Stanford CS231N Deep Learning for Computer Vision | Spring 2025 | Lecture 18- Human-Centered AI

- This lecture frames vision research through a human-centered perspective and outlines three directions: seeing what humans see, seeing what humans do not see, and seeing what humans want to see.

- Vision evolved as a primary sensory system and human visual processing achieves rapid, object-focused recognition.

- Early computer vision progressed from part-based models to statistical machine learning and was fundamentally limited by available data and model capacity.

- Large-scale datasets and convolutional neural networks catalyzed the deep learning revolution and dramatically advanced object recognition.

- Visual intelligence requires reasoning about object relationships and semantics beyond categorical labels.

- Engineering AI to exceed human perception targets fine-grained recognition and population-scale visual analysis.

- Human attention and perception have systematic limits that can cause critical errors in high-stakes domains.

- Human visual biases and privacy concerns necessitate fairness-aware and privacy-preserving sensing methods.

- AI can both amplify human capabilities and amplify human biases, so human-centered values must guide AI development and deployment.

- AI can augment labor shortages by providing ambient intelligence in healthcare to monitor and assist patients.

- Smart sensing supports ICU monitoring and aging-in-place use cases but physical assistance requires robotics to close perception-to-action gaps.

- Integrating large language models with visual-language models enables open-instruction robotic manipulation in diverse, unstructured environments.

- Developing ecological robotic benchmarks requires human-centered task selection and realistic simulation assets for generalization.

- Current robotic algorithms perform poorly on zero-privilege, in-the-wild behavior tasks, revealing a large gap between lab progress and real-world needs.

- Closing perception-action loops includes non-invasive brain interfaces and emphasizes AI as augmentation rather than replacement.

This lecture frames vision research through a human-centered perspective and outlines three directions: seeing what humans see, seeing what humans do not see, and seeing what humans want to see.

The lecture introduces a human-centered framing for computer vision research that foregrounds historical context, cognitive inspiration, and the societal impacts of vision systems.

It organizes the material into three high-level directions:

-

Replicate human seeing — build AI that mirrors human perceptual mechanisms and constraints.

-

Exceed human perception — leverage scale and statistics to reach capabilities beyond individual humans.

-

Connect perception to human-desired action — close the loop from sensing to useful, safe interventions.

This framing argues that technical progress should be evaluated not only by algorithmic metrics but also by alignment with human values, privacy, bias, and practical utility.

The introduction positions the rest of the talk as a survey of technical progress, open problems, and human-centered applications.

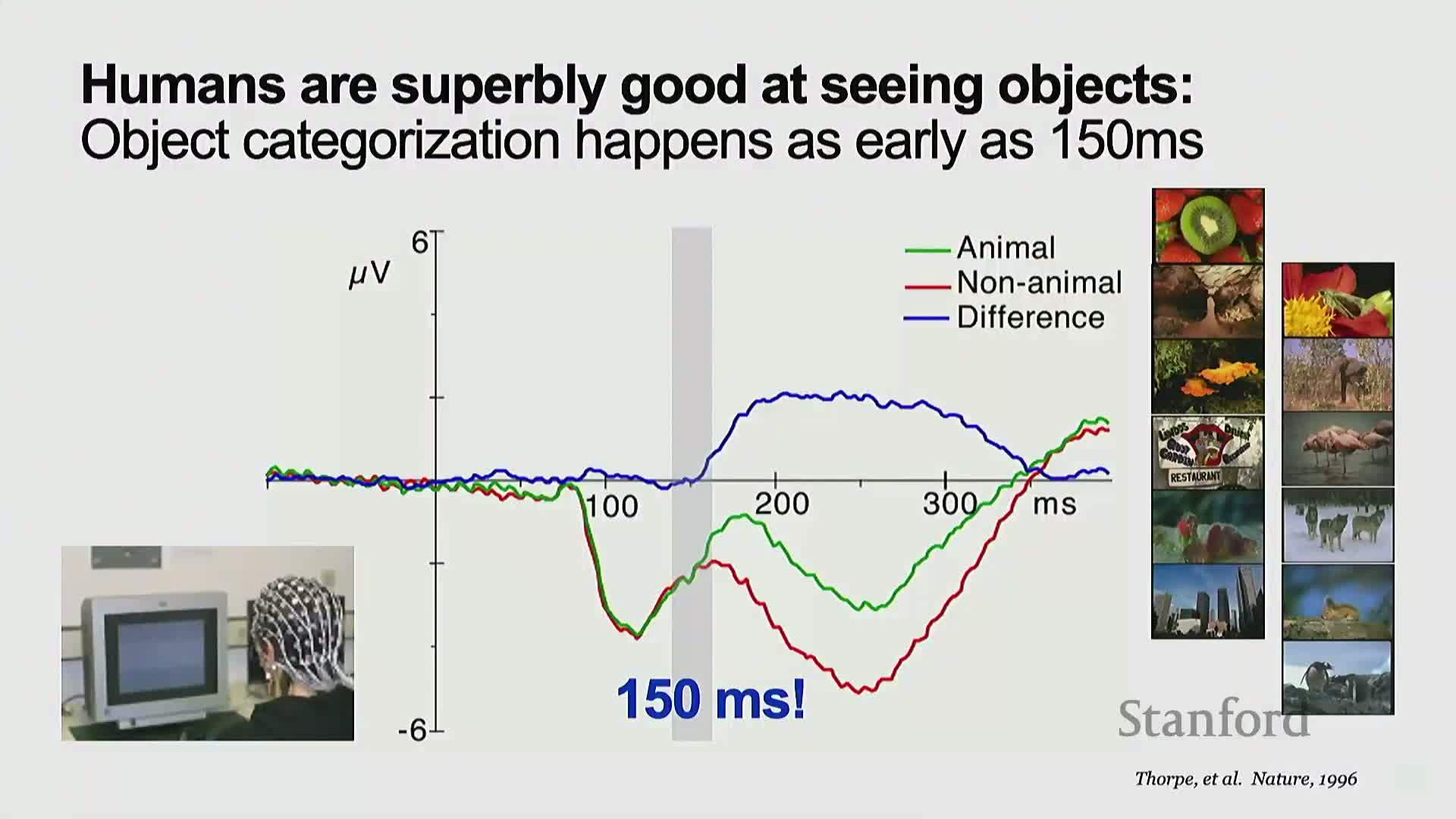

Vision evolved as a primary sensory system and human visual processing achieves rapid, object-focused recognition.

Vision emerged early in animal evolution and catalyzed rapid ecological and phenotypic diversification, which explains why visual perception is a core intelligence modality across species.

Key human characteristics that motivate computational vision design:

-

Fast, object-focused recognition — electrophysiological signals show categorical differentiation (e.g., animal vs. non-animal) within ~150 ms of stimulus onset.

-

Neuroanatomical specialization — dedicated regions for faces, places, and bodies indicate object recognition is deeply embedded in brain organization.

- These biological features provide inspiration and constraints for computational models and motivate object-centric formulations and benchmark tasks in computer vision.

Early computer vision progressed from part-based models to statistical machine learning and was fundamentally limited by available data and model capacity.

Early object recognition approaches emphasized hand-designed part/shape compositional models that represented objects as arrangements of primitives.

- Strengths: conceptually appealing, interpretable compositional structure.

- Weaknesses: brittle to real-world variability such as lighting, occlusion, and articulation.

The next wave used statistical machine learning and framed recognition as parameter estimation, using models like:

-

Markov random fields (MRFs)

-

Bag-of-features representations

-

Support vector machines (SVMs)

These methods exposed the dependence of performance on curated benchmarks, dataset scale, and diversity.

Psychophysical estimates that humans know tens of thousands of visual categories highlighted the gulf between human experience and early vision taxonomies, motivating large-scale dataset collection.

Large-scale datasets and convolutional neural networks catalyzed the deep learning revolution and dramatically advanced object recognition.

The confluence of large, diverse datasets, increased compute, and modern neural network architectures produced a qualitative leap in object recognition.

-

ImageNet-scale datasets supplied orders-of-magnitude more labeled examples and broader taxonomic coverage.

-

Deep convolutional networks learned robust, hierarchical feature extractors from this scale of data.

- The 2012 ImageNet moment demonstrated how data + compute + convolutional architectures unlocked performance unattainable by hand-designed features or smaller models.

Practical outcomes and remaining challenges:

- Industrial applications matured for many standard categories.

- Persistent problems include the long tail of rare classes, challenging conditions, and domain shifts that still require further research.

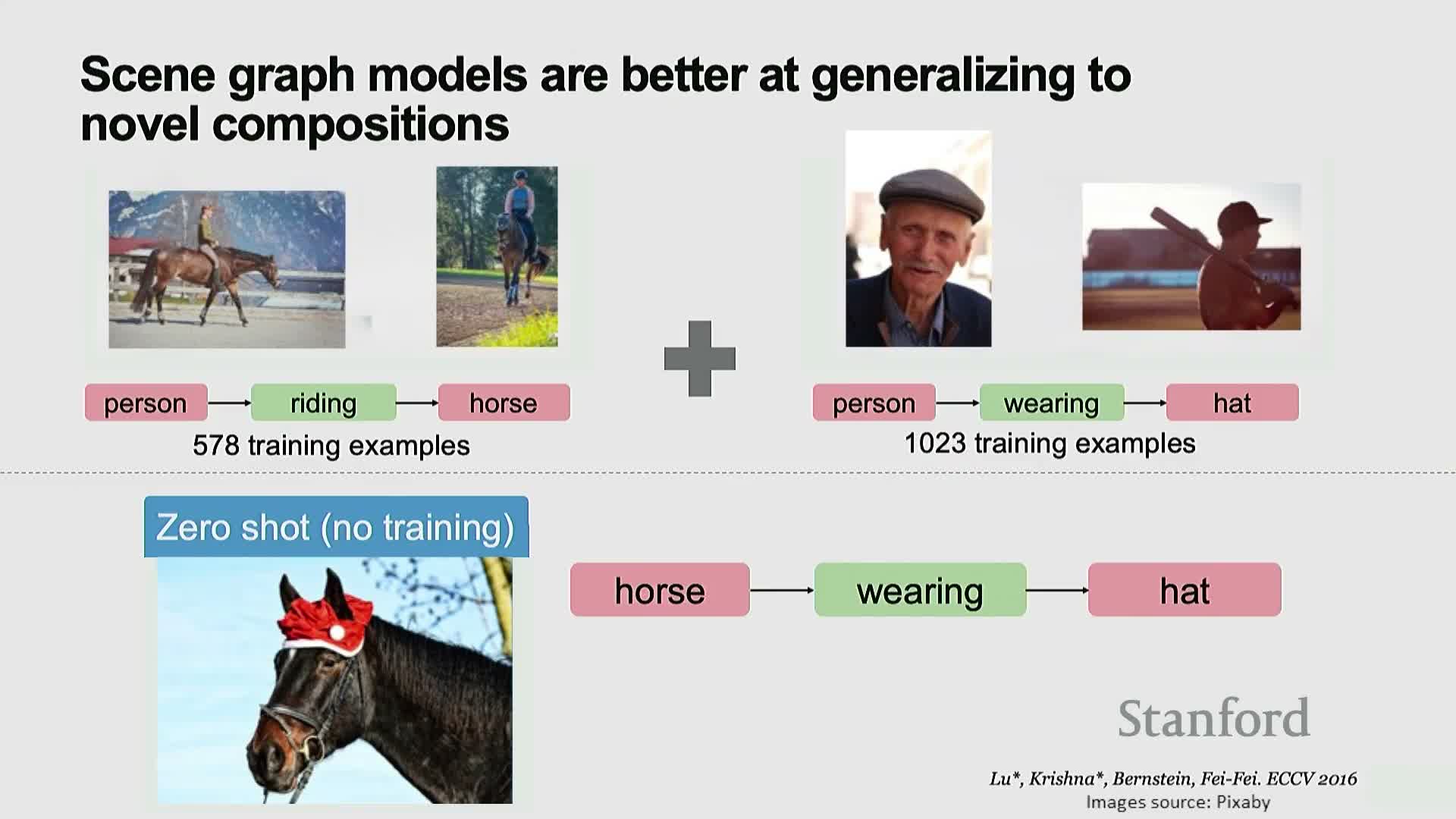

Visual intelligence requires reasoning about object relationships and semantics beyond categorical labels.

Understanding full scenes requires more than per-object labels; it requires encoding relationships, attributes, and higher-order semantics.

-

Scene graphs formalize scene structure by representing objects as nodes and relationships (spatial relations, actions, attributes) as edges, enabling compositional representations and relational queries.

- Datasets and tasks such as Visual Genome, dense captioning, and image captioning combine object detection with language models to produce natural-language descriptions and narrative scene understanding.

-

Dynamic, multi-actor activity understanding demands temporal reasoning about who does what, when, and how actors interact — a still-active and largely unsolved frontier.

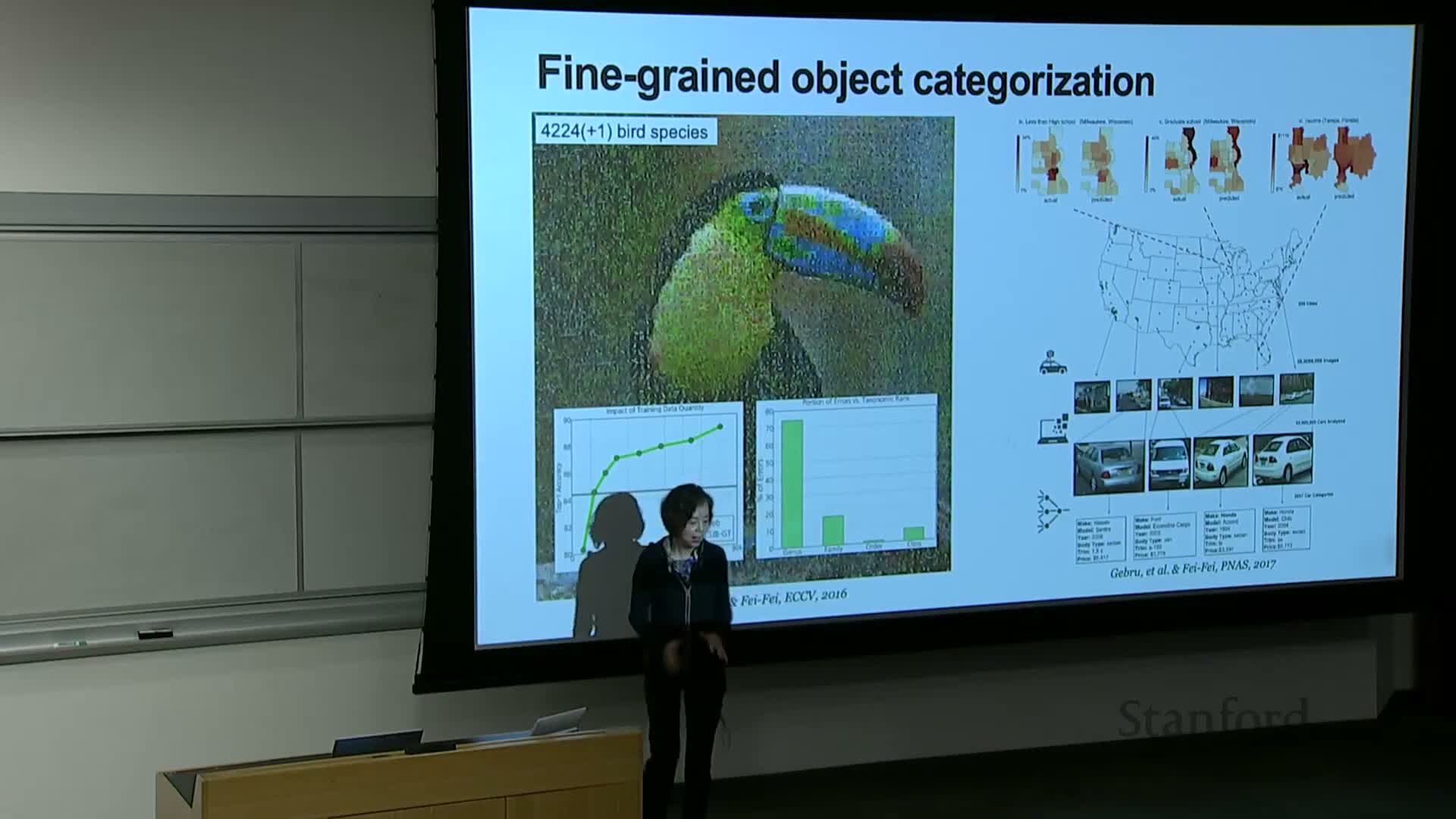

Engineering AI to exceed human perception targets fine-grained recognition and population-scale visual analysis.

Superhuman visual capabilities exploit scale and fine-grained discrimination to exceed what individual humans can do.

- Examples: distinguishing thousands of bird species or fine-grained car make/model/year variants.

- Requirements: specialized datasets, high intra-class discrimination, and often hierarchical taxonomies to capture subtle differences.

- At population scale, street-level imagery combined with fine-grained detectors enables statistical analyses of socioeconomic patterns, voting behaviors, or environmental signals that single observers cannot efficiently extract.

These capabilities act as a sociological lens but also raise important ethical and appropriate-use questions.

Human attention and perception have systematic limits that can cause critical errors in high-stakes domains.

Behavioral findings like Stroop interference and change blindness show that human visual attention is limited and can miss salient events even in clear displays.

- In high-stakes domains (e.g., surgery, medical care), these attentional limits contribute to diagnostic and procedural errors and make medical error a significant cause of harm.

- Manual mitigations (checklists, human auditors) are brittle, costly, and subject to fatigue.

- Continuous automated monitoring with vision systems can provide consistent counts and alerts to reduce risk, but deployments require careful validation, privacy preservation, and integration with clinical workflows.

Human visual biases and privacy concerns necessitate fairness-aware and privacy-preserving sensing methods.

Human perception is shaped by evolutionary and cultural priors that induce systematic biases and optical illusions; training data can further encode social bias, producing unfair outcomes.

- Historical issues in face recognition show disparate performance across demographic groups, underlining the need for detection, auditing, and mitigation strategies to improve fairness.

-

Privacy motivates technical approaches such as:

-

Blurring and masking

-

Dimensionality reduction

-

Federated learning

-

Encryption

-

Hybrid hardware–software solutions that filter raw imagery at capture time

-

Blurring and masking

- Carefully designed sensing pipelines can preserve task-specific information (e.g., for activity recognition) while obfuscating identity and sensitive attributes to respect individual privacy.

AI can both amplify human capabilities and amplify human biases, so human-centered values must guide AI development and deployment.

Automated vision systems can extend human perception where attention, scale, or granularity are limiting — but they can also magnify biases or introduce new harms if values and safeguards are absent.

A human-centered development process should include:

- Forecasting societal impacts and abuse modes.

- Evaluating fairness and privacy trade-offs.

- Engaging interdisciplinary perspectives from cognitive science, neuroscience, ethics, and policy.

Operationalizing human values requires:

- Measurement and transparent reporting of limitations.

- Deployment choices that prioritize augmentation and safety over blanket automation.

- Continuous collaboration between technical teams and domain stakeholders to align system objectives with human welfare.

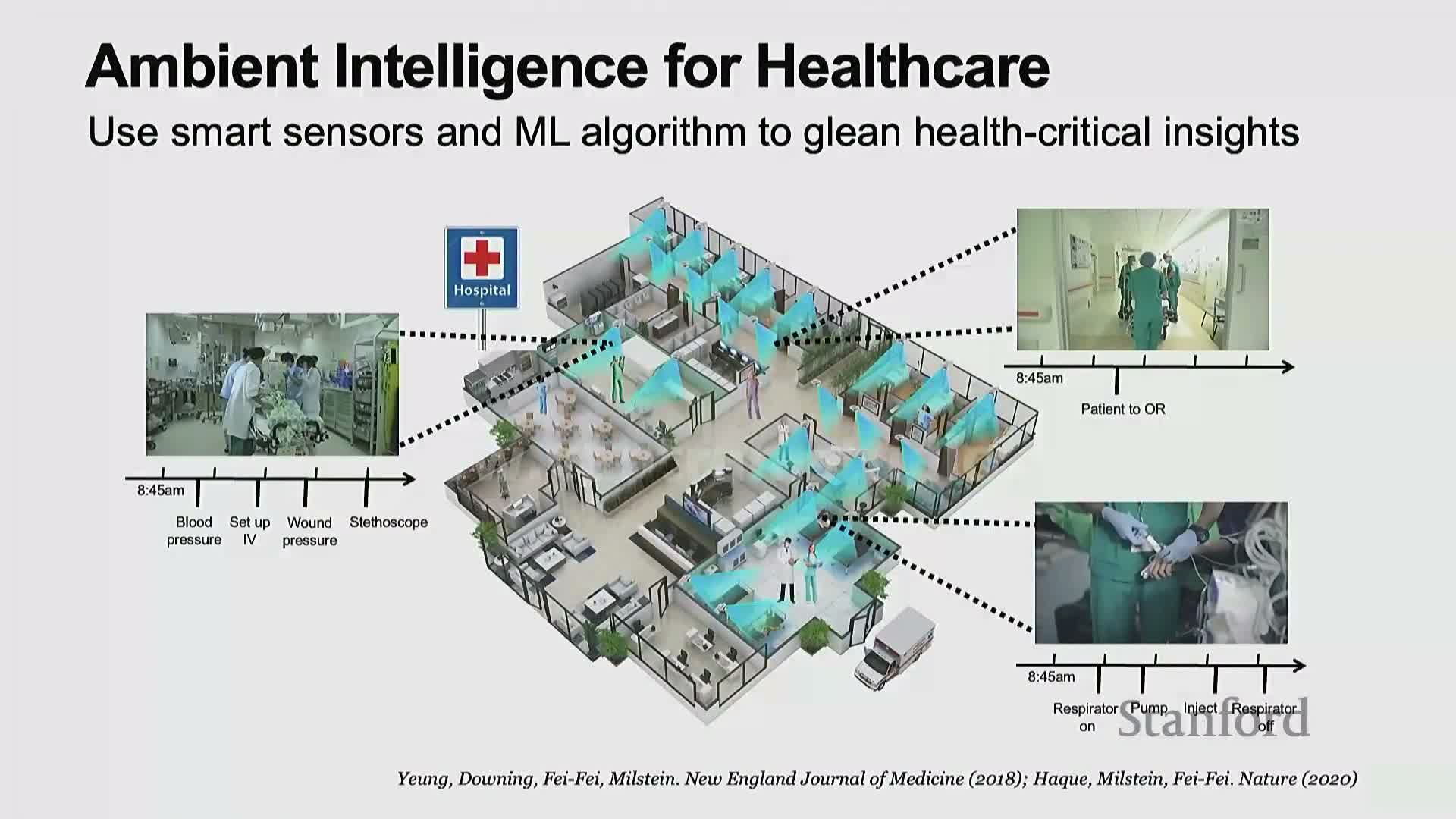

AI can augment labor shortages by providing ambient intelligence in healthcare to monitor and assist patients.

Rather than viewing AI purely as labor replacement, many applications benefit when AI augments human capability, especially in domains with chronic labor shortages (e.g., elder care, healthcare).

-

Ambient intelligence combines distributed sensors with machine learning to provide continuous, privacy-aware monitoring that detects critical events and supports timely interventions.

- Example: automatic hand-hygiene monitoring using privacy-preserving depth sensors and computer vision models can classify actions more reliably than sparse human auditors.

- Such systems can reduce hospital-acquired infections and provide scalable surveillance for tasks impractical for continuous human monitoring.

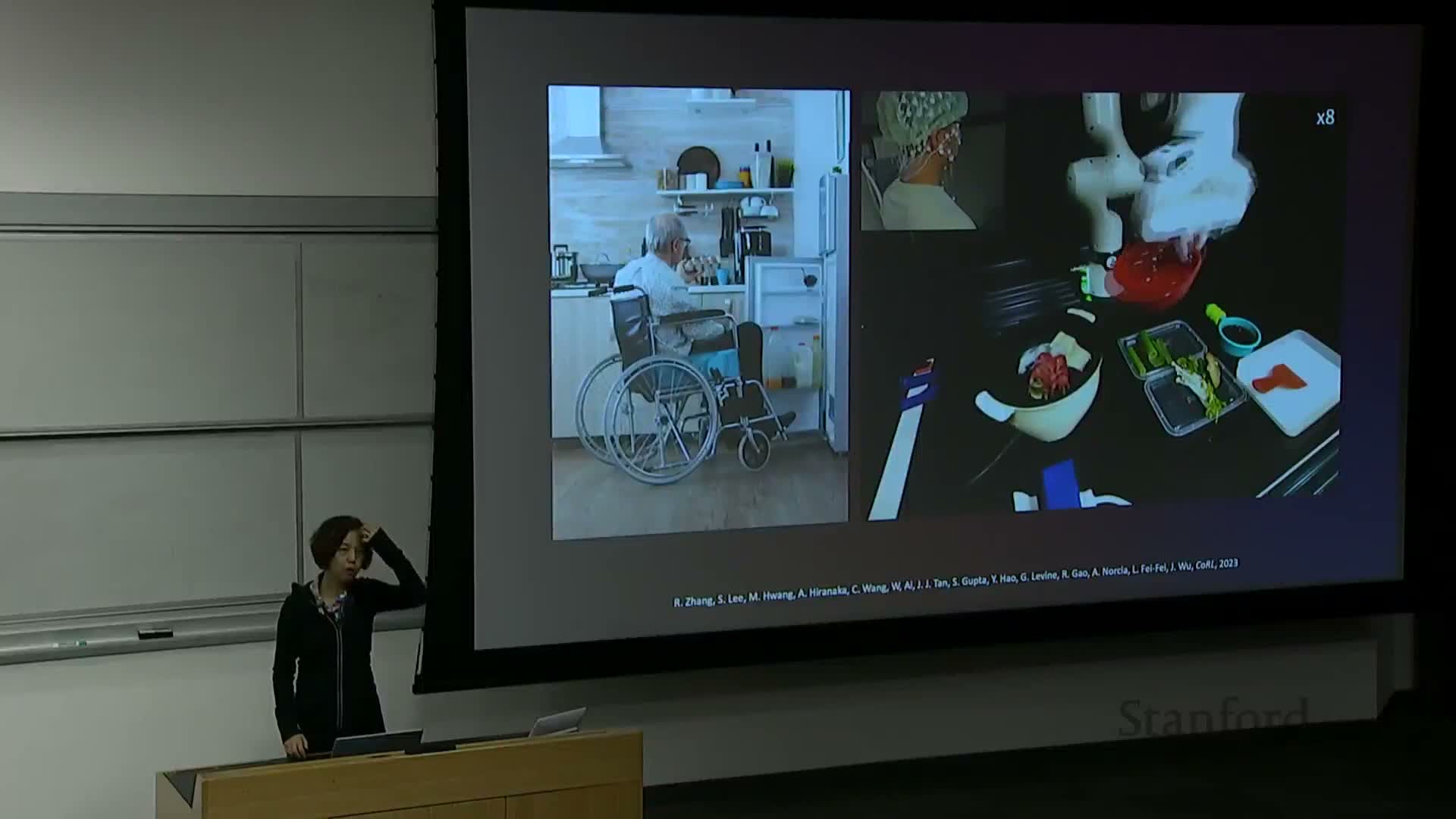

Smart sensing supports ICU monitoring and aging-in-place use cases but physical assistance requires robotics to close perception-to-action gaps.

Smart sensors and vision systems support clinical monitoring and aging-in-place applications but cannot by themselves perform physical assistance — closing perception to action requires robotics.

- Clinical applications:

- Monitor ICU patient mobilization and detect specific patient movements.

- Predict risks to improve outcomes and resource allocation.

- Monitor ICU patient mobilization and detect specific patient movements.

- Aging-in-place sensing:

-

Thermal sensing, mobility tracking, sleep and dietary monitoring for early infection detection and health maintenance at home.

-

Thermal sensing, mobility tracking, sleep and dietary monitoring for early infection detection and health maintenance at home.

- Limitations: sensing cannot perform tasks like turning patients, delivering medications, or replenishing supplies.

- Research imperative: integrate sensing with safe, generalizable robotic manipulation (in-body AI and robotics) to deliver end-to-end caregiving and clinical assistance.

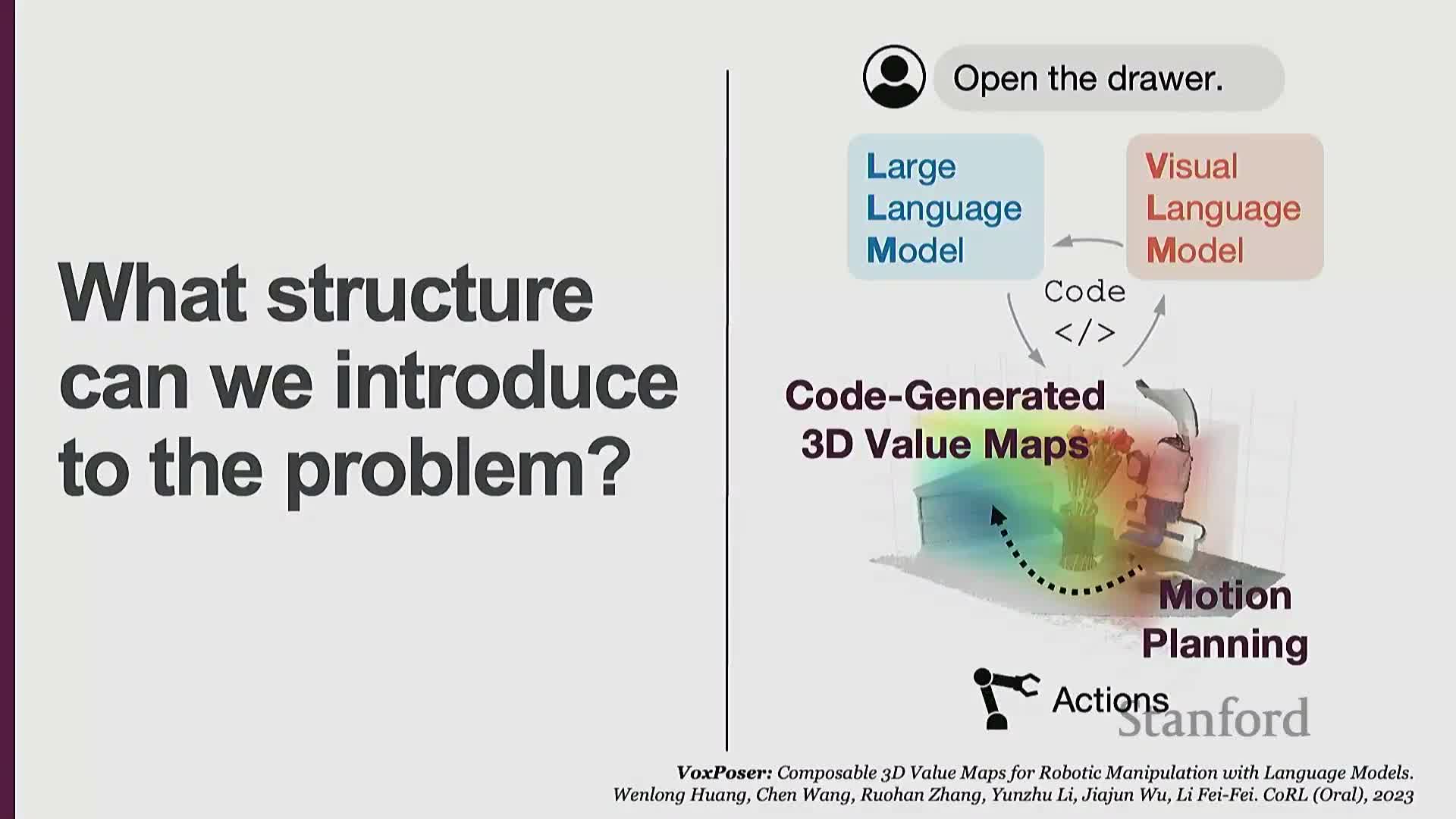

Integrating large language models with visual-language models enables open-instruction robotic manipulation in diverse, unstructured environments.

A practical pipeline for open-instruction robotics composes language models with visual grounding to translate free-form instructions into executable actions:

- Use an LLM to translate human instructions into procedural code or a structured action plan.

- Use a visual-language model (VLM) to detect objects, handles, and affordances in the scene and ground the plan.

- Map semantic instructions and visual detections into motion-planning representations (e.g., heatmaps) that indicate safe and target regions for manipulators.

- Parameterize execution details such as gripper rotation and velocity profiles.

This modular LLM + VLM approach reduces reliance on closed-world task pretraining and supports compositional generalization across articulated object manipulation, obstacle avoidance, and reactive adaptation to online disturbances.

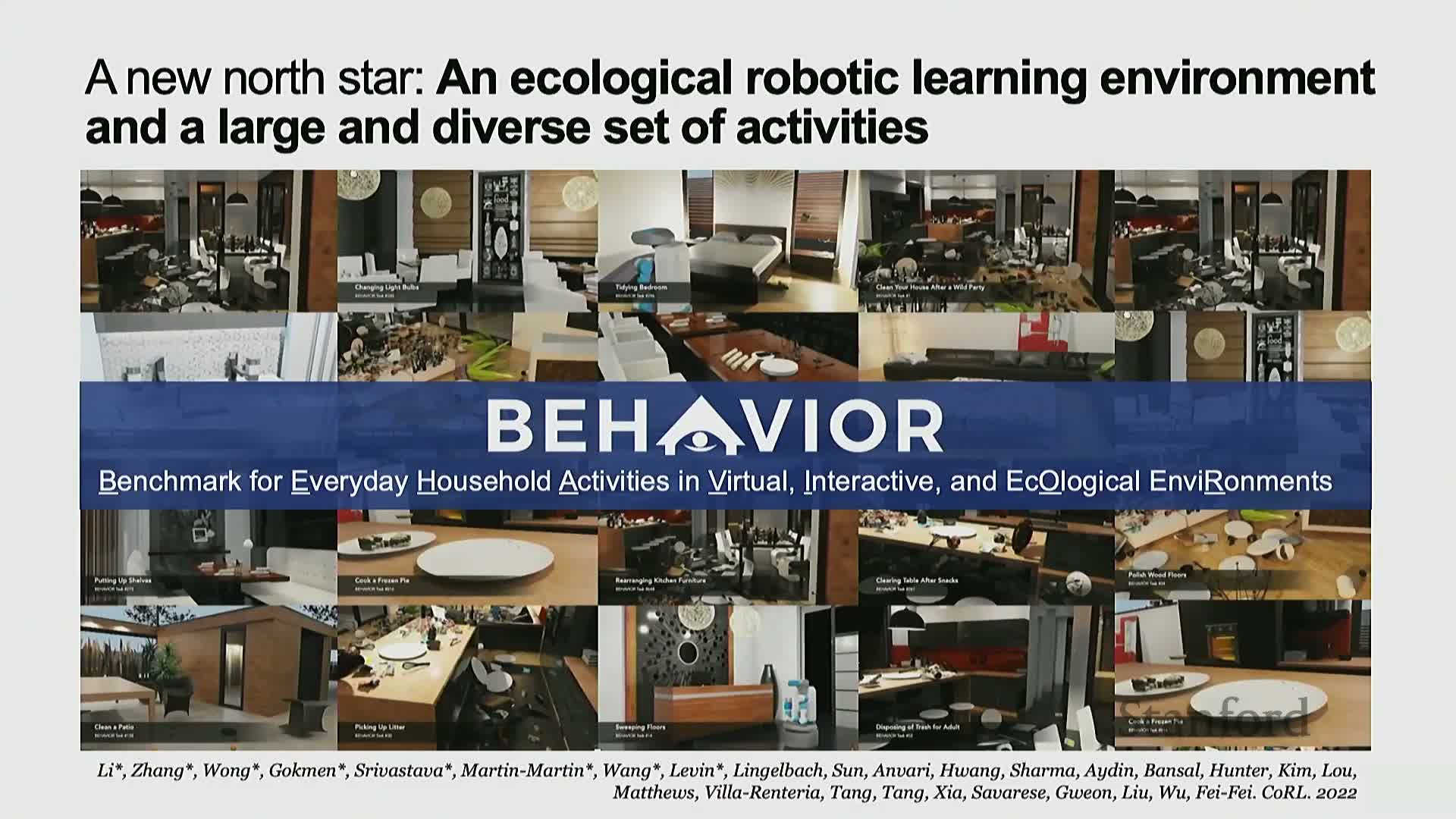

Developing ecological robotic benchmarks requires human-centered task selection and realistic simulation assets for generalization.

A human-centered benchmark pipeline starts by eliciting community or population preferences about which household and service tasks people want robotic help with, aggregating thousands of everyday activities into a prioritized task list.

Realistic ecological benchmarking requires:

- High-fidelity virtual environments created from scanned real-world scenes across diverse locations.

- A large inventory of articulated and deformable 3D object assets.

- Physically accurate simulation of interactions (e.g., cloth, liquids, transparency).

- Perceptually and physically realistic simulators (for example, platforms like NVIDIA Omniverse) validated with human subject studies.

Validated simulators enable training and evaluation regimes that better predict real-world generalization.

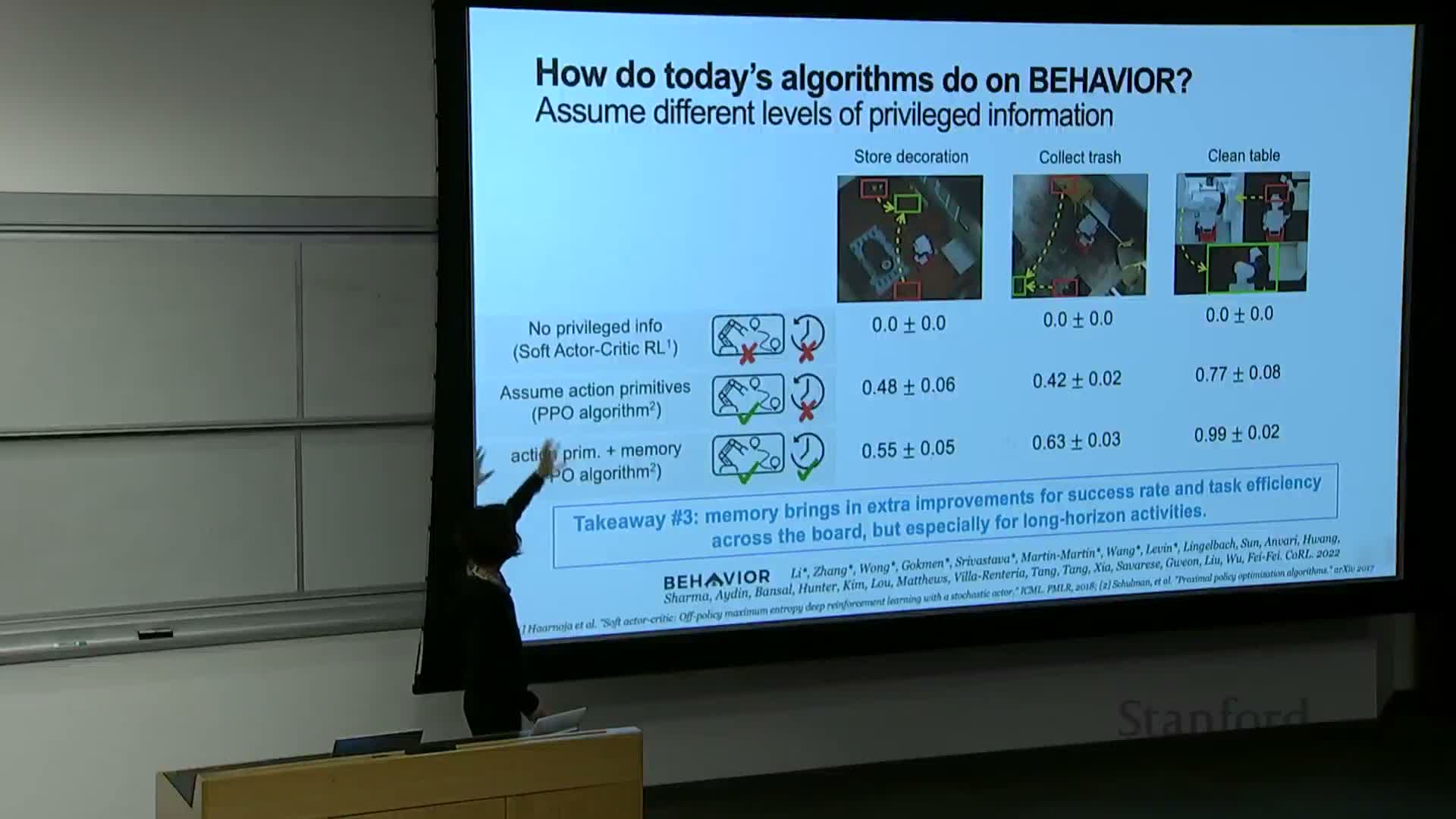

Current robotic algorithms perform poorly on zero-privilege, in-the-wild behavior tasks, revealing a large gap between lab progress and real-world needs.

Benchmark results reveal a large brittleness gap when robots operate without privileged information in realistic, diverse environments:

- Success rates on everyday household behavior tasks are near zero for contemporary algorithms when deployed with no privileged information.

- Performance improves only after adding privileged assumptions (e.g., perfect motion primitives, privileged memory, simplified dynamics), exposing brittleness.

-

Real-to-sim and sim-to-real transfer remain unsolved for multi-step interactive tasks.

- Deployed robots often behave slowly and error-prone in cluttered manipulation scenarios.

These findings motivate a broad research agenda focused on generalization, robust perception-to-action pipelines, and scalable data collection strategies.

Closing perception-action loops includes non-invasive brain interfaces and emphasizes AI as augmentation rather than replacement.

Non-invasive brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) such as EEG can be combined with pretrained action primitives to enable thought-driven control of robotic effectors for assistive tasks.

- Practical demonstrations show sequences of primitive actions triggered by EEG signals accomplishing compound tasks (e.g., meal preparation).

- Requirements: supervised calibration and primitive-level pretraining for each user and task domain.

- Implication: a pathway to empower severely paralyzed individuals with assistive robotics.

Across perception, sensing, and actuation, the overarching principle is to develop AI systems that augment human capabilities, prioritize safety and human values, and provide practical assistance rather than indiscriminate replacement of labor.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: