Stanford CS236- Deep Generative Models I 2023 I Lecture 1 - Introduction

- Course introduction and goals

- Fundamental challenge: making sense of high-dimensional sensory signals

- Generation as a test of understanding (Feynman analogy)

- Rendering, inverse graphics, and latent descriptions

- Statistical generative models and the data-versus-prior spectrum

- Probability distributions as generative simulators and sampling

- Control signals and conditional generation

- Applications: medical imaging and inverse problems

- Historical progress in image generation: GANs to diffusion models

- Text-to-image synthesis and multimodal understanding

- Image editing, sketch-to-image, and interactive control

- Image-based medical reconstructions revisited

- Audio generation and speech models

- Large language models and text generation

- Conditional generation for translation and code synthesis

- Video generation and short-form synthesis

- Generative models for decision-making and imitation learning

- Generative design for molecules and scientific applications

- Risks, misuse, and deepfakes

- Core course topics: representation, learning, and inference

- Models covered and their trade-offs

- Prerequisites, logistics, and resources

- Grading structure, homeworks, and project expectations

Course introduction and goals

This course provides foundational theory and practice for deep generative models, with the objective of teaching how state-of-the-art generative methods used in industry and academia actually work.

It frames the study around building models that can generate images, text, and other modalities, while enabling students to develop, evaluate, and deploy generative systems.

The curriculum emphasizes the core concepts required to design and improve generative architectures, loss functions, and training procedures.

The course situates generative modeling as a timely topic with broad practical impact across multiple application domains.

Fundamental challenge: making sense of high-dimensional sensory signals

High-dimensional signals (images, audio, text) are represented as large arrays or sequences of raw values that often lack immediate semantic structure for decision making.

The central challenge is to map these complex objects to representations that are useful for downstream tasks such as recognition, localization, or reasoning.

This requires:

- Modeling dependencies across many variables.

- Extracting abstractions about objects, materials, motion, and semantics.

Generative modeling offers a pathway to capture such structure by learning underlying distributions and latent factors that explain observed data.

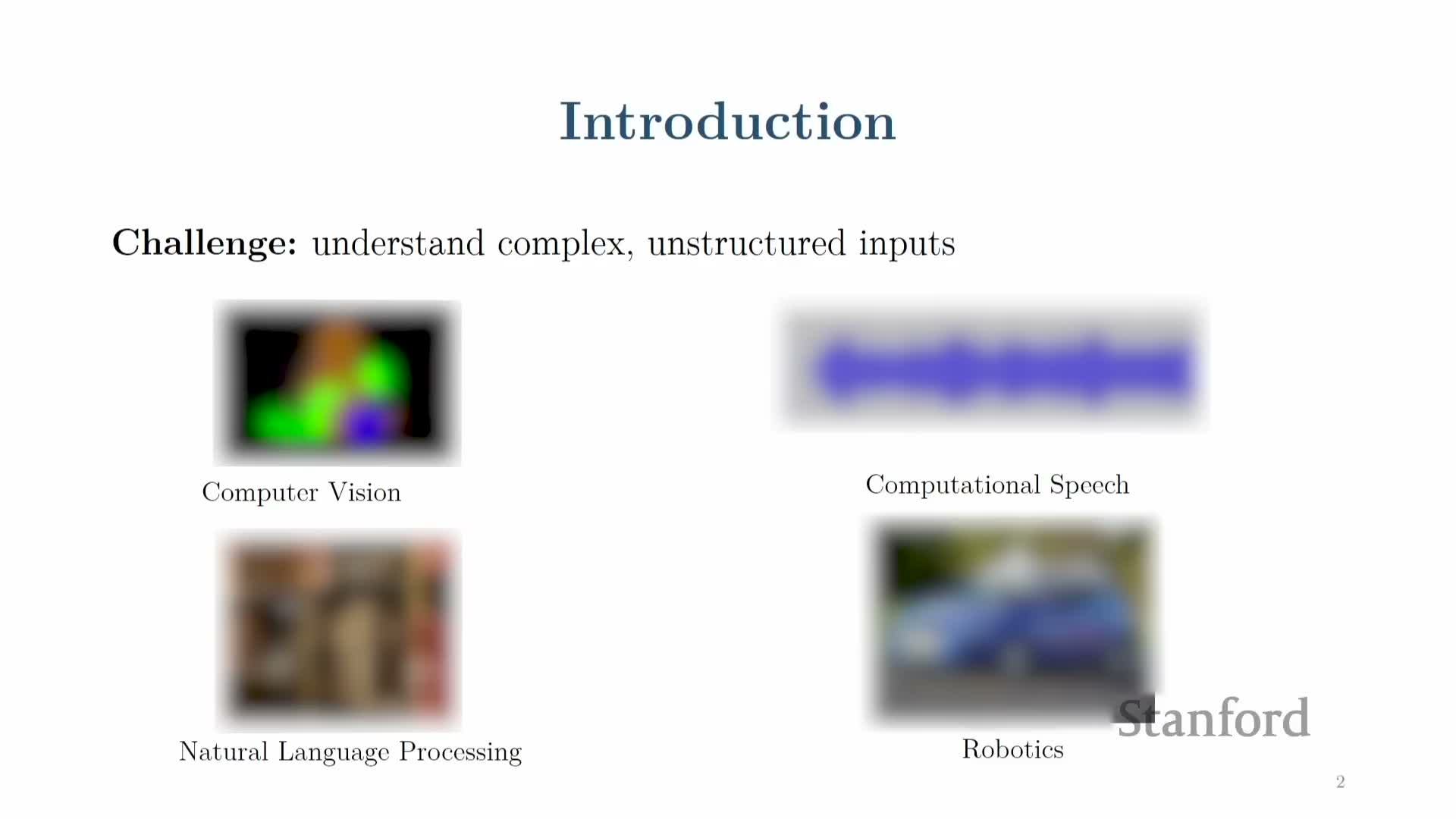

Generation as a test of understanding (Feynman analogy)

Generating data is presented as a principled test of understanding: if a system can produce realistic instances of a concept, it likely captures the concept’s essential structure.

This perspective motivates building models that can synthesize images or text, since synthesis requires internalizing grammar, semantics, and common-sense relations.

The contrapositive is informative too: inability to generate realistic data indicates incomplete understanding.

This philosophical stance underlies the emphasis on generative models as both explanatory tools and practical simulators for AI.

Rendering, inverse graphics, and latent descriptions

Computer graphics exemplifies a forward generative process that maps high-level scene descriptions (objects, materials, viewpoint) to images; inverting that process gives the interpretation of vision as inverse graphics.

Statistical generative models follow a similar structure by defining latent variables that encode scene or semantic descriptions which, when rendered, produce observable signals.

Inferring latent variables from raw inputs yields representations useful for downstream tasks and provides a conceptual bridge between graphics-based modeling and data-driven probabilistic approaches.

The course focuses on statistical, data-driven incarnations of these ideas rather than traditional physics-based renderers.

Statistical generative models and the data-versus-prior spectrum

Generative models are formalized as probability distributions over observations that combine data-driven learning with prior knowledge (architectural biases, loss choices).

There is a spectrum of approaches:

-

Physics-rich modeling (graphics) on one end.

-

Highly data-driven approaches that minimize hand-designed priors on the other.

Priors manifest in choices such as:

- Neural network architectures and inductive biases.

-

Optimization algorithms and loss formulations.

These priors shape sample efficiency and generalization. The practical focus is on methods that leverage substantial data to learn flexible probabilistic models for images, text, and other modalities.

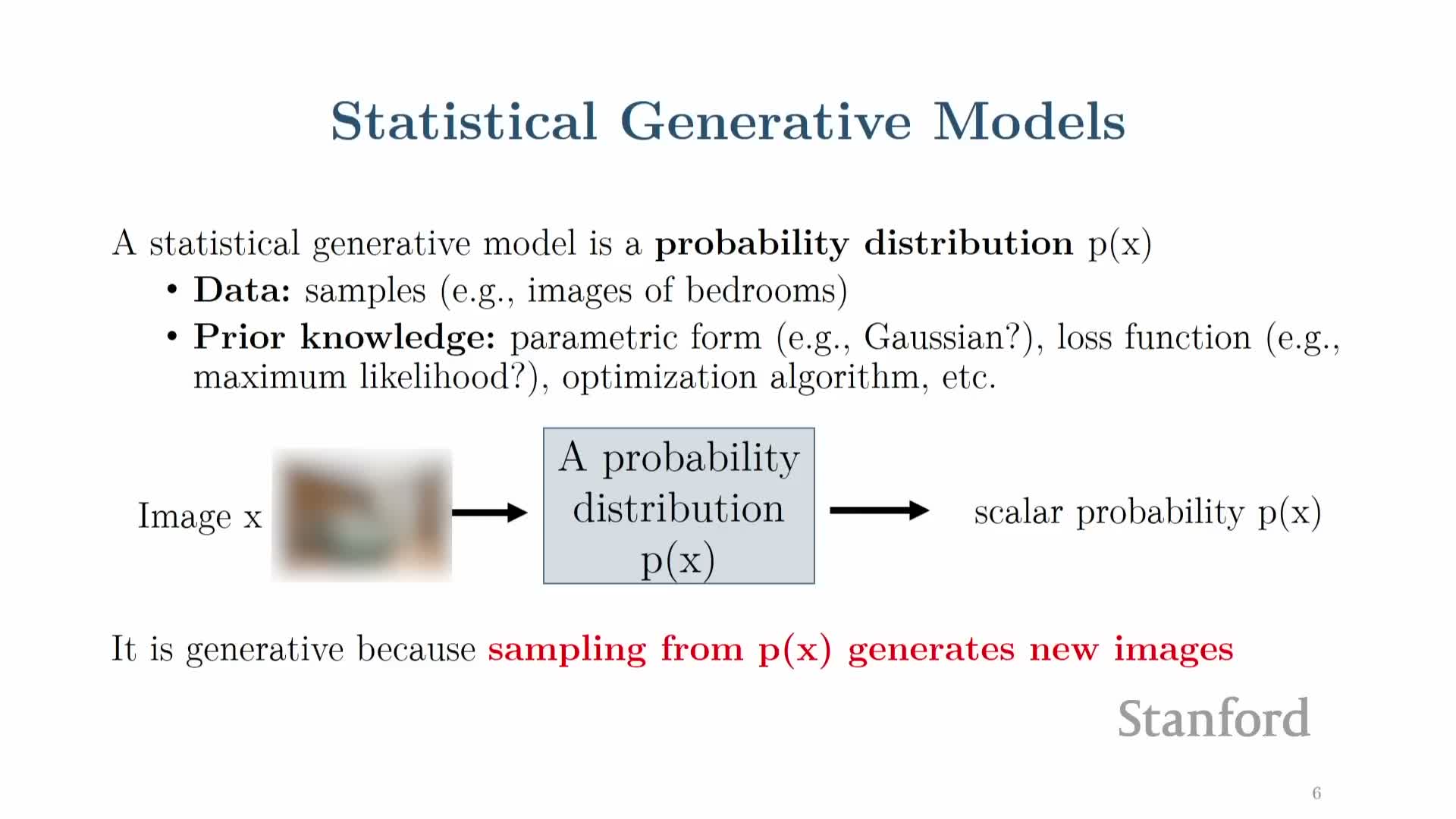

Probability distributions as generative simulators and sampling

A generative model defines a function that assigns probabilities to observations and can act as a data simulator by sampling from the learned distribution.

Key points about learning and use:

-

Learning fits a model distribution so that samples resemble the empirical data distribution.

- The learned model can be queried for likelihood-based judgments to assess how typical or atypical an observation is (useful for outlier detection).

- In practice, sampling methods and the ability to efficiently generate diverse outputs are central design concerns.

Control signals and conditional generation

Generative models can be controlled by conditioning on auxiliary inputs so that sampling produces outputs satisfying user-provided constraints.

Examples of control signals:

-

Text captions, sketches, low-resolution or grayscale images, and sensor measurements.

Benefits of conditioning:

- Enables applications such as text-to-image synthesis, colorization, and translation.

- Transforms unconstrained sampling into controlled simulation, facilitating guided content creation and solving inverse problems.

Implementation note: conditioning is typically incorporated into the model architecture and/or the training objective to ensure fidelity to the control input.

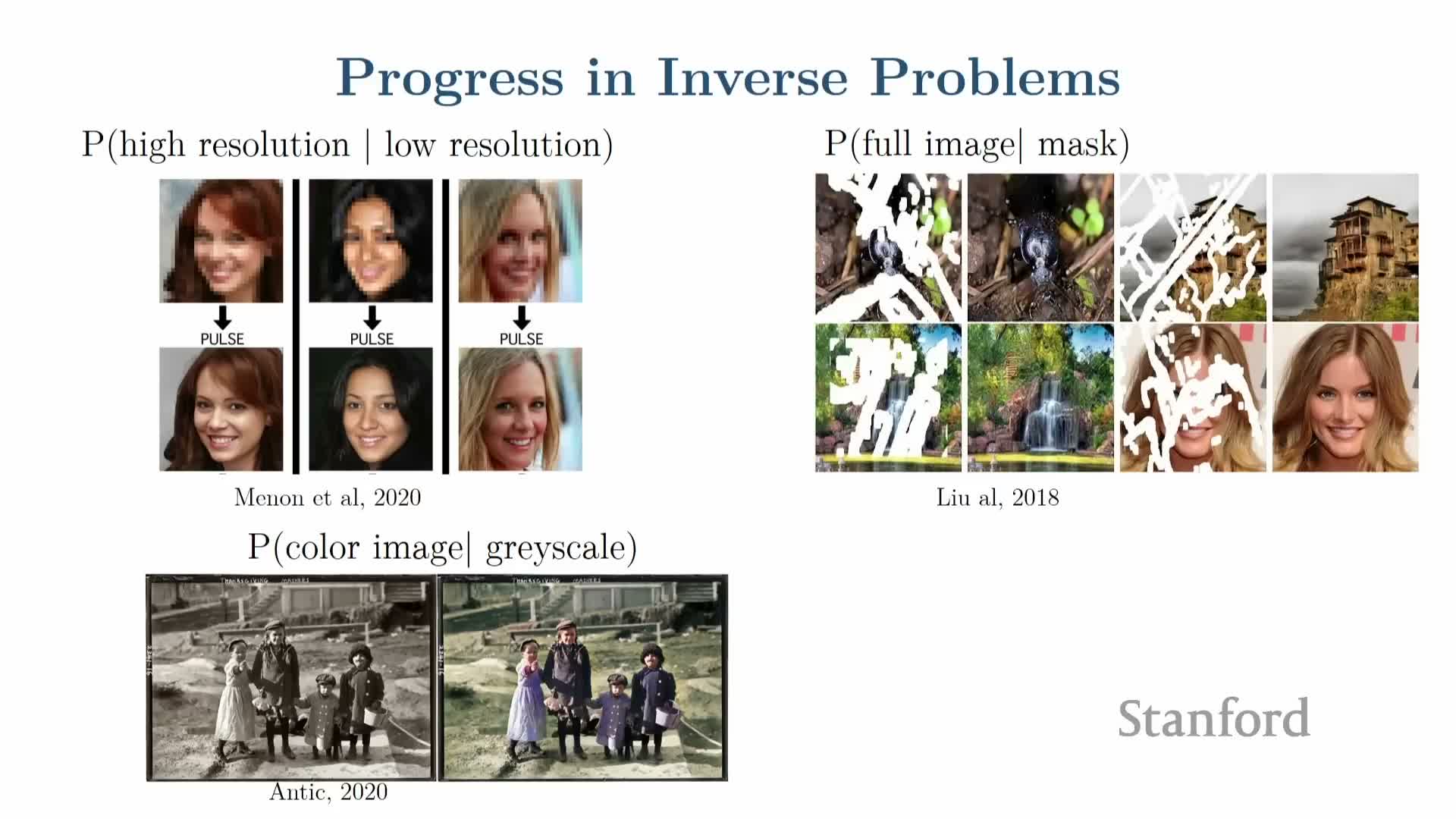

Applications: medical imaging and inverse problems

Generative models substantially improve inverse imaging tasks by encoding priors about plausible signals and enabling reconstruction from limited or noisy measurements.

Applications and benefits:

- In medical imaging, conditional generative models can reconstruct higher-quality CT or MRI images from fewer measurements or lower radiation doses, improving patient safety and throughput.

- Tasks like super-resolution, denoising, and inpainting are natural inverse problems where learned generative priors supply missing information and enforce global consistency.

These applications illustrate how generative modeling can reduce measurement costs while preserving clinically or operationally relevant details.

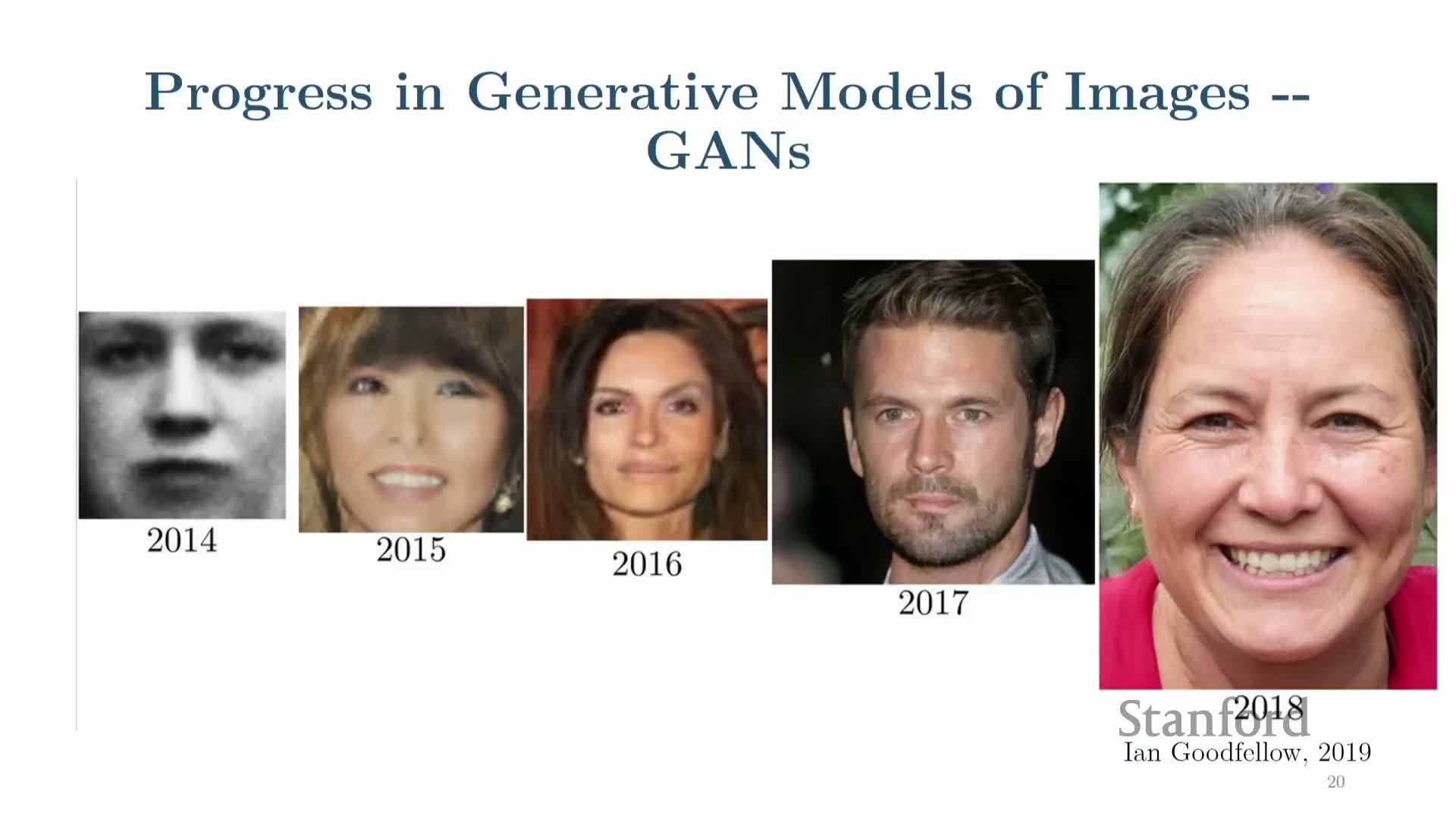

Historical progress in image generation: GANs to diffusion models

Image generation quality has advanced rapidly from early low-resolution outputs to photo-realistic high-resolution images via successive model classes.

Notable model families and their impacts:

-

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) accelerated perceptual realism by optimizing adversarial training objectives that favor sample fidelity.

-

Score-based diffusion models and related formulations pushed state-of-the-art further by modeling score functions or denoising processes, enabling stable, high-fidelity synthesis and principled likelihood interpretations.

Each family introduces trade-offs in training stability, sample quality, and likelihood tractability.

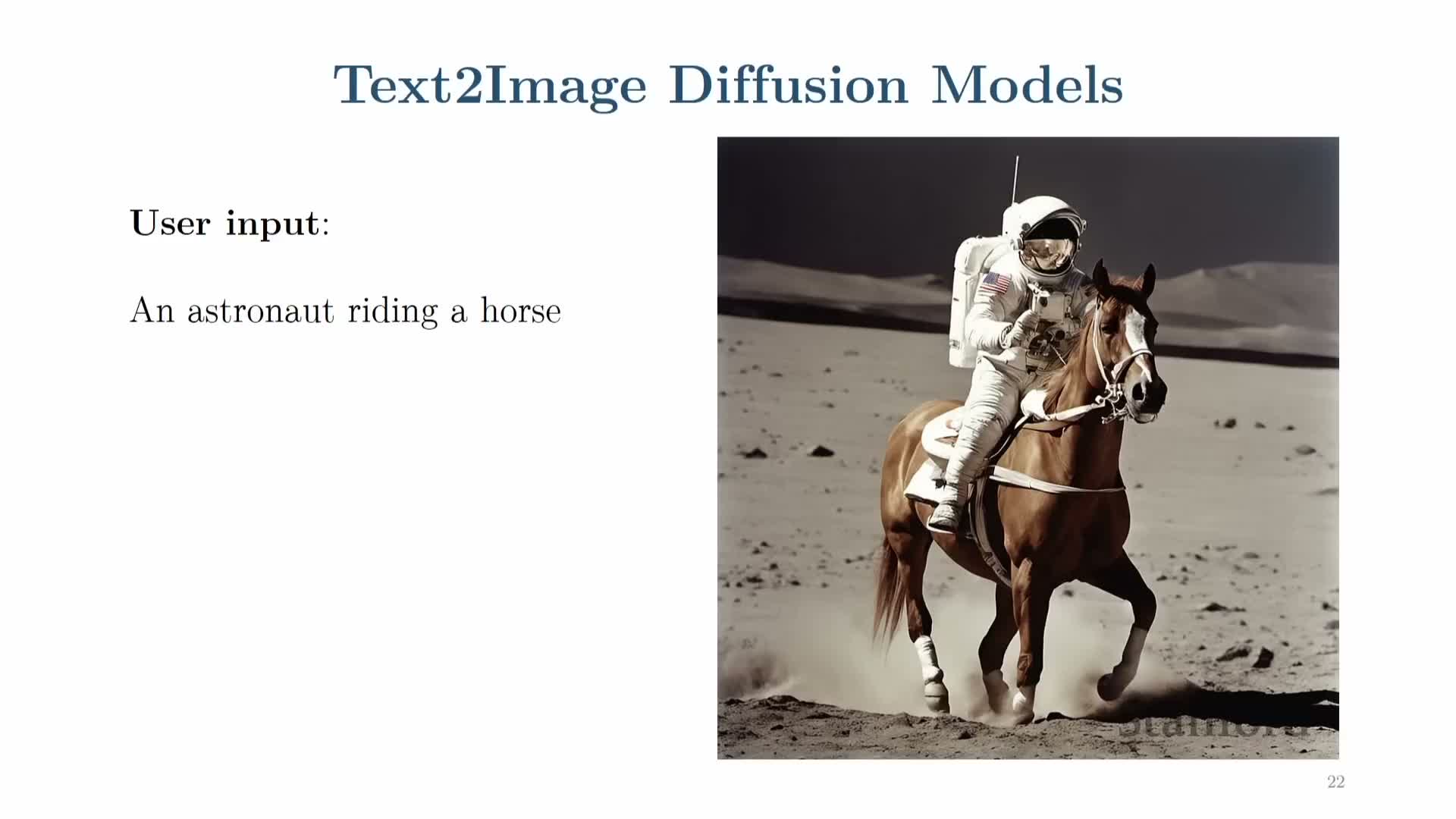

Text-to-image synthesis and multimodal understanding

Modern diffusion-based generative models enable conditioning on natural language to synthesize coherent, novel images that combine concepts not typically observed together in training data.

Key capabilities:

- Text-conditioned models learn joint language-vision representations that support compositionality (e.g., producing an astronaut riding a horse even when the combination is rare).

- This multimodal capability reflects the model’s ability to internalize semantics of objects and relations, underpinning contemporary text-to-image systems used in creative and production settings.

Stochastic sampling from the learned conditional distribution yields diverse outputs for a single prompt.

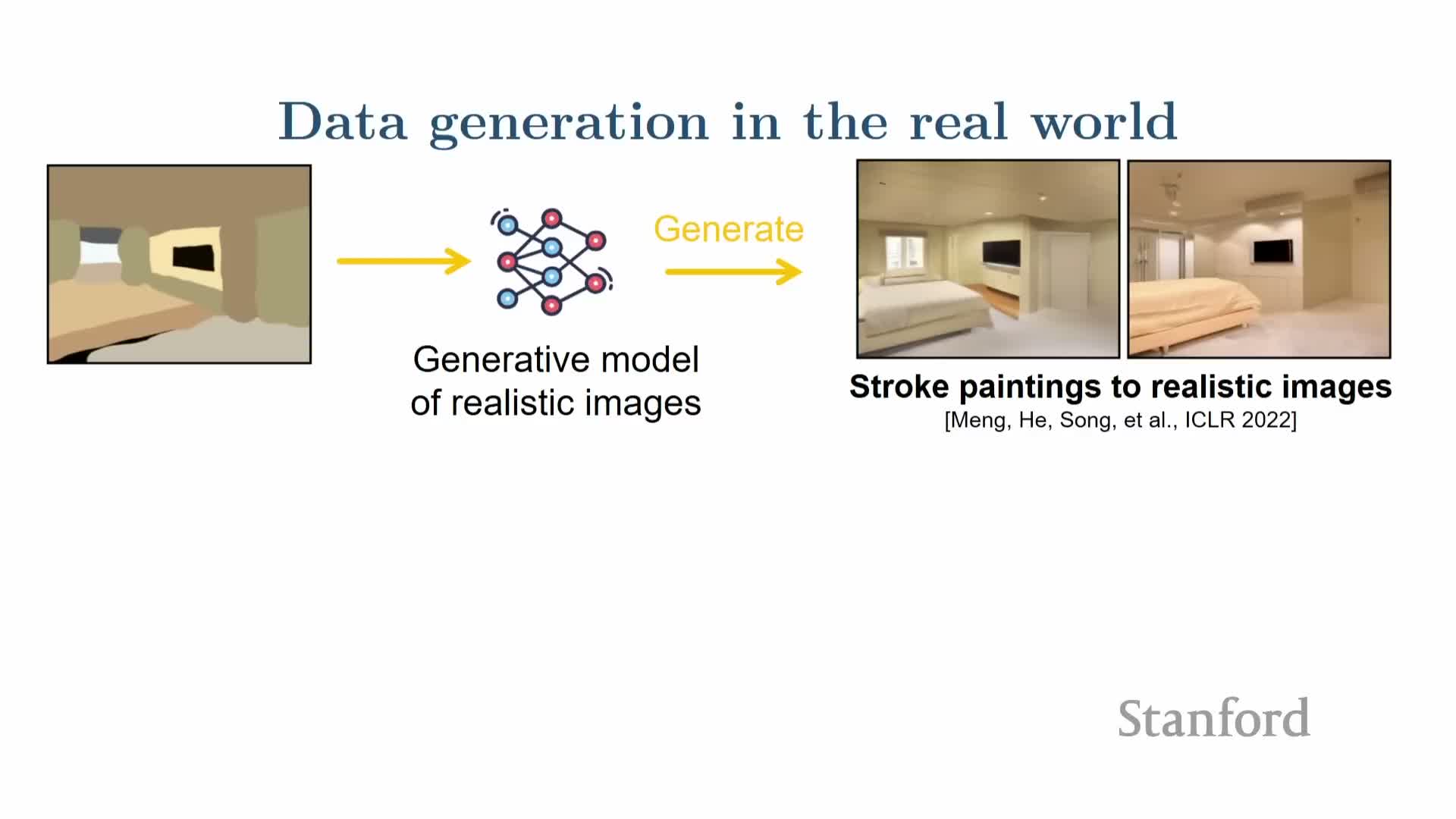

Image editing, sketch-to-image, and interactive control

Generative models support diverse editing interfaces, including sketch-to-image refinement, stroke-based editing, and natural-language-guided transformations.

Practical behaviors:

- By conditioning on partial or structured inputs, models can preserve user-provided layout or content while rendering photorealistic details and stylistic changes.

- Applications include style transfer, pose editing, object insertion, and semantic edits (for example, “spread the wings” or “make the birds kiss”).

These conditional editing capabilities rely on architectures and loss functions that balance adherence to control signals with generative realism.

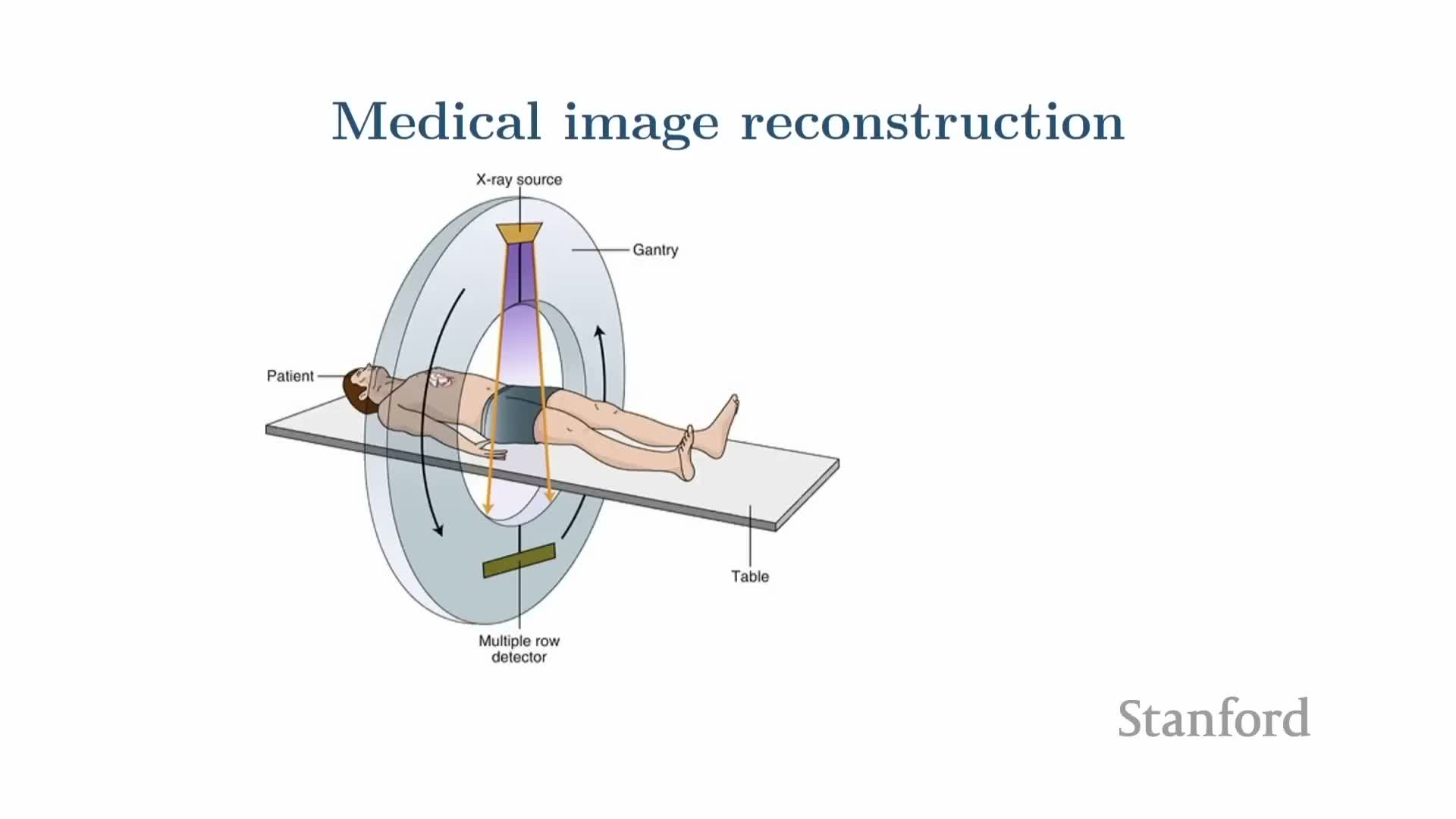

Image-based medical reconstructions revisited

The same conditional generative techniques used for image editing translate to medical reconstruction tasks, where device measurements act as conditioning signals.

Implications:

- Modeling the conditional distribution over plausible medical images given partial sensor measurements permits aggressive measurement reduction (e.g., fewer CT projections) while retaining diagnostically useful reconstructions.

- This is formally analogous to inpainting or super-resolution in visual domains and highlights cross-domain applicability of generative priors.

Deployment caveat: successful clinical use requires careful validation to ensure safety and robustness to distributional shifts.

Audio generation and speech models

Generative modeling of audio, especially text-to-speech, has progressed from autoregressive waveform models (e.g., WaveNet) to more recent diffusion- and transformer-based systems that produce highly realistic, expressive speech.

Typical architectures and tasks:

- Modern systems often predict sequences of audio tokens or parameters conditioned on text and use multi-stage architectures (acoustic model + vocoder) for high fidelity.

- These models enable inverse audio tasks such as audio super-resolution and restoration by conditioning on low-quality inputs.

The techniques parallel image-domain methods in modeling sequential dependence and leveraging conditional generation.

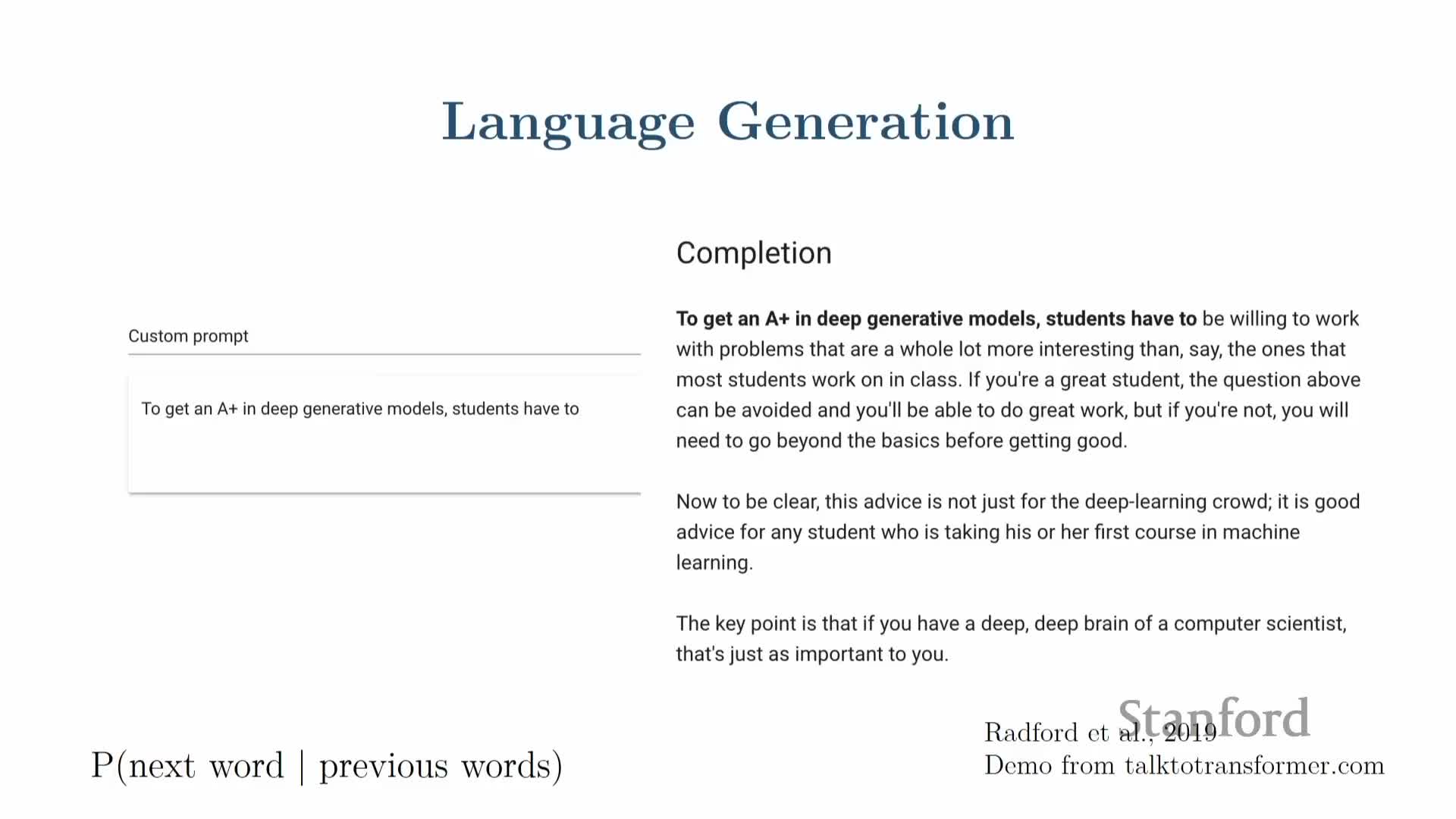

Large language models and text generation

Large language models (LLMs) model probability distributions over token sequences and generate fluent text via autoregressive sampling conditioned on prompts.

Key aspects:

- Training on massive corpora yields models that capture grammar, facts, and common-sense regularities, enabling prompt completion, question answering, translation, and code generation.

- LLM behavior can be interpreted as learning which continuations of a prompt are high-probability under the data distribution; conditioning lets these models perform diverse NLP tasks.

Evaluation emphasizes coherence, factuality, and controllability of generated outputs.

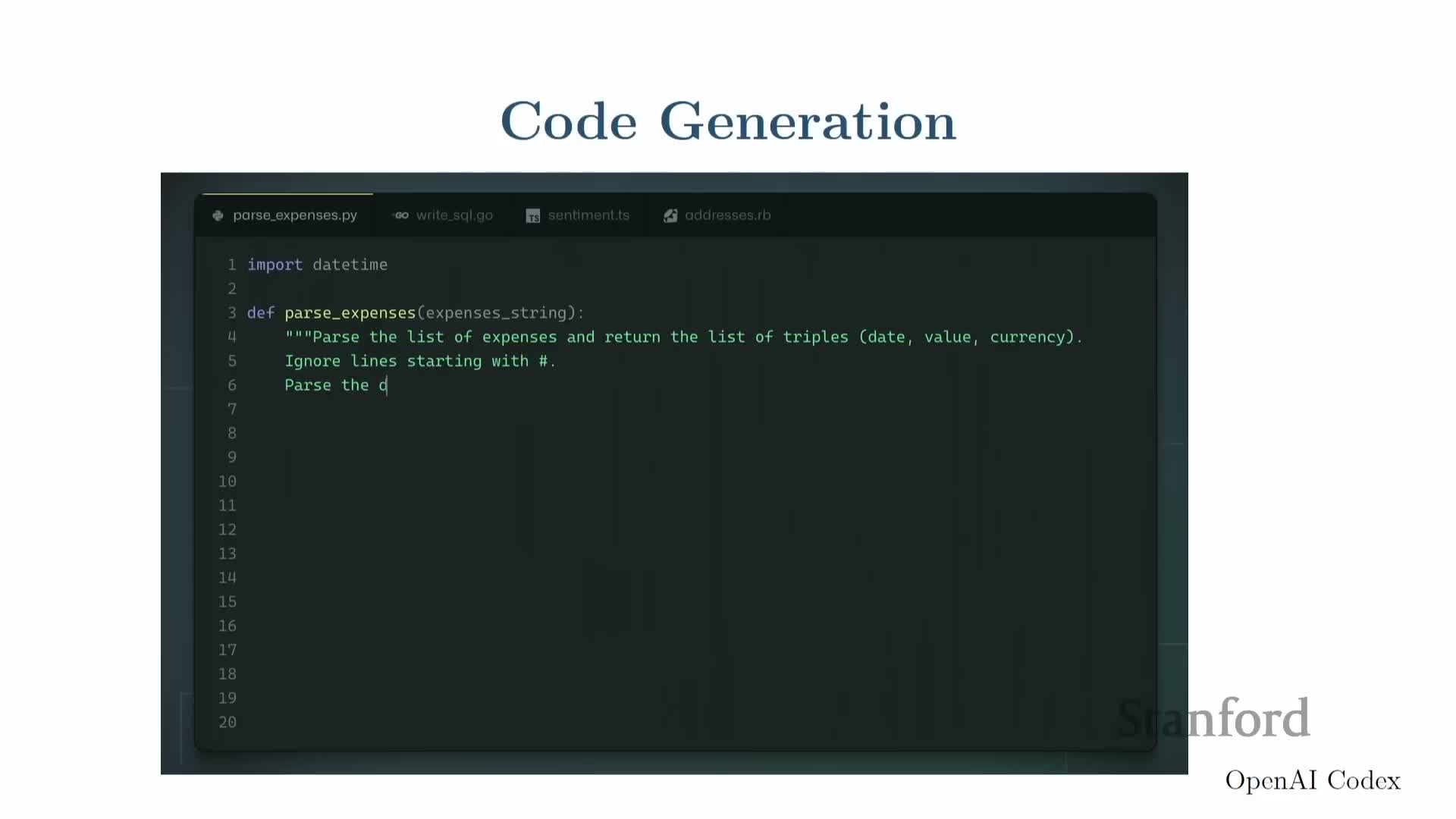

Conditional generation for translation and code synthesis

Generative models that condition on structured or cross-modal inputs form the basis for machine translation and program synthesis by mapping between input modalities.

Examples:

- In translation, a model generates target-language text conditioned on source-language input; improvements in generative modeling directly translate to better translation quality.

- For code synthesis, language models trained on code can generate syntactically and semantically coherent program fragments from natural-language descriptions, enabling autocompletion and developer assistance.

These applications illustrate the versatility of conditional generation across structured output spaces.

Video generation and short-form synthesis

Video synthesis treats a video as a temporal stack of image frames and extends image generative methods to capture coherent dynamics across time.

Current status and challenges:

- Systems produce short, caption-conditioned clips with notable spatial quality and rudimentary temporal coherence; stitching or post-processing can extend these primitives to longer narratives.

- Video generation adds modeling challenges such as temporal consistency, motion modeling, and longer-range dependencies.

Video generation benefits from multimodal conditioning (text, seed images, audio) and is an active area of ongoing progress with implications for content creation, simulation, and entertainment.

Generative models for decision-making and imitation learning

Generative techniques apply to sequential decision problems by modeling distributions over action sequences or trajectories that achieve desirable goals.

Connections and applications:

- In imitation learning, models learn to generate behavior conditioned on observations by training on demonstrations, enabling policy synthesis for tasks like driving or manipulation.

-

Diffusion formulations and other generative priors can propose plausible trajectories that respect dynamics and constraints, facilitating planning and control.

This perspective unifies generative sampling with policy generation and highlights cross-cutting methods between perception and control.

Generative design for molecules and scientific applications

Generative models are increasingly used to propose molecular structures, protein sequences, and catalysts by learning distributions over chemical or biological objects with desirable properties.

Approaches and considerations:

- Conditioning, objective-guided sampling, or latent-space optimization enables candidate design that targets binding affinity, structural stability, or catalytic activity.

- Model families (autoregressive, diffusion, latent-variable) are adapted to discrete and graph-structured domains, with attention to domain-specific representations and evaluation criteria.

These applications illustrate generative modeling’s potential to accelerate discovery in chemistry, biology, and materials science.

Risks, misuse, and deepfakes

High-quality generative systems create realistic synthetic content that can be difficult to distinguish from authentic material, raising concerns about misuse such as deepfakes and misinformation.

Mitigation strategies include:

- Technical safeguards and provenance mechanisms.

-

Detection methods and complementary policy interventions.

Responsible deployment requires evaluating societal impacts, understanding failure modes, and designing models with robustness and accountability in mind. Ethical considerations are integral to both research agendas and practical applications in generative modeling.

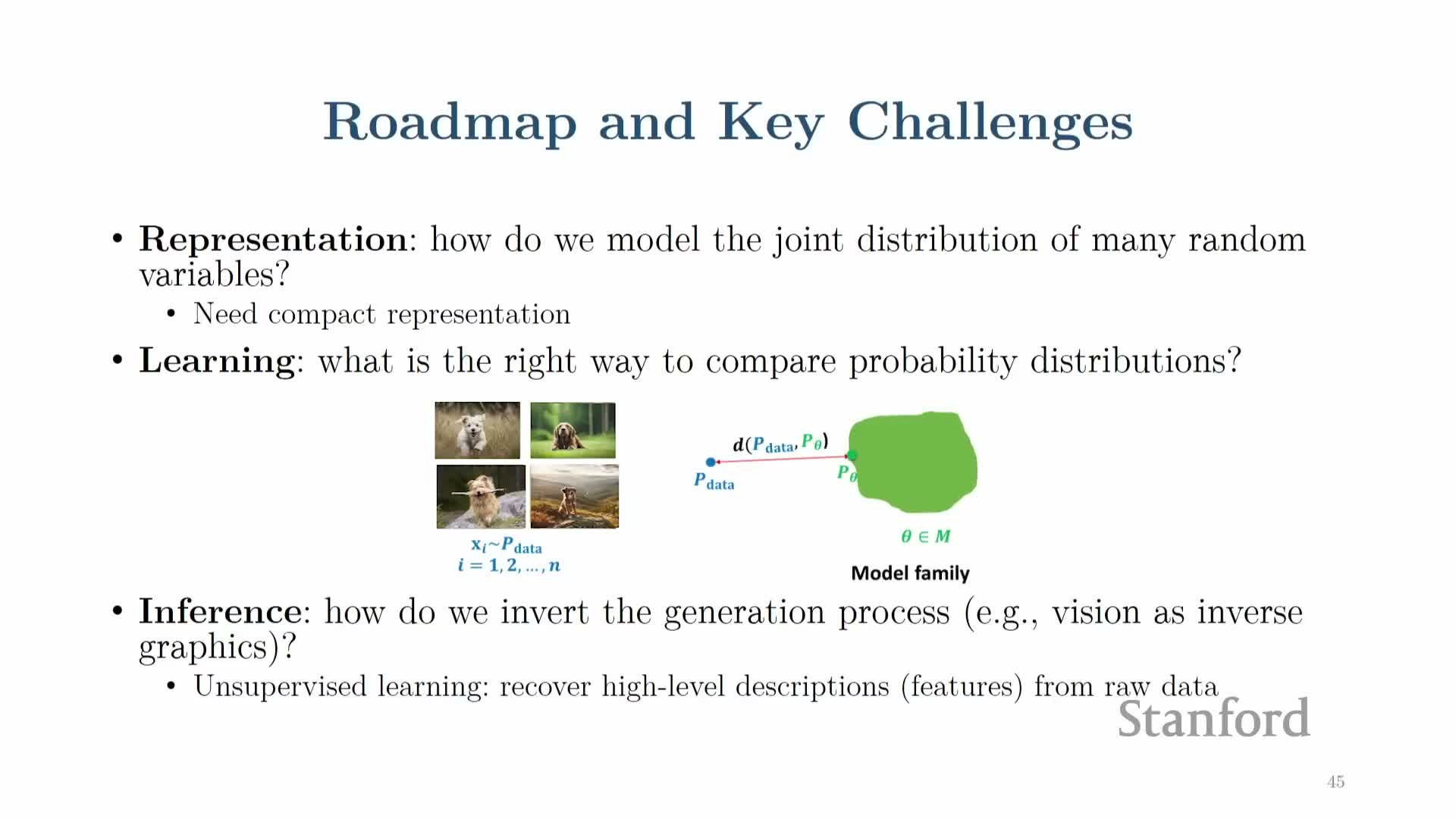

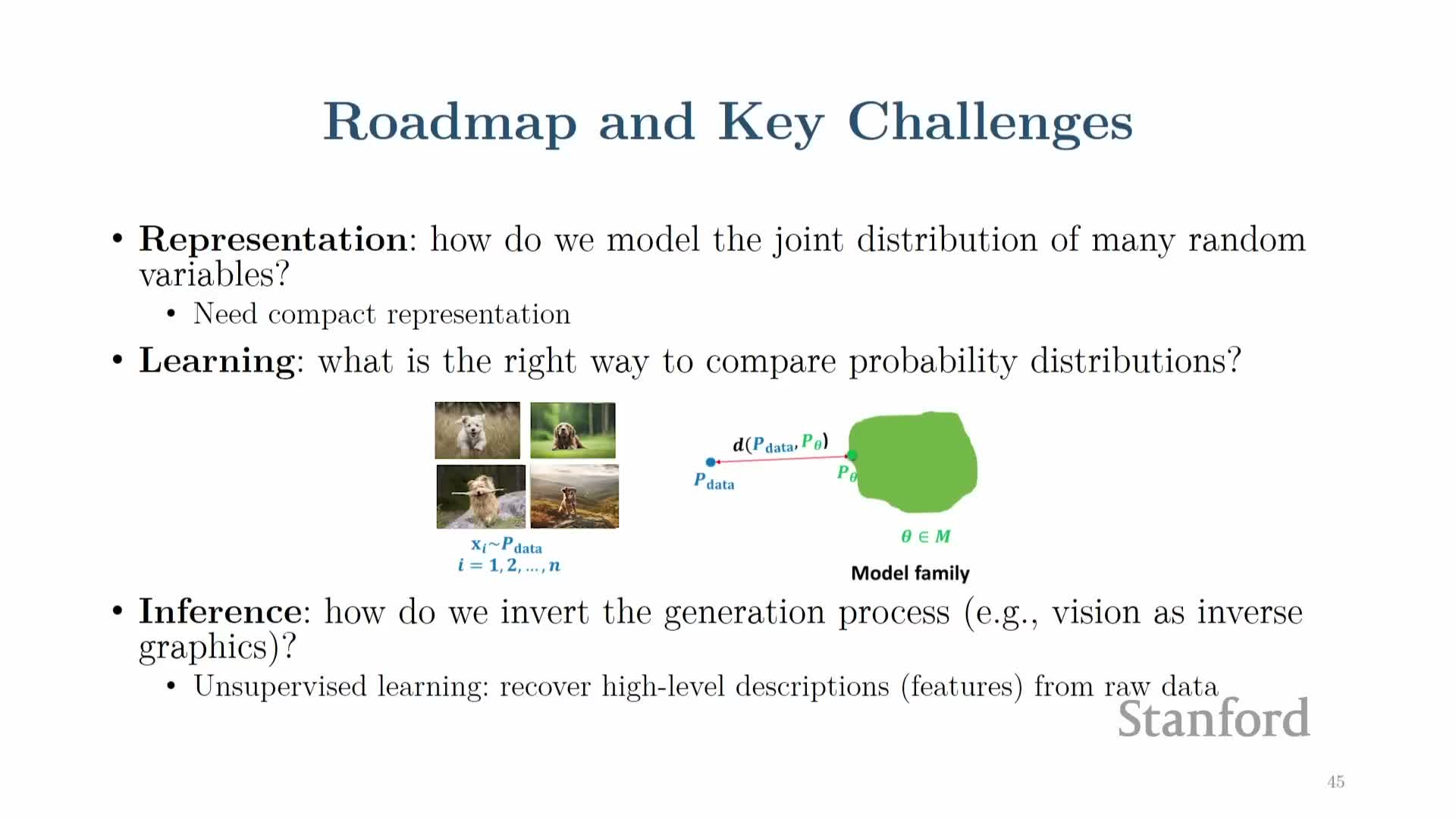

Core course topics: representation, learning, and inference

The course centers on three interrelated pillars:

-

Representation of probability distributions

- Scalable parameterizations of high-dimensional distributions using neural networks.

- Factorization strategies and latent-variable designs.

- Scalable parameterizations of high-dimensional distributions using neural networks.

-

Learning methods for fitting generative models to data

- Objective selection, divergence measures, and optimization methods across model families.

- Objective selection, divergence measures, and optimization methods across model families.

-

Inference techniques for sampling and extracting latent representations

- Sampling algorithms, conditional generation, and latent-variable inversion.

- Sampling algorithms, conditional generation, and latent-variable inversion.

Mastery of these pillars enables the design and analysis of generative systems across modalities.

Models covered and their trade-offs

The curriculum covers major generative model classes and their trade-offs:

-

Autoregressive and flow models with tractable likelihoods.

-

Latent-variable models trained with variational inference.

-

Implicit models (e.g., GANs) that favor efficient sampling but lack explicit likelihoods.

-

Energy-based and diffusion models that offer strong sample quality and theoretical connections.

Each family exhibits different properties in terms of expressivity, ease of training, sampling efficiency, and likelihood access. The course examines training criteria (e.g., maximum likelihood, adversarial losses, score matching) and evaluation metrics appropriate to each class.

Prerequisites, logistics, and resources

Successful participation requires familiarity with:

-

Basic probability, calculus, and linear algebra.

- Core machine learning concepts.

- Programming proficiency in Python and experience with deep learning frameworks such as PyTorch.

Course support and resources:

- Lecture notes and reading references (including the Deep Learning book).

- Staff support via teaching assistants and office hours; students should monitor the course website for updates.

Background materials and review content are provided, but substantial prior exposure to probabilistic modeling and optimization is recommended. Practical assignments and projects require computational resources and basic cloud familiarity.

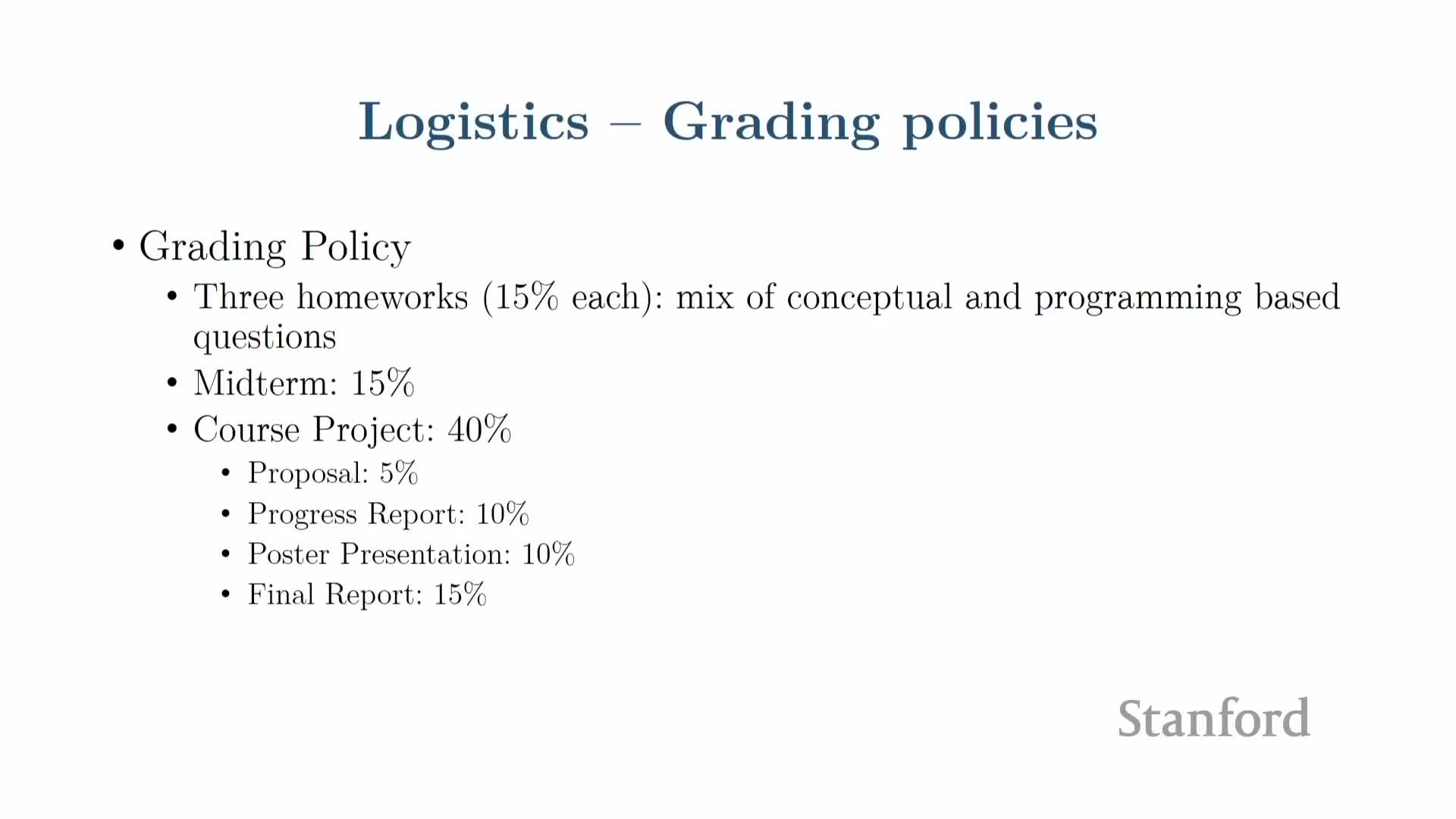

Grading structure, homeworks, and project expectations

Assessments include:

- Multiple homework assignments combining theory and programming.

- An in-person midterm.

- A substantial team-based project that constitutes a significant portion of the grade.

Project structure and deliverables:

-

Proposal

-

Progress report

-

Poster

-

Final report

Projects typically involve applying or extending generative models to new datasets, comparing methods, or contributing methodological improvements. The project emphasizes hands-on experimentation, potential for publishable results, and exploration of open research questions. Limited cloud credits and suggested project ideas are made available to support student work.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: