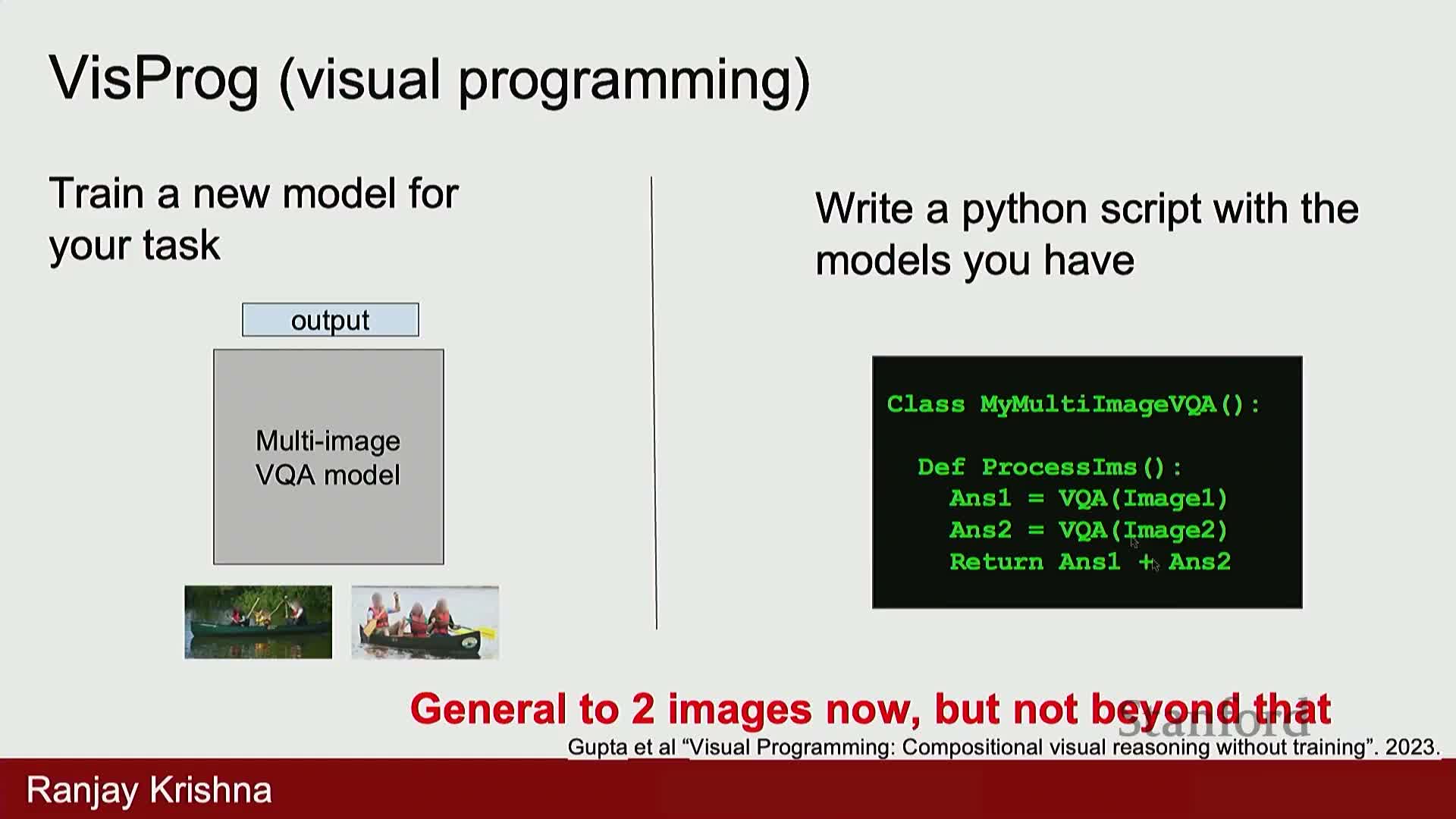

Stanford CS231N Deep Learning for Computer Vision | Spring 2025 | Lecture 16- Vision and Language

- This session opens with an overview of multimodal foundation models and the lecturer’s research context

- Foundation models are large pre-trained systems intended to be adapted to many downstream tasks via minimal task-specific data

- Contrastive self-supervised objectives extend naturally to image–text pretraining to align image and text embeddings

- CLIP trains joint image and text encoders with contrastive pretraining on large collections of image–text pairs

- Zero-shot classification with CLIP uses text encodings of class descriptions as nearest-neighbor prototypes

- Scale, model architecture and data diversity explain CLIP’s strong generalization, and captioning objectives further improve features

- CLIP offers fast embedding-based retrieval and open-vocabulary prediction but suffers from batch-scale sensitivity and compositional limitations

- Multimodal language models embed visual tokens into autoregressive language architectures to enable grounded text generation

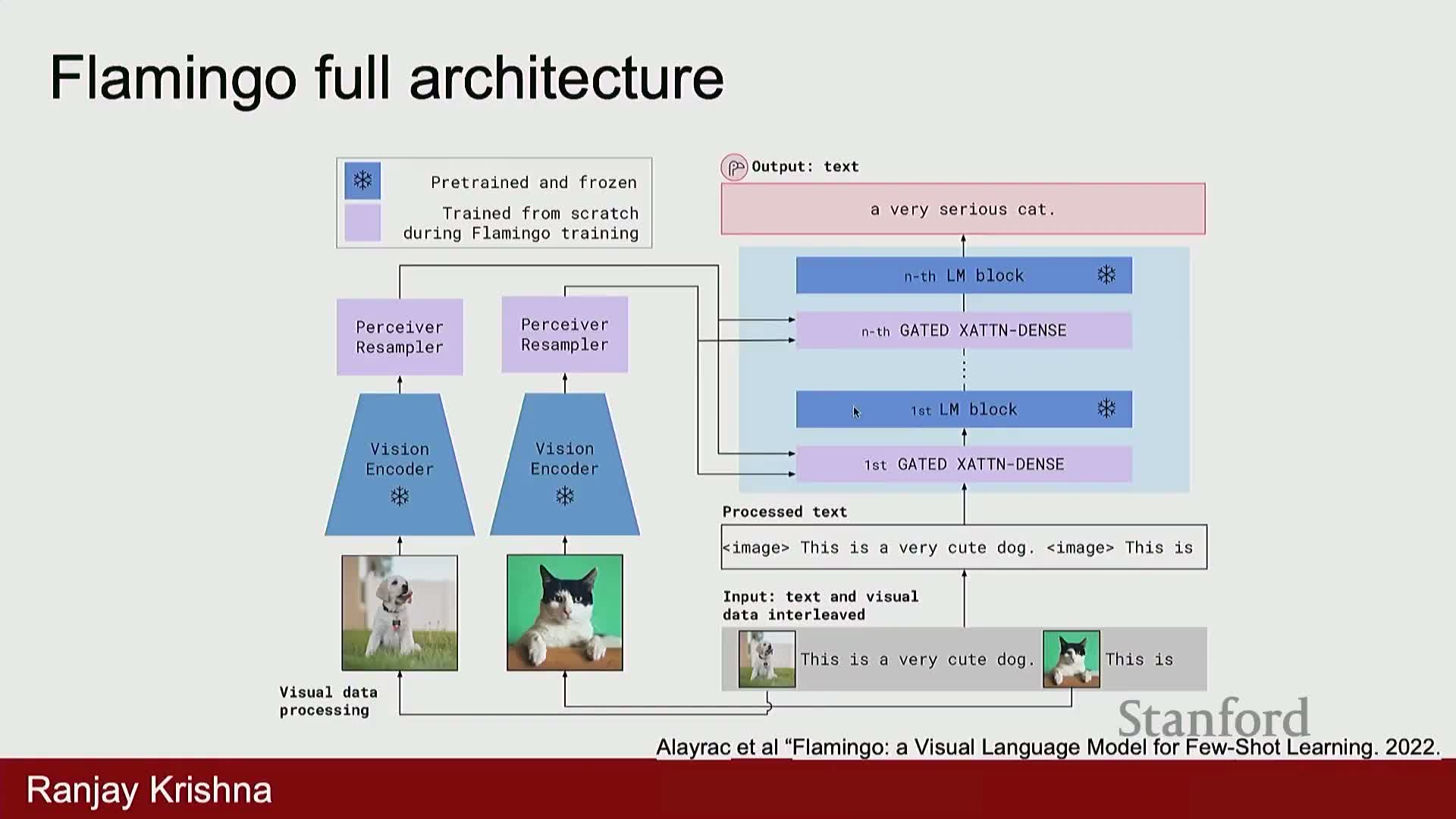

- Flamingo injects vision features into every layer of a frozen LLM using gated cross-attention and a perceiver sampler

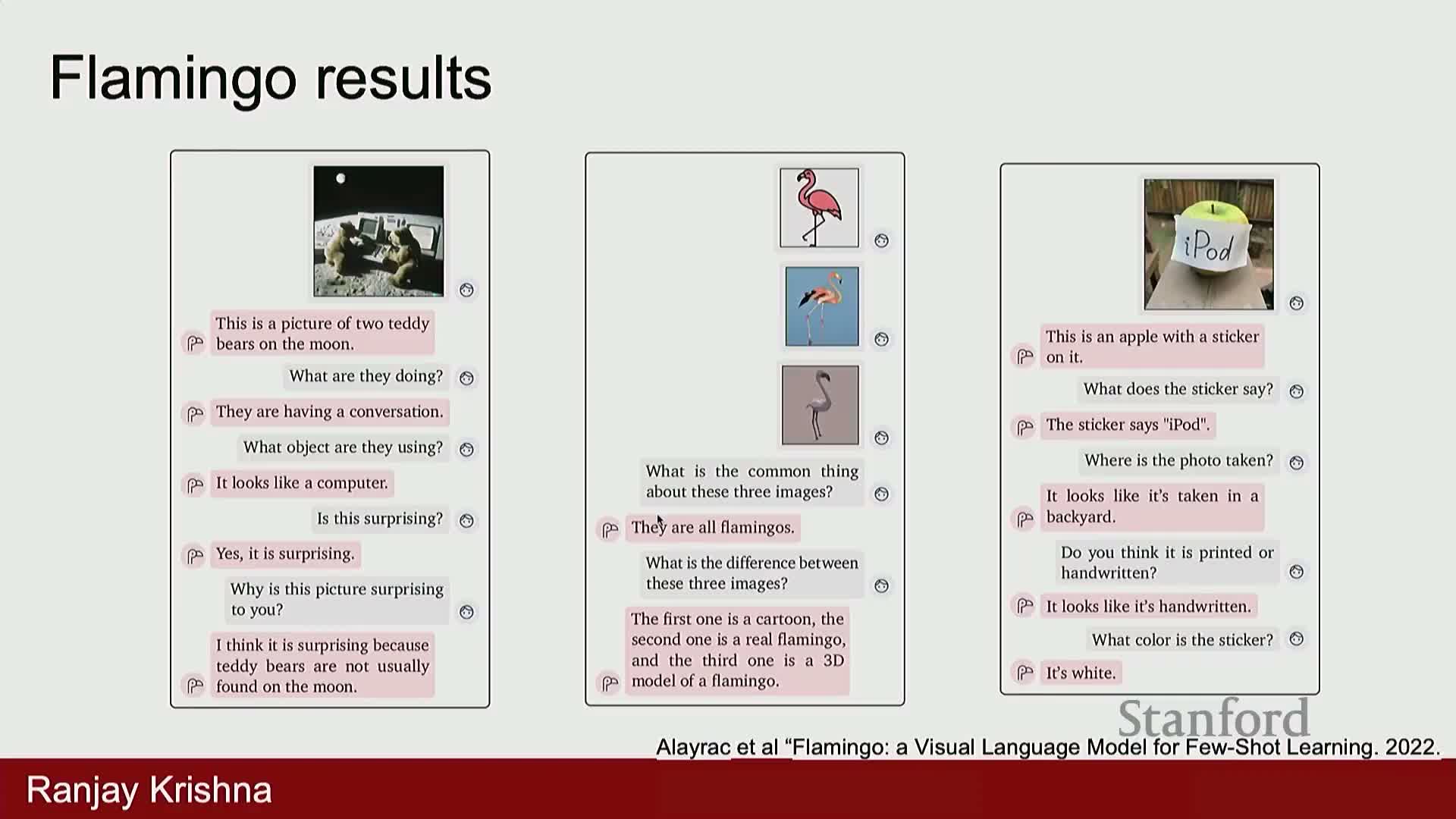

- Flamingo is trained on interleaved image–text sequences with masking to support image-specific autoregressive generation, enabling in-context multimodal reasoning

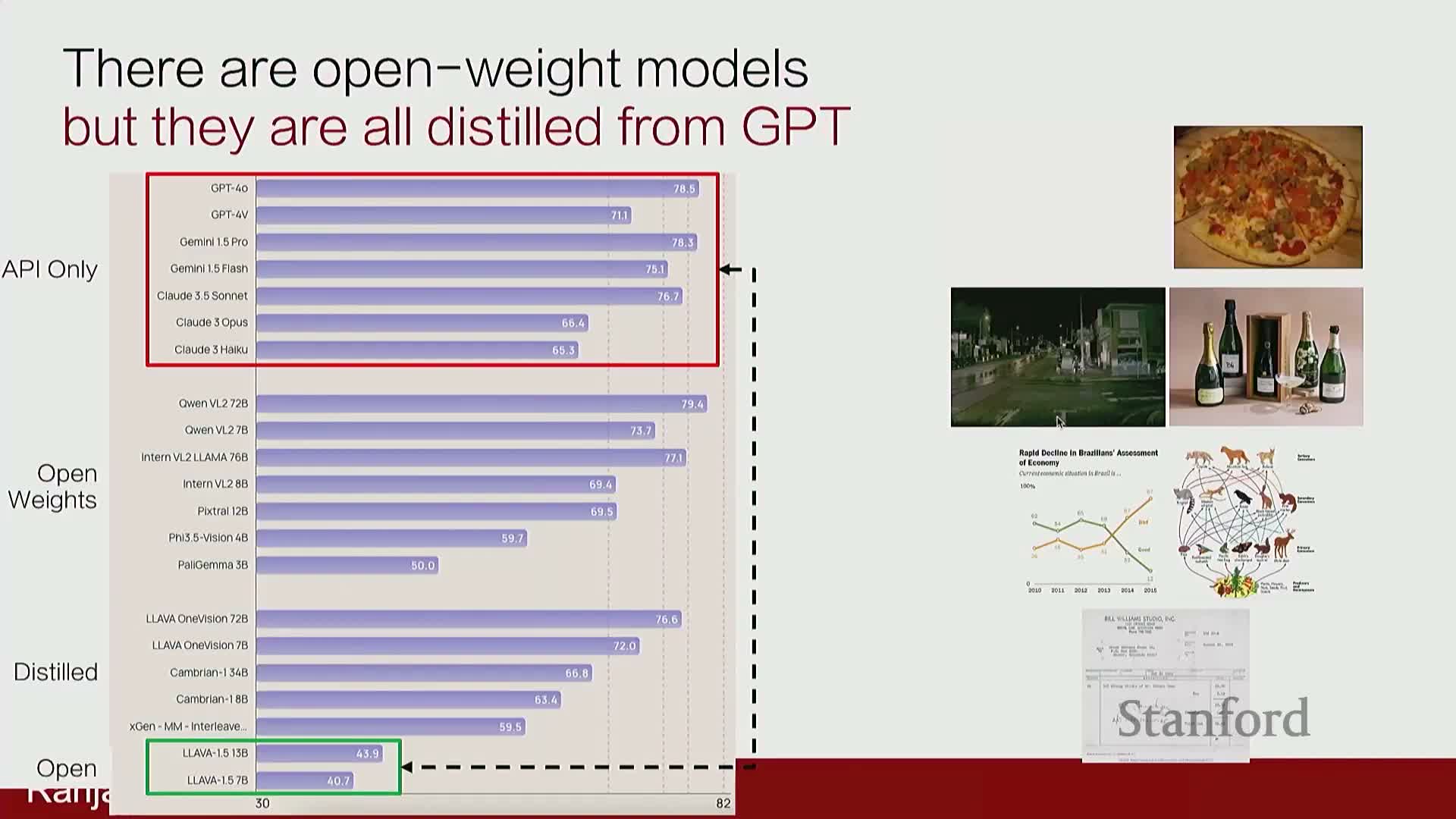

- Commercial multimodal APIs achieved high benchmark performance while the open-source community lagged, motivating reproducible open-source models

- Momo demonstrates that curated, dense, grounded visual supervision and pointing mechanisms yield strong open-source multimodal performance

- SAM (Segment Anything Model) provides a promptable segmentation foundation by encoding images and user prompts and producing multiple mask hypotheses

- Building robust segmentation and multimodal foundations requires massive task-focused annotation and iterative human-in-the-loop dataset expansion

This session opens with an overview of multimodal foundation models and the lecturer’s research context

The session frames multimodal foundation models at the intersection of computer vision, natural language processing, robotics and HCI—positioning the topic as inherently cross-disciplinary.

It outlines the lecture scope, including:

-

Image and language foundation models

-

Multimodal integration and generation of diverse output modalities (text, masks, images)

-

Model chaining to compose capabilities into pipelines

The overview situates the material within recent advances such as:

-

Self-supervised pretraining

-

Large-scale data collection

-

Cross-modal adaptation

Concrete examples highlighted to orient the audience include CLIP, CoCa, Flamingo, LLaVA, and chainable pipelines—preparing listeners for detailed algorithmic descriptions, architectural motifs, and data collection practices presented later.

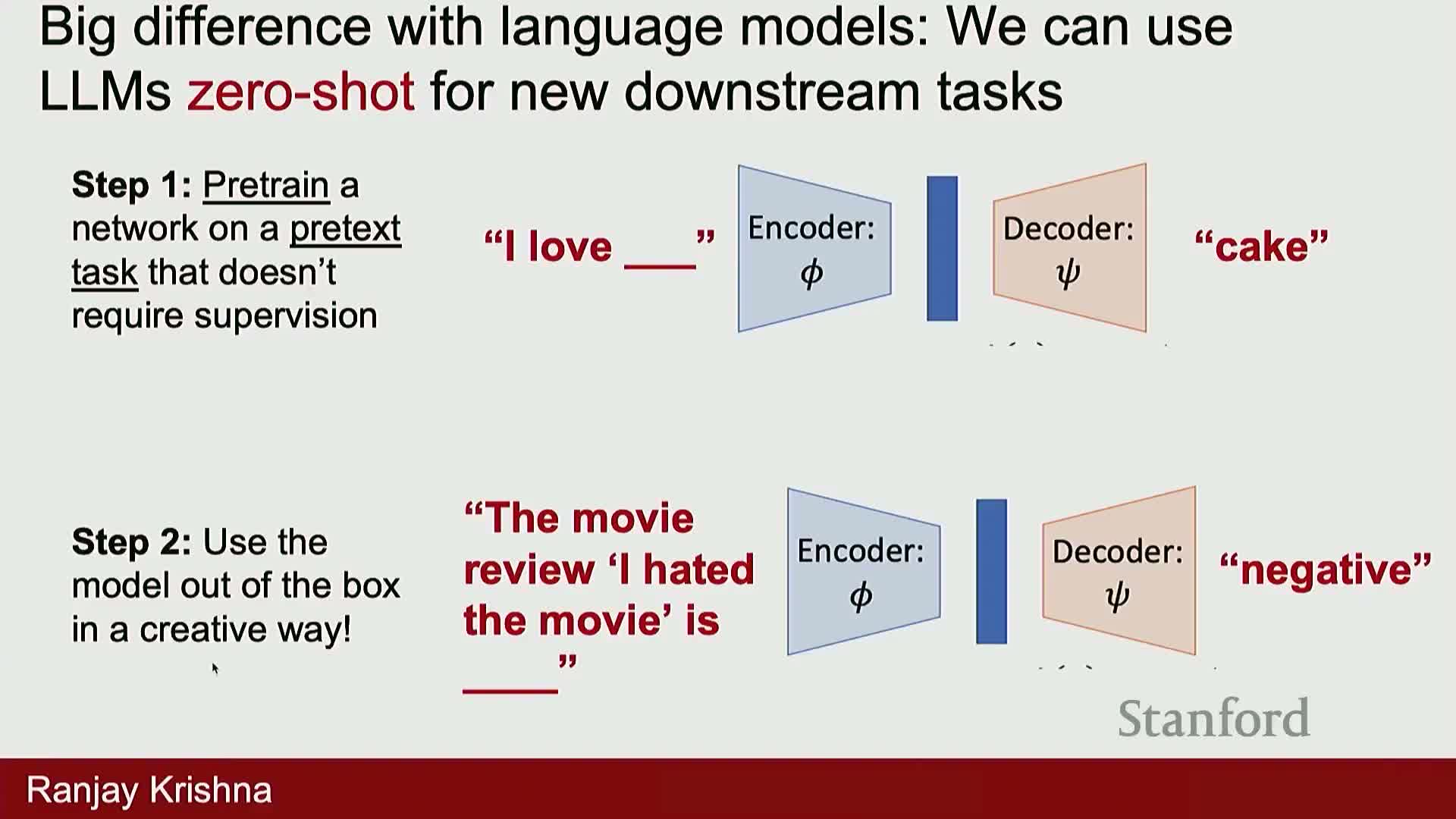

Foundation models are large pre-trained systems intended to be adapted to many downstream tasks via minimal task-specific data

Foundation model — a large-scale model pre-trained on diverse data and objectives so it produces representations or behaviors broadly useful across many tasks.

Key aspects of the pretraining and adaptation lifecycle:

- Pretraining uses abundant raw data and often self-supervised or weakly supervised objectives.

- The result is a high-capacity model that typically requires little task-specific data for adaptation.

- Common language examples: ELMo, BERT, and autoregressive models such as GPT.

- The same principles apply to vision and vision–language models, yielding general-purpose encoders and decoders.

Core properties of foundation models:

-

Large parameter counts and scalable architectures (e.g., transformers).

-

Vast training corpora (often internet-scale).

-

Generalized pretraining objectives that transfer across tasks.

- Flexible adaptation via fine-tuning, few-shot, or zero-shot pipelines.

The discussion emphasizes that foundation models trade narrow specialization for broad adaptability, usually relying on web-scale data and architectures that scale with capacity and compute.

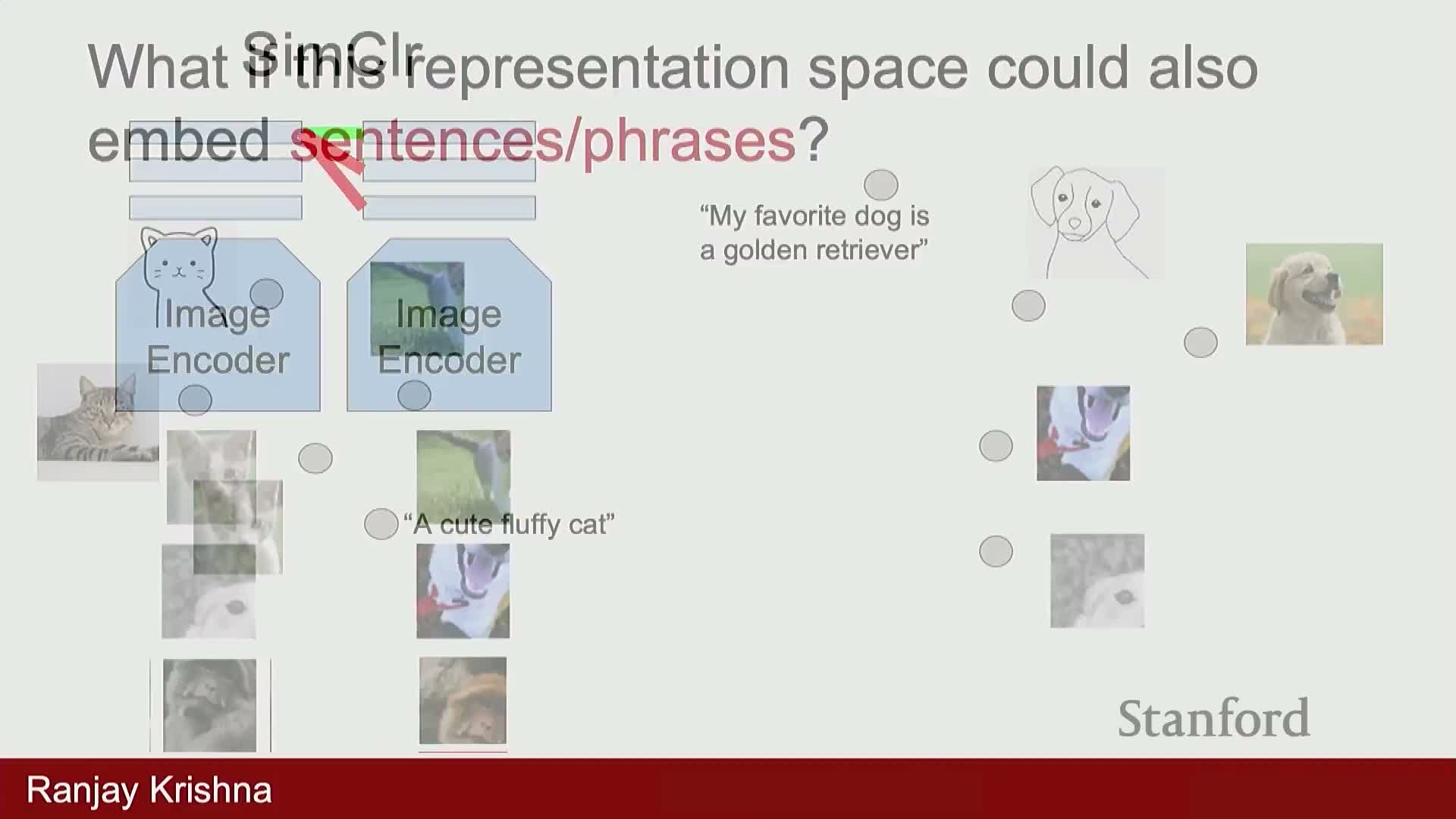

Contrastive self-supervised objectives extend naturally to image–text pretraining to align image and text embeddings

Contrastive self-supervised learning trains encoders to pull together representations of related views and push apart unrelated ones, producing generalizable embeddings without manual labels.

Extending contrastive learning to multimodal data:

- Use paired image and text encoders.

- Maximize similarity between matching image–text pairs while minimizing similarity with other pairs in the same minibatch.

- Apply a symmetric contrastive loss (images→text and text→images) to enforce a shared embedding space where semantic proximity corresponds to cross-modal relevance.

Practical considerations and implementation details:

- Large batches provide diverse negatives; formulations include mini-batch cross-entropy or InfoNCE loss.

- Scalable encoder choices: ResNet or ViT for images, transformer-based encoders for text.

Outcomes: the aligned embedding space enables retrieval, zero-shot transfer, and downstream adaptation by leveraging abundant image–text pairs harvested from the web.

CLIP trains joint image and text encoders with contrastive pretraining on large collections of image–text pairs

CLIP pairs an image encoder and a text encoder and is trained with a symmetric contrastive loss across image–text pairs so each image embedding is close to its caption and far from other captions in the minibatch.

Important training and architectural points:

- Training requires massive image–text corpora and benefits from transformer-based vision encoders (e.g., ViT) together with reasonably sized text transformers.

-

Model scale and dataset size strongly influence representation quality.

Primary adaptation patterns after pretraining:

-

Linear probing — add and train a simple classifier on top of frozen features.

-

Zero-shot classification via text prompts — embed candidate class descriptions and perform nearest-neighbor retrieval in embedding space.

Scaling notes: the training process is straightforward to scale but depends on sufficient negatives in each batch to learn fine-grained distinctions; otherwise the representations remain coarse.

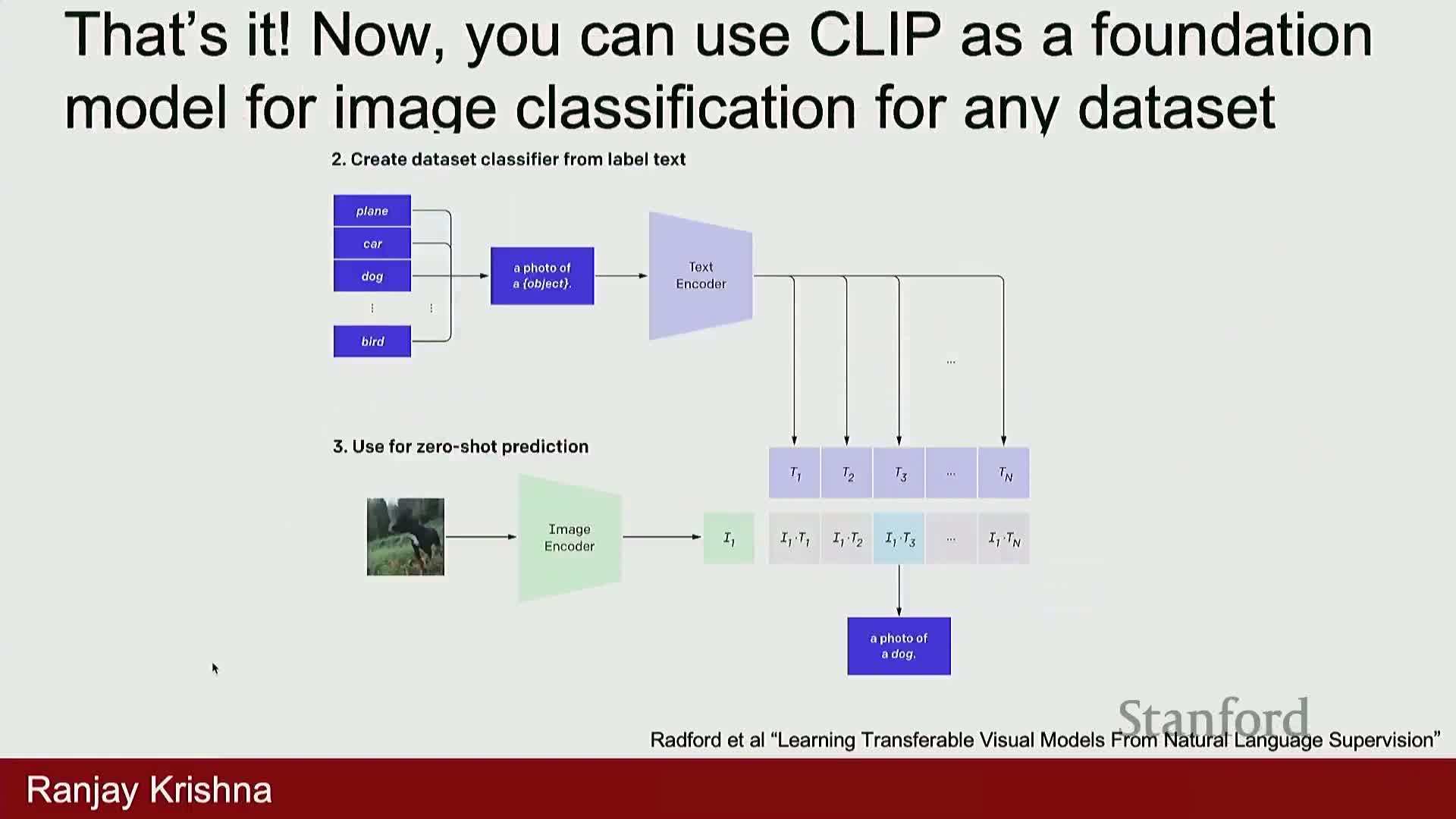

Zero-shot classification with CLIP uses text encodings of class descriptions as nearest-neighbor prototypes

Zero-shot CLIP classification constructs a class prototype by encoding a text description for each target label and comparing image embeddings to these prototypes (cosine similarity or dot product).

Typical workflow (numbered):

- Encode a descriptive text prompt for each class (avoid isolated tokens).

- Compute the text embeddings to form class prototypes.

- Compare image embeddings to prototypes and predict via nearest-neighbor in the shared space.

Practical prompt engineering tips:

- Single-word labels often underperform because CLIP was trained on phrases rather than tokens.

- Use descriptive phrases like “a photo of a dog” to improve alignment with image-space semantics.

- To reduce sensitivity to phrasing, generate many prompt variants per class (e.g., “a drawing of a dog”, “a photo of a dog”, …), compute their embeddings, and average them to produce a robust prototype.

This retrieval-based approach enables rapid adaptation to arbitrary label sets without gradient updates or labeled examples.

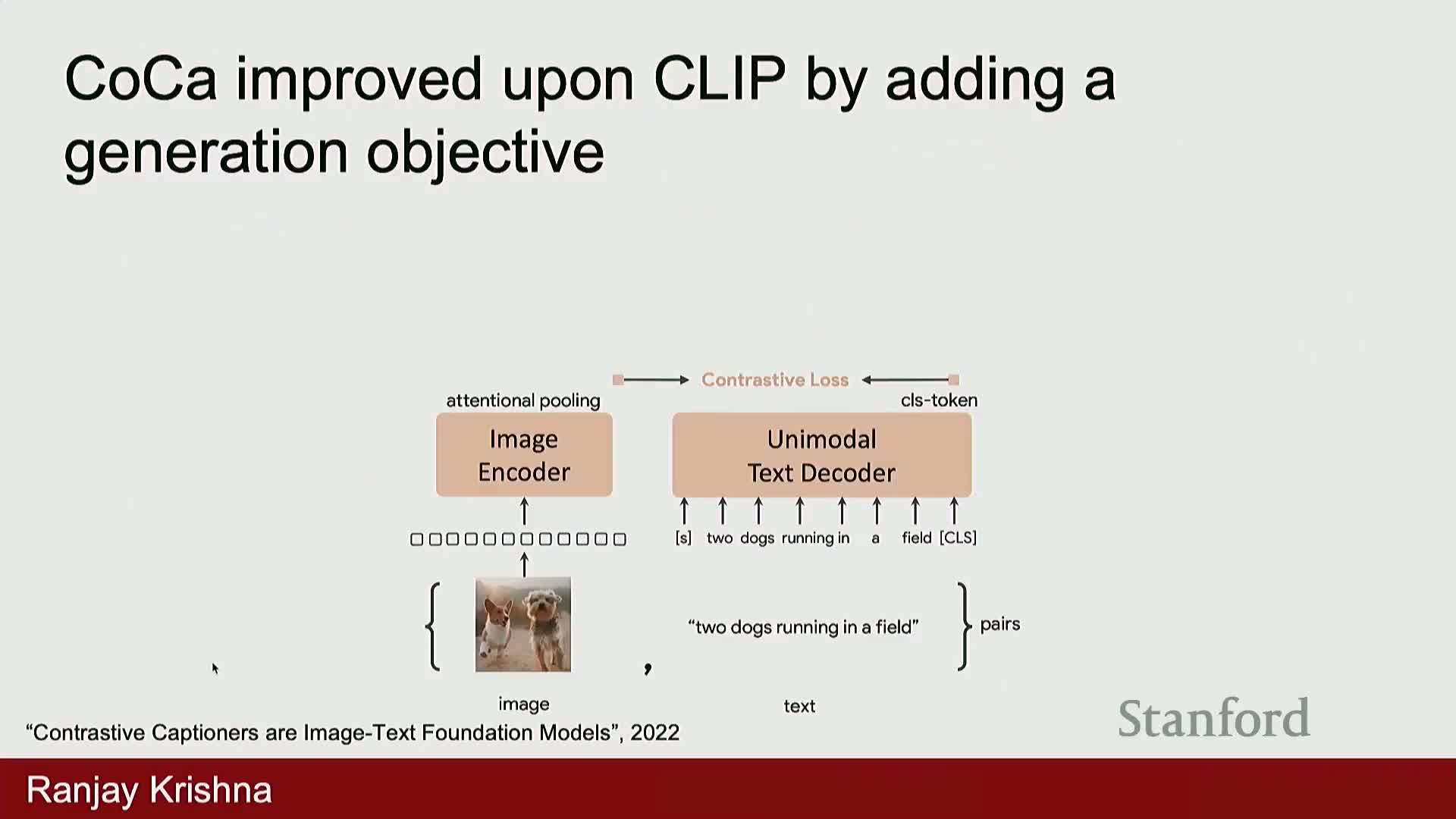

Scale, model architecture and data diversity explain CLIP’s strong generalization, and captioning objectives further improve features

CLIP’s empirical strength stems from three interacting factors:

- A transformer-based vision encoder that scales well (e.g., shifts from ResNet to ViT).

-

Large parameter counts that increase representation expressiveness.

-

Massive image–text datasets scraped from the web, providing diverse supervisory signals beyond curated datasets like ImageNet.

Richer objectives improve descriptive power:

- Extending contrastive alignment with generative captioning decoders (as in CoCa) yields denser supervision because producing full captions forces the model to learn attributes like color, shape and spatial relations.

- Joint contrastive + captioning objectives encourage more descriptive image representations and improve downstream performance.

Together, architectural advances, scale, and richer objectives yield significant gains on both in-domain and out-of-domain benchmarks.

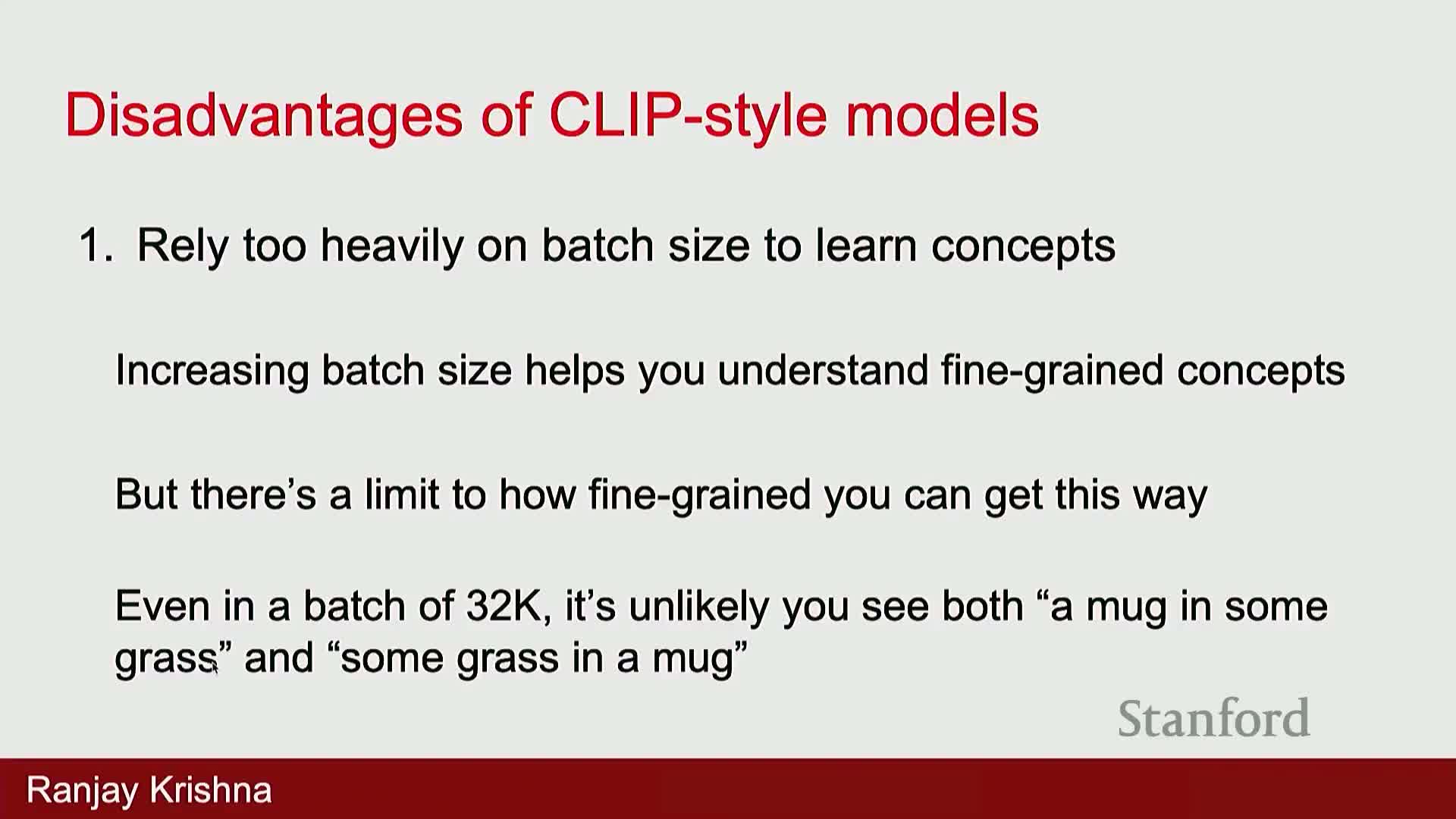

CLIP offers fast embedding-based retrieval and open-vocabulary prediction but suffers from batch-scale sensitivity and compositional limitations

Advantages of CLIP:

- Simple, scalable contrastive training objective.

-

Rapid inference for retrieval via precomputed embeddings.

-

Open-vocabulary operation through text prompts, enabling zero-shot classification and flexible search.

Limitations and failure modes:

- Contrastive training is sensitive to minibatch composition: large batch sizes or many negatives are needed to expose hard negatives, which can require substantial compute.

- Insufficient negatives lead to coarse, high-level representations that miss fine-grained distinctions.

- CLIP struggles with compositionality and relational reasoning (e.g., distinguishing “mug in grass” from “grass in mug”).

-

Image-level captions lack grounding and structured spatial supervision, motivating research in data filtering, curated supervision, and additional objectives to capture fine-grained and grounded relations.

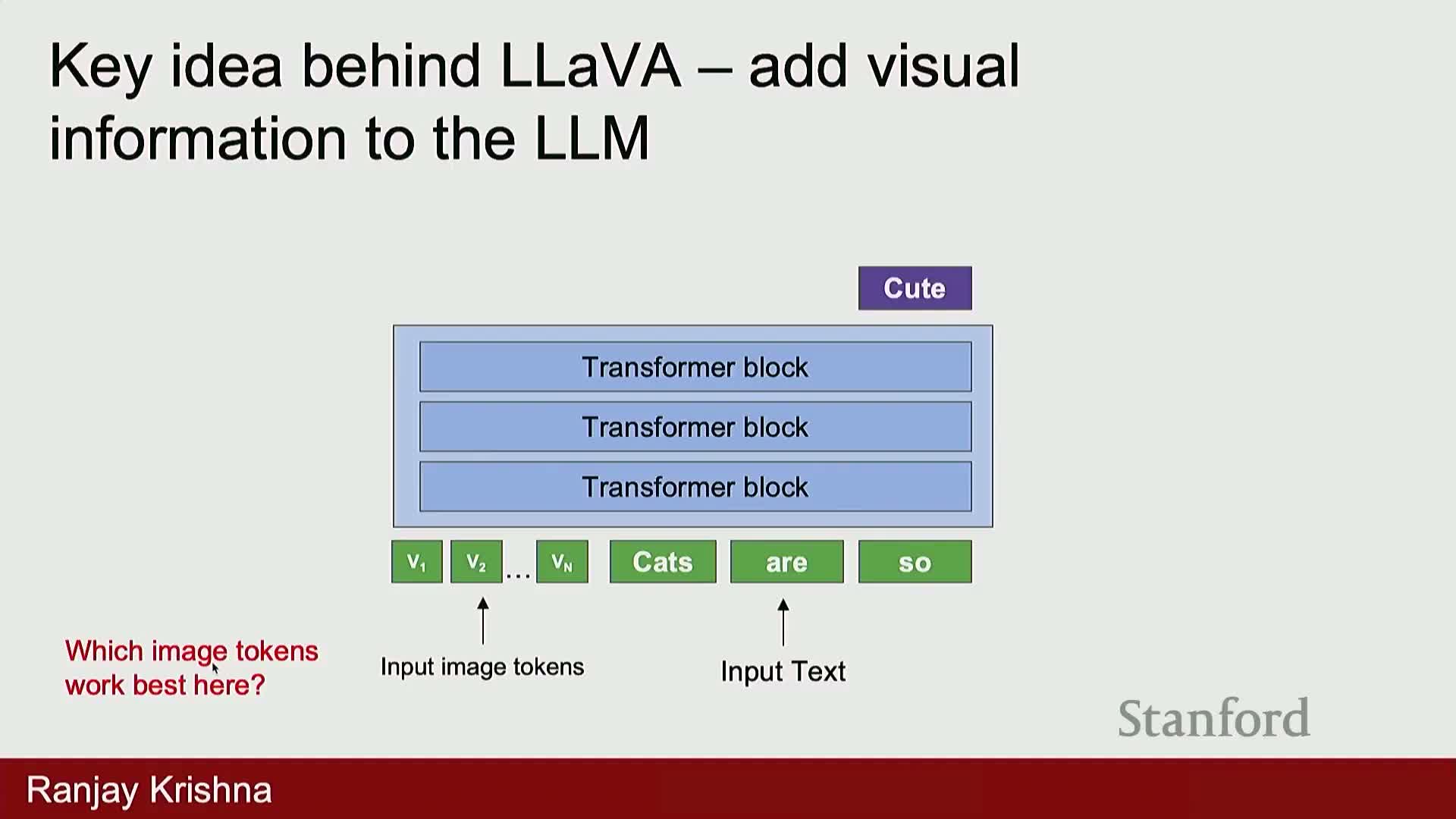

Multimodal language models embed visual tokens into autoregressive language architectures to enable grounded text generation

Multimodal language models extend autoregressive LLMs by providing visual context as additional tokens that the language model conditions on while predicting the next token.

Key components and process:

- Visual inputs are tokenized using a pre-trained image encoder (often CLIP) and then transformed via a learned connector to match the LLM input space.

- The penultimate layer outputs of vision transformers are commonly used because they retain spatial detail useful for reasoning.

- During training, the LLM learns to autoregressively generate text conditioned on both prior textual context and the injected visual tokens.

Capabilities enabled:

-

Image captioning, visual question answering, and multi-turn visual dialogue.

- Leverages pretrained LLM generalization and reasoning while adding a learned interface that translates spatial visual features into the LLM token stream.

Flamingo injects vision features into every layer of a frozen LLM using gated cross-attention and a perceiver sampler

Flamingo fuses vision and language by inserting a small cross-attention module into each LLM transformer layer and by mapping variable-sized vision outputs to a fixed-size token set via a perceiver-style sampler.

Design characteristics:

- Most base weights (LLM and vision backbone) remain frozen; training primarily updates the cross-attention layers and the sampler.

- The sampler attends to image patches and selects a compact set of tokens for the LLM.

- Per-layer cross-attention looks up image features, applies gating nonlinearities (e.g., tanh and element-wise gating) and residual connections to decide which visual cues are relevant during language generation.

Benefits: this design lets the LLM selectively attend to visual evidence at multiple depths, improving multi-turn visual reasoning while keeping the number of trainable parameters small and preserving pre-trained language capabilities.

Flamingo is trained on interleaved image–text sequences with masking to support image-specific autoregressive generation, enabling in-context multimodal reasoning

Flamingo’s training corpus and masking scheme enable long-range multimodal context without cross-image leakage.

How the training setup works (numbered):

- Concatenate many image–text pairs into long interleaved sequences (image, caption, image, caption, …).

- Apply a masking scheme so that when the model generates text for one image it only attends to the corresponding image tokens.

- Train with an autoregressive language modeling objective: each caption is completed conditioned on its paired image tokens and prior textual context.

Why this matters:

- Masking prevents leakage from unrelated image features while still allowing the model to learn long-range multimodal context.

- Enables in-context multimodal learning: providing example image/question–answer pairs in the prompt yields few-shot generalization to new visual tasks and supports multi-turn visual dialogue without task-specific fine-tuning.

Empirically, Flamingo produced substantial zero- and few-shot improvements across diverse visual reasoning and comprehension benchmarks, shifting vision evaluation toward question-answering style tasks.

Commercial multimodal APIs achieved high benchmark performance while the open-source community lagged, motivating reproducible open-source models

Industry multimodal systems such as GPT-4V, Gemini, and Claude variants demonstrated large gains on visual understanding benchmarks and provided convenient APIs—creating a performance gap between closed-source capabilities and publicly reproducible models.

Consequences and community responses:

- Distillations of closed models produced some open releases but often omit original pretraining recipes and data, hindering exact reproduction.

- This reproducibility gap motivated the development of fully open pipelines that publish weights, data and training code so researchers can reproduce and extend leading multimodal behaviors without dependence on proprietary services.

- Open-source high-performing multimodal models enable independent evaluation, domain specialization, and community-driven improvements in data curation and model design.

Momo demonstrates that curated, dense, grounded visual supervision and pointing mechanisms yield strong open-source multimodal performance

Momo is an open-source multimodal model family that emphasizes grounding decisions in image pixels and dense human-elicited annotations rather than relying solely on incidental internet captions.

Key design features:

- A pointing mechanism that provides spatial evidence for answers (e.g., indicating which pixels correspond to counted objects).

- Training on a curated dataset of densely annotated image–text pairs capturing position, material, shape and other attributes.

- A compact connector that maps vision features into a language model.

Trade-offs and outcomes:

- Despite using orders of magnitude less raw image–text data than some closed models, Momo attains competitive human-preference evaluations via careful dataset design and task-focused annotation elicitation.

- Grounding outputs in pixels reduces certain hallucinations and enables downstream chaining for segmentation and robotics applications.

- Demonstrates that annotation quality and task-specific supervision can compensate for raw dataset scale.

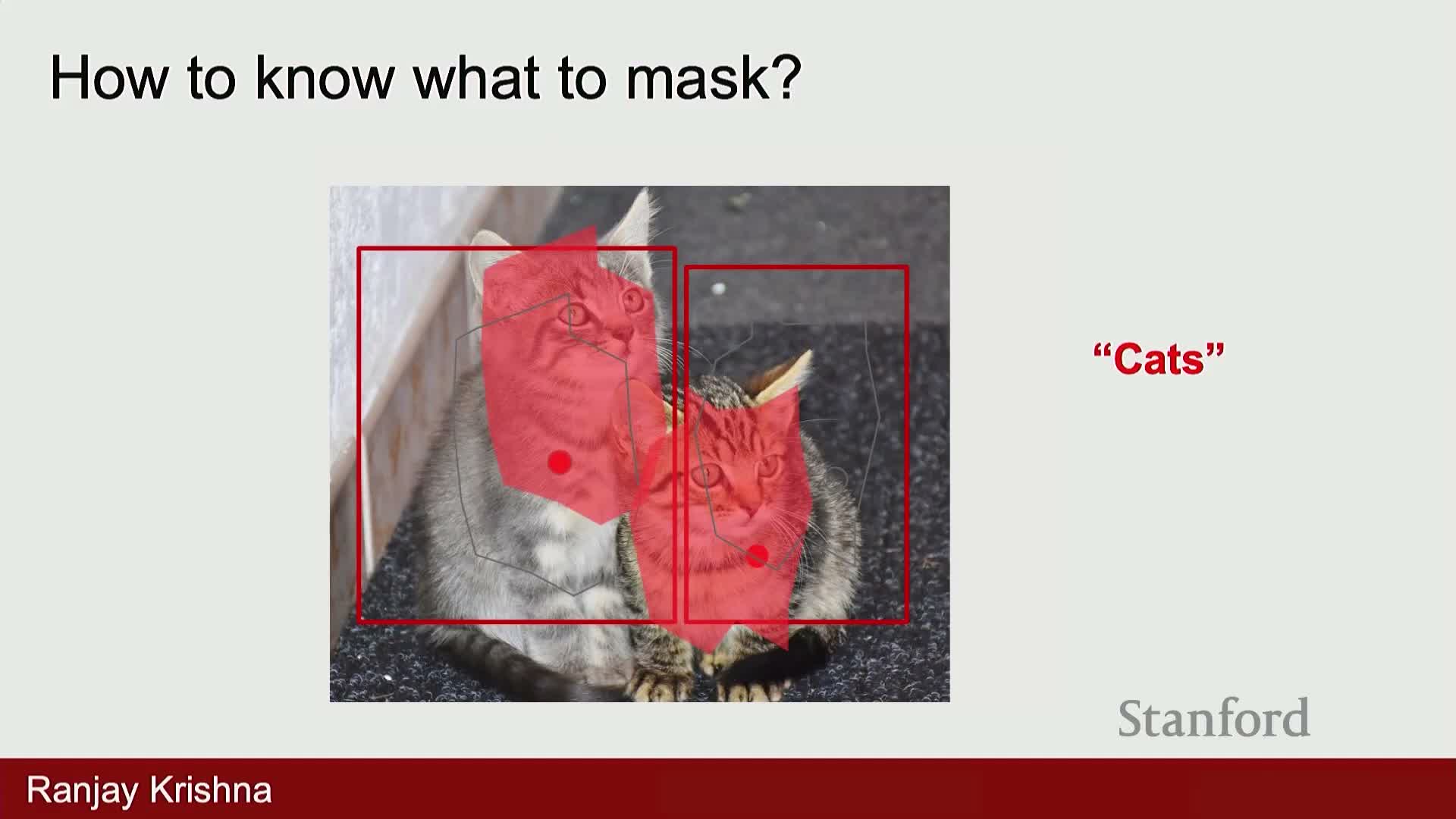

SAM (Segment Anything Model) provides a promptable segmentation foundation by encoding images and user prompts and producing multiple mask hypotheses

SAM frames segmentation as a promptable interface: an image encoder produces dense visual features, a prompt encoder ingests user signals (points, boxes, text, or other modalities), and a lightweight decoder outputs one or more segmentation masks for the requested region.

Architectural and interaction highlights:

- The prompt encoder normalizes diverse input modalities into a shared prompt representation, enabling interactive workflows where a user supplies a point or box and the model returns candidate masks.

- To handle ambiguity (e.g., a point on a multi-part object), SAM produces multiple masks at different granularities and during training selects the best match against ground truth—avoiding penalization of reasonable alternative segmentations.

- Architecturally SAM decouples heavy visual encoding from a small, efficient mask decoder, supporting prompt-conditioned inference for open-vocabulary object selection and interactive image editing.

Building robust segmentation and multimodal foundations requires massive task-focused annotation and iterative human-in-the-loop dataset expansion

High-quality segmentation foundations require dense mask datasets that cover many categories, contexts and granularities—prior corpora were inadequate in scale and diversity.

Data-collection and annotation strategy (numbered iterative cycle):

- Seed annotations using human annotators.

- Train models on seed data to propose segments.

- Have annotators correct and refine model proposals.

- Repeat the cycle to multiply annotation throughput and improve model generalization.

Annotation design priorities:

- Produce dense, descriptive labels that capture positional, material and relational attributes often absent from web captions.

- Use elicitation strategies (e.g., spoken rather than typed responses) to reduce stereotyped descriptions and surface latent visual knowledge.

Impact: the resulting high-quality, diverse mask collections underpin generalized segmentation models like SAM, enabling downstream tasks such as interactive editing, instance-level retrieval and compositional masking.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: