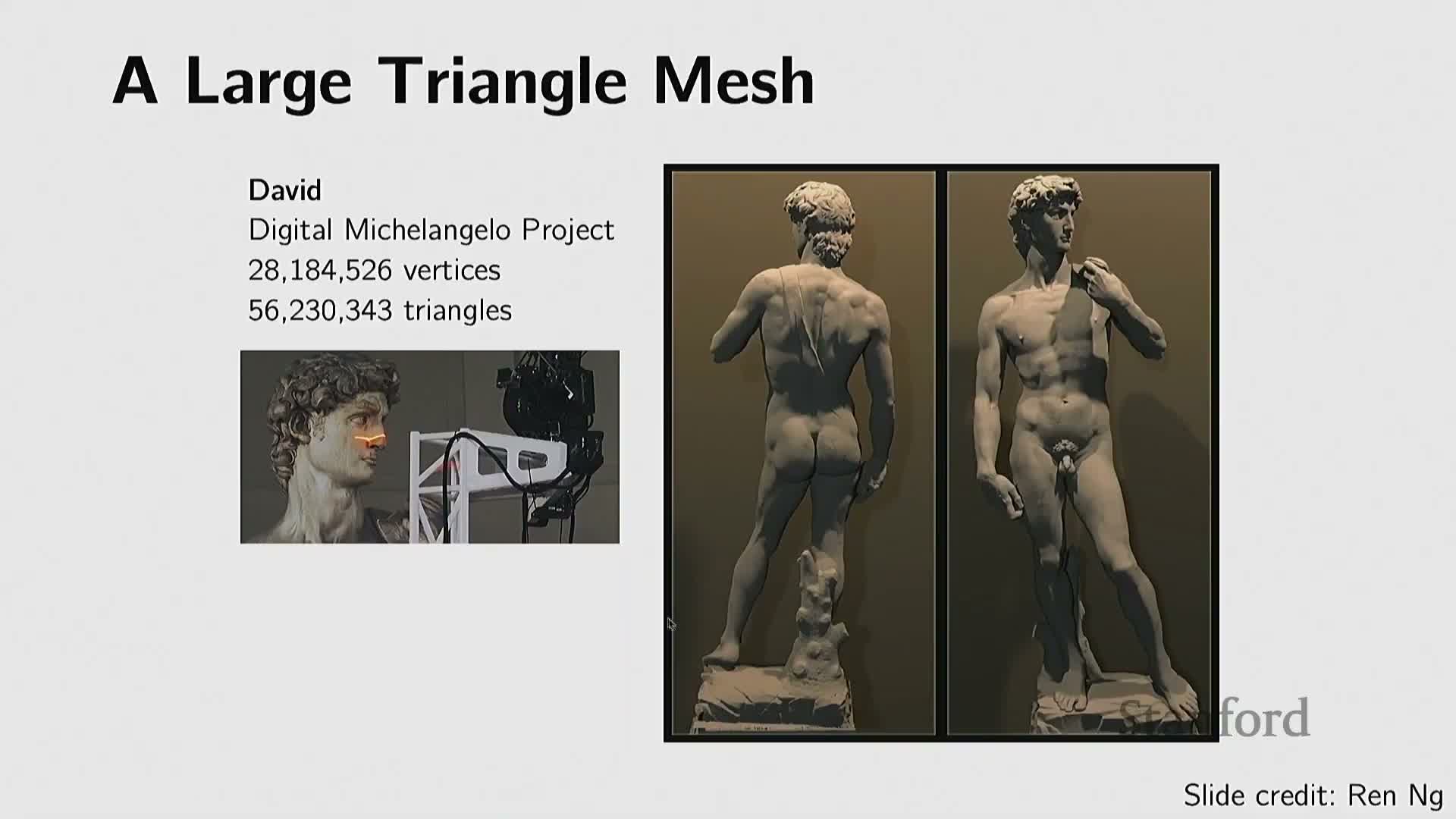

Polygonal meshes capture connectivity and support graphics operations such as subdivision and simplification

Polygonal meshes augment point sets with explicit faces and connectivity (most commonly triangles), providing surface topology and enabling high-quality rendering in graphics engines and games.

- Meshes support a rich set of geometric processing operations: normal computation, subdivision (increase detail), simplification (reduce complexity), remeshing (regularize element sizes), and topology-aware repairs.

- This capability makes meshes the de facto format for high-fidelity geometry in many pipelines.

Challenges:

- Meshes are irregular data structures (variable face valence and resolution), which complicates direct integration with classical neural networks expecting fixed-grid inputs.

- This irregularity motivated specialized network architectures and preprocessing strategies.

Large scanned models and urban datasets show meshes’ ability to represent detailed surfaces but also highlight the memory and processing demands of dense triangular meshes.

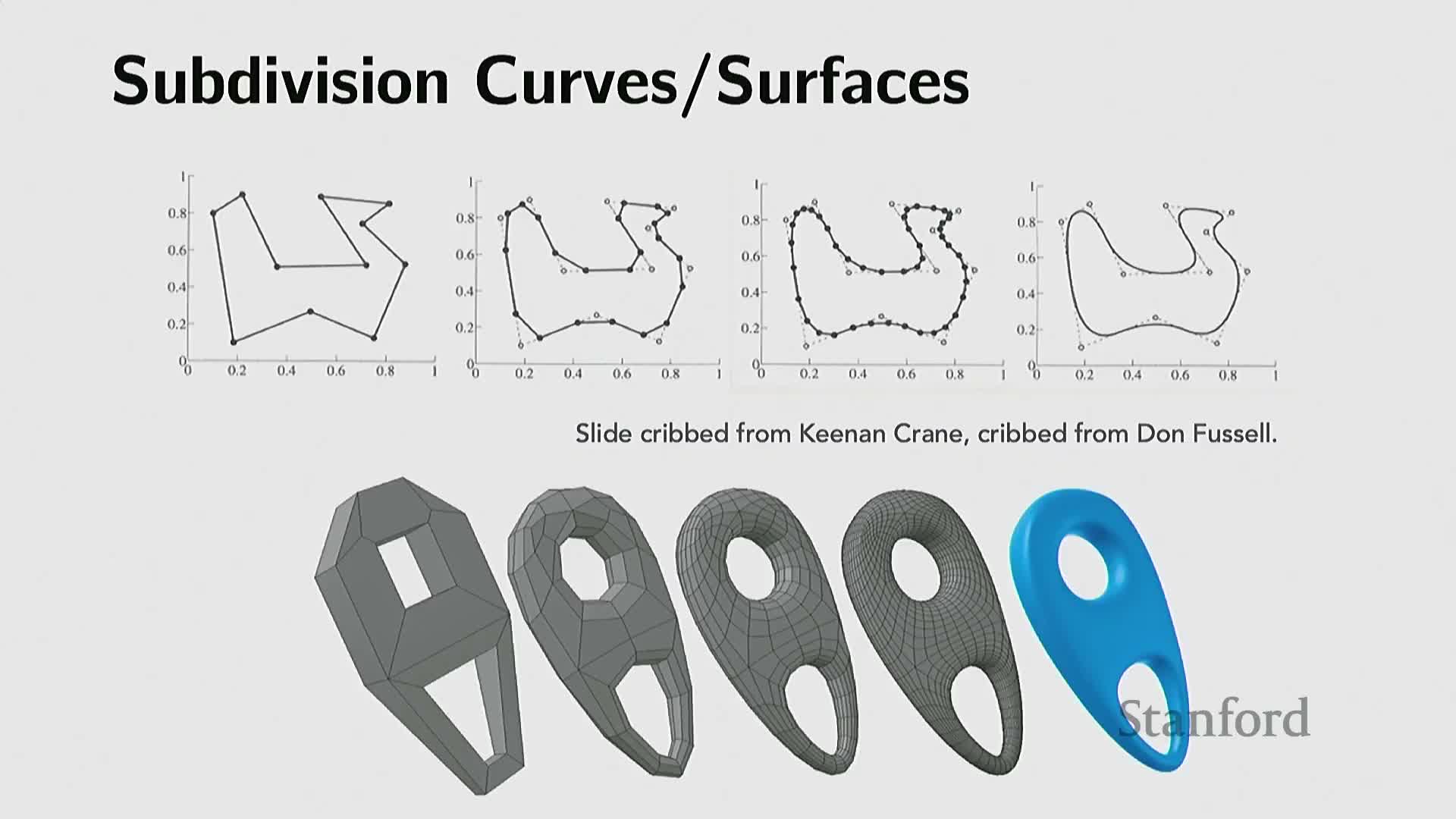

Parametric representations express surfaces via low‑dimensional control functions and enable smooth, compact models

Parametric representations use analytic or basis-function mappings from a low-dimensional parameter domain (for example u,v on a 2D patch or t on a curve) into 3D space—examples include splines, Bézier patches, and NURBS.

- They exploit low intrinsic dimensionality: a small set of control points or basis parameters can express large, smooth geometry regions.

- Support operations like exact evaluation, refinement, and hierarchical subdivision.

- Especially effective for engineered shapes with regular structure (straight edges, circular arcs) and are widely used in CAD and industrial design where exactness and constructive composition matter.

Parametric forms make sampling straightforward (sample parameter coordinates and evaluate). Limitations: they can struggle to express very complex or highly irregular organic geometry without many patches and careful parameterization.

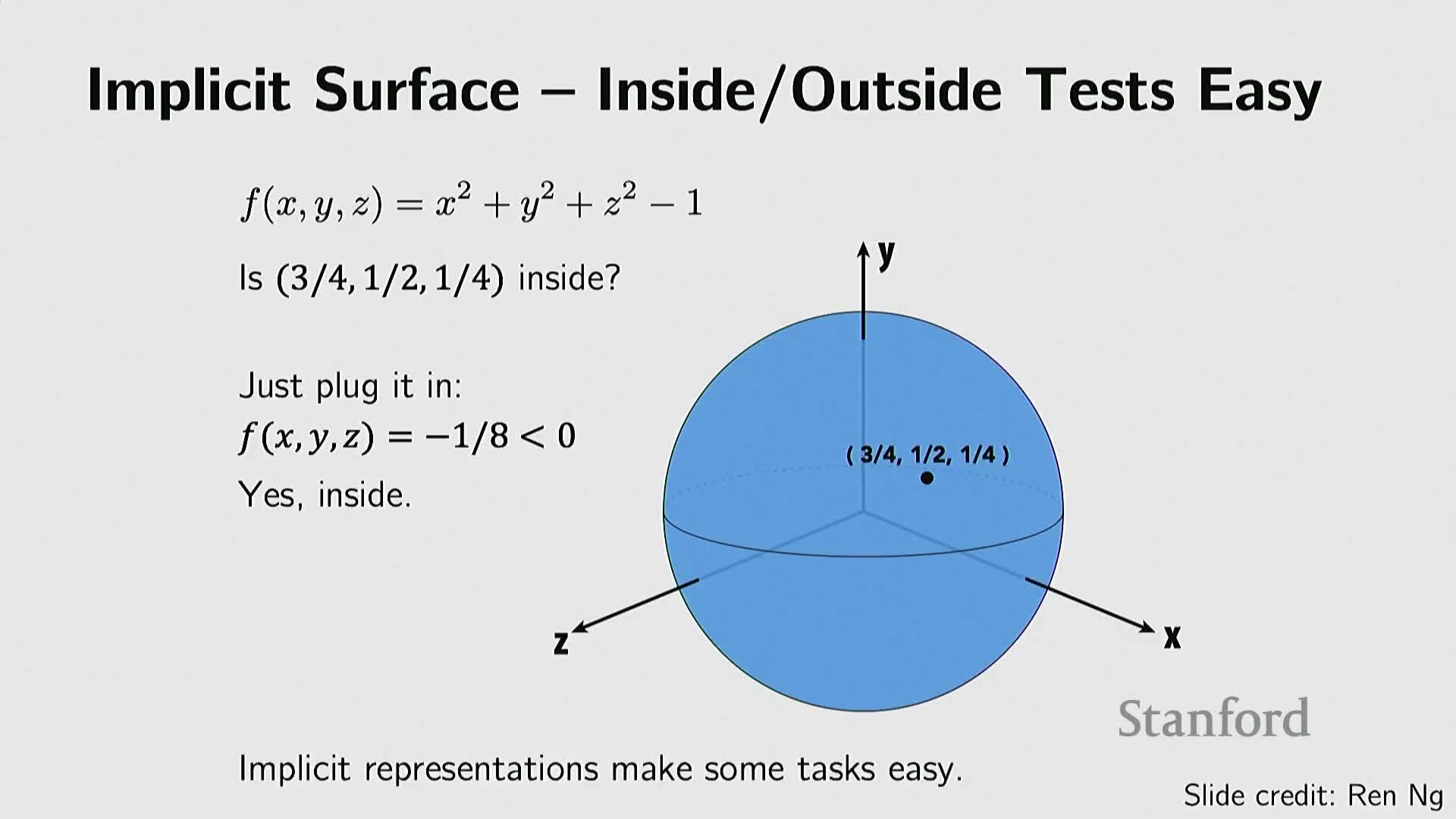

Explicit representations simplify sampling but complicate inside/outside queries, motivating implicit alternatives

Explicit formats (point clouds, meshes, parametric patches) provide direct access to surface samples and make geometric sampling and surface extraction straightforward.

In contrast, implicit representations encode geometry as a function f(x) whose sign, zero level set, or density value determines inside/outside classification, distance-to-surface, or volumetric occupancy. This makes tasks like ray queries and differentiable rendering simpler.

Trade-offs:

- Explicit formats: easy sampling on the surface, direct element access, but poor at answering arbitrary point-in-volume queries.

- Implicit formats: easy evaluation (point classification, boolean ops, blending), but harder to sample uniformly on the surface and may lack closed-form surface parametrizations for complex shapes.

This core trade-off—easy sampling versus easy evaluation—guides representation choice depending on whether the application prioritizes surface sampling, collision queries, or differentiable rendering.

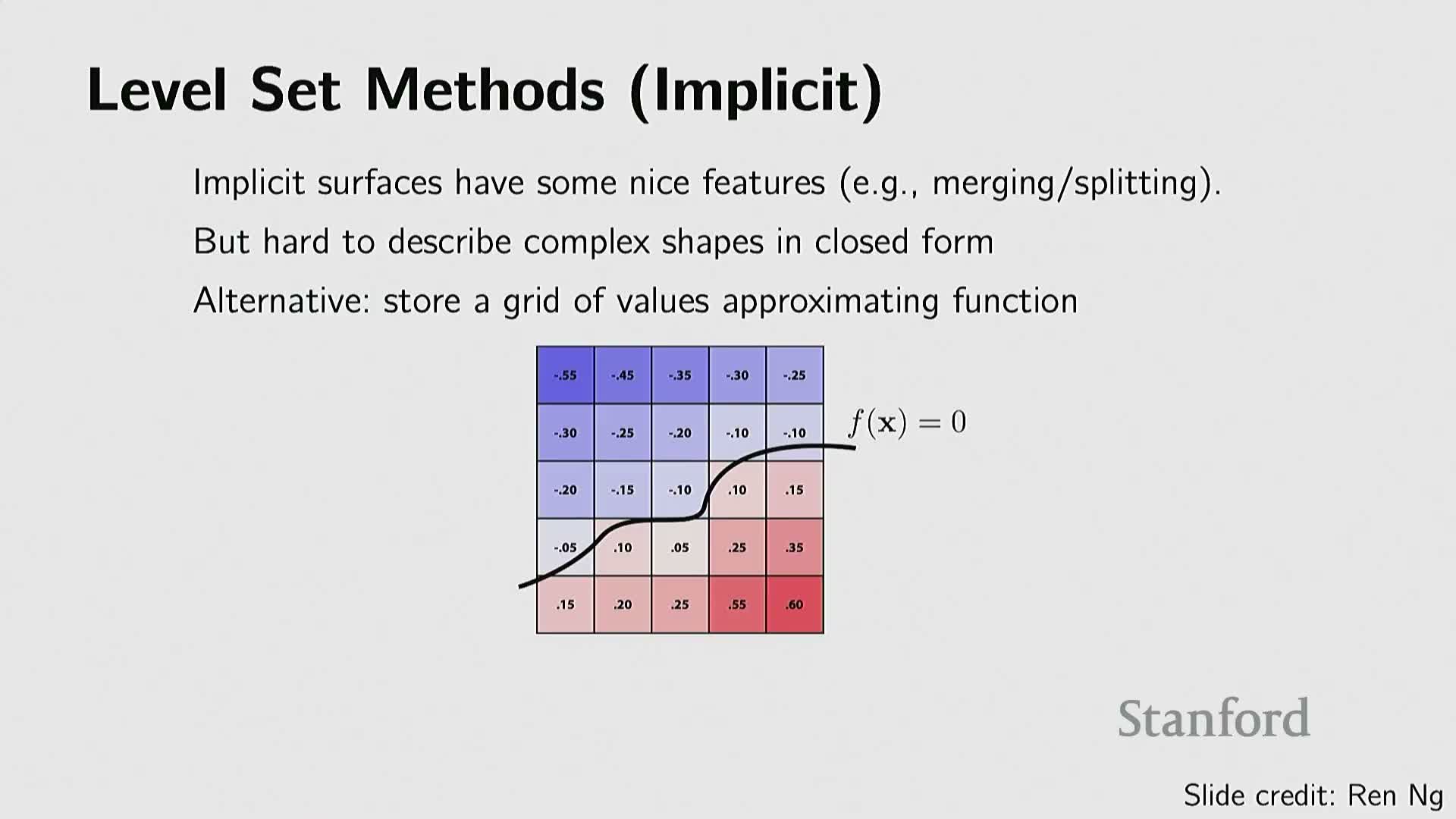

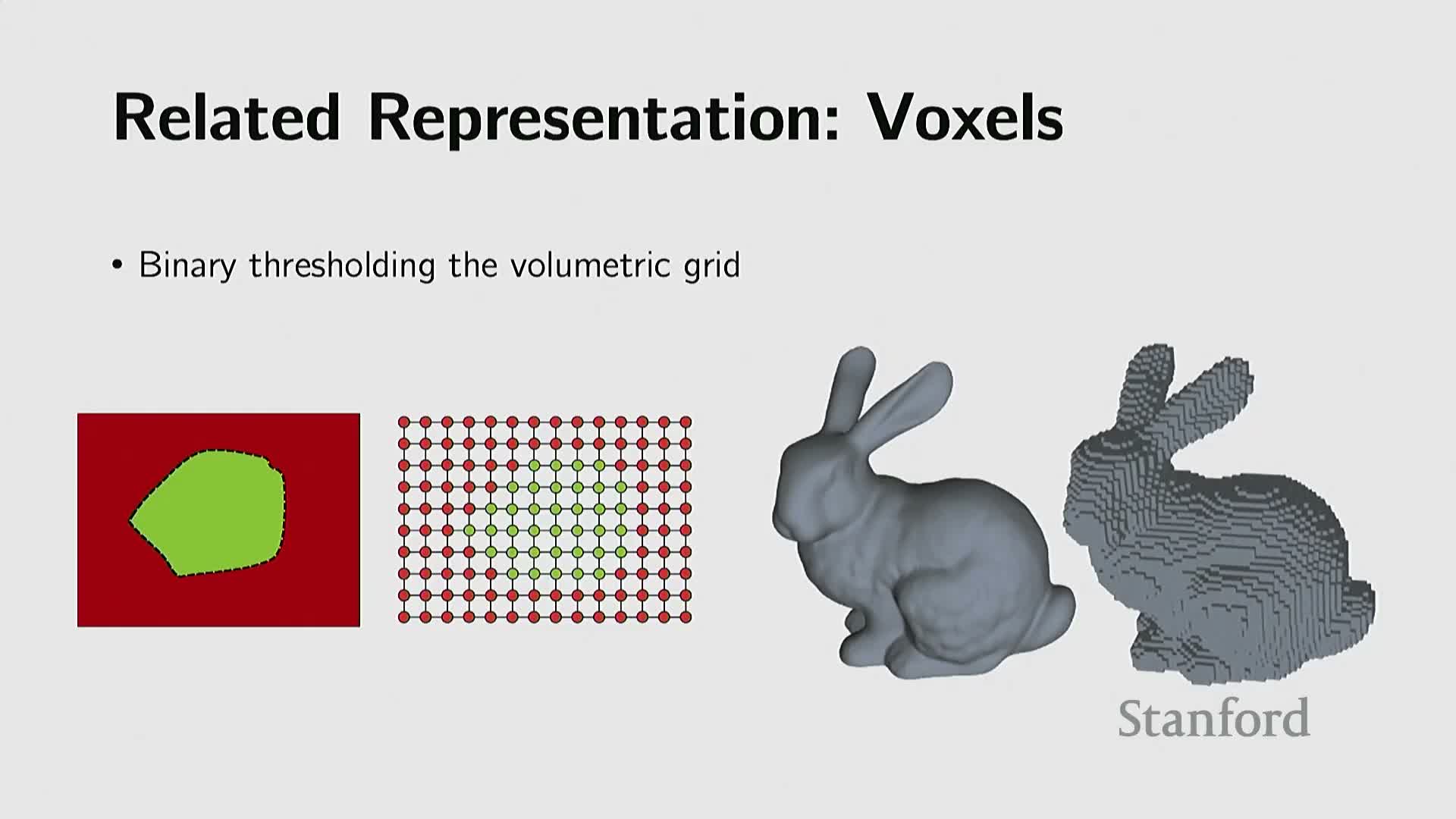

Precomputing implicit fields on regular grids produces level sets and voxels that enable uniform indexing

A common engineering approach is to discretize an implicit field by evaluating the implicit function or distance field on a uniform 3D grid, producing a dense volumetric array of signed distances or occupancy values.

- This yields level-set representations and, after binarization, voxel occupancy grids.

- Precomputation turns functional implicit representations into explicit array data structures that support simple indexing and visualization.

- Surface extraction is possible via contouring algorithms (e.g., marching cubes) from sign changes between adjacent voxels.

Pros and cons:

- The grid analogy to 2D pixels allows direct application of 3D convolutions and differentiable volumetric algorithms.

- Uniform grids waste memory and compute in empty space and have limited resolution for a fixed memory budget.

Voxels therefore form a practical bridge between implicit theory and neural architectures at the cost of sampling inefficiency and limited fidelity.

Voxels enabled early volumetric deep learning via straightforward 3D convolution analogs

Early deep-learning work in 3D favored voxels because they generalize 2D pixel grids to 3D arrays, enabling straightforward extension of 2D convolutional and generative architectures to volumetric convolutions and deconvolutions.

- This made it easy for computer-vision researchers to reuse existing CNN tooling and pretraining methods, facilitating the first 3D generative models and classifiers trained on voxelized datasets.

- Graphics researchers criticized voxels for inefficiency and low fidelity at a given memory budget, spurring work on sparse or hierarchical voxel structures (e.g., octrees) and alternative native 3D representations.

Despite limitations, voxels played a pivotal role in bootstrapping volume-based neural methods: a practical engineering trade-off that prioritized rapid porting of mature 2D techniques over computational efficiency.

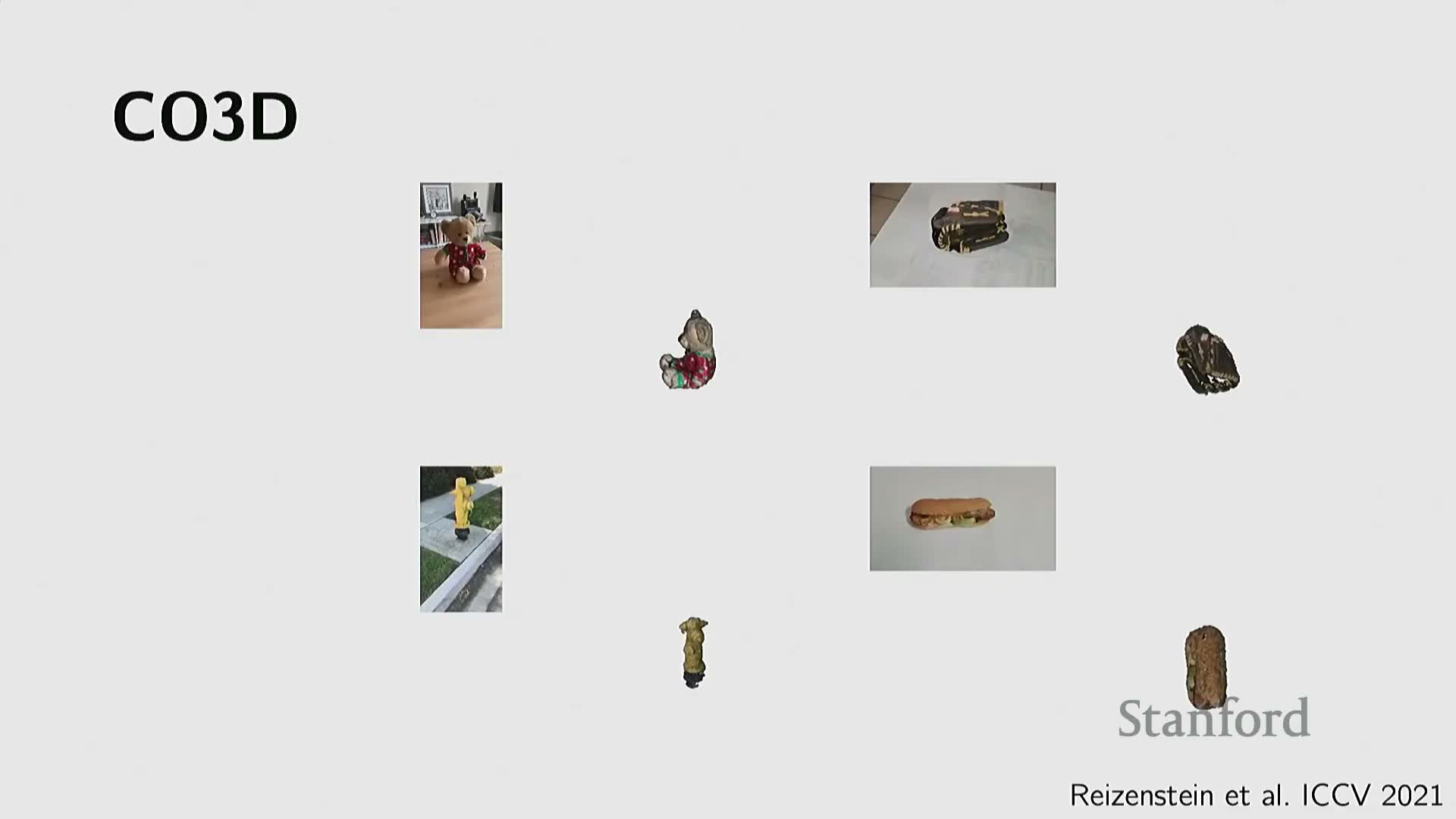

3D dataset scale and diversity evolved from small benchmarks to millions of synthetic and scanned models

3D dataset availability progressed through several stages:

- Compact academic collections (e.g., Princeton Shape Benchmark, ~1,800 models).

- Large synthetic repositories (e.g., ShapeNet, millions of CAD models with a curated 50k core).

- Massive asset libraries (e.g., Objaverse, Objaverse-XL) containing millions of textured models.

In parallel, scanned datasets capture real-world instances (e.g., Redwood, curated iPhone-scanned object sets) and scene-centric scans (indoor room scans) that provide spatial context, part labels, and mobility attributes.

Key limitations and consequences:

- 3D training datasets remain orders of magnitude smaller and more costly to acquire than large 2D image corpora.

- This constraint influences supervised learning and motivates methods that leverage 2D priors, multi-view supervision, or self-supervision.

- Dataset scale and annotation type strongly shape which learning paradigms—synthetic generation, image-based reconstruction, or part-based modeling—are viable.

Core 3D vision tasks include generation, reconstruction, discriminative recognition and joint 2D–3D modeling

Key tasks in 3D vision include:

- Generative modeling (unconditional or conditional shape and scene synthesis).

- Reconstruction from images (single- or multi-view inverse rendering).

- Geometry processing (completion, simplification, repair).

-

Discriminative tasks (classification, segmentation) tailored to 3D inputs.

Many systems model 2D and 3D jointly because large-scale 2D datasets and pretrained 2D foundation models provide valuable appearance and photographic priors that improve 3D reconstruction and rendering fidelity.

Multimodal fusion extends beyond vision—examples include robotics with tactile sensing, LiDAR for autonomous driving, and textual conditioning for generative tasks—requiring architectures that combine diverse inputs and constraints.

Task selection heavily influences representation and architecture choices:

- Generation and high-quality rendering often favor implicit radiance fields or parametric surfaces.

-

Classification and segmentation may exploit multi-view projections or point-cloud networks.

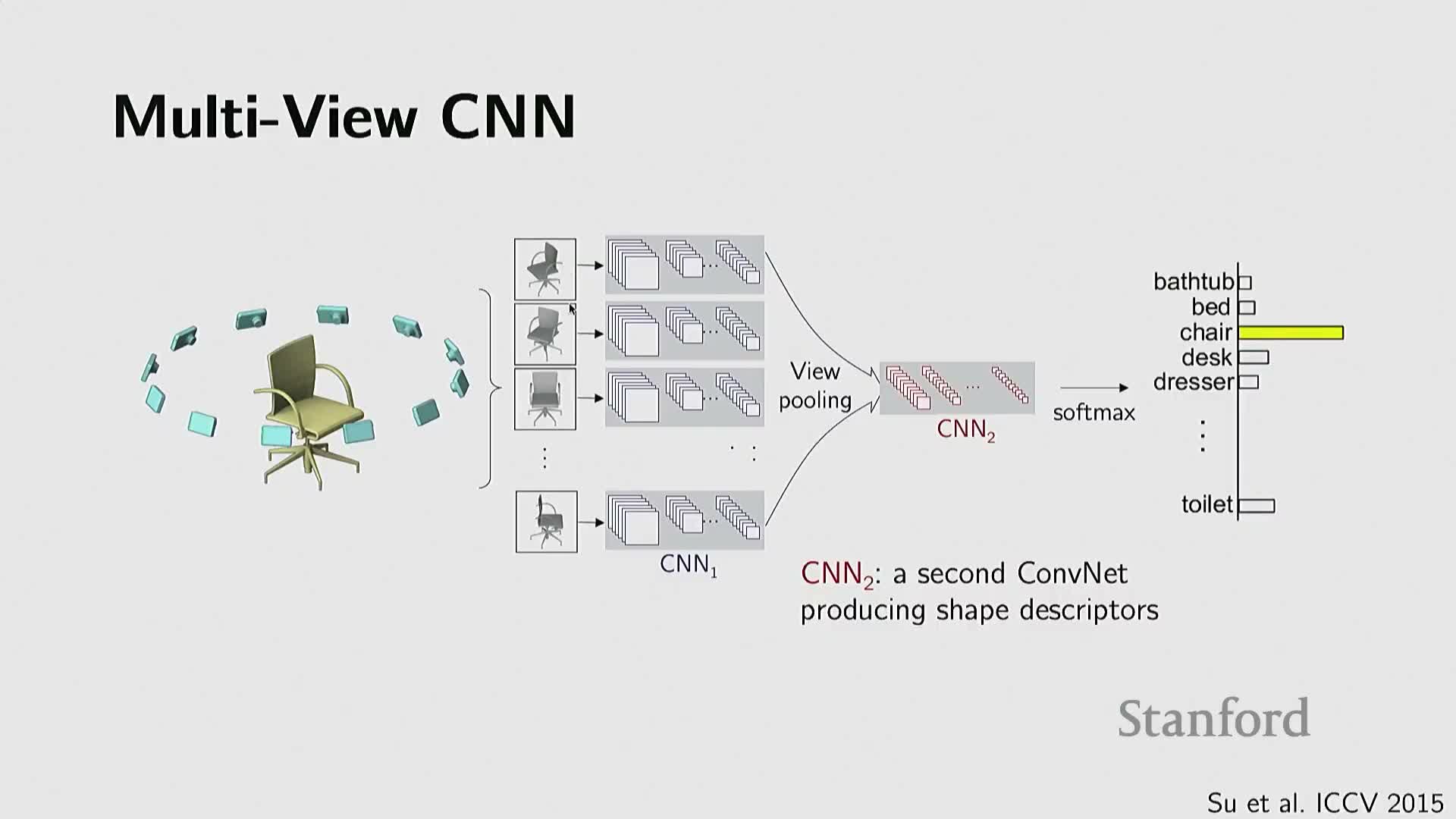

Rendering 3D models to multiple 2D views enables reuse of mature 2D image networks

A practical early pipeline converts 3D objects into multiple 2D renderings and applies established 2D convolutional networks to each view, followed by an aggregation or pooling stage to fuse multi-view features for tasks like classification.

- This view-based strategy leverages the maturity of 2D vision and large pretrained image models, bypassing irregular 3D data challenges by moving to a domain where models and data are abundant.

- It works well when renderings are clean and viewpoints cover discriminative facets of the object.

Limitations: the approach can degrade with noisy inputs, partial scans, or occlusions that produce low-quality views. Nevertheless, the view-based strategy provides a strong baseline when 2D pretrained priors are advantageous.

Volumetric generative models and hierarchical grids (octrees) scale 3D convolutional approaches

To reduce wasted computation in empty space, researchers extended volumetric neural methods with hierarchical structures such as octrees.

- Octrees and other sparse voxel schemes allow adaptive resolution: refine voxels near surfaces, coarsen in empty regions, and achieve higher effective resolution for the same memory budget compared with dense voxels.

- Volumetric generative networks and 3D convolutional architectures on octrees showed plausible synthesis and classification in early work.

Practical considerations: irregular data access and GPU implementation complexity motivated a parallel shift toward native 3D representations (point clouds, graph-based networks). Hierarchical voxel methods represent an important intermediate step that improved efficiency while preserving grid-convolution convenience.

PointNet family adapts neural architectures to unordered, sampled point clouds via symmetric aggregation

PointNet introduced a simple, effective paradigm for point-cloud processing: apply per-point embedding functions followed by a symmetric aggregation operator (e.g., max-pooling or sum) to produce a permutation-invariant global descriptor.

- This design specifically addresses two core invariances: permutation invariance (no canonical ordering of points) and sampling variability (density varies across surfaces).

- The architecture enables learning robust features directly from raw point coordinates and optional attributes.

Extensions and related components:

- Local neighborhood operators and graph neural networks built on k-NN graphs to capture locality.

- Point-based generative models for synthesis.

- Specialized loss functions for generation and reconstruction, such as Chamfer distance (nearest-neighbor set matching) and Earth Mover’s Distance (optimal transport bipartite matching), which provide differentiable measures between point sets.

PointNet-style architectures remain foundational due to their simplicity, invariance properties, and extensibility.

Atlas-style networks learn parametric mappings from low-dimensional parameter domains to 3D surfaces

Atlas-style approaches (e.g., AtlasNet) learn neural mappings from a low-dimensional parameter domain (a set of 2D patches or charts) to 3D coordinates, implementing a parametric surface with MLPs.

- Each learned patch maps sampled parameter coordinates (u,v) to 3D points; a collection of patches covers complex shapes.

- Benefits: produces smoother surfaces than raw point clouds, avoids dense volumetric grids, enables continuous surface generation, and supports refinement by sampling more parameter coordinates.

Limitations: patch stitching is required and representing arbitrary topology may demand many patches. Atlas-style models bridge classical parametric surface modeling and neural function approximation to generate compact, smooth geometry from latent representations.

Deep implicit functions and occupancy/SDF networks treat neural networks as continuous geometry queries

Starting around 2019, research converged on neural implicit functions: networks that map a 3D coordinate (x,y,z) to a scalar occupancy, signed distance, or density value, with the zero level set defining the surface.

- This recasts geometry modeling as a continuous function approximation problem.

- Advantages: arbitrary-resolution evaluation, analytic point-in-volume queries, and composition via arithmetic on function outputs.

- Networks can be trained from direct 3D supervision (occupancy or SDF samples) or indirectly via rendered projections.

Neural implicit representations provide compact continuous shape priors, integrate naturally with differentiable optimization and learning, and underpin many advances in neural rendering and geometry processing.

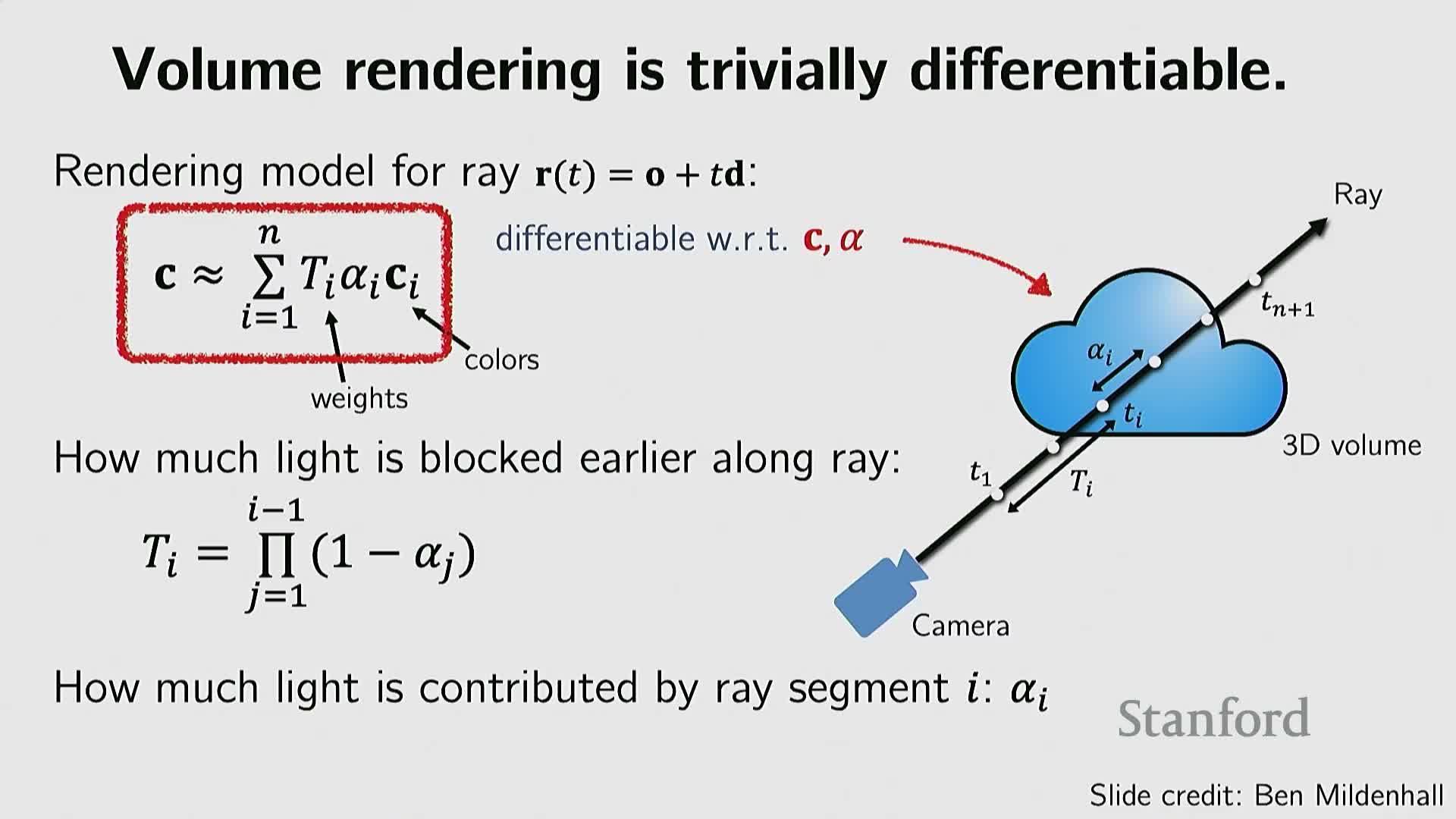

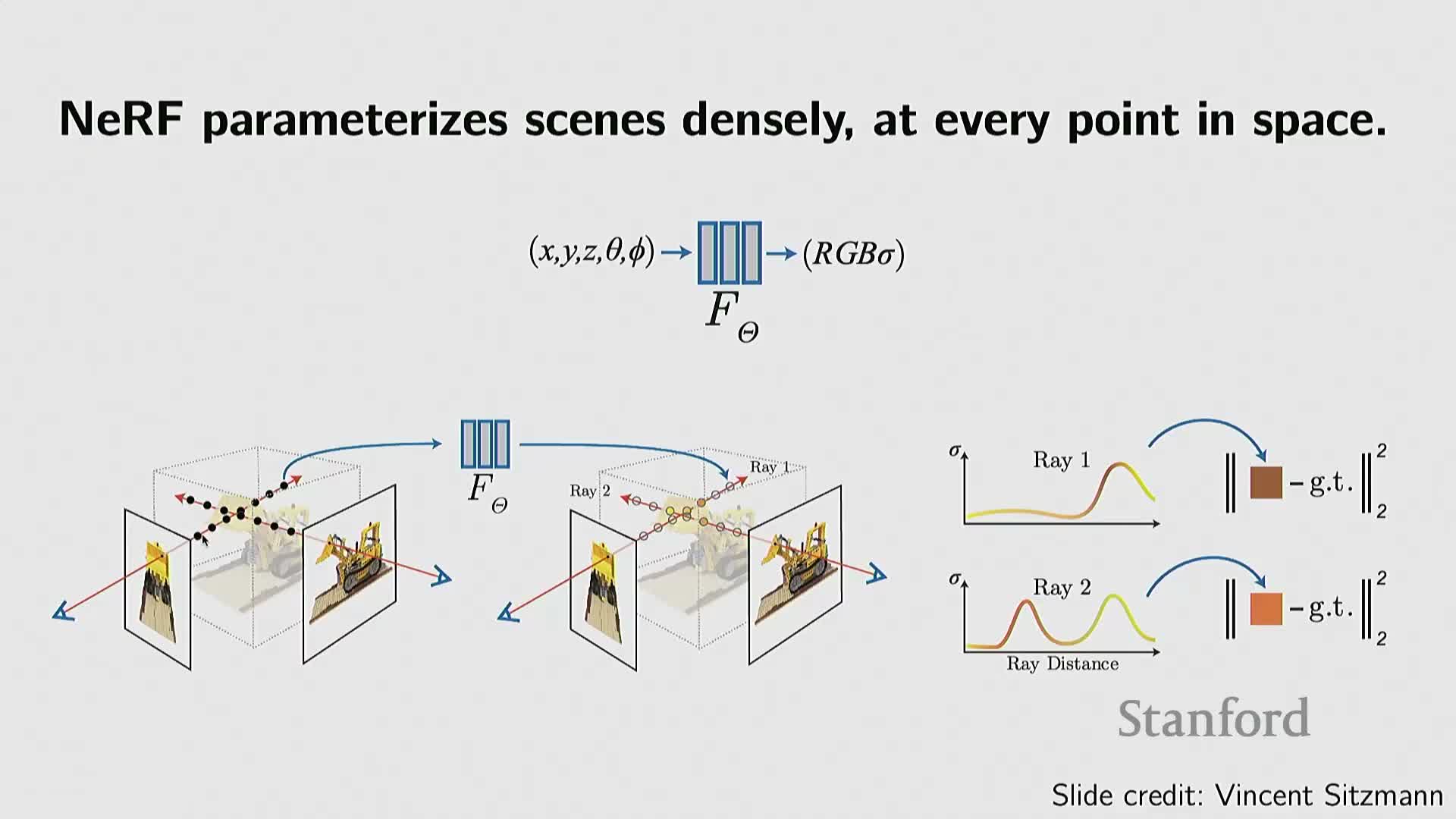

NeRF introduces neural radiance fields and differentiable volumetric rendering to learn appearance and geometry from images

Neural Radiance Fields (NeRF) extend neural implicit ideas to appearance by conditioning a network on 3D position and view direction, outputting per-point density and emitted radiance (color) that are integrated along camera rays using differentiable volume rendering.

- Because the rendering pipeline is differentiable, NeRF can be trained from multi-view 2D images without explicit 3D ground truth: per-ray color reconstruction losses backpropagate through sampled points and the implicit network to recover both shape and view-dependent appearance.

- NeRF simultaneously models geometry (via density fields) and appearance (view-dependent radiance), enabling photorealistic novel view synthesis from calibrated images.

Limitations: high computational cost due to dense ray sampling and frequent neural evaluations. NeRF marked a pivotal shift by leveraging abundant 2D image data and differentiable rendering to learn high-fidelity 3D scene representations.

Generative radiance fields and hybrid 3D+2D adversarial training produce controllable, realistic 3D object models

Generative frameworks combine implicit radiance-field representations with adversarial training to synthesize 3D scenes or objects whose rendered images are indistinguishable from real photographs.

- Architectures integrate latent vectors for geometry, appearance, and camera parameters.

- A neural radiance field serves as a generator mapping sampled 3D coordinates and directions to density and radiance, while 2D discriminators (or joint 2D/3D losses) evaluate rendered views to enforce image-space realism.

This hybrid training leverages the strengths of 2D adversarial learning and 3D continuous representations, enabling control over latent factors (shape, viewpoint, texture), and supporting tasks like texture transfer, latent interpolation, and conditional generation while benefiting from 2D image priors for appearance realism.

NeRF efficiency limitations motivated sparse, point-based rendering such as Gaussian splatting

NeRF-style volume rendering requires dense sampling along rays and many neural evaluations, which is computationally expensive because many samples lie in empty space or regions with negligible contribution.

A class of sparse, point-based approximations (e.g., Gaussian splatting) parameterizes a scene as a set of anisotropic Gaussian blobs or “splats” located where geometry and appearance concentrate.

- These representations focus computation on non-empty regions, enabling rasterization-style compositing at interactive framerates.

-

Gaussian splats and related methods substantially increase rendering throughput while often preserving comparable image quality by trading dense volumetric sampling for a compact, scene-adaptive point representation and efficient blending.

These hybrid approaches illustrate a broader trend of combining implicit representations with explicit, sparse primitives to improve runtime performance for view synthesis and real-time applications.

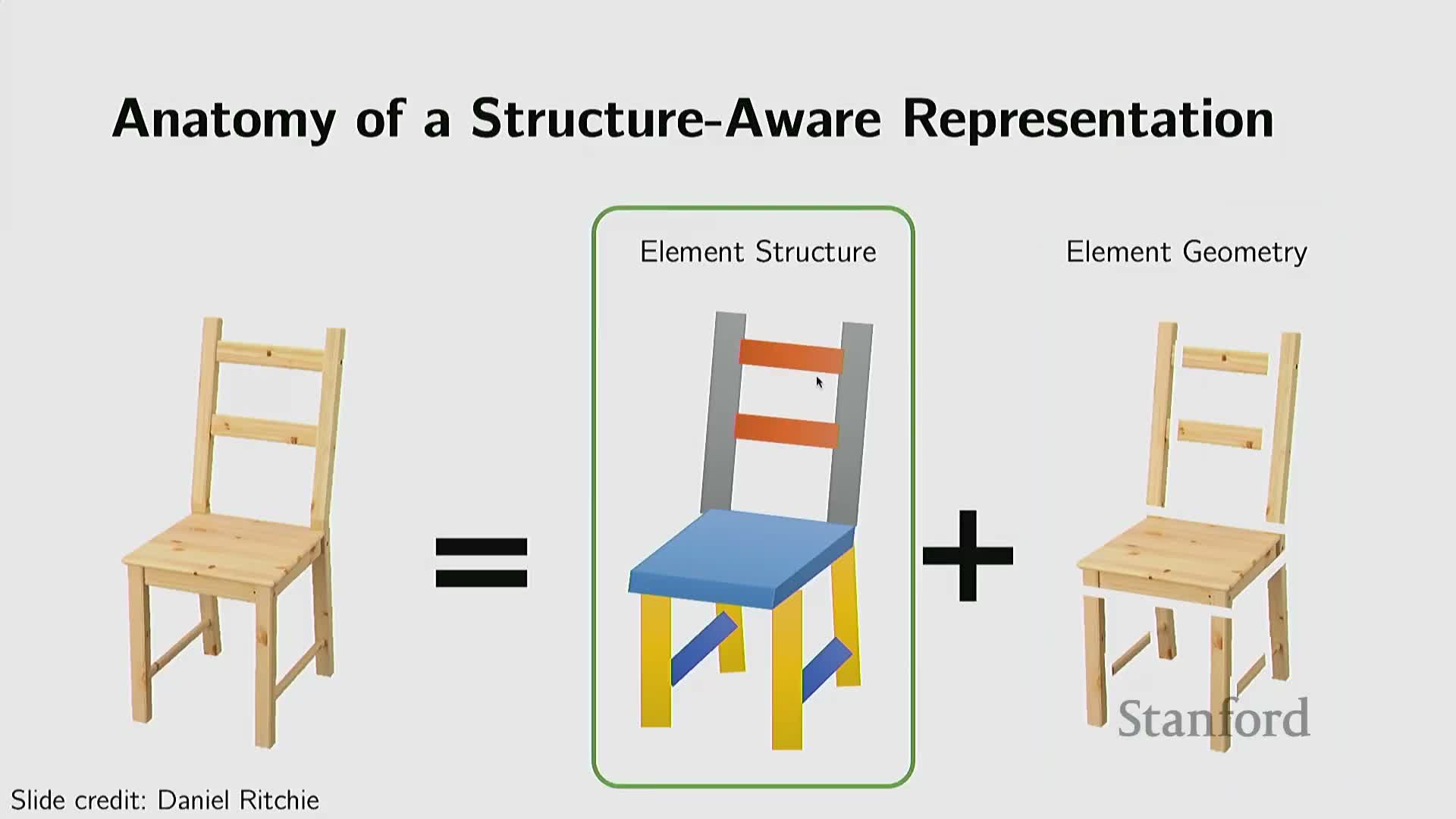

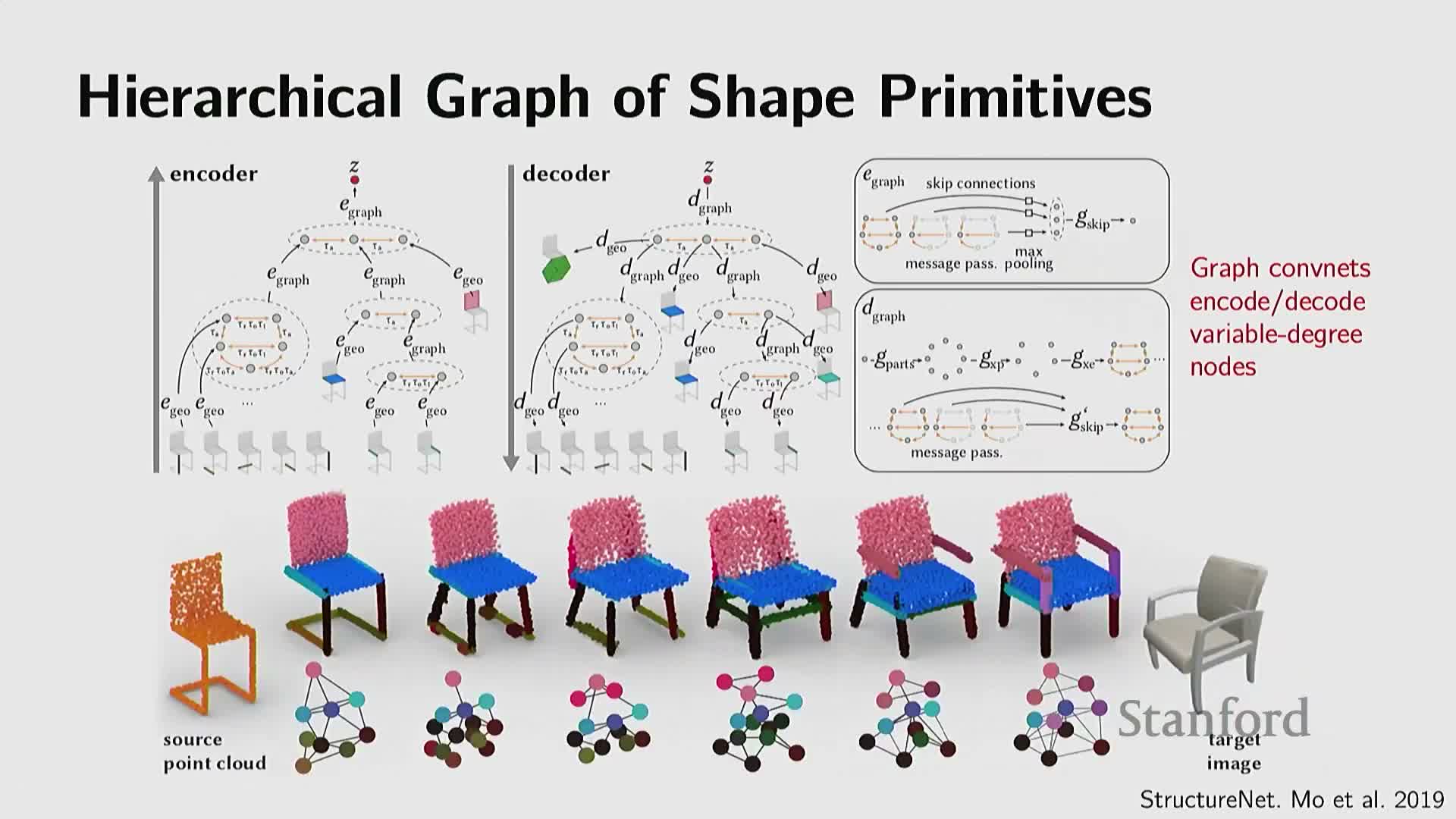

Modeling structural regularities, hierarchies and programmatic generation captures object semantics beyond local geometry

Beyond per-surface detail, object and scene modeling benefits from encoding higher-level structural regularities—symmetries, repeated parts, part hierarchies, and kinematic relationships—and from capturing constraints among parts (e.g., symmetry of chair legs or mobility of laptop lids).

Methods encode objects as:

- Collections of parts with relational graphs,

- Hierarchical encoders/decoders, or

-

Programmatic representations expressing repetition and parametric rules.

Generative models that respect semantic and functional constraints can produce structured outputs. Recent trends explore learned or language-conditioned program generators that produce procedural shape descriptions, combining high-level semantics from large language or multimodal models with low-level geometric refinement by implicit or parametric decoders.

This structural and programmatic perspective links semantic reasoning, manufacturable geometry, and controllable generative modeling for complex, compositional 3D assets.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: