CS336 Lecture 1 - Overview and Tokenization

- Motivation for building language models from scratch

- Industrialization of frontier models limits access to large-scale details

- Scale-dependent differences and emergence in model behavior

- Three types of knowledge required for language-model research

- Empirical experimentation often outweighs handwavy explanations

- The ‘bitter lesson’ reframed: algorithms at scale and efficiency matter

- Research framing: maximize accuracy per resource and historical landscape

- Executable, code-embedded lectures as a teaching artifact

- Course logistics, prerequisites, and expectations

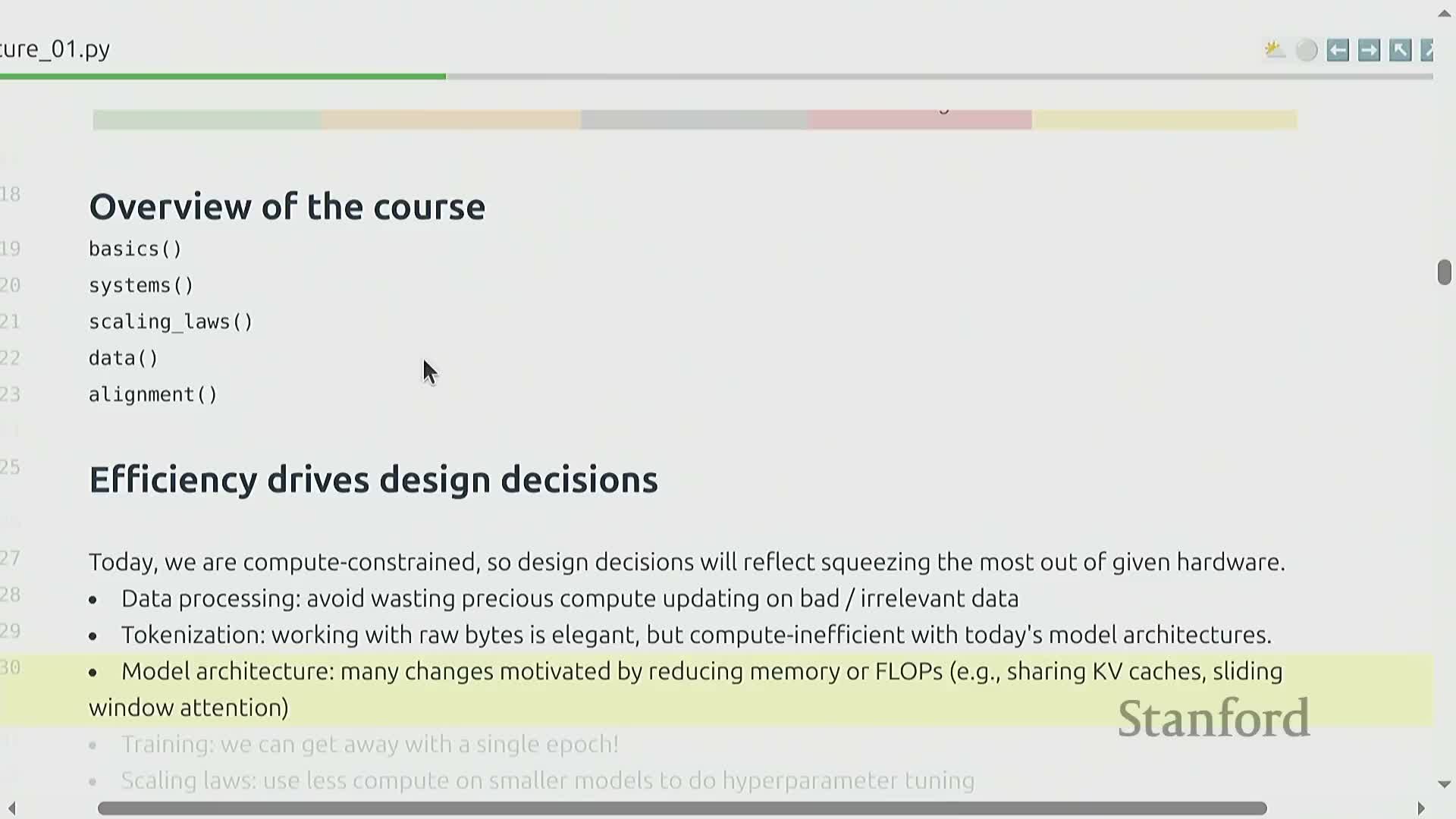

- Course structure and the ‘efficiency-first’ design philosophy

- Basics unit: tokenizer, transformer architecture, and training loop

- Systems unit: kernels, multi-GPU parallelism, and inference optimization

- Scaling laws unit: choosing model size and training allocations under a FLOPs budget

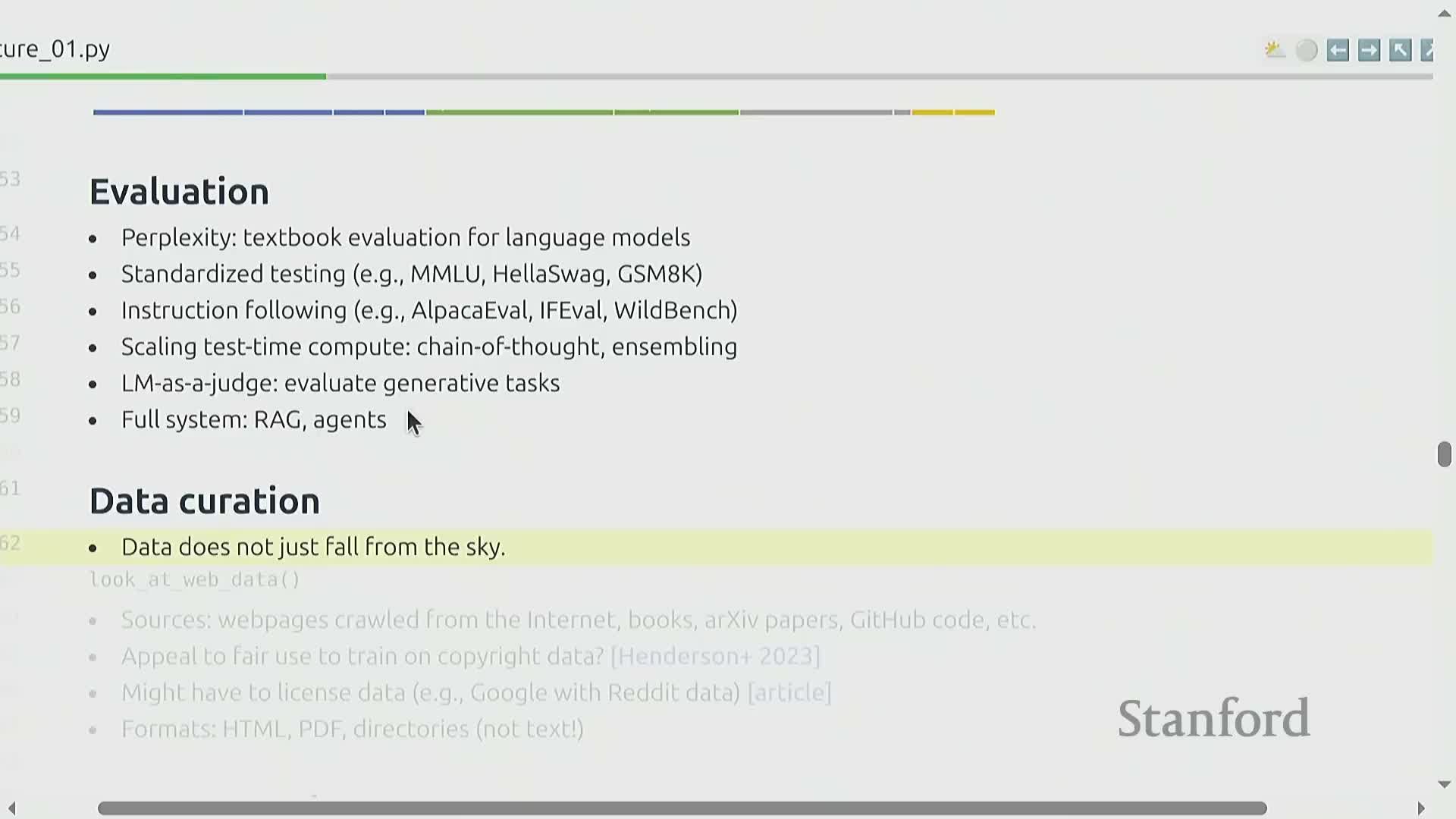

- Data unit: evaluation, curation, and preprocessing of web-scale sources

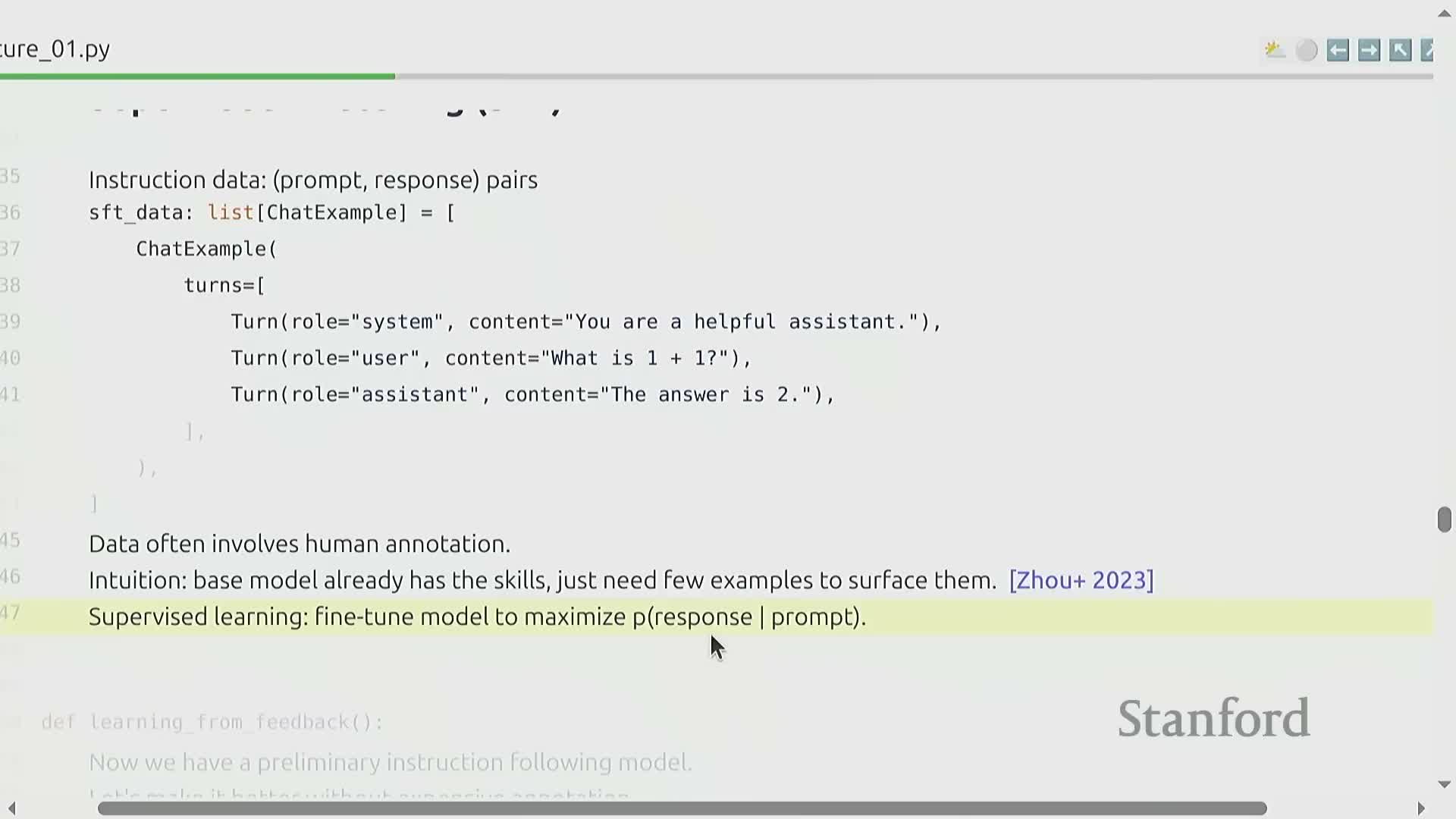

- Alignment unit: supervised fine-tuning and learning from feedback

- Efficiency-first recap and regime-dependent design choices

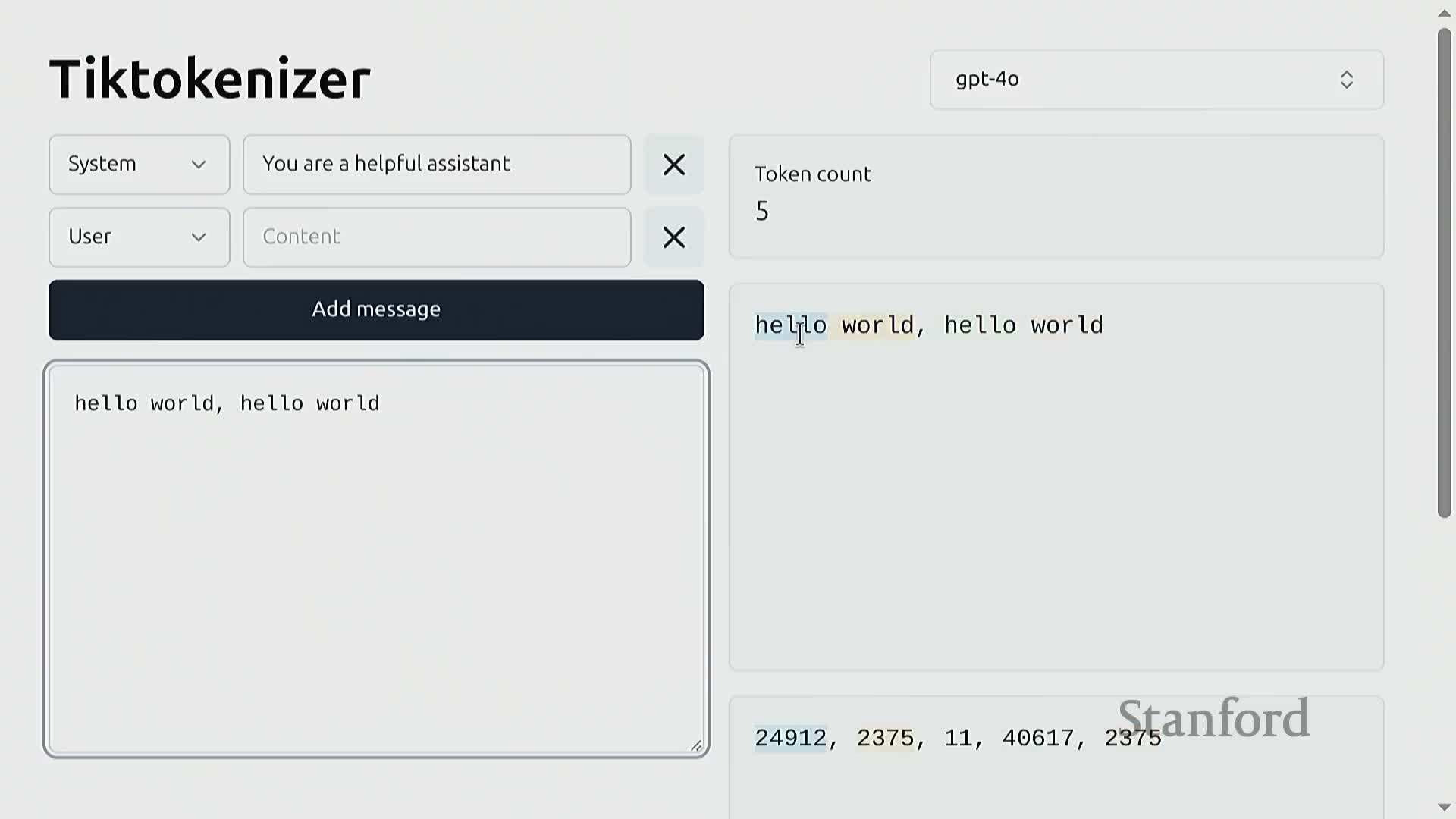

- Tokenization overview and practical tokenizer behaviors

- Primitive tokenization schemes and their trade-offs

- Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): algorithm and training procedure

- BPE implementation considerations and tokenizer deployment

Motivation for building language models from scratch

Building language models from first principles is motivated by the need to retain deep technical understanding across the modeling, data, and systems stack—this end-to-end knowledge enables fundamental research that requires tearing up abstractions and co-designing multiple components.

While high-level prompting and API access have accelerated research productivity, those abstractions are leaky and can obscure crucial system–data interactions.

The course therefore aims to teach the raw mechanics required for rigorous research and engineering by having participants implement components themselves.

-

Who this is for: participants who intend to push core innovations rather than only apply existing high-level APIs.

- Course emphasis: hands-on implementation to expose and reason about the underlying system and data interactions that high-level abstractions often hide.

Industrialization of frontier models limits access to large-scale details

Frontier language models have grown extremely large and expensive to develop, with reported parameter counts, training costs, and cluster sizes far beyond typical academic resources—many production teams also do not disclose internal engineering or data details.

This industrialization places the highest-performing architectures and practices behind proprietary boundaries, constraining reproducibility and direct experimentation at scale.

-

As a result, coursework and research that aim to replicate or fully study frontier phenomena must focus on smaller-scale models and be precise about what can (and cannot) be learned in that regime.

-

The scarcity of public implementation and dataset details motivates careful study of:

-

Accessible algorithms that perform well within constrained compute and data budgets

-

System optimizations that improve efficiency and allow larger experiments on limited infrastructure

-

Principled extrapolation methods for interpreting small-scale results and estimating behavior at frontier scale

-

Accessible algorithms that perform well within constrained compute and data budgets

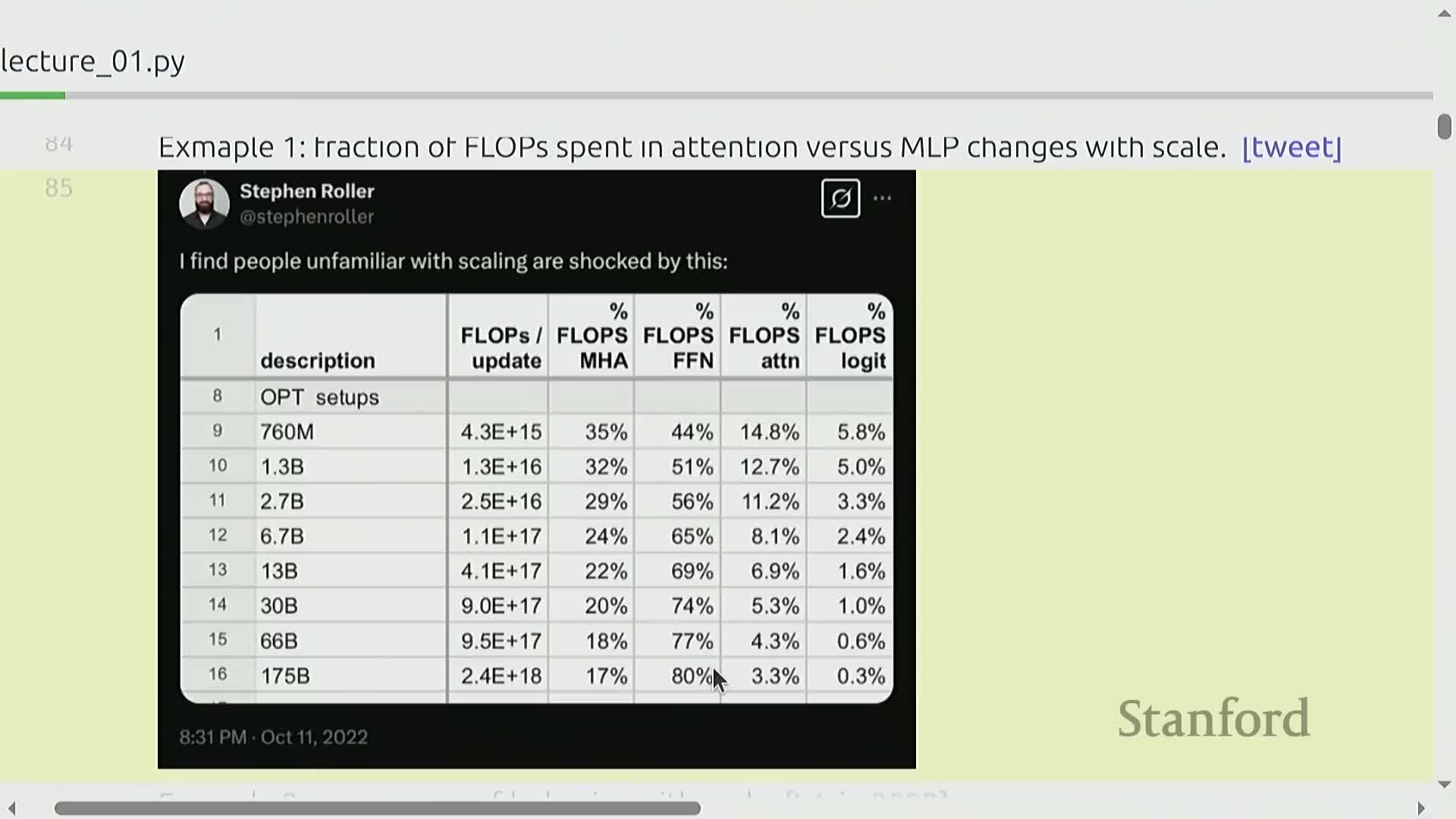

Scale-dependent differences and emergence in model behavior

Model behavior and resource-allocation trade-offs change nonlinearly with scale.

As model size grows, the relative FLOP distribution between attention and MLP components shifts, and many capabilities show emergent phase transitions that only appear at larger compute budgets.

-

Emergent capabilities often appear abruptly and only after crossing specific thresholds in model size or training FLOPs.

-

Small-scale experimentation can therefore produce misleading conclusions about which architectural or optimization choices matter at production scale.

- This reality demands both caution when generalizing from limited experiments and techniques for predicting large-scale outcomes from limited compute.

Practical implications and guidance:

-

Treat small-scale results as provisional. Avoid assuming behaviors observed at low scale will persist unchanged at production scale.

-

Identify scale-dependent phenomena. Map which behaviors shift with size or FLOPs so you know what requires larger-scale validation.

-

Invest in prediction or extrapolation methods. Use appropriate techniques to infer likely large-scale outcomes when full-scale runs are infeasible.

-

Allocate resources strategically. Study what can be safely explored on limited compute, and reserve extrapolation or different methodologies for behaviors that likely manifest only past thresholds.

Three types of knowledge required for language-model research

Effective language-model research combines three knowledge categories:

-

Mechanics — implementational details such as transformer internals and parallelism strategies.

- These are teachable through hands-on implementation exercises covering tokenization, model architectures, and training loops.

- These are teachable through hands-on implementation exercises covering tokenization, model architectures, and training loops.

-

Mindset — an emphasis on efficiency and scaling-aware design.

- This includes treating resource accounting and efficiency as first-class design goals.

- This includes treating resource accounting and efficiency as first-class design goals.

-

Intuitions — empirical priors about what data and modeling choices work in practice.

- These are learned partly through experience and experimentation and may not transfer perfectly across scales.

- These are learned partly through experience and experimentation and may not transfer perfectly across scales.

The course aims to deliver Mechanics and Mindset comprehensively, while providing partial, practical exposure to Intuitions.

Empirical experimentation often outweighs handwavy explanations

Architectural improvements and training heuristics are often adopted because of empirical gains rather than a complete theoretical explanation—experimental results remain the ultimate arbiter for which changes scale in practical systems.

Algorithms and activation functions that look promising are validated through controlled evaluation and ablation studies, not merely by analytic derivations or persuasive intuition.

To build reliable models you should prioritize a few core practices:

-

Reproducible experimental workflow — ensure experiments can be rerun and independently verified.

-

Controlled evaluation — isolate variables so changes can be attributed confidently.

-

Ablation studies — remove or alter components to measure their individual contributions.

-

Precise measurement — use well-defined metrics and report uncertainty or variance.

-

Skepticism about intuitive stories — prefer measured evidence over appealing but untested narratives.

A simple, pragmatic workflow to follow:

- State the hypothesis and the expected measurable effect.

- Design controlled experiments and include ablations to isolate factors.

- Run reproducible trials and record precise metrics (with confidence intervals or variance).

- Base adoption decisions on measured performance, not on persuasive rationale alone.

The ‘bitter lesson’ reframed: algorithms at scale and efficiency matter

The correct interpretation of the ‘bitter lesson’ is that algorithmic efficiency combined with scale drives progress — it is not a claim that scale alone suffices without algorithmic improvements.

Over the last decade, algorithmic gains have produced order-of-magnitude improvements in resource efficiency, often exceeding hardware-driven improvements such as Moore’s law.

Because efficiency multiplies the value of compute, it directly reduces monetary and time costs — a critical effect when training costs are measured in the millions.

Therefore, optimizing algorithms, schedules, and system utilization is an essential research objective alongside scaling.

- Benefits of prioritizing efficiency:

-

Higher leverage of compute for the same budget or faster progress for the same resources.

-

Lower monetary and time costs, making large-scale experiments more accessible and repeatable.

- Complementarity with scaling: algorithmic improvements increase the returns to additional compute rather than replacing the need to scale.

-

Higher leverage of compute for the same budget or faster progress for the same resources.

Research framing: maximize accuracy per resource and historical landscape

Frame research as optimizing model accuracy given a fixed compute and data budget—ask which model and training decisions yield the best performance per resource unit.

Historical context matters: many foundational components emerged over years and collectively enabled modern transformers and foundation models.

-

Neural LMs — early language modeling architectures that set the stage for sequence-based learning

-

Seq2seq — enabled conditional generation and structured prediction for variable-length inputs and outputs

-

Adam optimizer — improved and stabilized training across many architectures

-

Attention mechanisms — provided flexible, content-dependent weighting that transformers build on

-

Model-parallel techniques — allowed scaling beyond single-device limits and made very large models feasible

Foundation models such as ELMo, BERT, and T5 demonstrated the value of pretraining and transfer learning—showing that generic, pretrained representations can be adapted to many downstream tasks.

Later, engineering and scaling practices translated these ideas into very large autoregressive models, which dominate much of the current landscape.

Understanding both the historical ingredients and the present mix of closed and open models helps reconstruct best practices from public information and guides resource-constrained research decisions.

Executable, code-embedded lectures as a teaching artifact

An executable lecture is a pedagogical artifact that interleaves narrative exposition with live, navigable code—enabling step-through execution, inspection of environment variables, and jump-to-definition workflows.

-

Interleaves explanation and runnable code: narrative and code live side-by-side so readers can follow intent and implementation together, then execute or step through examples in-place.

-

Embeds runnable examples with hierarchical organization: structured, nested examples increase reproducibility and reduce the friction of translating conceptual descriptions into working implementations.

-

Enables deep inspection and debugging: students can inspect training components, debug with visibility into runtime state, and follow exact computational steps used to produce results.

-

Supports hands-on learning: by making code-as-lecture first-class and easily examinable, the format turns passive reading into active exploration and experimentation.

Course logistics, prerequisites, and expectations

The course provides online lectures, assignments, unit tests, and a cluster for large experiments — but it requires a substantial time commitment and a readiness to implement low-level components from scratch.

-

Assignments are scaffold-free: students receive minimal starter code and are expected to design software APIs, pass unit tests, and produce efficient implementations suitable for benchmarking.

- A partner-supplied cluster provides H100 access for performance-critical runs. Students are instructed to prototype locally on small datasets before using cluster resources.

-

Grading combines correctness (unit tests) and empirical performance metrics.

-

Accommodations such as auditing access to materials are supported.

Recommended workflow for experiments:

-

Prototype locally on small datasets to validate correctness and iterate quickly.

-

Pass unit tests and perform small-scale benchmarks locally.

- Use the partner cluster (H100) only for performance-critical runs and final benchmarking.

Course structure and the ‘efficiency-first’ design philosophy

The course is organized into five units that form a pipeline from tokenization through alignment, with an overarching emphasis on maximizing accuracy per unit of compute and data.

-

Basics — tokenization, model, training.

-

Systems — kernels and parallelism.

-

Scaling laws — hyperparameter prediction.

-

Data — curation and evaluation.

-

Alignment — instruction tuning and learning from feedback.

The pedagogical approach is bottom-up: implement primitives, measure costs, and iterate toward efficiency.

-

Implement core primitives (the essential building blocks).

-

Measure resource consumption (compute, memory, I/O).

-

Iterate on designs to improve accuracy per unit of compute and data.

Every unit emphasizes benchmarking, profiling, and principled trade-off analysis when allocating compute and data budgets.

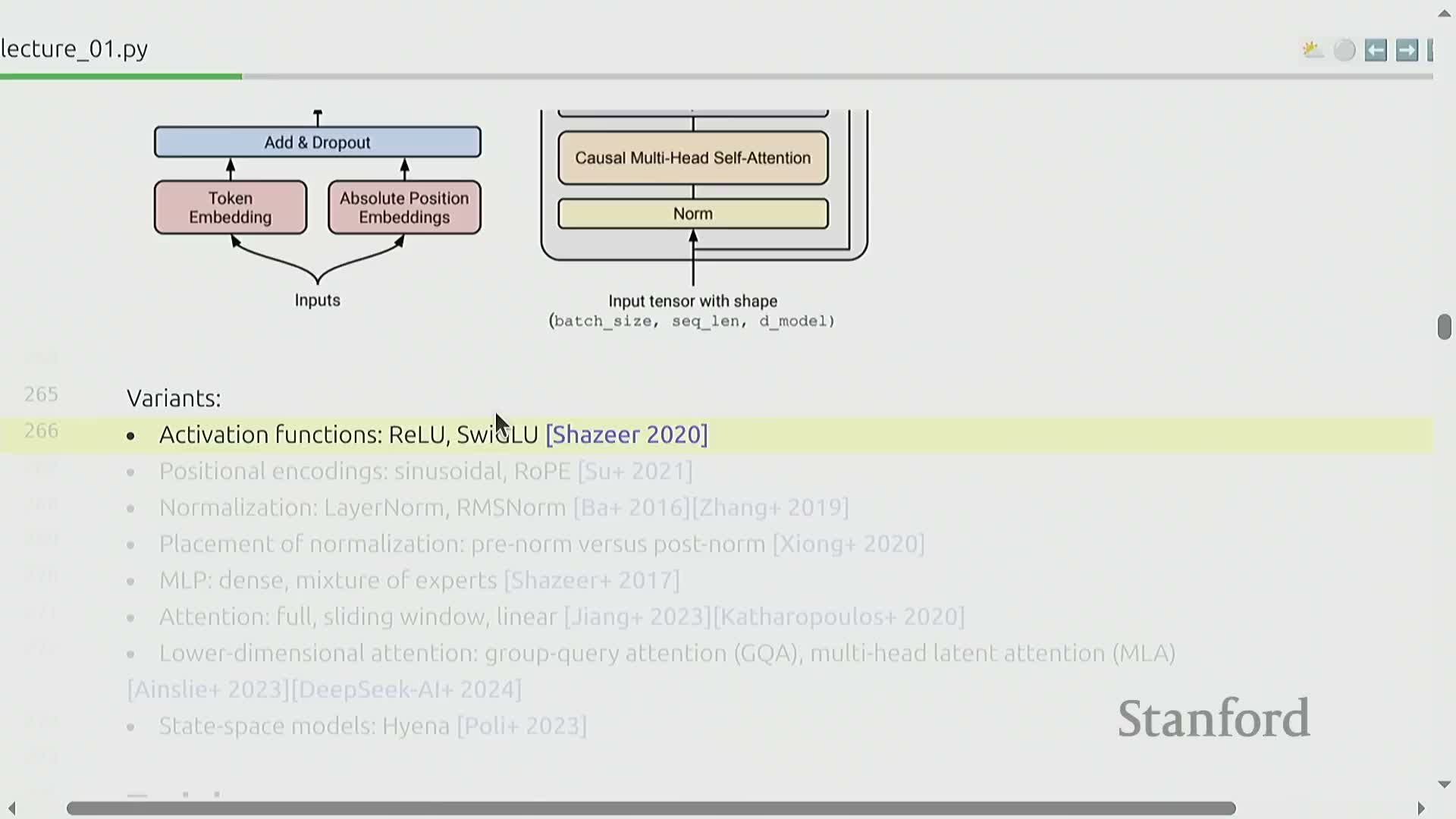

Basics unit: tokenizer, transformer architecture, and training loop

The basics unit requires implementing three core components:

-

A reversible tokenizer — a lossless mapping between strings and integer sequences (so tokens can be decoded back to text).

-

A transformer-based autoregressive model — the sequence model that predicts next-token probabilities.

-

A complete training loop — including loss computation and optimization routines.

Tokenization:

- Tokenization maps strings to integer sequences suitable for fixed-dimensional models.

- The course focuses on byte-pair encoding (BPE) as the primary algorithm.

- It also notes emerging tokenizer-free architectures that operate on raw bytes instead of discrete token vocabularies.

Model module:

- Centers on transformer building blocks: attention, MLPs, and normalization.

- Highlights modern variants and choices that affect capacity and efficiency:

-

SwiGLU activations

-

Rotary positional encodings (RoPE)

-

RMSNorm placement and alternatives

-

SwiGLU activations

Training stack (practical components and decisions):

-

Optimizer choices — e.g., AdamW, and their hyperparameter settings.

-

Learning-rate scheduling — warmups, decays, and schedule shape.

-

Batch sizing — effective batch size, micro-batching, and memory trade-offs.

-

Regularization — weight decay, dropout, and other techniques.

Small engineering choices in the training stack — from optimizer hyperparameters to batching strategy — materially affect final performance and efficiency.

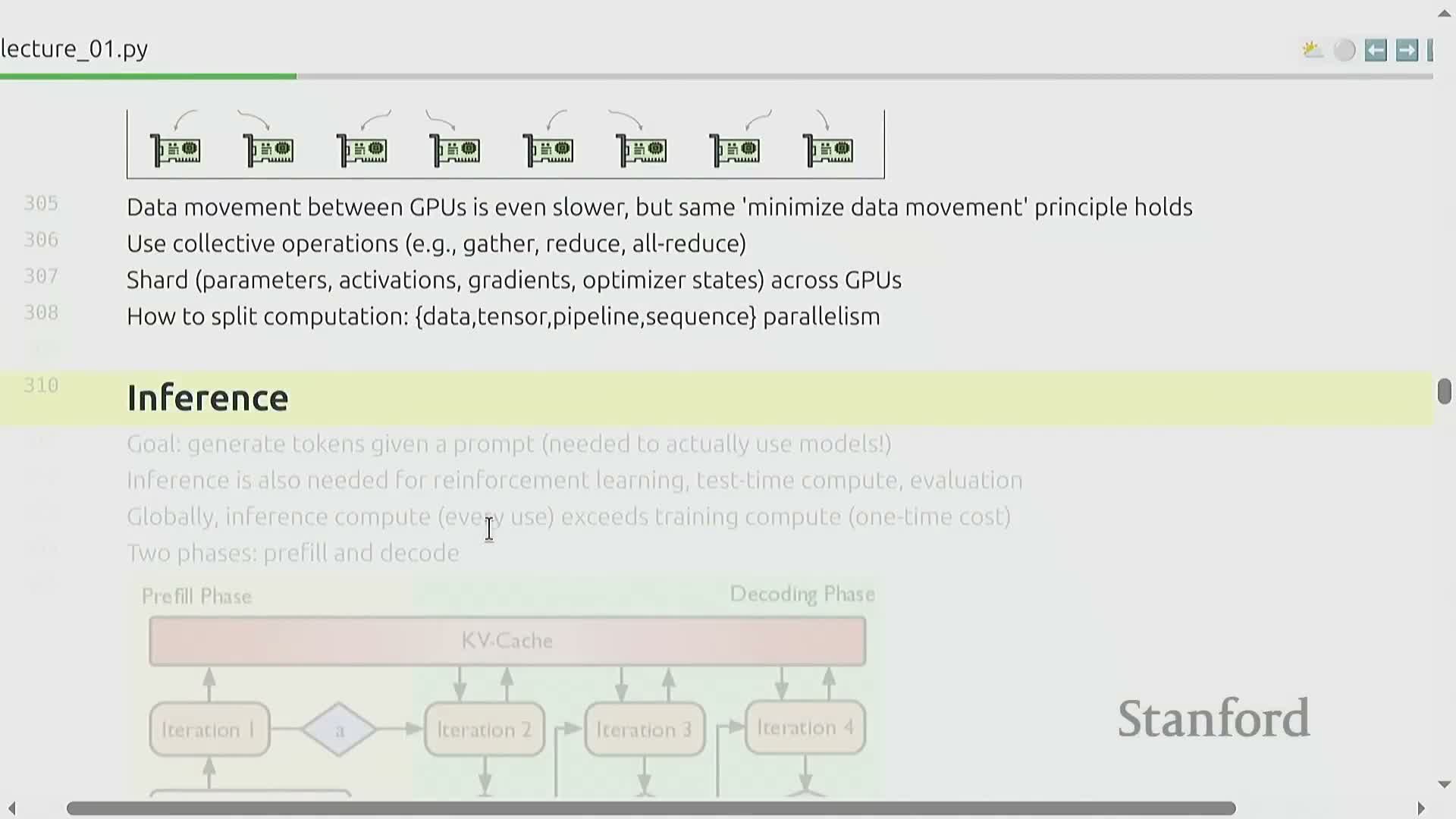

Systems unit: kernels, multi-GPU parallelism, and inference optimization

Systems content centers on maximizing GPU utilization by minimizing data movement and optimizing kernels.

Focus spans both single-GPU kernel techniques (e.g., fusion, tiling) and multi-GPU partitioning strategies.

-

Single-GPU kernel optimizations

-

Fusion: combine multiple operations into one kernel to reduce memory traffic

-

Tiling: arrange computation to improve data locality and reuse

-

Fusion: combine multiple operations into one kernel to reduce memory traffic

-

Multi-GPU partitioning

- Strategically place compute and state across devices to balance bandwidth, latency, and memory constraints

- Strategically place compute and state across devices to balance bandwidth, latency, and memory constraints

GPU architecture imposes a memory–vs–compute trade-off: on-chip compute must be continuously fed from off-chip memory and inter-GPU links, so arranging parameters, activations, and communication paths is critical.

Practical tooling such as Triton is used for writing high-performance custom kernels that target these bottlenecks.

Distributed-placement strategies taught include:

-

Data parallelism — replicate model state and shard the batch across devices

-

Tensor / model parallelism — split tensors or layers across GPUs to scale large models

-

Simplified FSDP variants — shard parameter and optimizer state across devices to reduce per-device memory and place state flexibly

Inference optimization covers the distinct phases of generation:

-

Pre-fill phase — initial processing to prepare model state for decoding

-

Autoregressive decode phase — token-by-token generation that often exposes memory-bound bottlenecks

- Common bottleneck: memory-bound decoding, where data movement limits throughput more than raw compute

- Advanced technique: speculative decoding — use a cheaper model to propose sequences, then verify those proposals in parallel with the full model to accelerate overall decode throughput

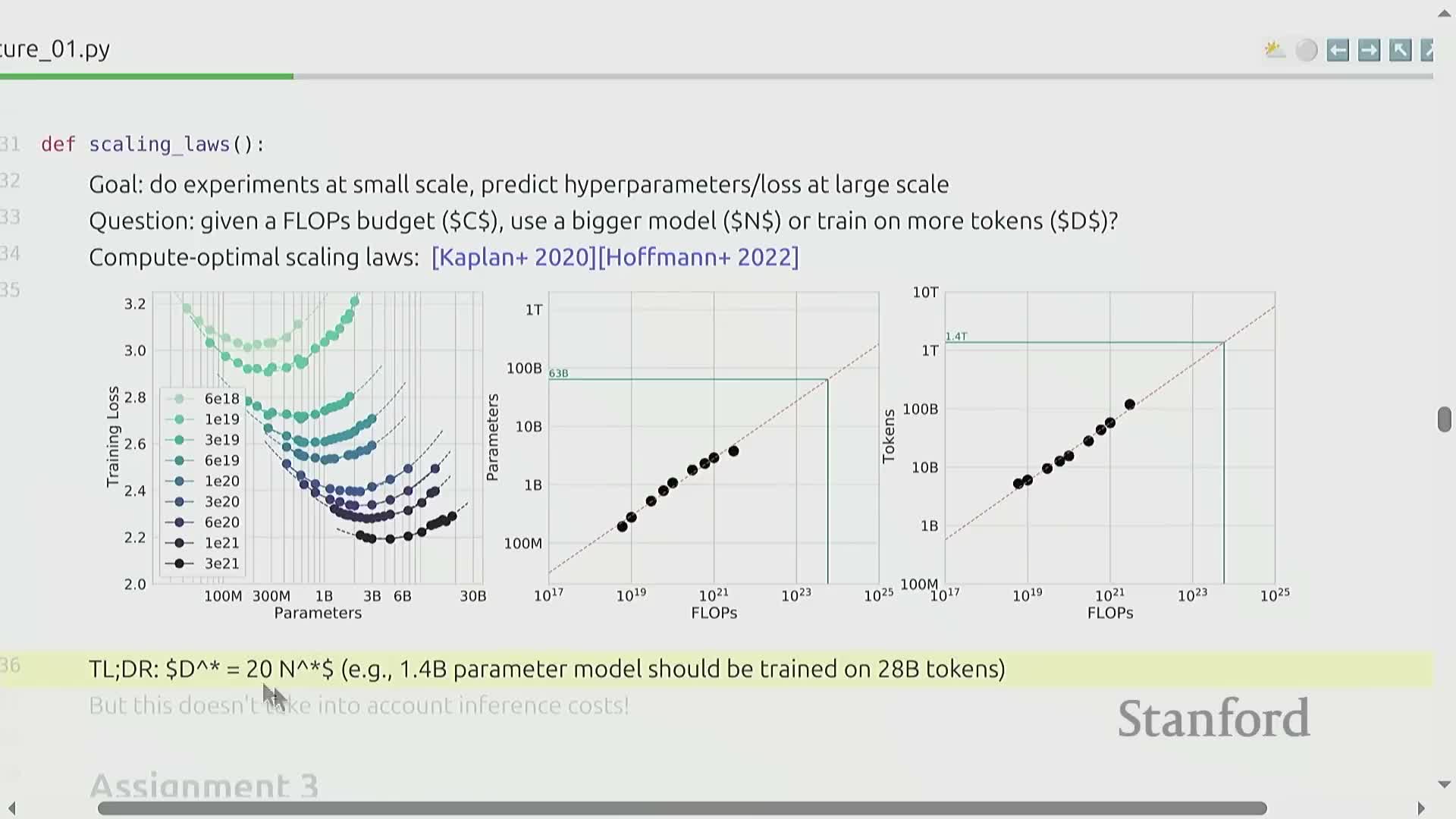

Scaling laws unit: choosing model size and training allocations under a FLOPs budget

Scaling laws study how model parameter count, dataset size, and FLOPs allocation jointly determine final performance, enabling prediction of optimal hyperparameters for a given compute budget.

Empirical scaling relationships (e.g., Chinchilla-like rules) show an approximately linear relationship between model size and training tokens.

- These give practical rules of thumb, such as a tokens-to-parameters ratio, for planning training runs.

Recommended workflow for using scaling laws to design models and experiments:

- Run small-scale experiments across a range of hyperparameters to collect loss-versus-resource data.

- Fit extrapolative curves (scaling fits) to those empirical points to capture how loss scales with model size, tokens, and FLOPs.

- Use the fitted curves to predict performance at larger scales and to select model architectures that minimize loss under a fixed FLOPs budget.

- Allocate actual compute according to those predictions, iterating as needed to reduce predictive error.

Class exercise structure (constrained, hands-on):

- Students receive a limited training API that returns loss for chosen hyperparameters.

- They have a finite FLOPs budget to spend on experiments.

- The task is to prioritize runs, fit scaling curves from few data points, and choose hyperparameters that minimize expected loss while minimizing predictive error.

Data unit: evaluation, curation, and preprocessing of web-scale sources

Data curation is treated as a primary determinant of model capabilities because the composition of training corpora determines domain abilities such as multilingualism or coding competency.

Raw web sources require substantial processing:

-

HTML and PDF need extraction and normalization.

-

Spam and boilerplate must be filtered using learned classifiers.

-

Deduplication is necessary to avoid redundant examples that can bias training.

Evaluation protocols are introduced:

-

Perplexity on held-out corpora — a primary metric for model fit.

-

Standardized benchmarks (e.g., MMLU) — for comparing domain and reasoning performance.

-

System-level evaluation for instruction-following architectures — assessing end-to-end behavior beyond token-level metrics.

Key data-acquisition decisions are discussed:

- Whether to buy curated data or rely on public crawls (trade-offs in quality, cost, and coverage).

The assignment uses raw Common Crawl to practice the full curation pipeline. Suggested workflow (numbered):

-

Extraction — parse HTML/PDF and normalize text.

-

Classifier-based filtering — remove spam, boilerplate, and low-quality pages.

-

Deduplication — eliminate repeated content to prevent training bias.

-

Empirical measurement — evaluate downstream perplexity under given token budgets to quantify the impact of curation choices.

Alignment unit: supervised fine-tuning and learning from feedback

Alignment is the process of adapting a base next-token model into an instruction-following, safe, and stylistically controllable assistant—typically achieved via supervised fine-tuning (SFT) and algorithms that learn from preference or verifier signals.

Supervised fine-tuning (SFT)

- Uses prompt–response pairs to teach instruction-following behavior.

- Often a small, curated dataset is sufficient to yield large gains when starting from a capable base model.

Learning-from-feedback techniques

- Expand supervision efficiency by leveraging preference labels (A/B comparisons) or verifiers that score outputs.

- These signals enable optimization algorithms to train models directly from human or automated judgments.

- Common algorithmic choices include:

- PPO (policy gradient–based reinforcement learning)

- More recent, simplified approaches such as DPO (direct preference optimization) that avoid full RL complexity

Typical workflow for learning-from-feedback (high level):

- Generate model outputs for a set of prompts.

- Collect preference annotations (A/B) or verifier scores for those outputs.

- Apply an optimization algorithm (e.g., PPO, DPO) to update the model from those signals.

Policy optimization variants and trade-offs

- Methods like group relative preference optimization (GRPO) reduce complexity compared to full RL pipelines while still leveraging preference information.

- Practical trade-offs to consider:

- Annotation cost — collecting high-quality preference labels or verifier data can be expensive.

- Algorithmic stability — more complex RL-style pipelines can be less stable and harder to tune than simpler direct optimization methods.

Efficiency-first recap and regime-dependent design choices

Design decisions across tokenization, architecture, data processing, and training are driven by the compute-and-data regime.

When compute is scarce, teams prioritize:

-

Aggressive filtering to reduce training workload

-

Tokenization compression to lower sequence length and model cost

-

Architecture choices that reduce training cost, even if they trade off some raw accuracy

The unifying metric is efficiency: accuracy per resource rather than raw accuracy alone determines engineering and modeling choices.

As resource regimes shift (for example, from compute-constrained to data-constrained), optimal strategies may change, including:

- Adjusting epoch counts to balance reuse versus freshness of data

- Increasing data reuse or augmentation when data is scarce

- Adopting entirely different architectures better suited to the available resources

This framing guides:

- Which experiments to run

- How to prioritize development effort

- When to prefer alignment or fine-tuning over training increasingly larger base models

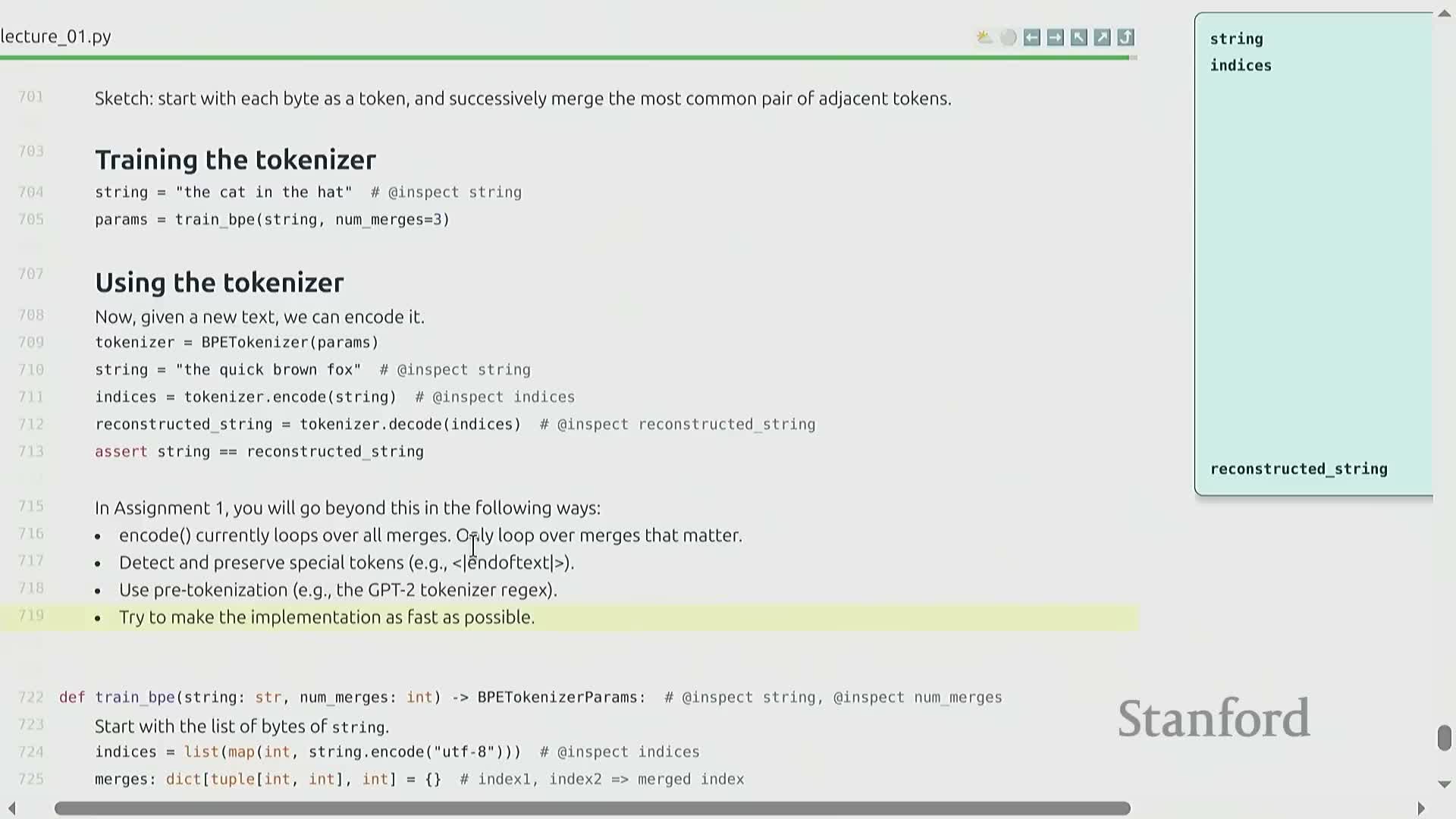

Tokenization overview and practical tokenizer behaviors

Tokenization is the reversible mapping from Unicode text to integer sequences used by models that require fixed-dimensional inputs—design choices affect compression, sequence length, and downstream efficiency.

Design choices affect:

-

Compression (how much text is packed into each token)

-

Sequence length (how many tokens a given text becomes)

-

Downstream efficiency (compute and memory costs for models)

Practical tokenizers often include pre-tokenization rules that treat leading spaces as part of tokens, making tokens context-dependent and preserving round-trip reversibility (so the original text can be recovered exactly).

Off-the-shelf tokenizers produce metrics such as bytes-per-token (compression ratio), which quantify how much natural text is compressed into model tokens.

Typical learned tokenizers achieve multiple bytes per token, improving computational efficiency relative to byte-level encodings.

Understanding how token boundaries, whitespace handling, and encoding choices affect sequence length is critical for modeling efficiency—attention costs scale superlinearly with sequence length.

Primitive tokenization schemes and their trade-offs

Primitive approaches to tokenization—character-based, byte-based, and word-based—each trade off vocabulary size, compression, and sequence length.

-

Character-based tokenization: yields small per-token semantics, and can allocate an unnecessarily large vocabulary for rare characters; this reduces modeling efficiency and compressibility.

-

Byte-based tokenization: guarantees a small fixed vocabulary (0–255) and universal reversibility, but produces long sequences, which increase attention cost in transformer architectures.

-

Word-based tokenization: adaptively reduces sequence length, yet creates an open or extremely large vocabulary, introduces unknown tokens for rare words, and complicates perplexity computation.

These limitations motivate intermediate adaptive methods such as BPE.

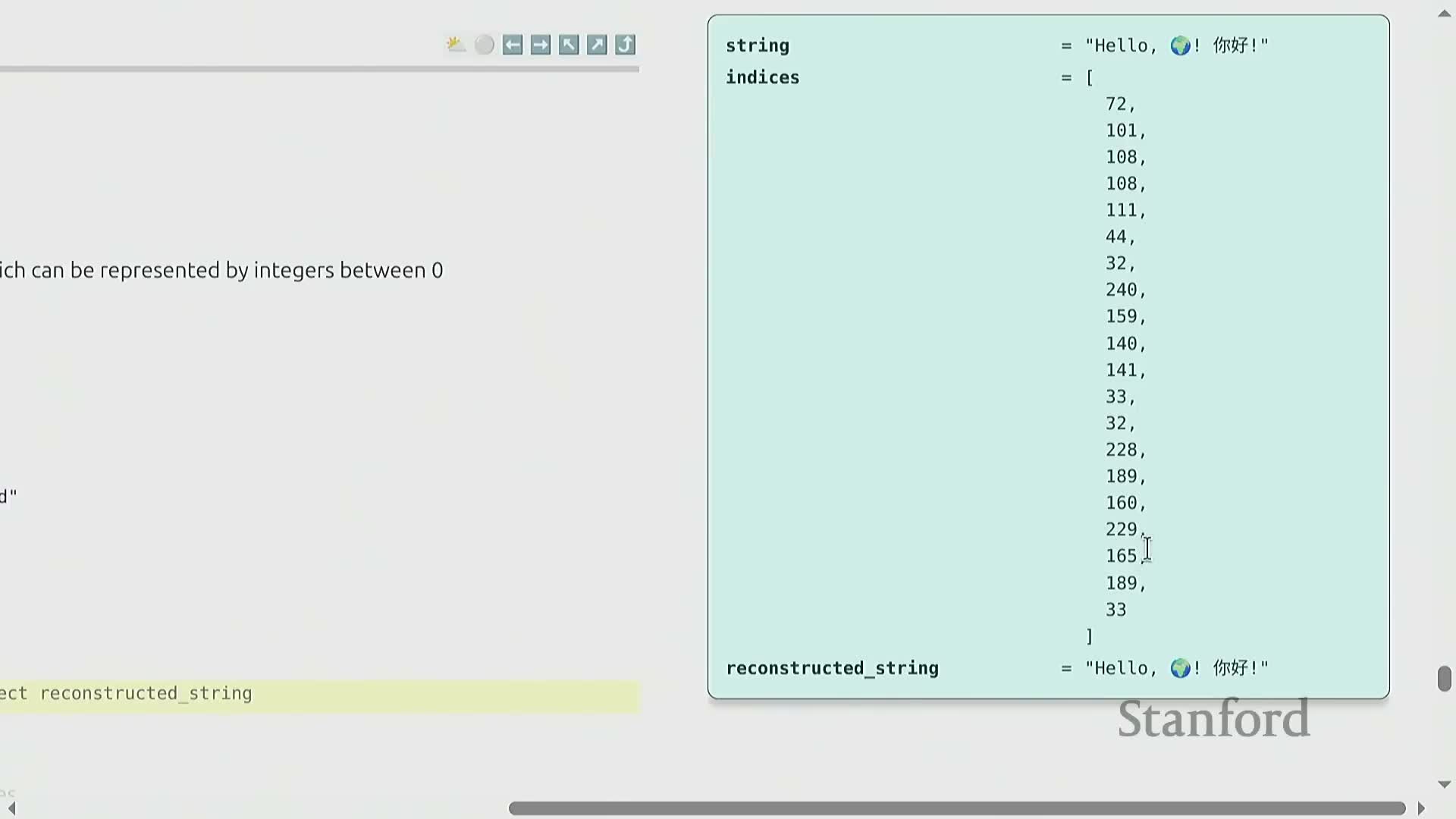

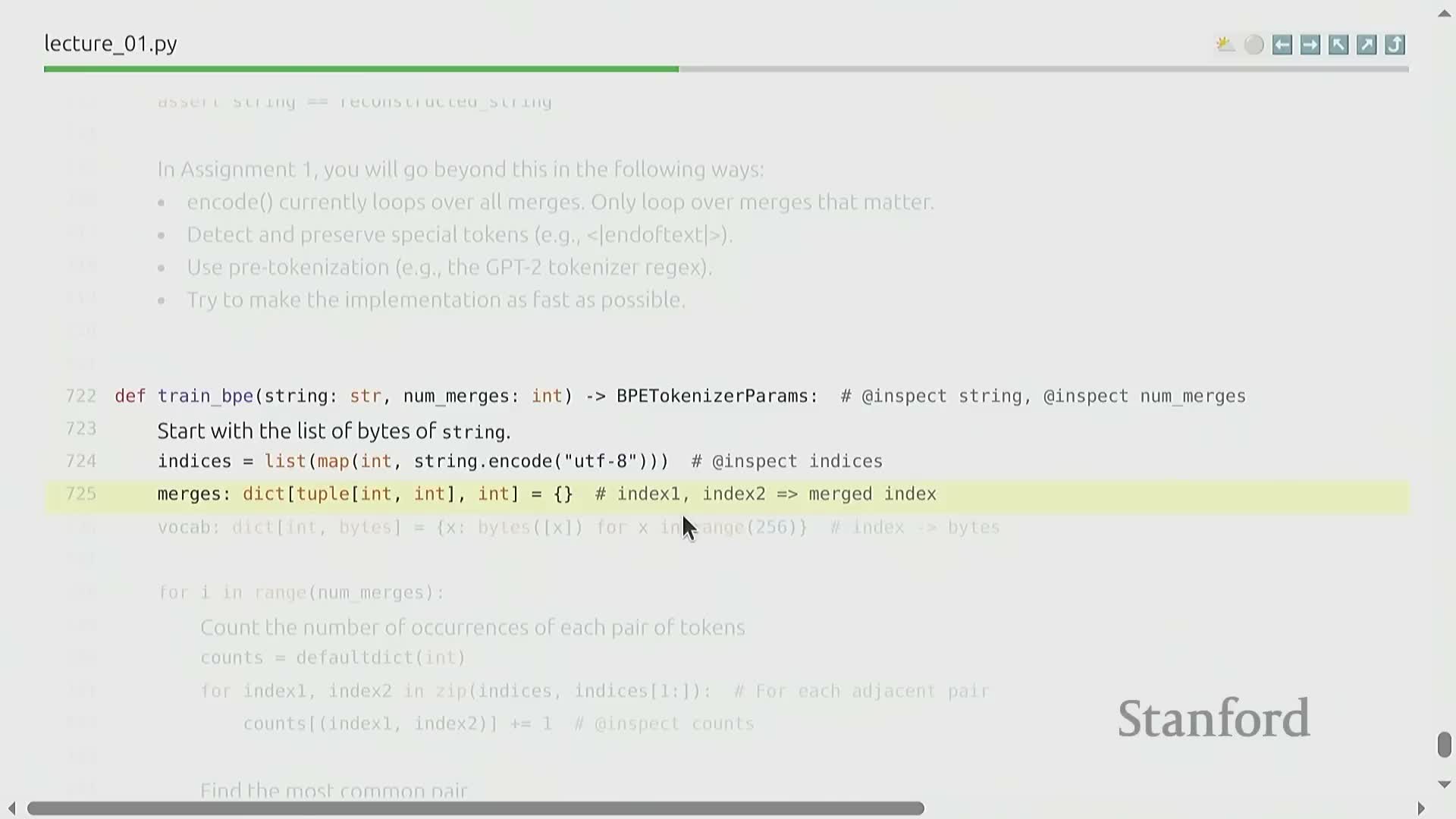

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE): algorithm and training procedure

Byte Pair Encoding (BPE) is a corpus-driven algorithm that iteratively merges the most frequent adjacent token pairs to build a compact vocabulary and improve compression — it adapts vocabulary allocation to corpus statistics.

How the algorithm works:

- Start from byte-level tokens (or pre-tokenized word segments).

- Count frequencies of adjacent token pairs across the corpus.

- Create a new merged token for the most frequent pair and replace occurrences.

- Repeat steps 2–3 for a fixed number of merges, producing a deterministic merge table and final vocabulary.

Reversibility and determinism:

- BPE records the sequence of merges in a deterministic merge table.

- Encoding and decoding replay those merges, giving a reversible mapping between text and token sequences.

Why BPE is practical (intuitive trade-offs):

- It compresses common substrings into single tokens, capturing word-like or frequent multi-character patterns.

- It represents rare strings as sequences of smaller tokens, avoiding unbounded vocabulary size.

- This balances sequence-length efficiency (shorter token sequences for common items) with a bounded vocabulary, optimizing attention cost versus vocabulary budget.

BPE implementation considerations and tokenizer deployment

A naive BPE implementation that replays merges sequentially is simple but inefficient.

Practical implementations avoid iterating over all merges for each encode. Instead, they use optimized data structures and algorithms to restrict work to the merges that actually affect the input.

Key implementation components and considerations:

-

Pre-tokenization rules — rules that split raw text into initial units before merges are applied, reducing unnecessary work and ambiguity.

-

Special token handling — explicit treatment for tokens like padding, unknowns, and task-specific markers so they remain stable across processing.

-

Efficient merge application — algorithms and indices that apply only relevant merges rather than replaying the full merge list for every input.

-

Parallelization strategies — approaches to scale tokenization across large corpora and very large vocabularies to keep throughput high.

Production tokenizers also address operational concerns:

-

Compression metrics — tracking how well the tokenizer reduces sequence length and the trade-offs involved.

-

Deterministic round-trips — ensuring encode→decode yields the original text when required, for reproducibility and debugging.

-

Performance tuning — optimizations so tokenization does not become a training-time bottleneck (memory use, I/O, batching, etc.).

Until tokenizer-free architectures scale efficiently, BPE-style tokenization remains an important engineering optimization for reducing sequence length and lowering overall training cost.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: