Stanford CS231N Deep Learning for Computer Vision | Spring 2025 | Lecture 17- Robot Learning

- Introduction to robot learning as an interdisciplinary research area

- Contrast between supervised/self-supervised learning and robot learning

- Robot learning emphasizes sequential actions that influence environment evolution and reward accumulation

- Problem formulation for embodied agents: goals, states, actions, and rewards

- Instantiations of robot learning across domains (control, locomotion, games, language-conditioned agents, manipulation)

- Reward specification requires careful design and can be application specific

- Robot perception is embodied, active, and situated and requires multisensory integration

- Reinforcement learning enables learning via trial-and-error interactions but differs fundamentally from supervised learning

- Value-based RL and large-scale policy learning demonstrate emergent strategies in simulated domains

- Reinforcement learning succeeds in locomotion and faces challenges in manipulation in real world

- Model-based learning and planning use learned forward models for predictive control and trajectory optimization

- State representations for learned dynamics range from pixels to keypoints to particle-based models and dictate model accuracy and control capabilities

- Task-oriented learned dynamics enable complex manipulation such as tool selection and multi-stage actions (example: robotic dumpling making)

- Learned models from real data can outperform hand-tuned physics simulators for contact-rich deformable tasks

- Imitation learning uses demonstrations to train policies but requires mitigation of distributional shift and cascading errors

- Implicit policy parameterizations and generative models (energy-based and diffusion policies) improve demonstration modeling for multimodal behaviors

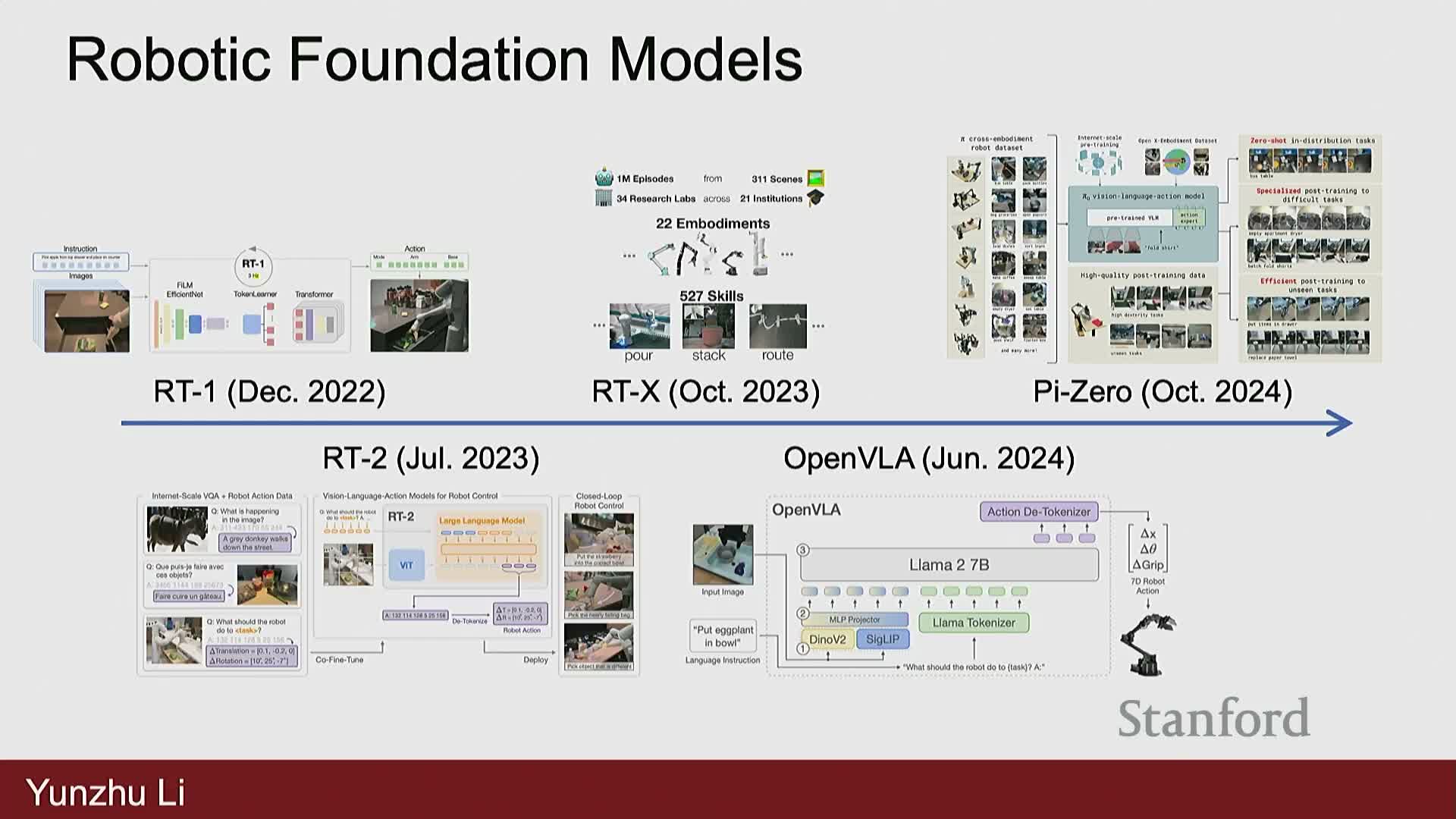

- Robotic foundation models aim to pretrain large action-conditioned policies on diverse datasets and then adapt via post-training

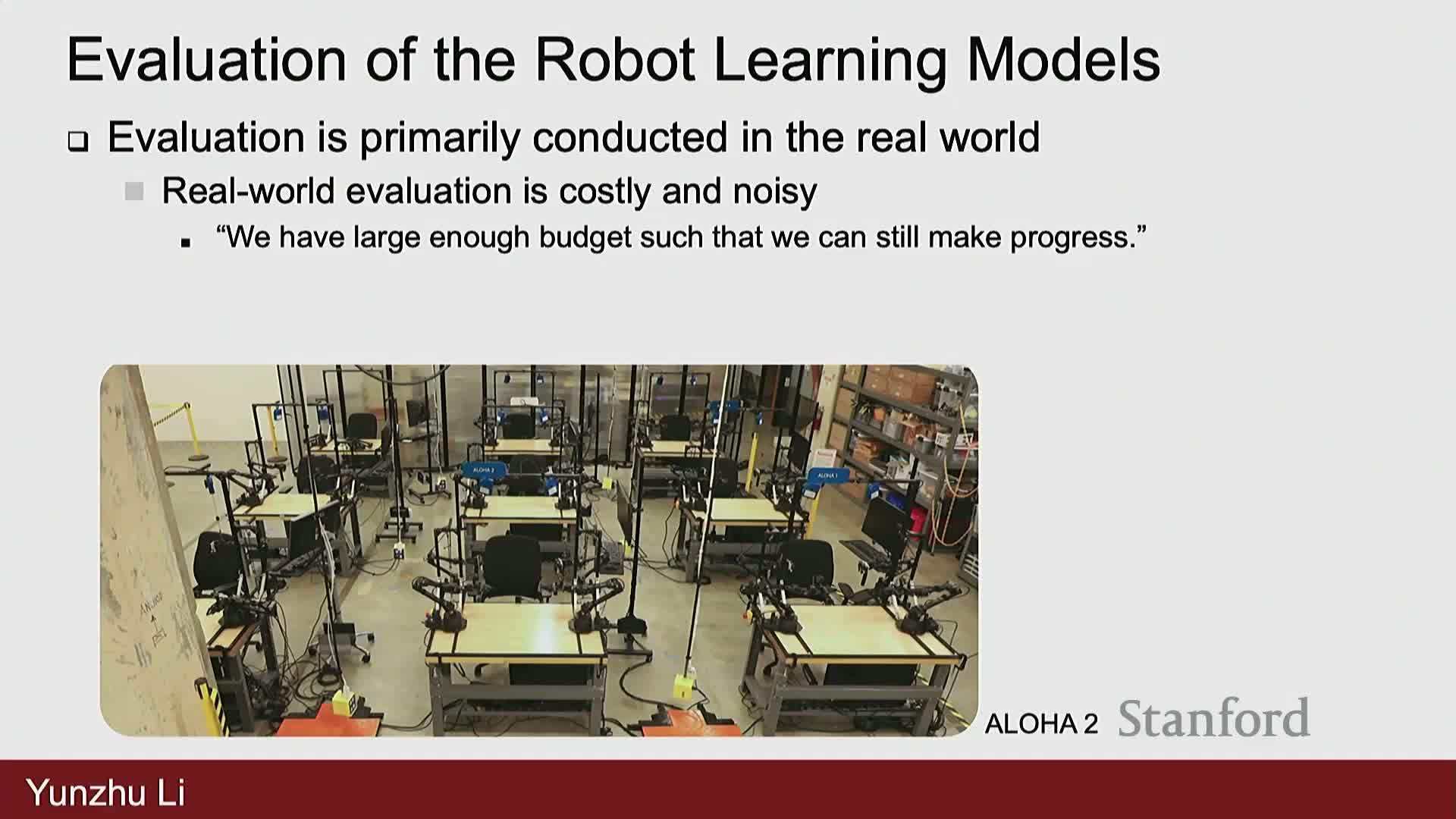

- Open challenges include evaluation, reproducible benchmarks, sim-to-real gaps, data assets, and efficient data collection

Introduction to robot learning as an interdisciplinary research area

Robot learning is an interdisciplinary field at the intersection of robotics, computer vision, and machine learning that targets expanding robots’ perception and physical interaction capabilities.

It frames research goals around enabling embodied agents to:

- perceive high-dimensional sensory inputs,

- act in the physical world, and

- improve behavior via learning.

Typical research activities include:

- developing perception systems for noisy, multimodal sensors,

- designing control policies that respect dynamics and constraints, and

- building decision-making frameworks for dynamic, uncertain environments.

The area connects academic investigations and industrial efforts aiming to build general-purpose robots capable of diverse manipulation and locomotion tasks.

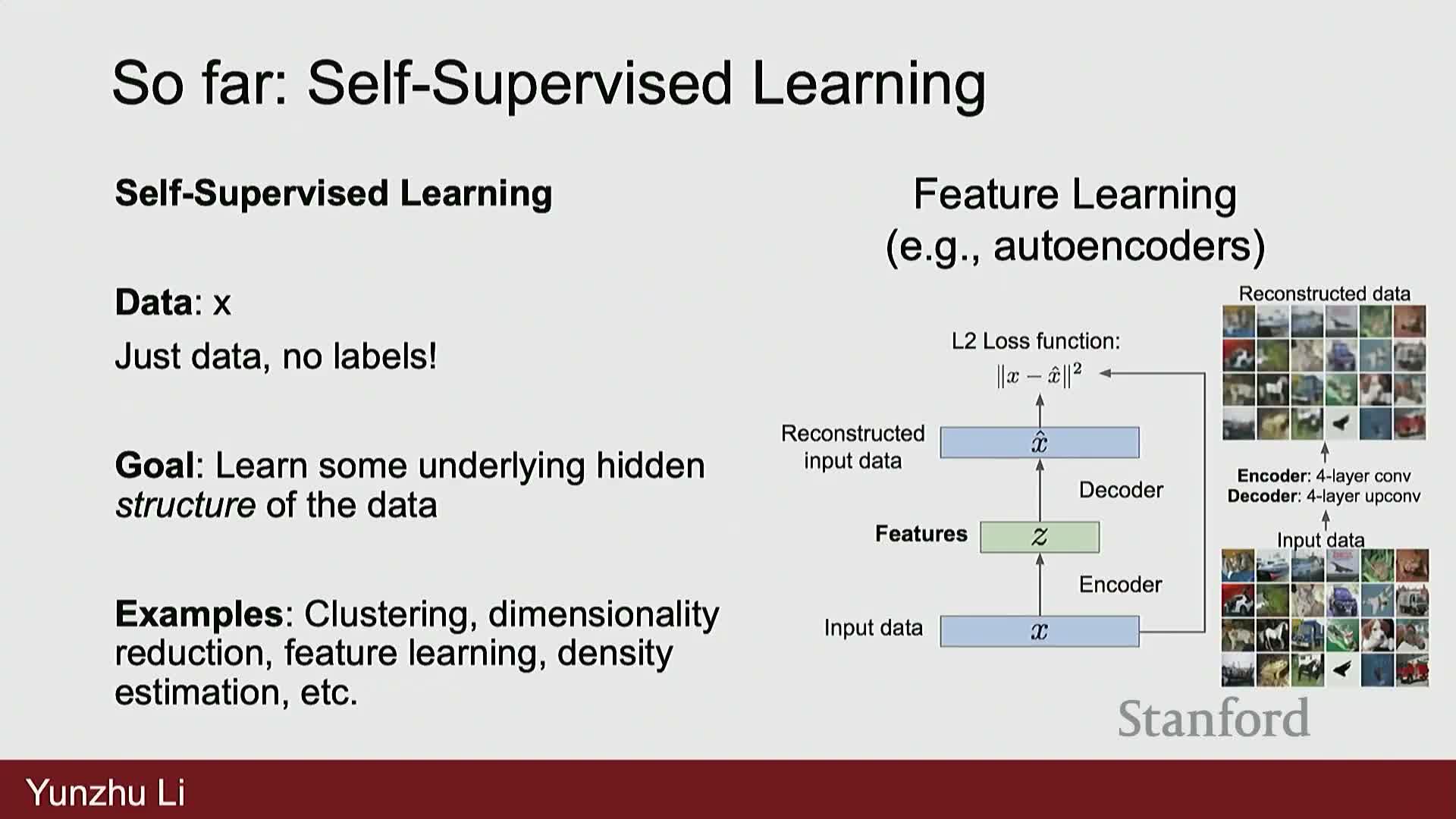

Contrast between supervised/self-supervised learning and robot learning

Supervised learning maps inputs X to labels Y using labeled datasets and loss minimization.

Self-supervised learning derives structure from unlabeled data via auxiliary objectives such as autoencoders or contrastive losses.

Robot learning differs fundamentally from these paradigms by incorporating sequential decision-making and physical interactions:

- actions executed by the agent change the environment and produce new observations and rewards,

- the learning target is typically a policy or control strategy that optimizes cumulative rewards under dynamics, not a static input→output mapping.

This distinction motivates distinct algorithmic choices and evaluation concerns in robotics versus traditional computer vision.

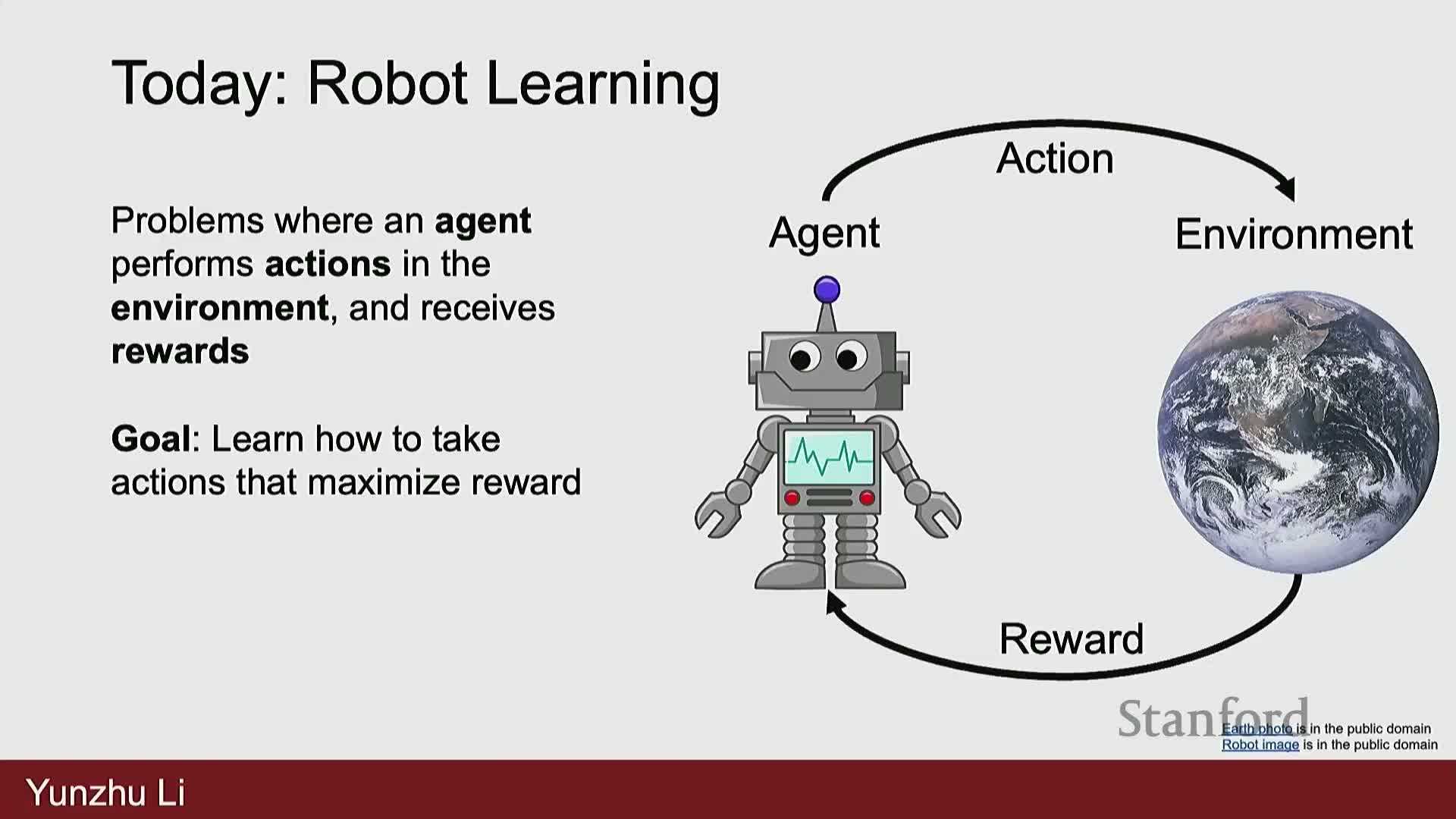

Robot learning emphasizes sequential actions that influence environment evolution and reward accumulation

Robot learning formalizes tasks where an agent chooses actions that produce state transitions and scalar feedback, and the objective is to produce action sequences that maximize cumulative reward or minimize cost.

Key problem components:

- Goal specifications (task objectives or instructions),

- State representations (what the agent observes and reasons about),

- Action spaces (discrete commands vs continuous motor controls), and

-

Reward functions (how success is quantified).

These elements jointly determine the optimization problem the agent must solve.

Real-world robotics introduces hard physical constraints, embodiment effects, and safety considerations that make the optimization substantially more difficult than static perception tasks.

The field has attracted significant academic and industrial investment aimed at building physically interactive, general-purpose robots.

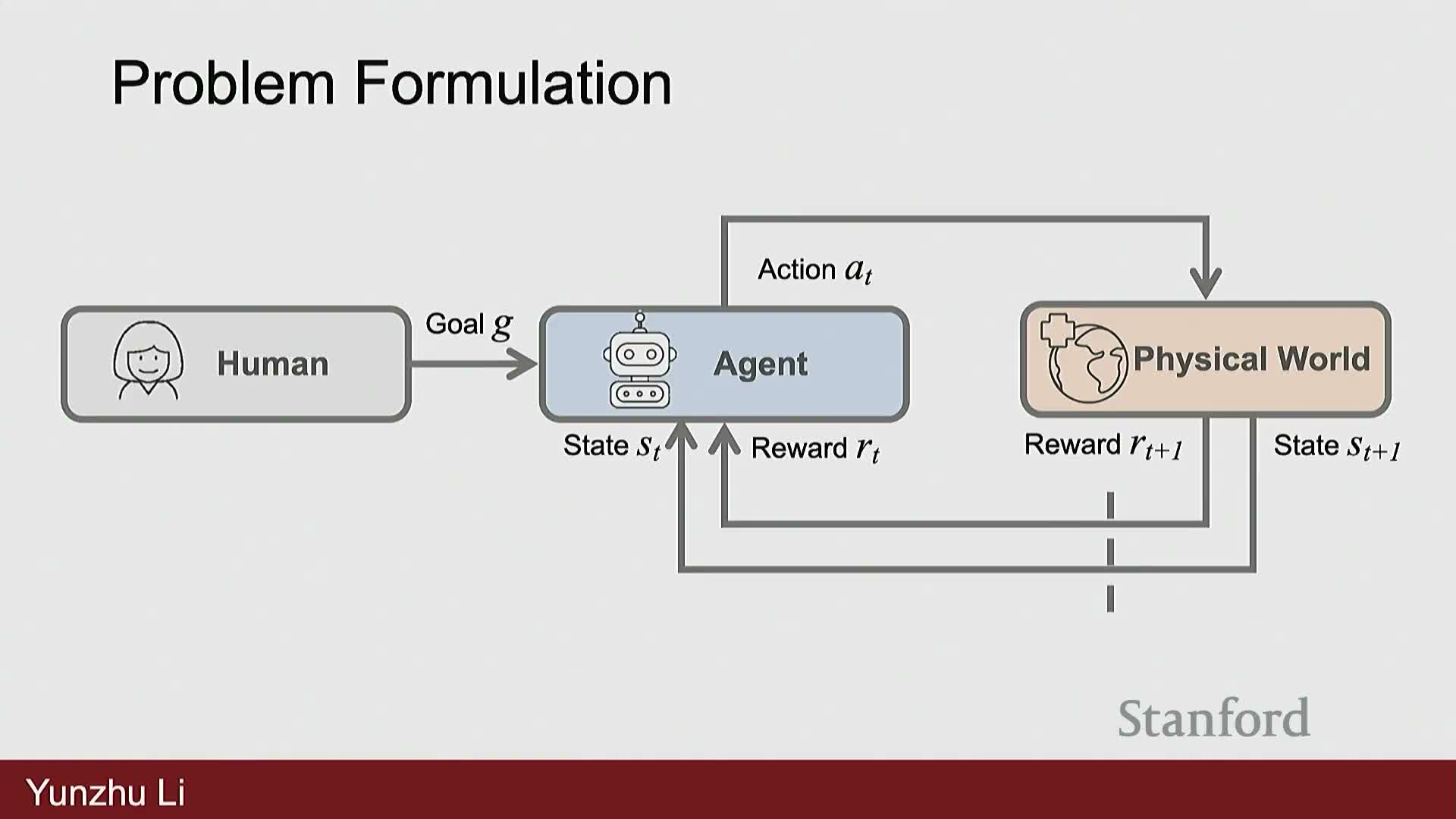

Problem formulation for embodied agents: goals, states, actions, and rewards

A canonical formalism represents an embodied agent interacting with an environment in a sequential loop:

- observe state S_t,

- execute action A_t,

- receive reward R_t, and

- transition to S_{t+1}.

The task objective may be:

- a human instruction,

- a scalar reward function, or

- a combination of both — and it must be specified to evaluate policy performance.

Representations and choices that shape learning:

- State representations: raw high-dimensional sensor data (e.g., RGB or RGB‑D frames) or lower-dimensional descriptors,

- Actions: discrete commands or continuous motor torques,

-

Reward shaping: design choices that affect learning behavior and safety.

This formalization distinguishes robotics from static perception by making control, dynamics, and constraints core elements of the problem statement.

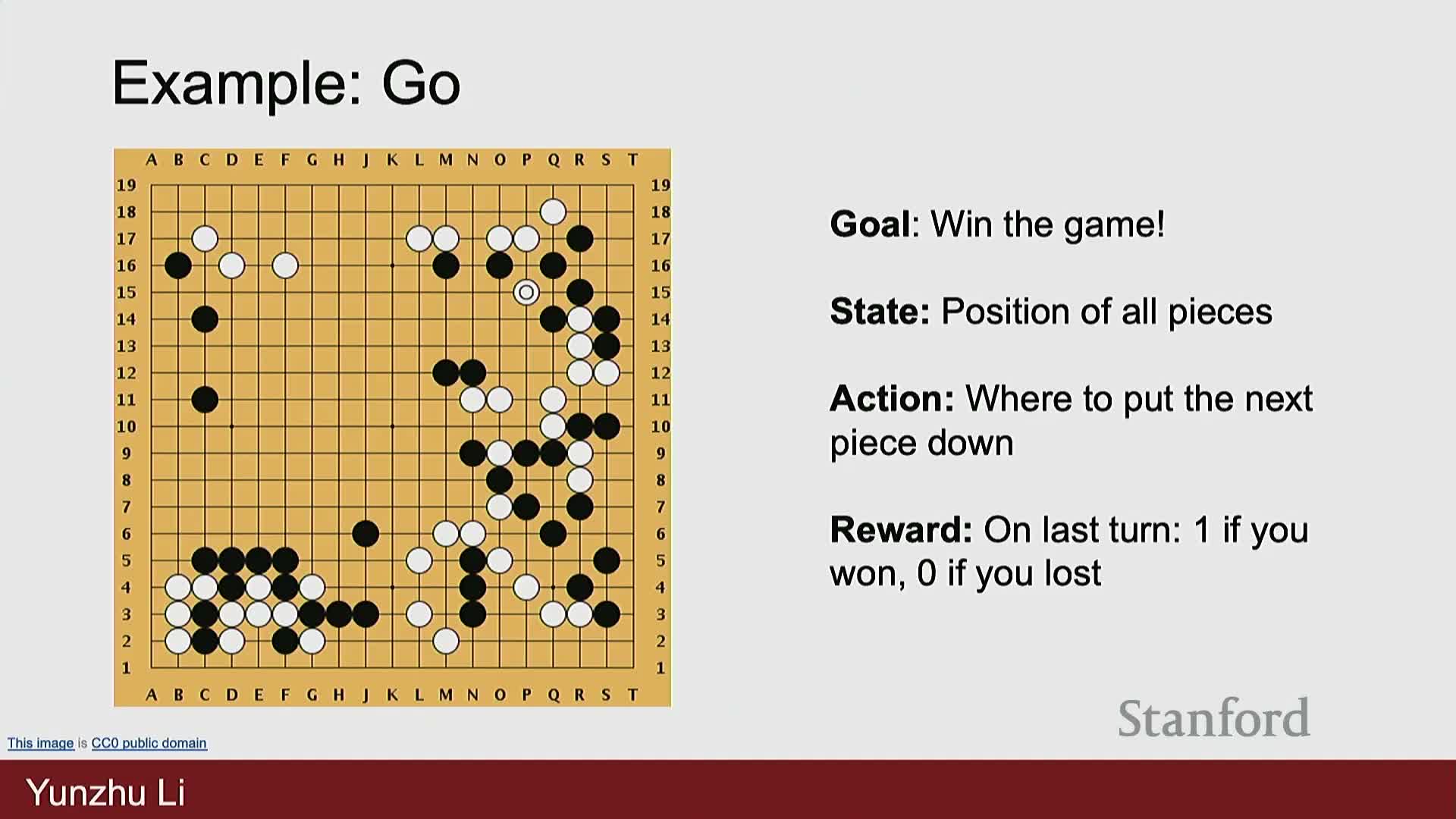

Instantiations of robot learning across domains (control, locomotion, games, language-conditioned agents, manipulation)

Robot learning maps naturally to diverse instantiations, each sharing sequential decision-making under dynamics but differing in state/action/reward choices:

- Classic control (e.g., cart-pole): low-dimensional physical state vectors and continuous forces.

- Locomotion: joint angles, velocities, and torques with rewards for forward progression and stability.

- Atari-style and board games: raw pixels or discrete board states cast into MDPs with discrete actions and episodic rewards.

- Language-conditioned generation / conversational agents: generated tokens as actions and human evaluations as rewards.

-

Manipulation (e.g., clothes folding): multimodal observations and binary or continuous success metrics.

Across these domains, the common structure is sequential decision-making under dynamics, while state/action representations and reward definitions vary and shape algorithm selection and evaluation.

Reward specification requires careful design and can be application specific

Reward design is task-dependent and can encode preferences, safety constraints, or multi-objective trade-offs.

Examples:

- autonomous driving rewards might prioritize speed, passenger comfort, or safety,

- cloth-folding rewards might emphasize compactness or smoothness as judged by human preferences.

Practical implications:

- Reward shaping and specification directly influence learned behaviors, generalization, and failure modes,

- ambiguous or underspecified rewards can yield undesired policies.

Common remedies:

- domain-specific reward engineering,

- human-in-the-loop evaluation and feedback, or

-

inverse methods (e.g., inverse reinforcement learning) that infer reward structure from demonstrations to better align agent behavior with user intent.

Robot perception is embodied, active, and situated and requires multisensory integration

Robot perception must extract structured, task-relevant information from high-dimensional, noisy, and incomplete sensory streams such as RGB/RGB‑D, tactile, and audio inputs.

Constraints and requirements:

- must operate robustly under occlusion, sensor noise, and dynamic environments,

- embodiment implies sensors are attached to the agent and actions immediately affect future observations,

- active perception: the agent chooses sensing actions (e.g., perturbation, viewpoint change) to disambiguate states,

-

situatedness: perception must be tightly coupled to current task goals and local regions rather than producing global, abstract descriptions.

Effective systems therefore:

- fuse complementary modalities,

- prioritize task-relevant information, and

- enable closed-loop perception–action coupling under uncertainty.

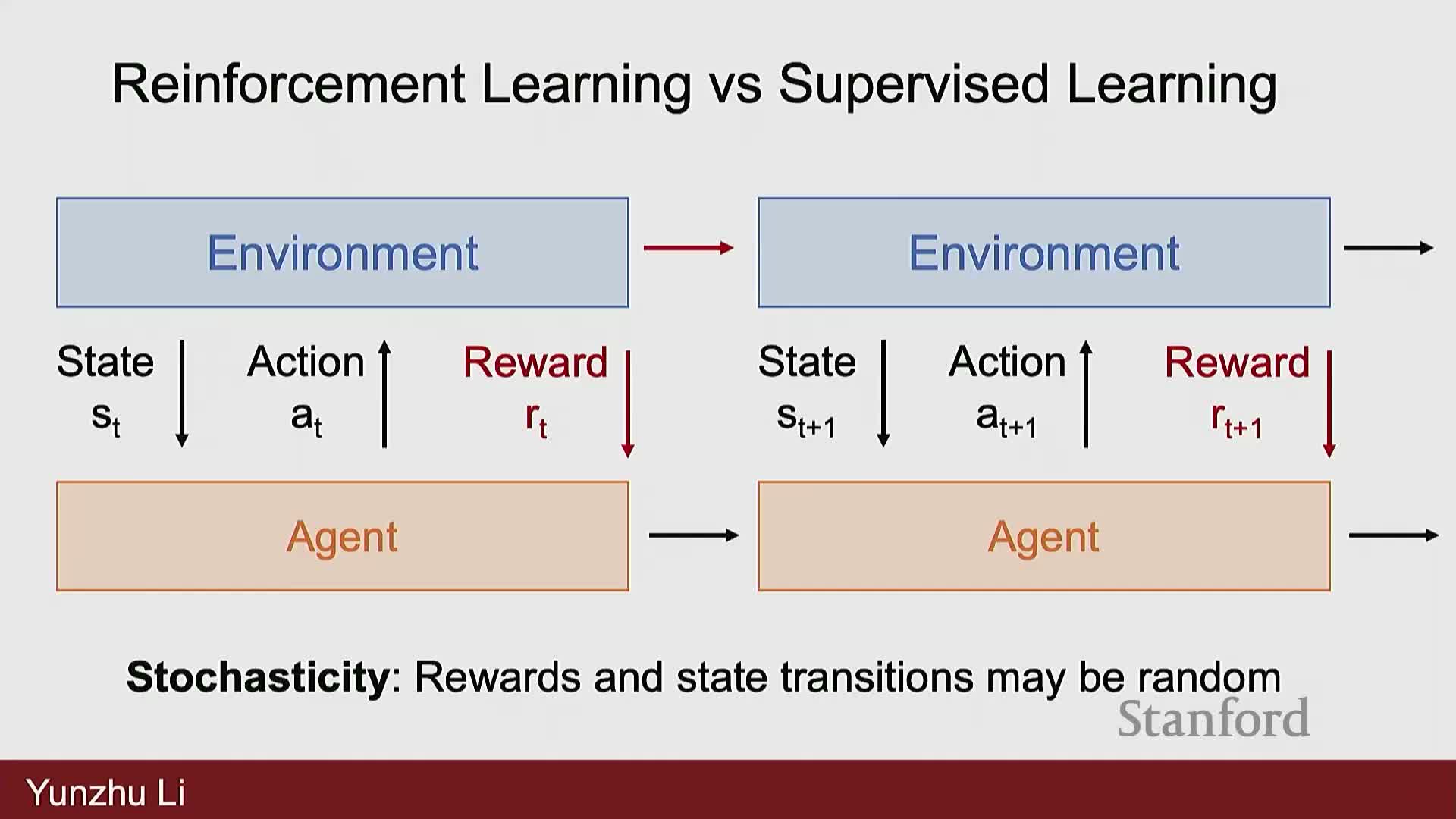

Reinforcement learning enables learning via trial-and-error interactions but differs fundamentally from supervised learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) uses environment interactions and reward feedback to adjust behavior through exploration and exploitation, typically by maximizing expected discounted cumulative reward.

How RL differs from supervised learning:

- environments can be stochastic and non‑stationary,

- rewards are often delayed, requiring long-horizon credit assignment,

- environments or reward functions may be non-differentiable, complicating gradient-based optimization,

- actions influence future data distributions (the agent’s behavior shapes the training data).

These differences motivate specialized RL techniques:

- value estimation (e.g., Q-functions),

- policy optimization algorithms (e.g., PPO, SAC), and

-

sample-efficiency strategies such as model-based methods, experience replay, and variance reduction.

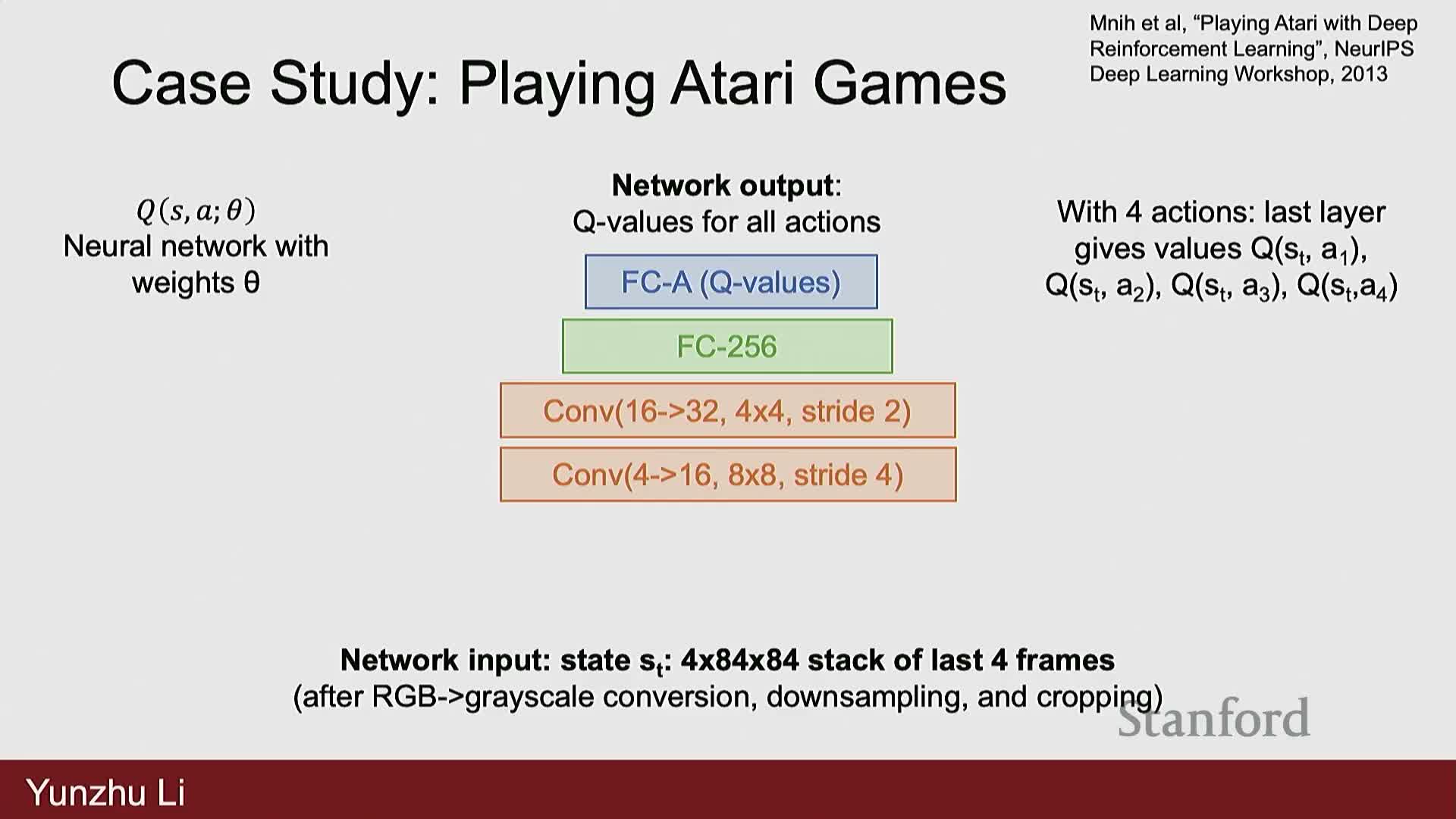

Value-based RL and large-scale policy learning demonstrate emergent strategies in simulated domains

Value-based algorithms learn action-value functions Q(s,a) that estimate discounted expected future returns and enable greedy or stochastic action selection.

Deep neural networks (e.g., convolutional networks for pixel inputs) serve as function approximators for Q and policy representations.

Empirical milestones:

- large-scale RL on domains like Atari shows agents can discover effective and sometimes novel strategies,

-

AlphaGo/AlphaZero families demonstrate self-play combined with value and policy networks can exceed human experts in complex games.

Takeaway: algorithmic design combined with compute scale and infrastructure can produce emergent, high-performing behaviors in well-defined simulated tasks.

Reinforcement learning succeeds in locomotion and faces challenges in manipulation in real world

Model-free RL coupled with domain randomization has yielded robust quadruped and humanoid locomotion controllers that transfer from sim to real and handle rough terrain.

Why locomotion succeeds more readily:

- dynamics can be randomized effectively in simulation, and

- control objectives are often well-structured and periodic.

Why manipulation remains challenging:

- larger sim-to-real gaps for contact-rich, deformable, or high-DoF interactions,

- high sample complexity and safety constraints limit online real-world exploration, and

- learned behaviors may be brittle or lack interpretability.

Mitigation strategies for manipulation:

- extensive engineering,

- richer sim-randomization, or

-

model-based approaches to improve sample efficiency and robustness.

Model-based learning and planning use learned forward models for predictive control and trajectory optimization

Model-based approaches learn a forward model f_theta(s_t, a_t) → s_{t+1} that predicts environment evolution under actions and then solve an inverse planning problem to reach target states by minimizing a trajectory loss in state space.

Typical pipeline (numbered):

- learn or fit a forward model f_theta(s_t, a_t) → s_{t+1},

- define a trajectory loss that measures deviation from desired states,

- optimize an action sequence via sampling-based trajectory optimization or gradient-based backpropagation through differentiable dynamics, and

- execute only the first action in a receding-horizon (MPC) manner to mitigate model errors.

Model-based pipelines often:

- exploit GPU parallelism for large-scale sampling and optimization, and

- enable interpretable, data-efficient control by leveraging explicit predictions of future states.

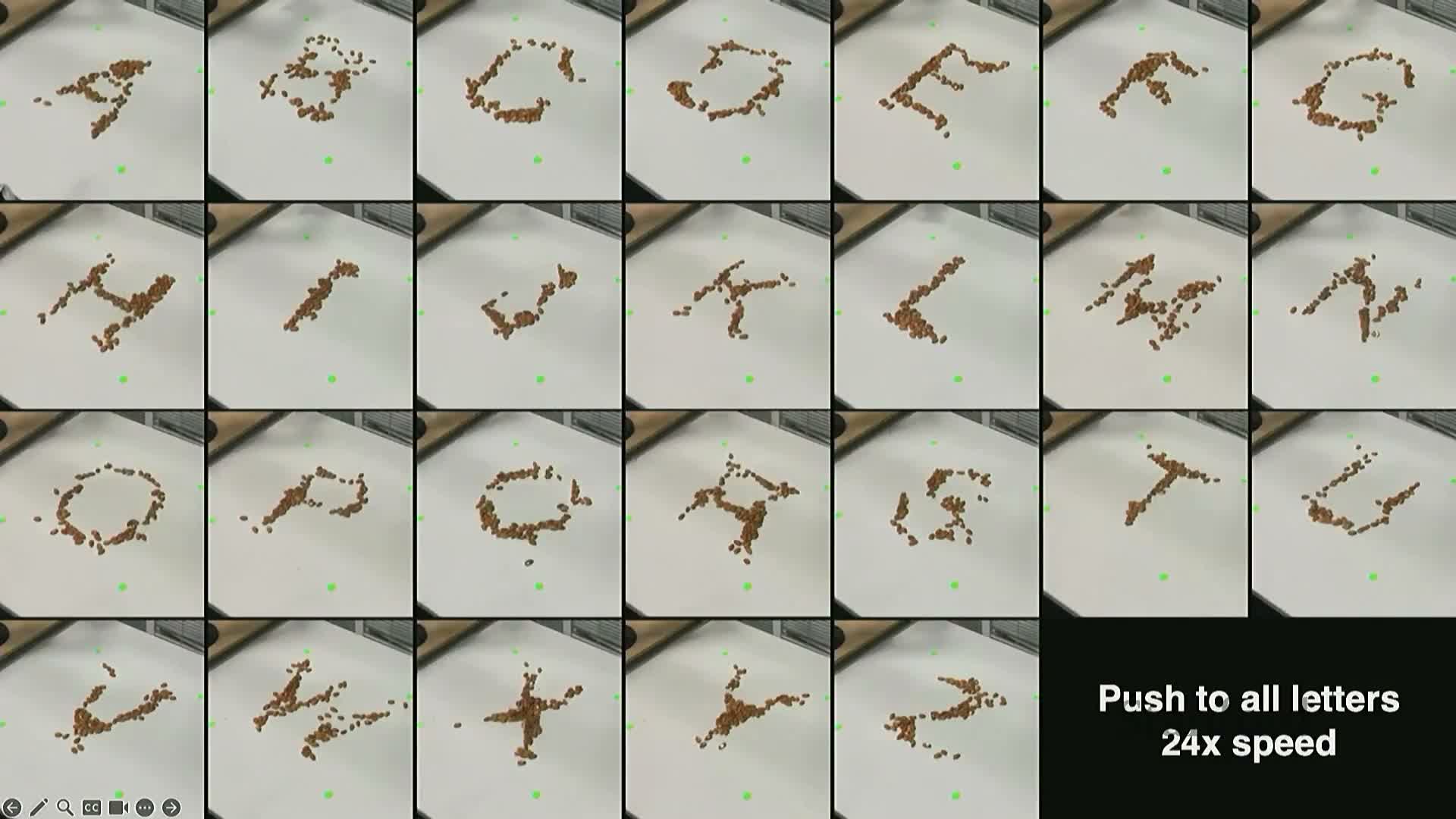

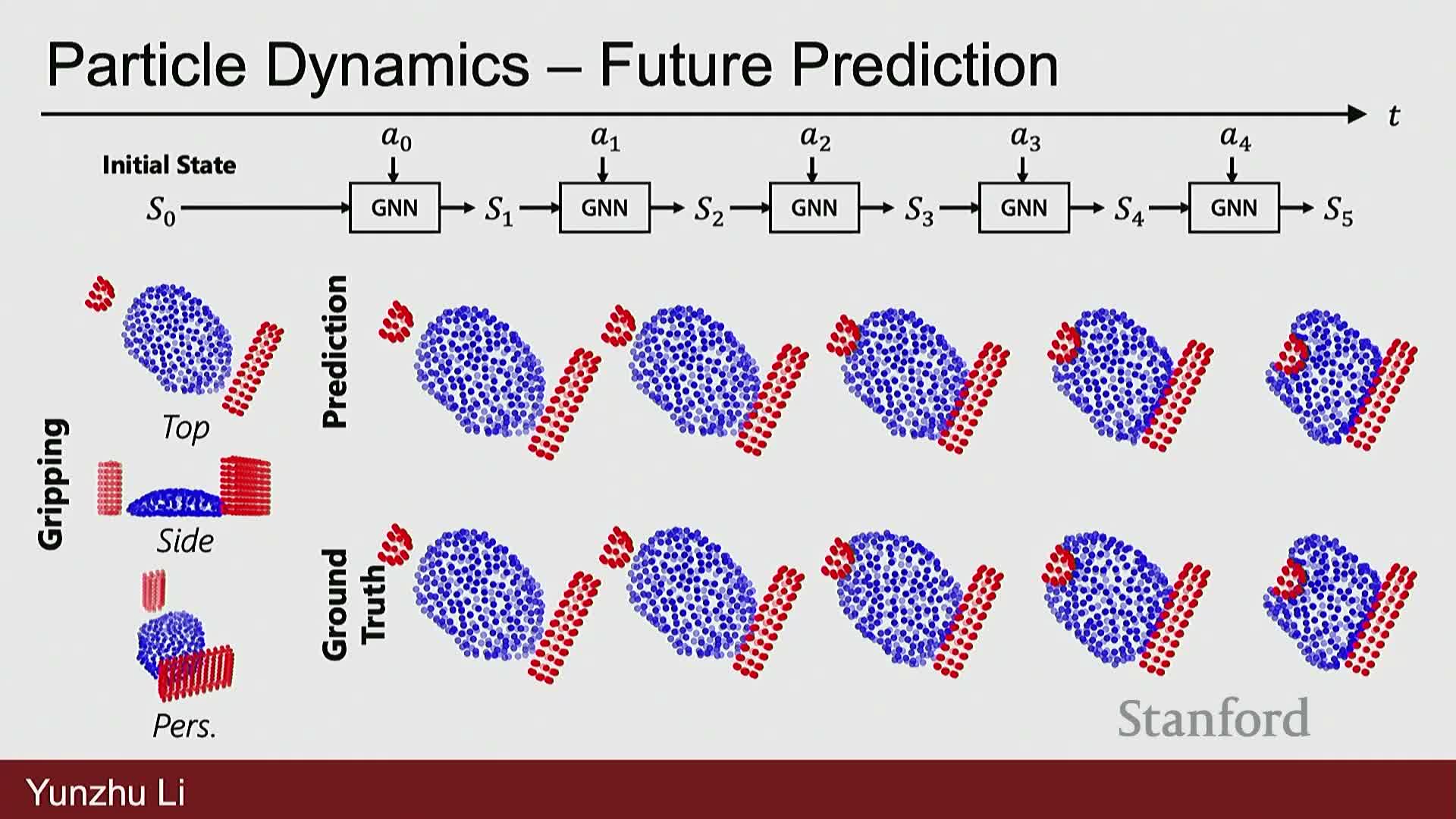

State representations for learned dynamics range from pixels to keypoints to particle-based models and dictate model accuracy and control capabilities

Choice of state representation critically affects the fidelity and tractability of learned dynamics:

- Pixel-level models predict image-space changes and enable visual servoing, but are high-dimensional and computationally expensive.

- Keypoint or low-dimensional descriptors provide compact, controllable features for object-centric planning.

-

Particle- or particle-fluid-based representations model high-DoF deformable or granular media, enabling fine-grained predictions for rearrangement tasks.

Learned neural dynamics over these representations make inverse planning feasible for complex materials; particle-based learned models have shown reliable performance on granular aggregation and deformable object manipulation by predicting multi-particle state evolution and supporting closed-loop correction.

Task-oriented learned dynamics enable complex manipulation such as tool selection and multi-stage actions (example: robotic dumpling making)

Learned forward dynamics over appropriate state representations support hierarchical decision-making:

- a high-level classifier or policy selects discrete options (e.g., tools or sub-tasks), and

- a low-level controller or planner optimizes continuous motions conditioned on that choice.

Empirical patterns:

- particle-based dynamics trained from real interaction data can predict deformable object evolution under different tools and support inverse planning to sequence tool choices and actions, enabling robust multi-stage manipulation (e.g., dough shaping, dumpling assembly).

- offline sampling-driven planning can be distilled into fast policies for runtime execution.

- closed-loop robustness is achieved by continuously reoptimizing or reclassifying the task stage based on current observations.

Learned models from real data can outperform hand-tuned physics simulators for contact-rich deformable tasks

Directly learned neural dynamics trained on real-world interaction data often produce more accurate open-loop and closed-loop predictions for complex deformable-object tasks than physics-based simulators that require extensive system identification (e.g., MPM implementations).

Empirical comparisons show:

- data-driven learned models can match observed shape evolution and support effective planning without accurate parametric physical models, and

- this mitigates certain aspects of sim-to-real mismatch.

Consequently, practitioners often prefer learning forward predictors from real interactions and using hybrid pipelines where planning and policy distillation leverage model predictions for robust control.

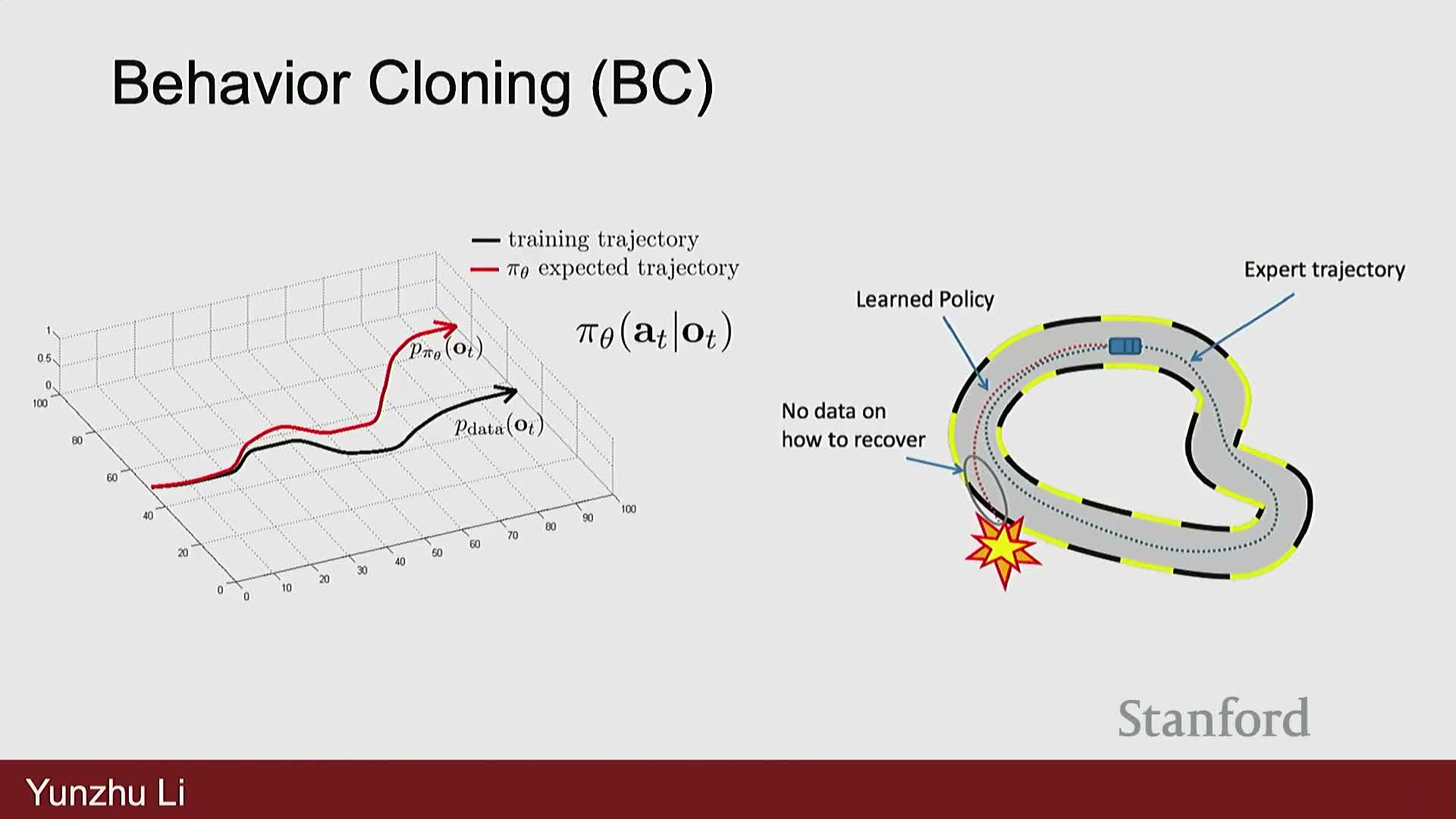

Imitation learning uses demonstrations to train policies but requires mitigation of distributional shift and cascading errors

Imitation learning (learning from demonstration) trains policies via supervised regression from observations to actions using expert data, with behavior cloning as a canonical algorithm that optimizes an action prediction loss.

A central challenge is covariate shift and cascading errors: small deviations from the expert trajectory lead to out-of-distribution states that amplify mistakes over time and degrade long-horizon performance.

Practical remedies:

- augment demonstrations with corrective data collection,

- use interactive refinement (e.g., DAgger-style collection),

- apply inverse reinforcement learning to infer implicit rewards, or

- combine imitation with reinforcement fine-tuning to recover from errors and improve robustness.

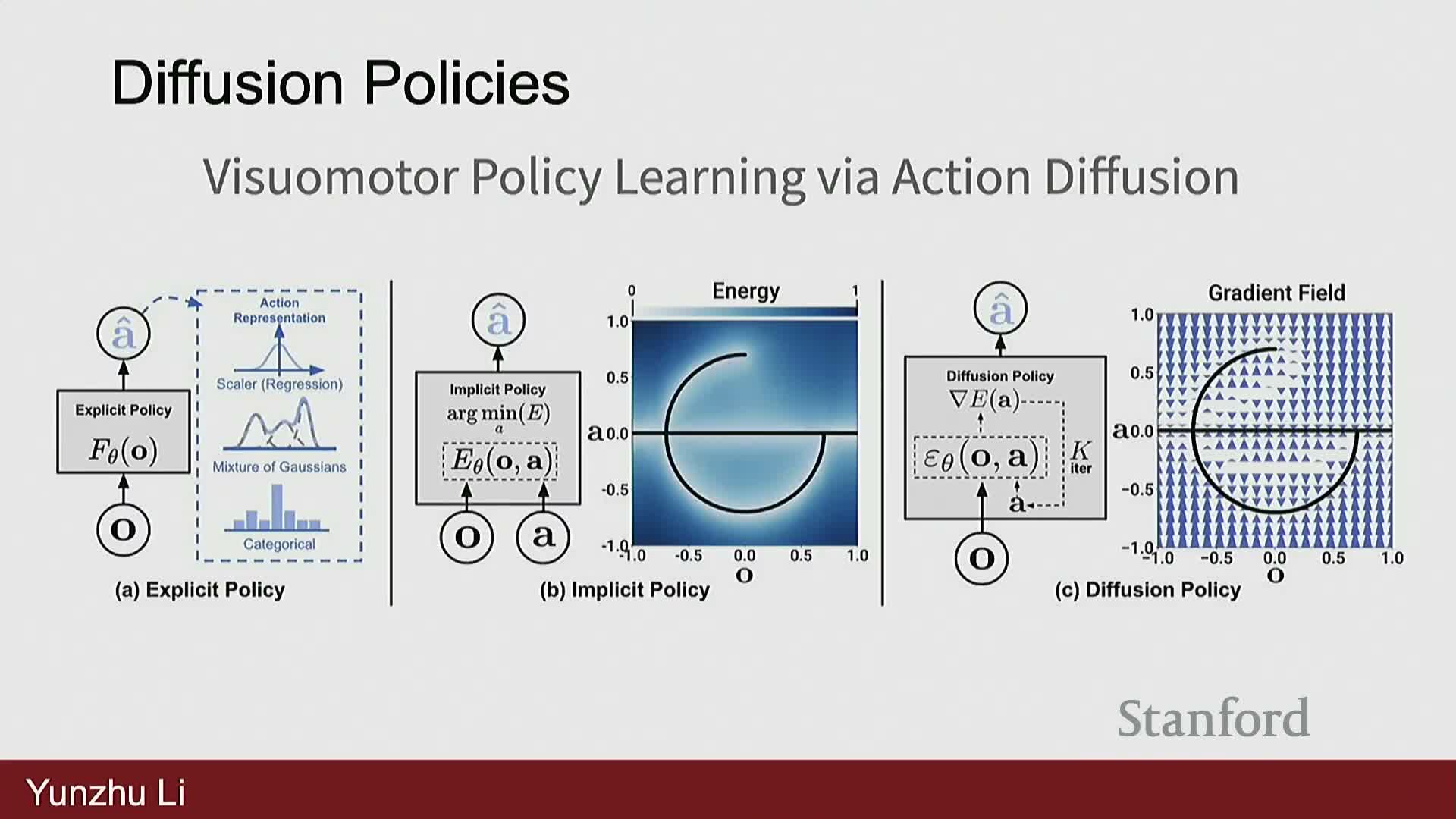

Implicit policy parameterizations and generative models (energy-based and diffusion policies) improve demonstration modeling for multimodal behaviors

Implicit policy models inspired by energy-based models and diffusion generative models represent a scoring function or denoising process over action trajectories conditioned on observations.

Key benefits:

- enable multimodal behavior modeling and more expressive inference than direct regression,

-

diffusion policy methods model distributions over action sequences and sample via iterative denoising, capturing diverse valid behaviors in ambiguous tasks, and producing smoother, higher-quality motion trajectories.

These generative policy classes have enabled recent real-world manipulation improvements by better matching the multimodal distribution of expert behaviors and supporting stable sampling-based inference.

Robotic foundation models aim to pretrain large action-conditioned policies on diverse datasets and then adapt via post-training

Robotic foundation models generalize the foundation model pattern to embodied action by pretraining large observation→action policies on aggregated multi-robot, multi-task datasets, often leveraging pretrained vision-language backbones to inherit semantic understanding.

Typical workflow:

- pretraining provides broad semantic and perceptual priors,

- post-training or task-specific fine-tuning on curated robot interaction data improves action-level performance and reliability for target tasks.

Evaluation regimes include:

- zero-shot use of the base model,

- in-distribution post-training, and

- out-of-distribution fine-tuning.

Successful systems combine scale of data, representation priors, and specialized adaptation to achieve practical capabilities.

Open challenges include evaluation, reproducible benchmarks, sim-to-real gaps, data assets, and efficient data collection

Quantitative evaluation of robotic systems remains a major bottleneck because real-world testing is expensive, noisy, and sensitive to initial conditions, hardware tolerances, and environmental factors.

Consequences and challenges:

- weak correlations between training losses and real-world task success,

- simulated evaluation helps but suffers from asset realism limits, procedural generation gaps, and uncertain sim-to-real transferability—especially for contact-rich, deformable, or friction-sensitive tasks, and

- difficulty building large, diverse datasets of action-conditioned interactions and achieving efficient data-collection speeds comparable to humans.

Additional needs:

- robust, safety-aware learning for on-robot trials, and

- principled metrics and benchmarks to measure generalization and community progress.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: