CS336 Lecture 4 - Mixture of experts

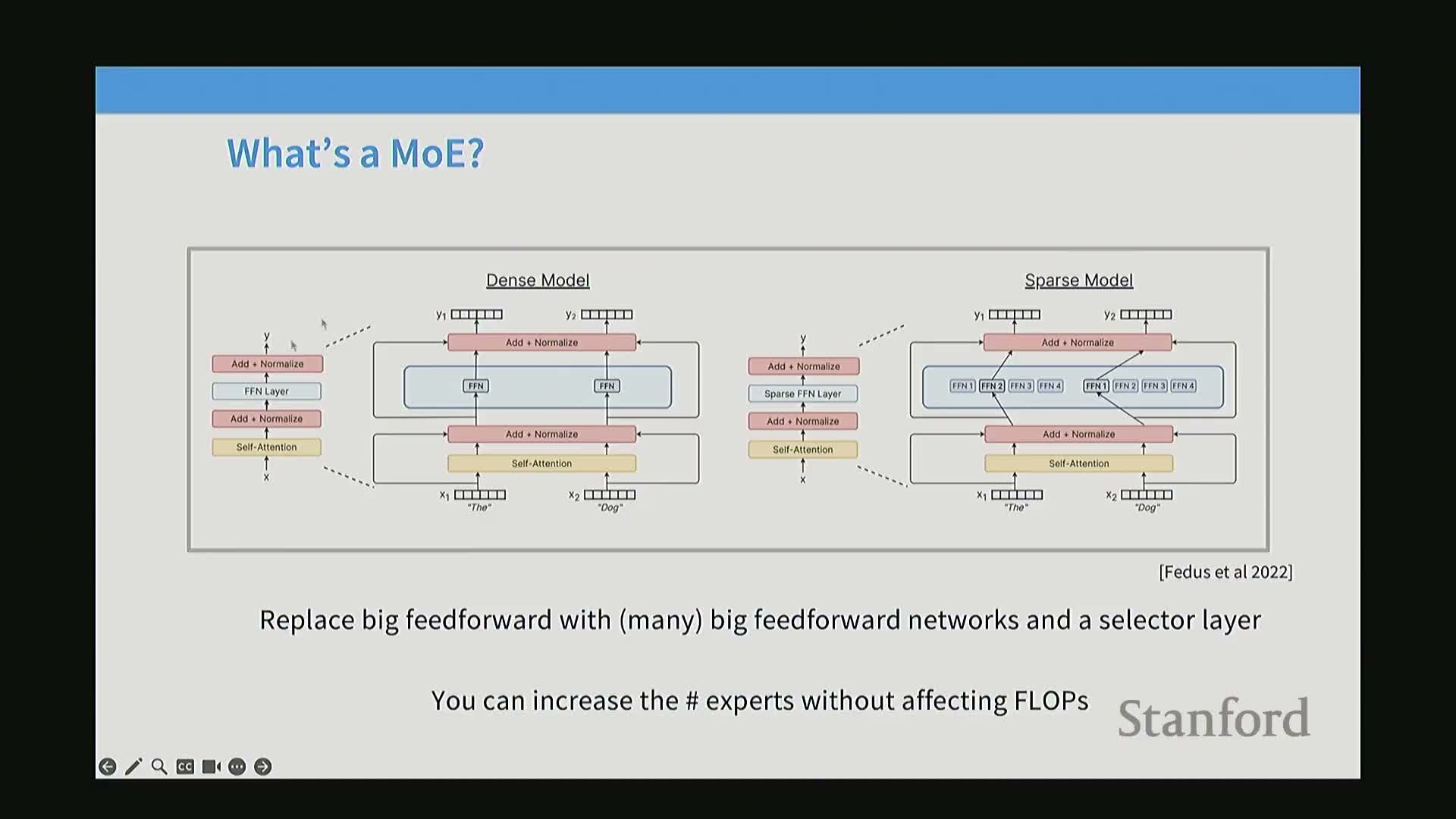

- Mixture of experts (MoE) architectures are a widely adopted sparse-activation approach for scaling model capacity without proportionally increasing FLOPs

- MoE substitutes a single feed-forward network with multiple smaller experts and a selector to obtain more parameters per FLOP

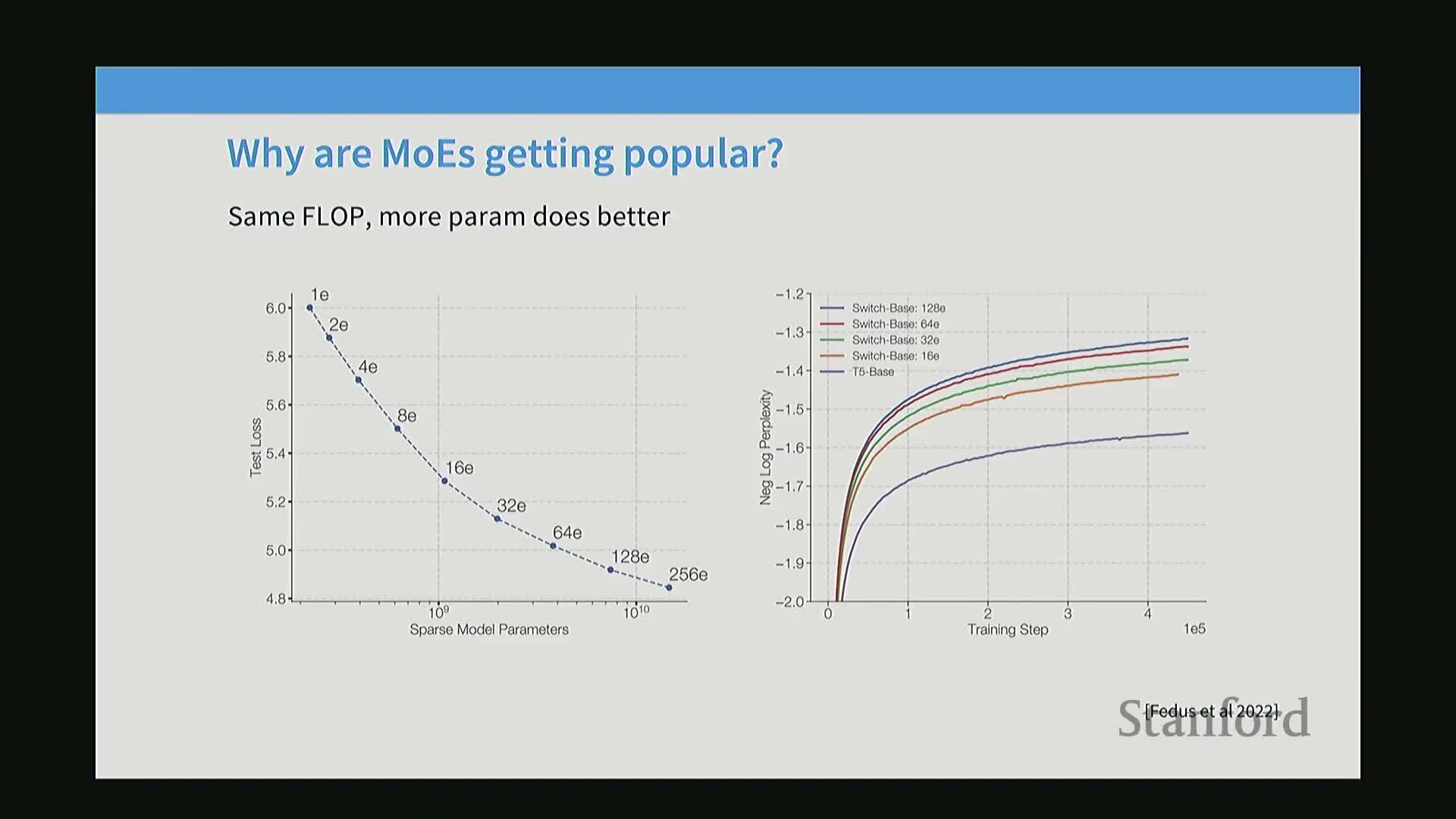

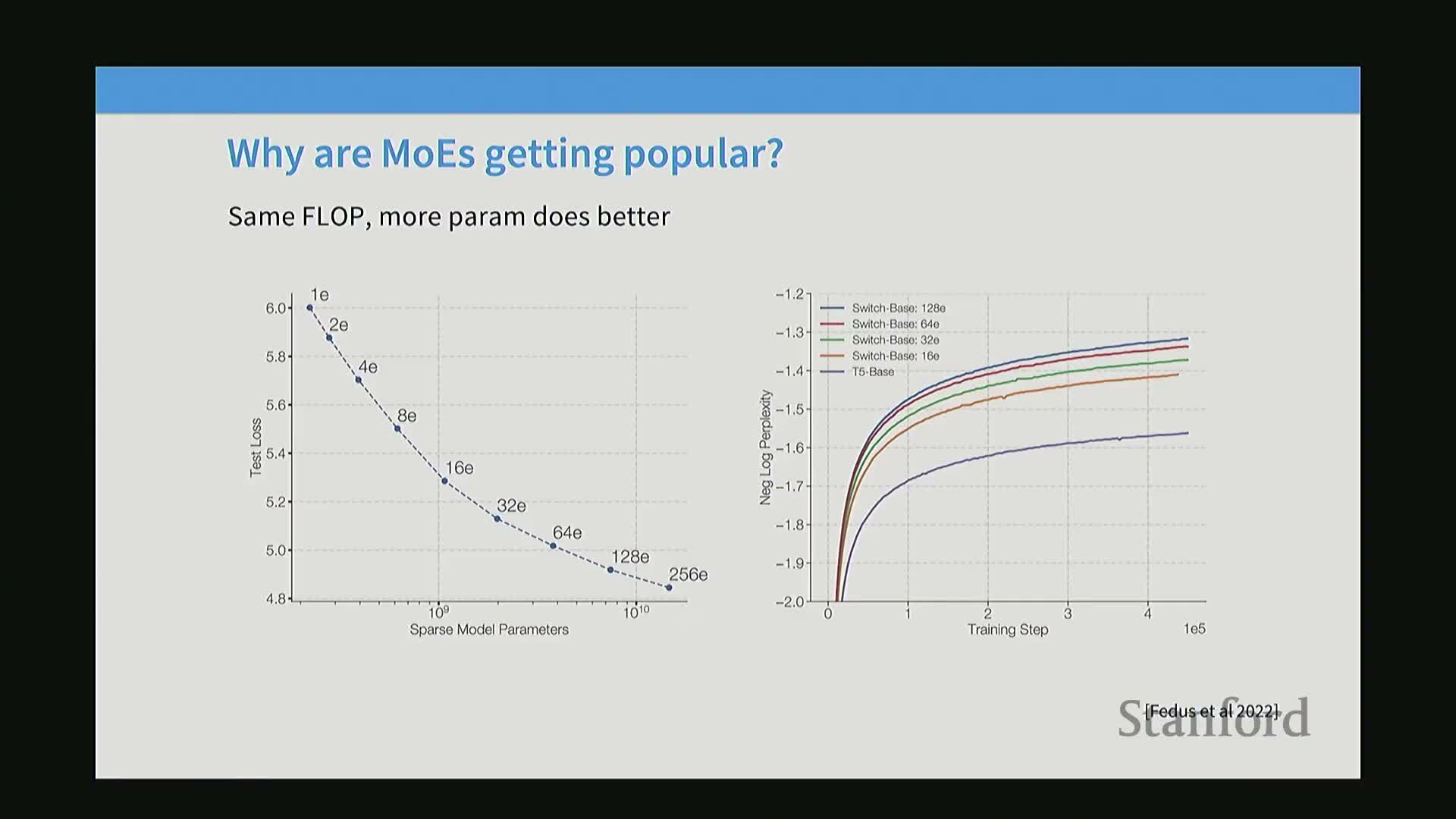

- Empirical results show that increasing the number of experts reduces training loss at matched FLOP budgets

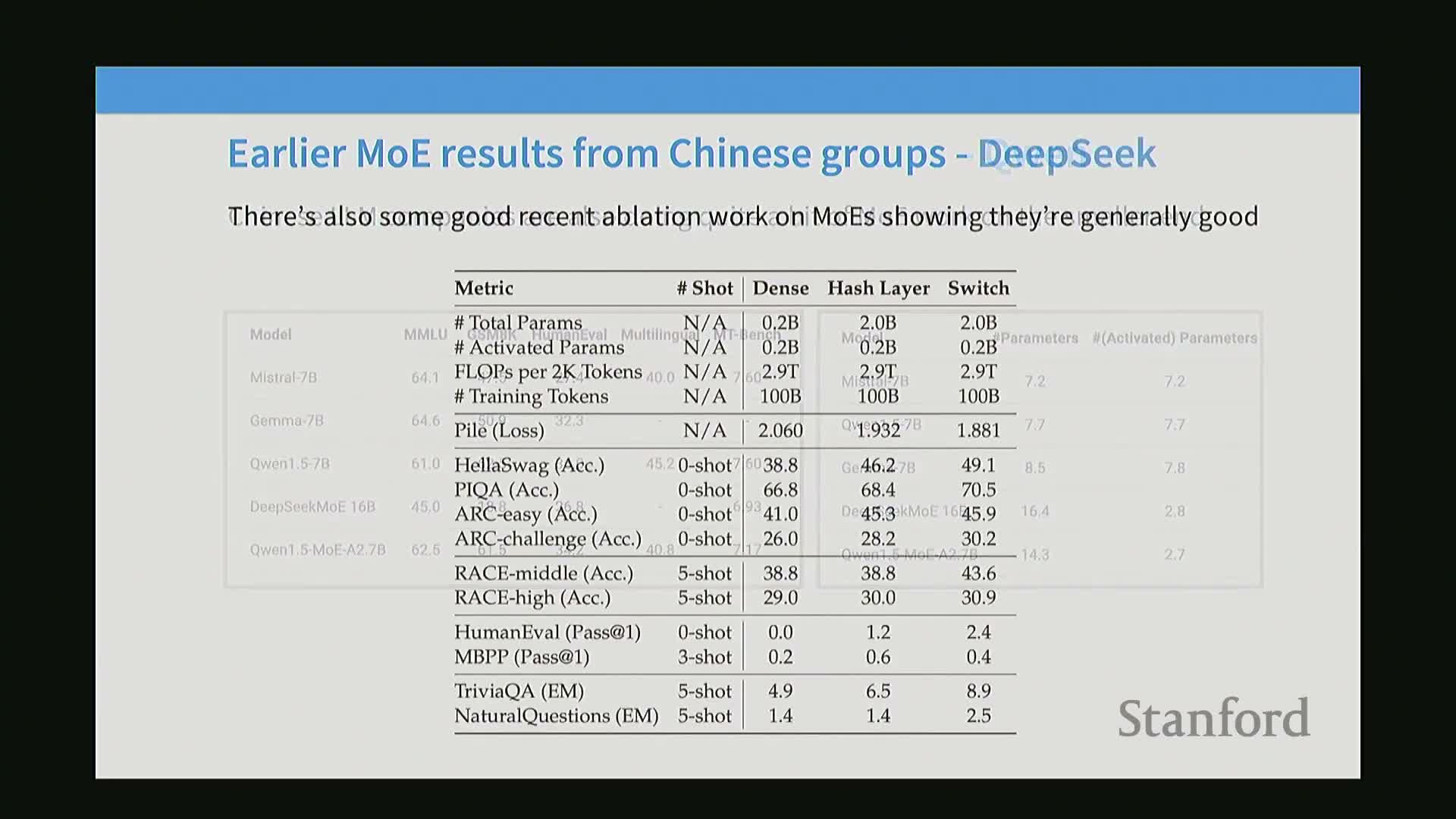

- Multiple independent replications and ablation studies corroborate MoE advantages over dense models across architectures

- Activated-parameter metrics and system-level considerations change how MoE performance is reported and perceived

- Expert parallelism gives MoE a natural and scalable axis of model parallelism across devices

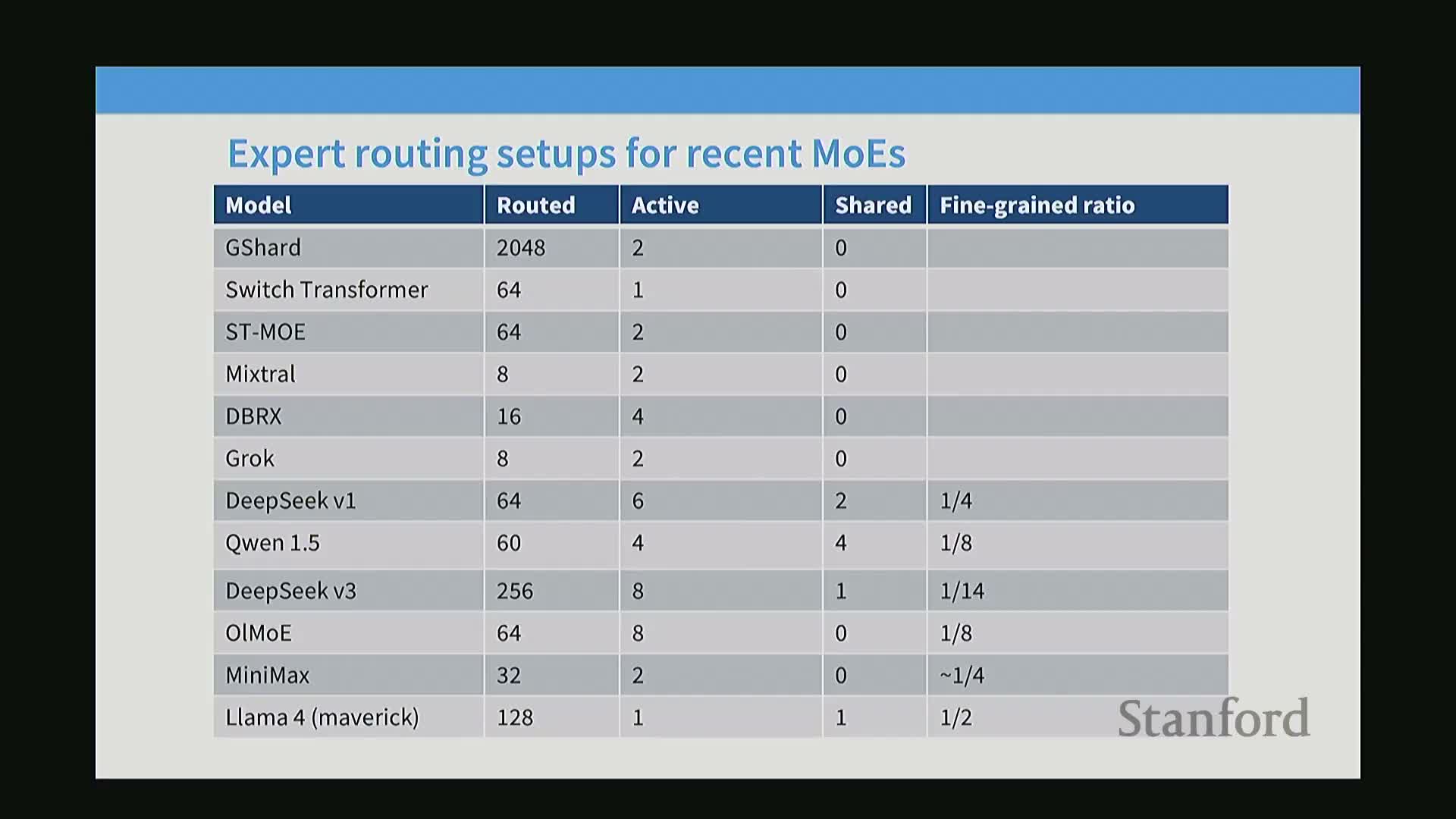

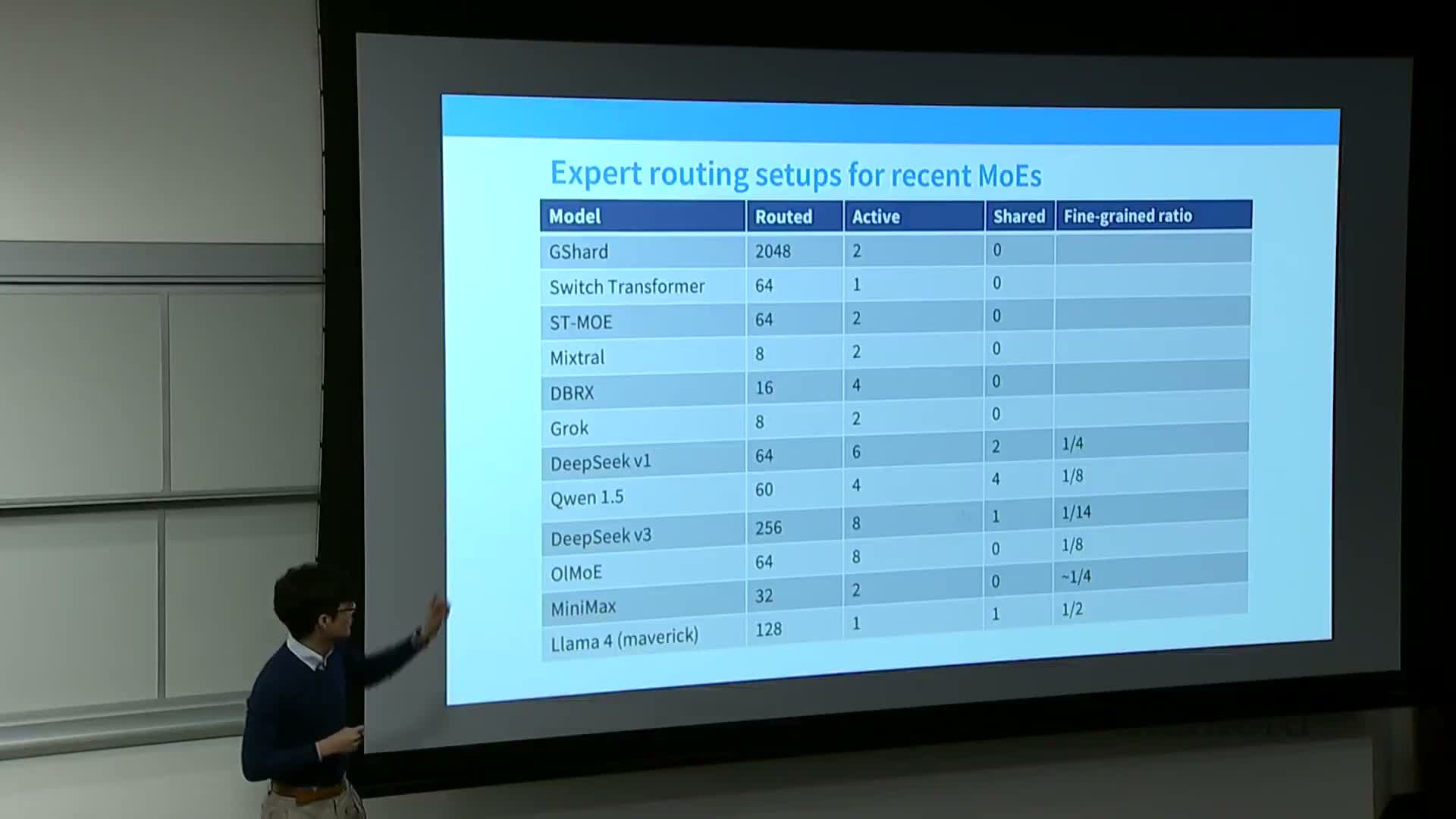

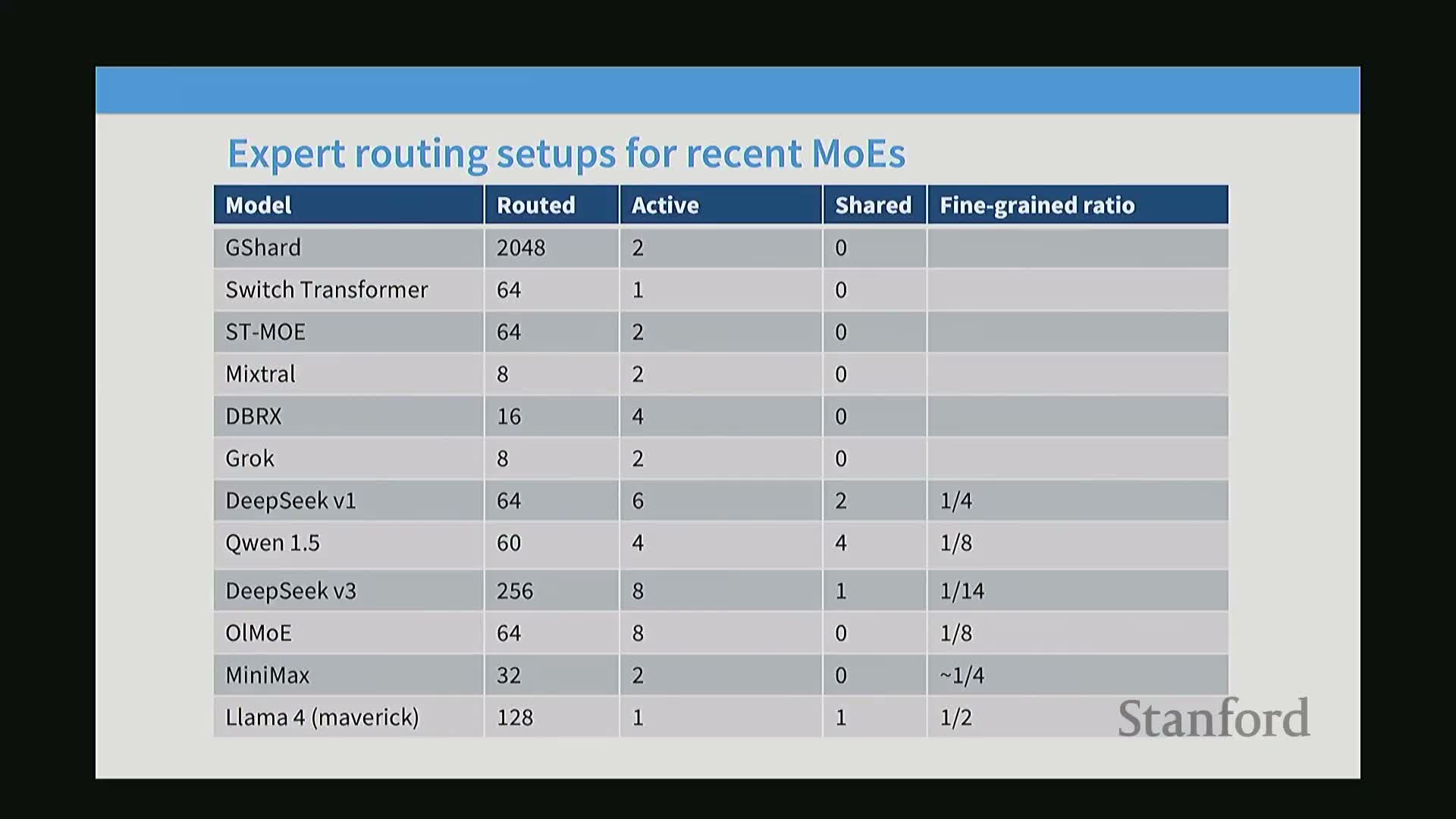

- Early open-source and industry efforts (Quen, DeepSeek, Grok, Llama 4) operationalized MoE and introduced practical engineering patterns

- MoE adoption is limited by systems complexity and the discrete non-differentiable routing optimization problem

- Routing design options include token-choice top-k, expert-choice top-k, and global assignment, with token-choice top-k predominating in practice

- Routers are typically lightweight linear scoring functions on the token hidden state and top-k gating combines selected expert outputs

- Non-semantic hashing and simple routing variants can produce empirical gains, indicating that some sparsity benefits derive from capacity partitioning rather than learned semantic routing

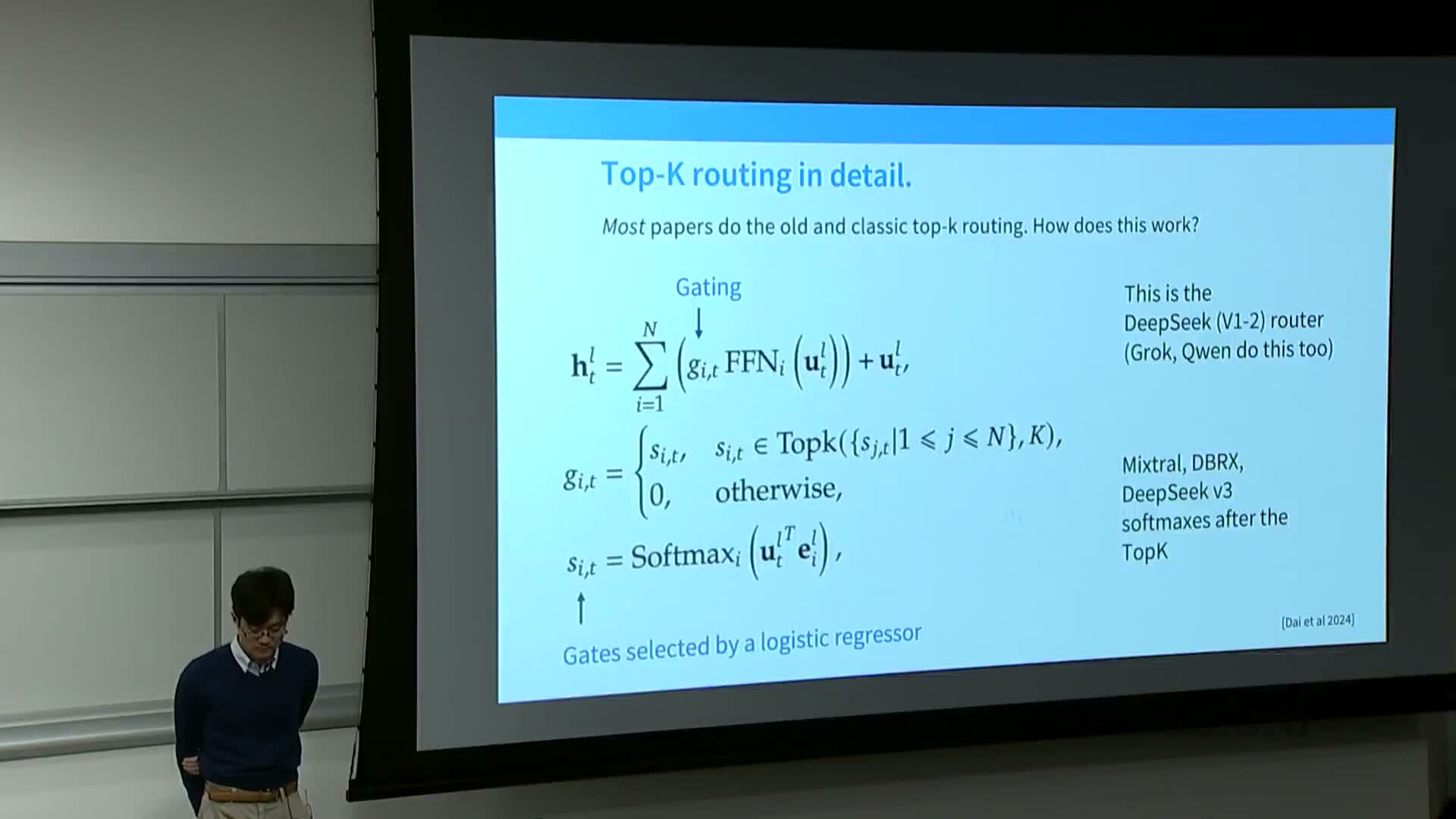

- Top-k token-choice routing computes expert affinities via learned expert vectors and softmaxed scores followed by a top-k selection and gated aggregation

- Softmax normalization and top-k interact subtly; normalization preserves weighted averages while top-k enforces sparsity for systems efficiency

- Router complexity is intentionally kept low because routing computation itself must be cheap and learning signals for routing are weak

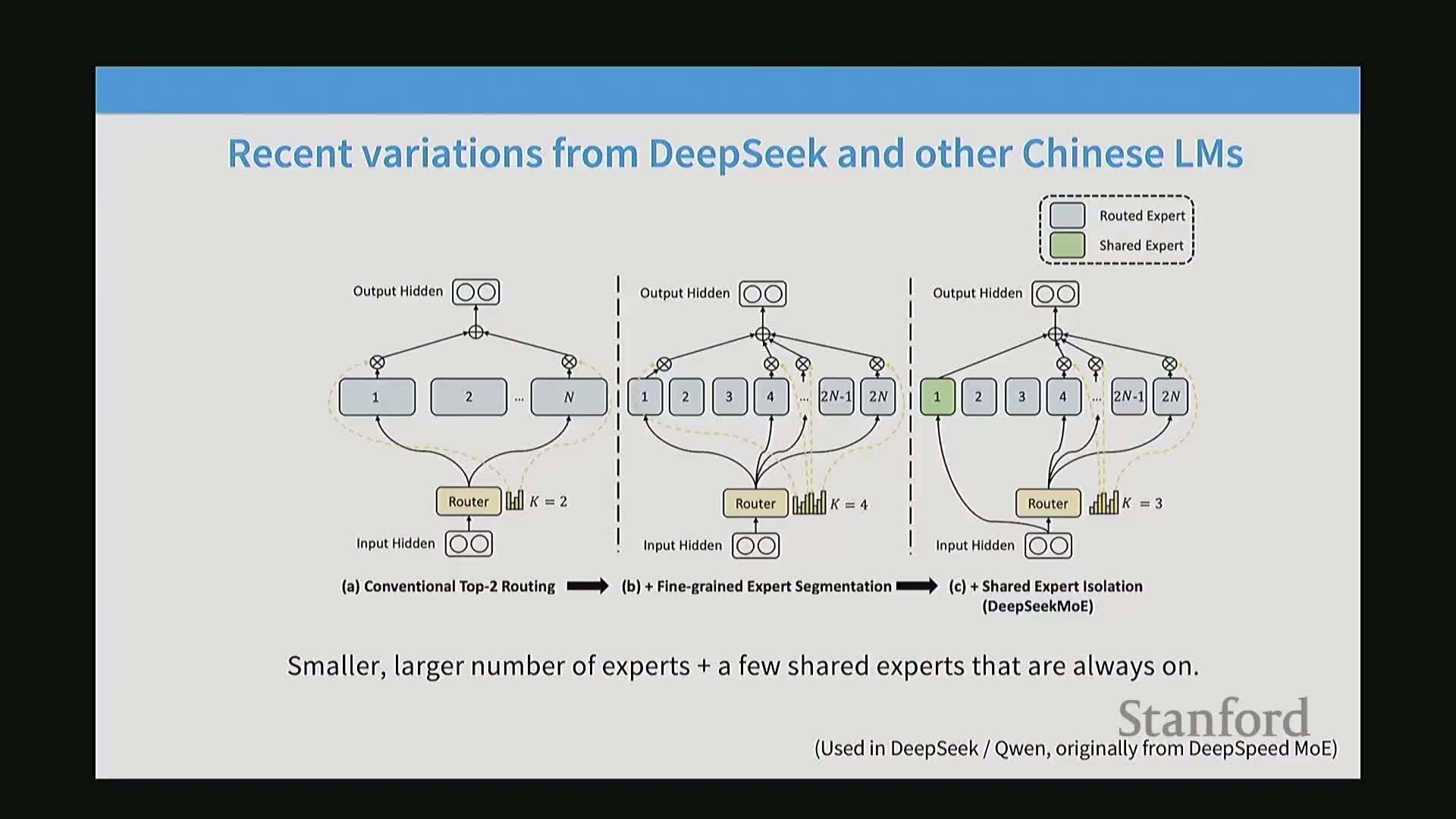

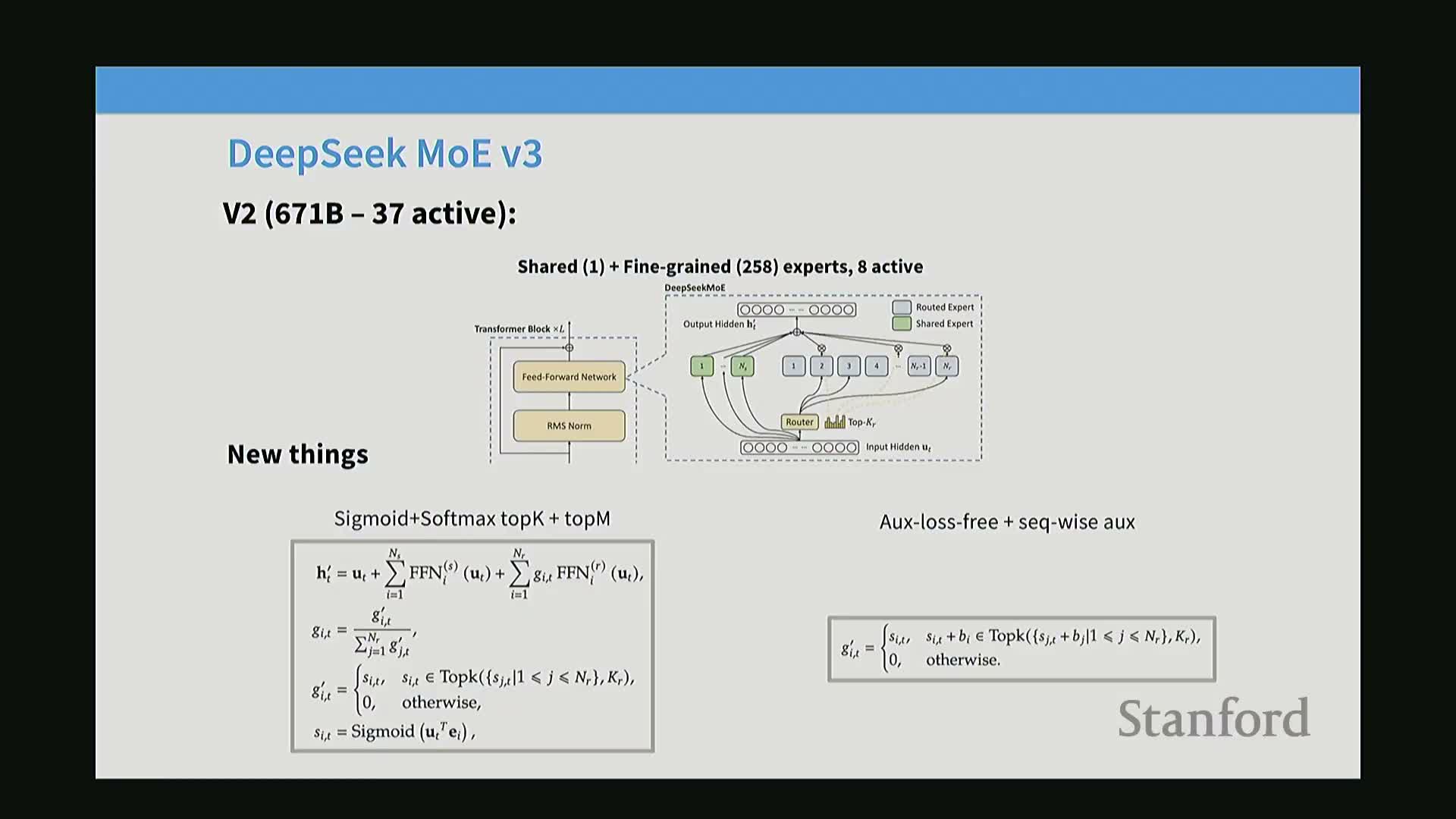

- Fine-grained experts and shared experts enable many more total experts without proportional parameter cost increases

- Common MoE configurations use many fine-grained experts with small per-expert slices and a small number of activated experts per token

- Recap of the MoE forward pass highlights routing, expert selection, gated aggregation, and the residual connection

- Training MoE is challenging due to non-differentiable sparse decisions, and three practical approaches are RL, stochastic approximation, and balancing heuristics

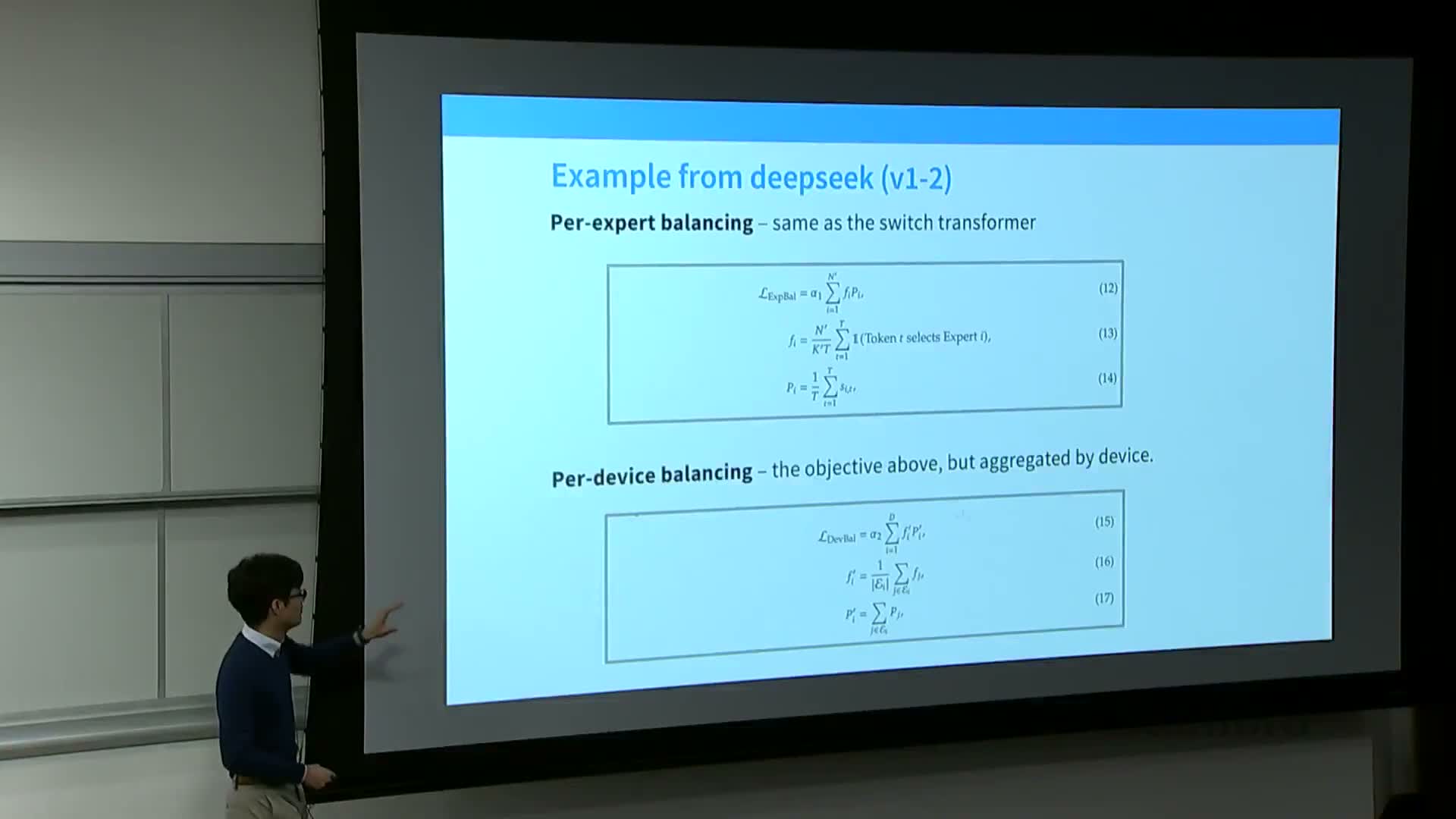

- Balancing losses (f · p) are the practical standard to prevent expert collapse and ensure even utilization across batches and devices

- Auxiliary loss-free balancing (per-expert offsets b_i) is an alternative learned online offset scheme used in modern MoE implementations

- Per-expert balancing is necessary even without systems constraints because routers otherwise deaden many experts and effectively reduce model capacity

- Expert placement and communication create batching-dependent stochasticity and token dropping that can affect determinism and outputs

- MoE models exhibit training instability and fine-tuning fragility that require numerical and architectural stabilization techniques

- DeepSeek v1→v2→v3 exemplifies MoE evolution: consistent core topology with iterative systems and routing refinements such as top-m device selection, communication balancing, KV compression, and multi-token prediction

Mixture of experts (MoE) architectures are a widely adopted sparse-activation approach for scaling model capacity without proportionally increasing FLOPs

Mixture of Experts (MoE) architectures replace dense feed-forward blocks with multiple specialized subcomponents called experts and a router that activates only a subset of experts per token or input.

-

Sparse activation lets the model store far more parameters while keeping per-step floating-point operations (FLOPs) similar to a dense model. This increases capacity for memorization and representational richness under a fixed FLOP budget.

- MoE is most commonly applied to transformer feed-forward (MLP) layers: the FFN is split or copied into many smaller expert MLPs, and a router selects the active subset for each token.

- Large-scale adoption across labs shows practical gains in training loss and downstream metrics when MoE is carefully designed and implemented.

- The technique trades memory and systems complexity for parameter efficiency and better compute-per-parameter scaling.

MoE substitutes a single feed-forward network with multiple smaller experts and a selector to obtain more parameters per FLOP

MoE design summary: replace the single dense FFN in a transformer block with a router and many smaller expert MLPs, where the router activates only a few experts per token.

- When an individual expert matches the original FFN computation but only one expert is activated, per-step FLOPs stay equivalent to the dense model while total parameter count increases—raising the parameter-to-FLOP ratio.

- This enables larger effective model capacity without increasing per-step compute, benefiting tasks that exploit extra parameters (e.g., factual memorization).

- Key implementation choices:

-

Copying vs splitting FFN weights into experts (naive copy vs fine-grained slicing).

- Designing the selector (router) to operate on hidden states (not raw tokens).

-

Copying vs splitting FFN weights into experts (naive copy vs fine-grained slicing).

- Payoffs come with engineering and memory costs that require careful systems-level planning for multi-device training and inference.

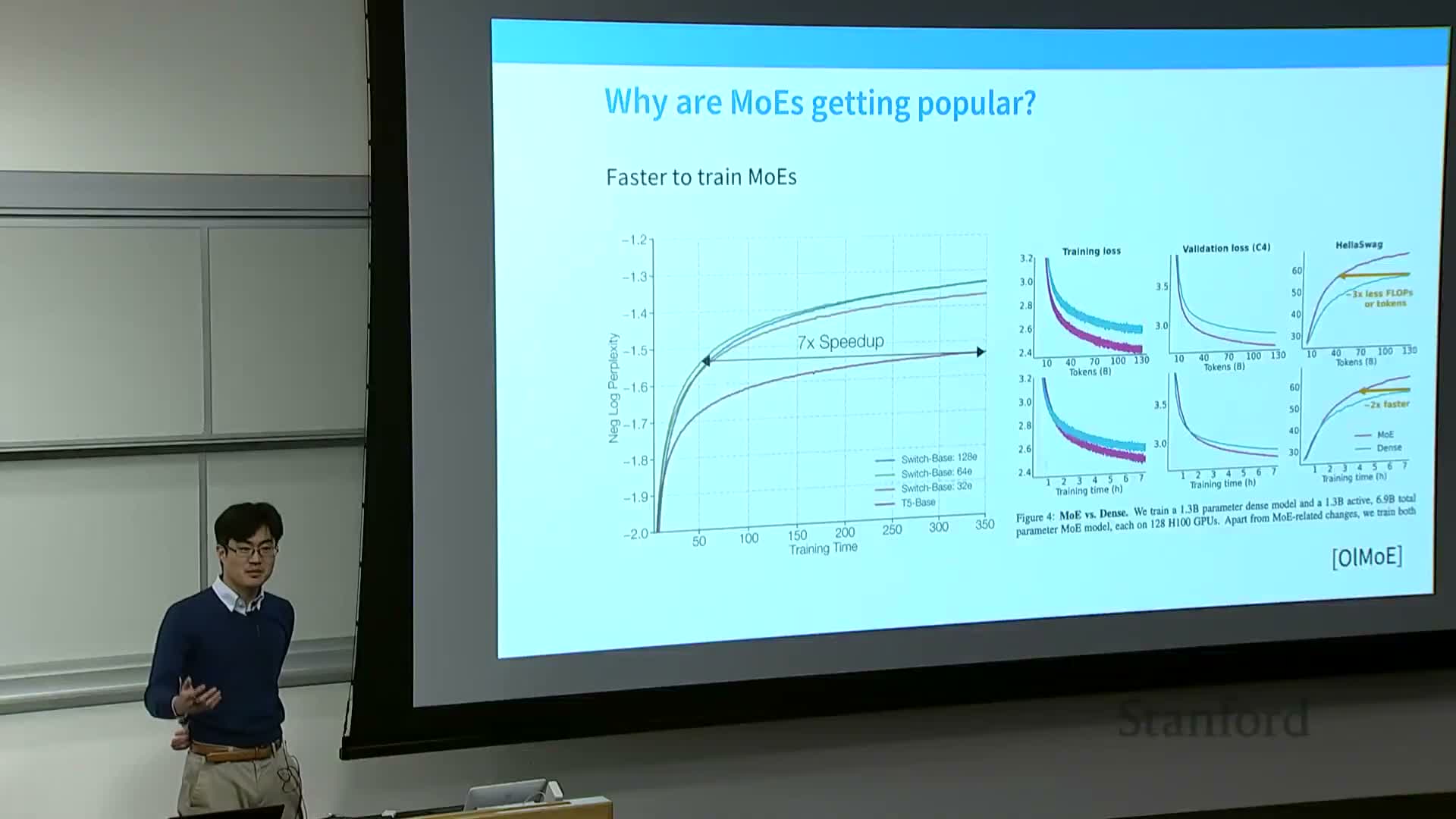

Empirical results show that increasing the number of experts reduces training loss at matched FLOP budgets

Empirical controlled studies show that, at fixed total training FLOPs, models with more experts tend to achieve lower training and validation loss than dense baselines.

- Published experiments report monotonic improvements in language-model training loss and faster perplexity reduction as expert count grows when compute is matched.

- These results indicate that parameter scaling via sparsity yields statistical gains if training protocols, data volumes, and optimizer settings are controlled.

- The benefits are not free: additional experts increase memory footprint and introduce routing and parallelism complexity that systems engineers must solve.

Multiple independent replications and ablation studies corroborate MoE advantages over dense models across architectures

Follow-up ablations and third-party comparisons replicate and extend the original MoE findings across modern architectures and training regimes.

- Variants such as Switch Transformers, GShard, and other MoE families consistently show FLOP-efficient gains and, in some settings, large convergence speedups.

- Results are robust across many implementation choices, but absolute gains depend on hyperparameters like expert count, top-k routing, and balancing mechanisms.

- The literature emphasizes fair benchmarking by comparing dense vs MoE at fixed FLOP budgets.

Activated-parameter metrics and system-level considerations change how MoE performance is reported and perceived

Many system-oriented evaluations plot activated parameters (subset used per forward pass) vs downstream metrics to highlight MoE’s deployment trade-offs.

- Activated-parameter metrics show that MoE can deliver high task performance with relatively few activated weights at inference time.

- However, reporting only activated parameters hides important costs:

- storing deactivated experts in memory, device placement challenges, and peak memory footprint

-

routing overhead and runtime latency

-

communication patterns required to dispatch tokens to off-device experts

- storing deactivated experts in memory, device placement challenges, and peak memory footprint

- Proper evaluation must include both activated FLOPs and infrastructure costs (routing, memory footprint, multi-device communication).

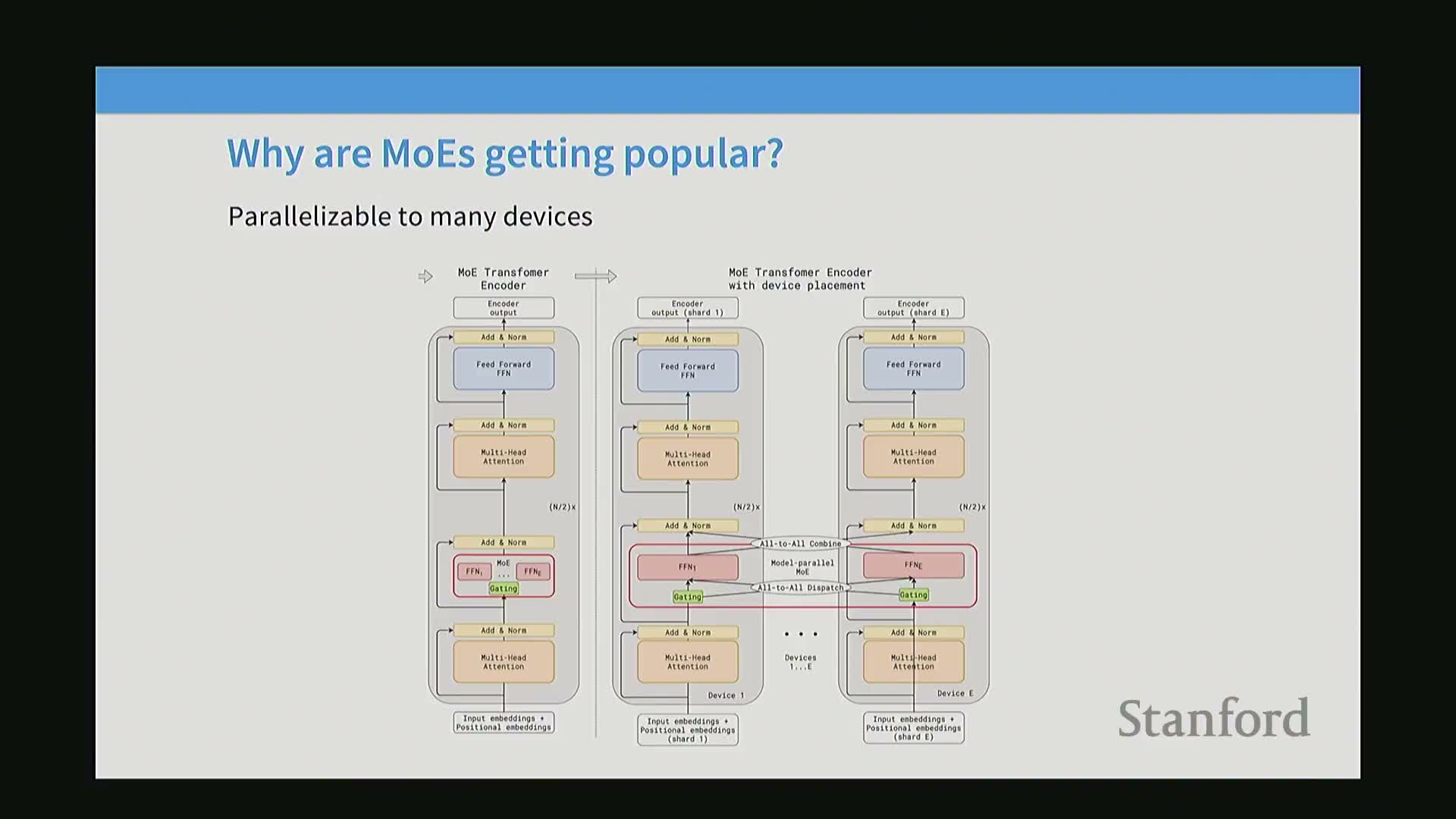

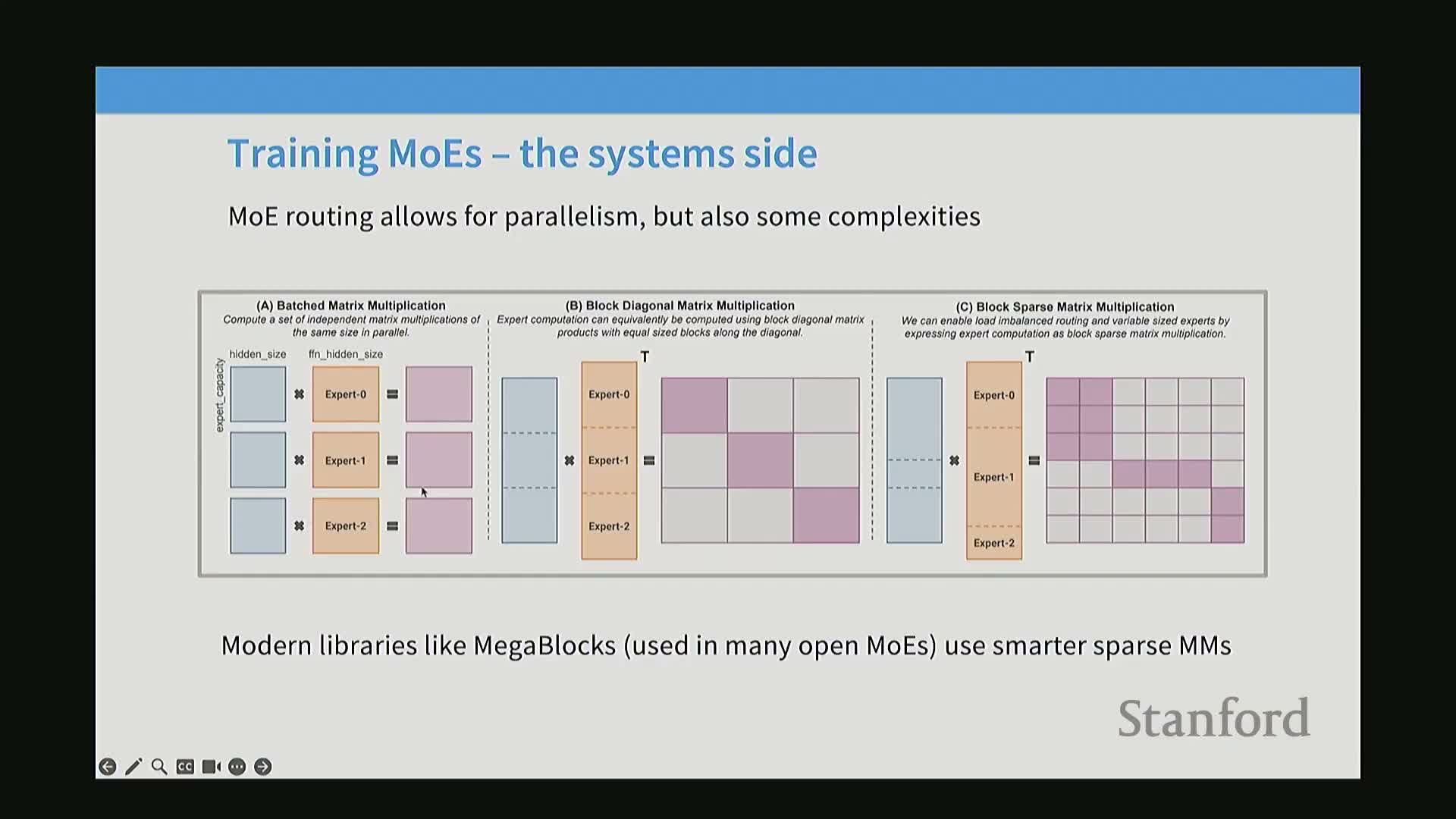

Expert parallelism gives MoE a natural and scalable axis of model parallelism across devices

Expert parallelism shards the model at the granularity of experts by placing different expert MLPs on different devices and routing tokens to the hosting device.

- Because experts are sparsely activated, only devices hosting selected experts participate for a given token set, yielding parallelism beyond data and tensor/model parallelism.

- Benefits:

- reduces per-device memory requirements for very large total-parameter models

- enables use of collective primitives (e.g., all-to-all) to dispatch tokens and gather outputs

- reduces per-device memory requirements for very large total-parameter models

- Requirements for efficiency:

- balanced token assignment across devices

- minimized cross-device communication

- exploitation of fused sparse-matrix operations on modern accelerators

- balanced token assignment across devices

Early open-source and industry efforts (Quen, DeepSeek, Grok, Llama 4) operationalized MoE and introduced practical engineering patterns

Several research groups and industry labs implemented MoE at scale and contributed practical innovations for training and deployment.

- Common innovations:

- methods to upcycle dense models into MoE (copying/perturbing dense weights)

-

fine-grained slicing of experts to increase expert count while keeping per-expert size small

- systems-level routing strategies and communication-balancing techniques

- methods to upcycle dense models into MoE (copying/perturbing dense weights)

- Well-documented large-scale experiments and conversion techniques reduced compute costs while improving performance and helped accelerate community adoption.

- These implementations demonstrate how architectural ideas and systems engineering co-evolve to produce performant end-to-end systems.

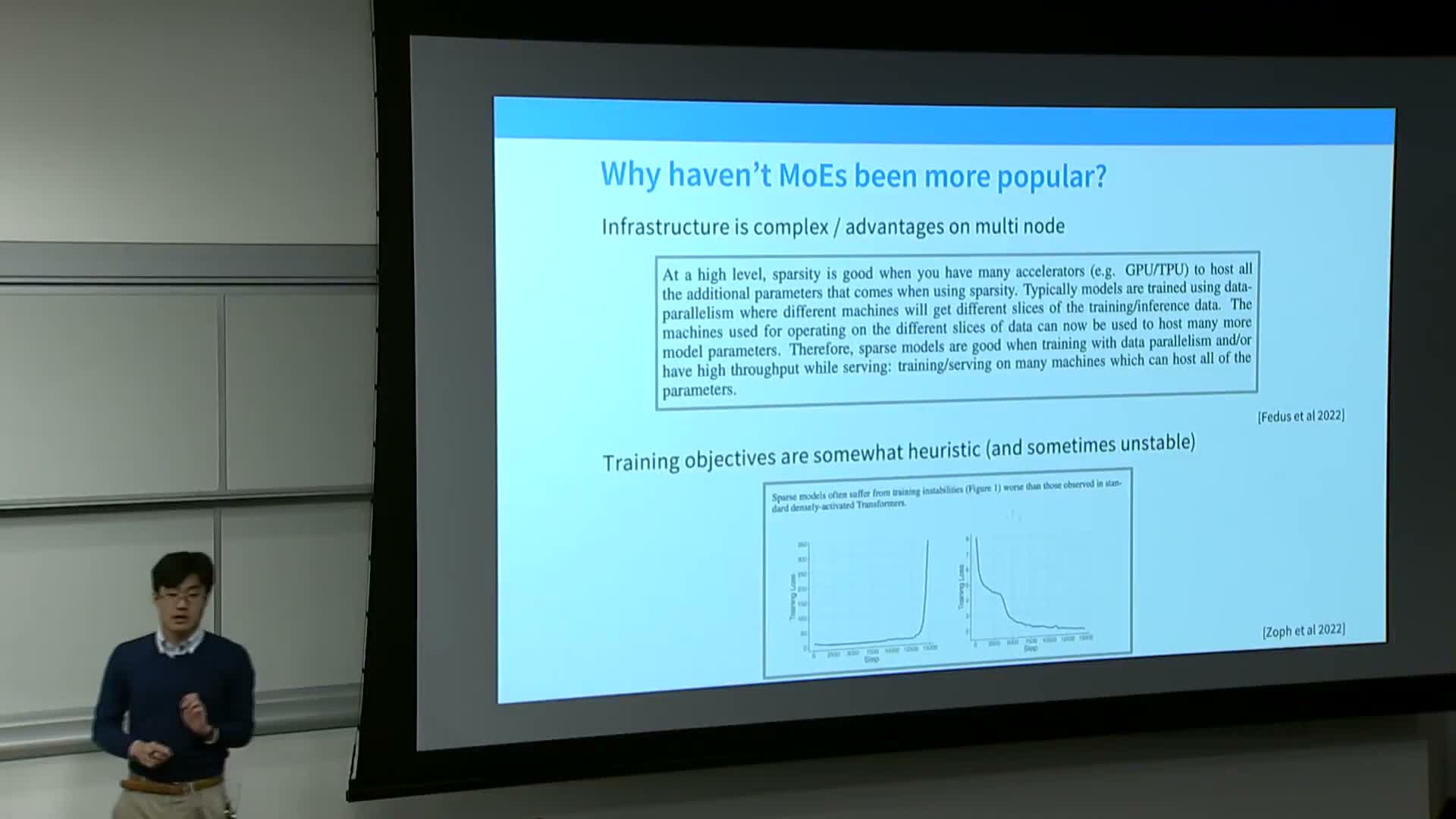

MoE adoption is limited by systems complexity and the discrete non-differentiable routing optimization problem

MoE is not yet a default choice in standard curricula and toolkits because it introduces substantial systems-engineering and optimization challenges.

- The routing decision is discrete and non-differentiable, making router training nontrivial and prone to instability, dead experts, and other pathologies without auxiliary mechanisms.

- Multi-node training is often essential to amortize storage across many experts, increasing communication and placement complexity.

- MoE is most beneficial at large scales where expert parallelism pays off, but it requires significant engineering and tuning to reach those benefits.

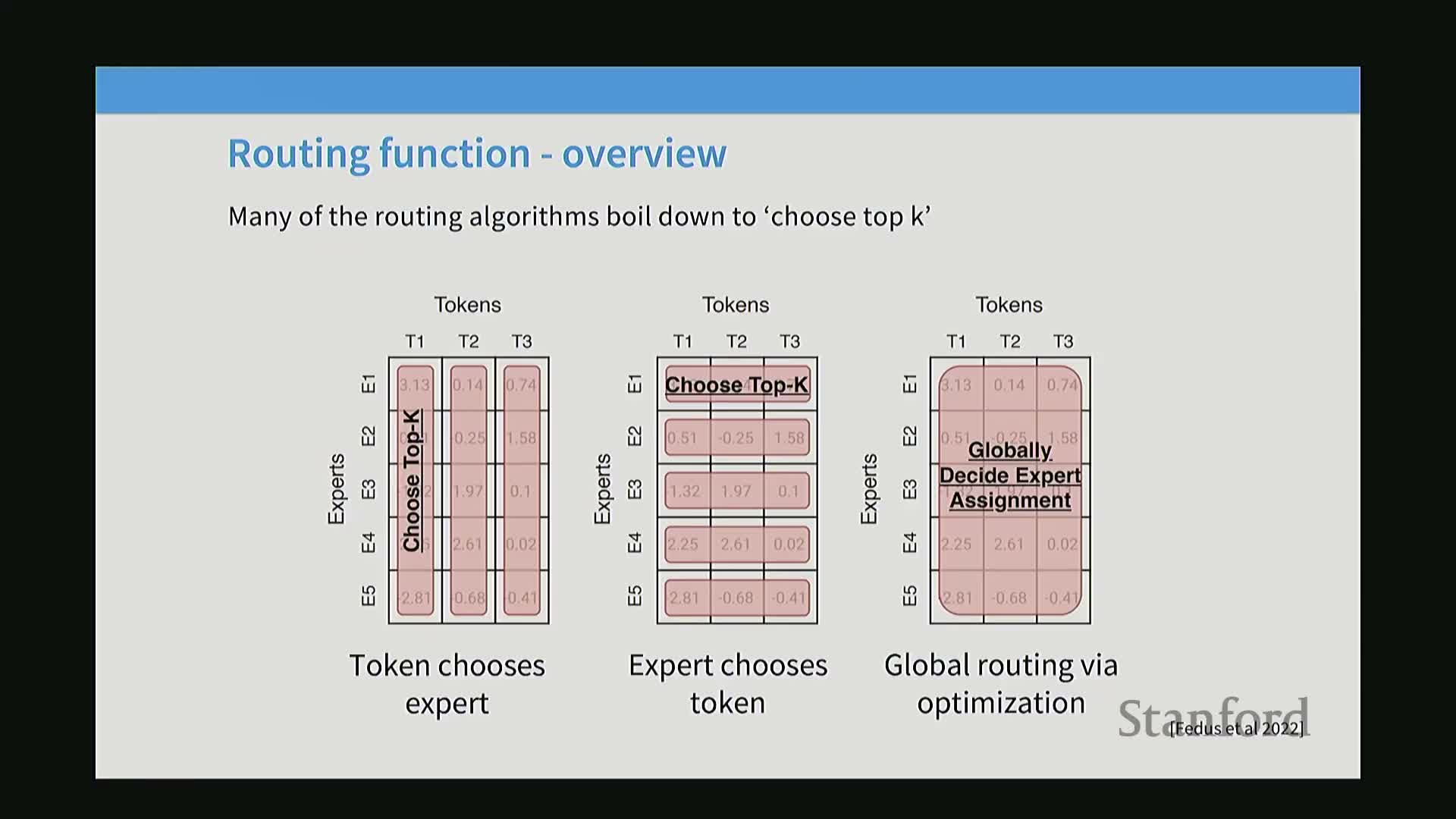

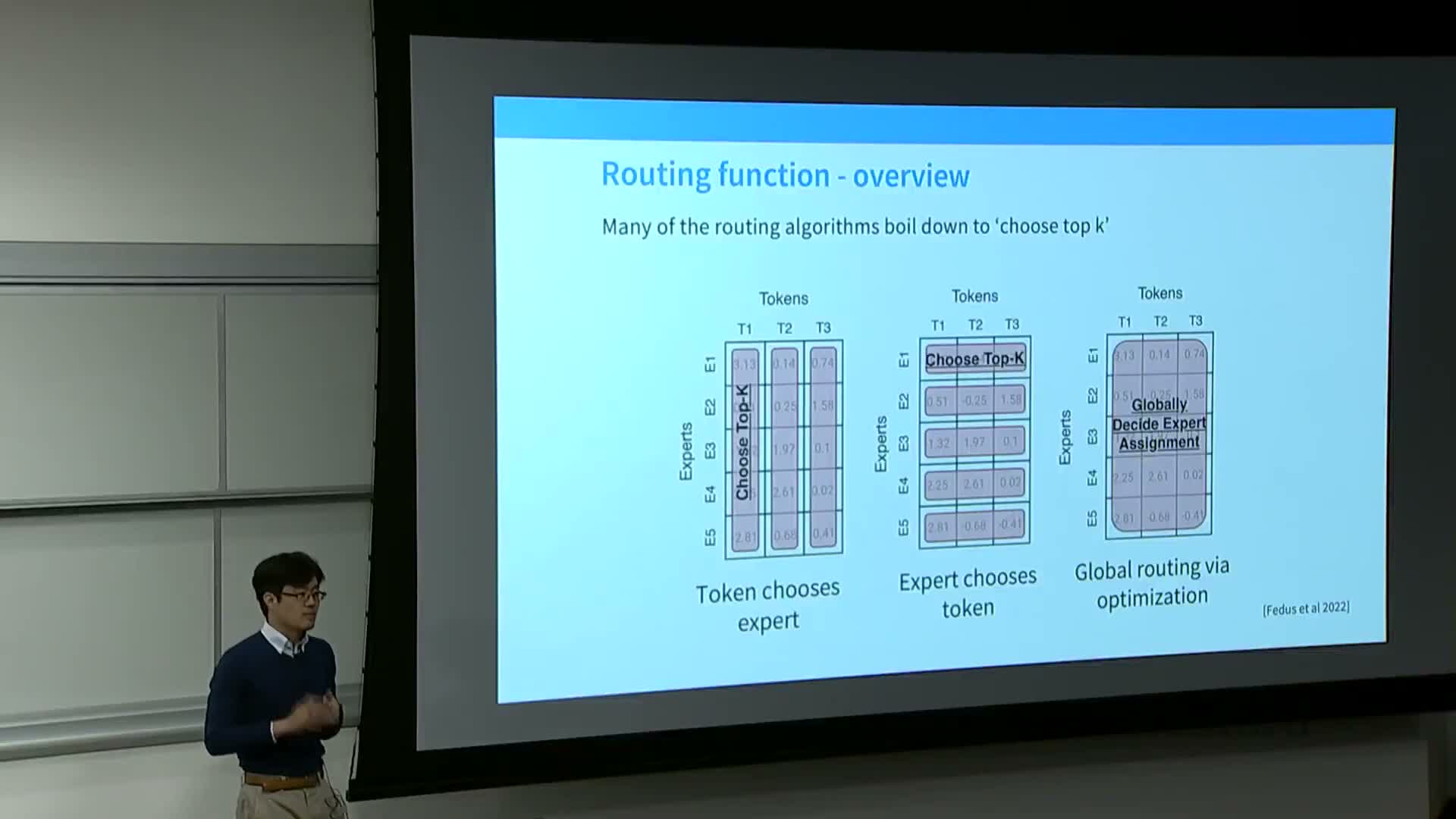

Routing design options include token-choice top-k, expert-choice top-k, and global assignment, with token-choice top-k predominating in practice

Routing policies can be classified into three families:

-

Token-choice: each token ranks experts and selects top-k — widely adopted because it aligns routing with token-level affinities and is straightforward to implement.

-

Expert-choice: each expert selects top-k tokens — provides balanced expert utilization by construction but complicates implementation and data movement.

-

Global assignment: solve a global optimization to balance tokens and affinity — can maximize utilization but is computationally expensive and rarely used at large scale.

Routers are typically lightweight linear scoring functions on the token hidden state and top-k gating combines selected expert outputs

How routers score and combine expert outputs:

- Apply a learned linear projection to the token hidden state and compute inner products with per-expert vectors to produce affinities.

- Optionally apply a softmax to obtain normalized scores.

- Apply a top-k operation to retain only the highest-scoring experts per token.

- Produce gating weights that weight and aggregate selected experts’ outputs (weighted sum or summation after weighting).

- The top-k hyperparameter controls both exploration and FLOPs: k=1 minimizes FLOPs but limits exploration; k=2 is a common practical compromise.

- Implementations vary on normalization (before or after top-k) and whether to use softmax or sigmoids, which affects numerical behavior and system sparsity.

- The top-k hyperparameter controls both exploration and FLOPs: k=1 minimizes FLOPs but limits exploration; k=2 is a common practical compromise.

Non-semantic hashing and simple routing variants can produce empirical gains, indicating that some sparsity benefits derive from capacity partitioning rather than learned semantic routing

Deterministic hashing-based routing can surprisingly improve over dense baselines.

-

Hashing deterministically partitions inputs so each expert receives a reproducible subset and can specialize on frequency or pattern-based distributions.

- This yields effective capacity partitioning even without learned affinity and suggests part of MoE’s benefit is distributed, stable specialization.

- Purely random per-token routing (no deterministic or input-dependent structure) tends to be harmful, while learned or affinity-based partitioning usually yields stronger performance when combined with balancing.

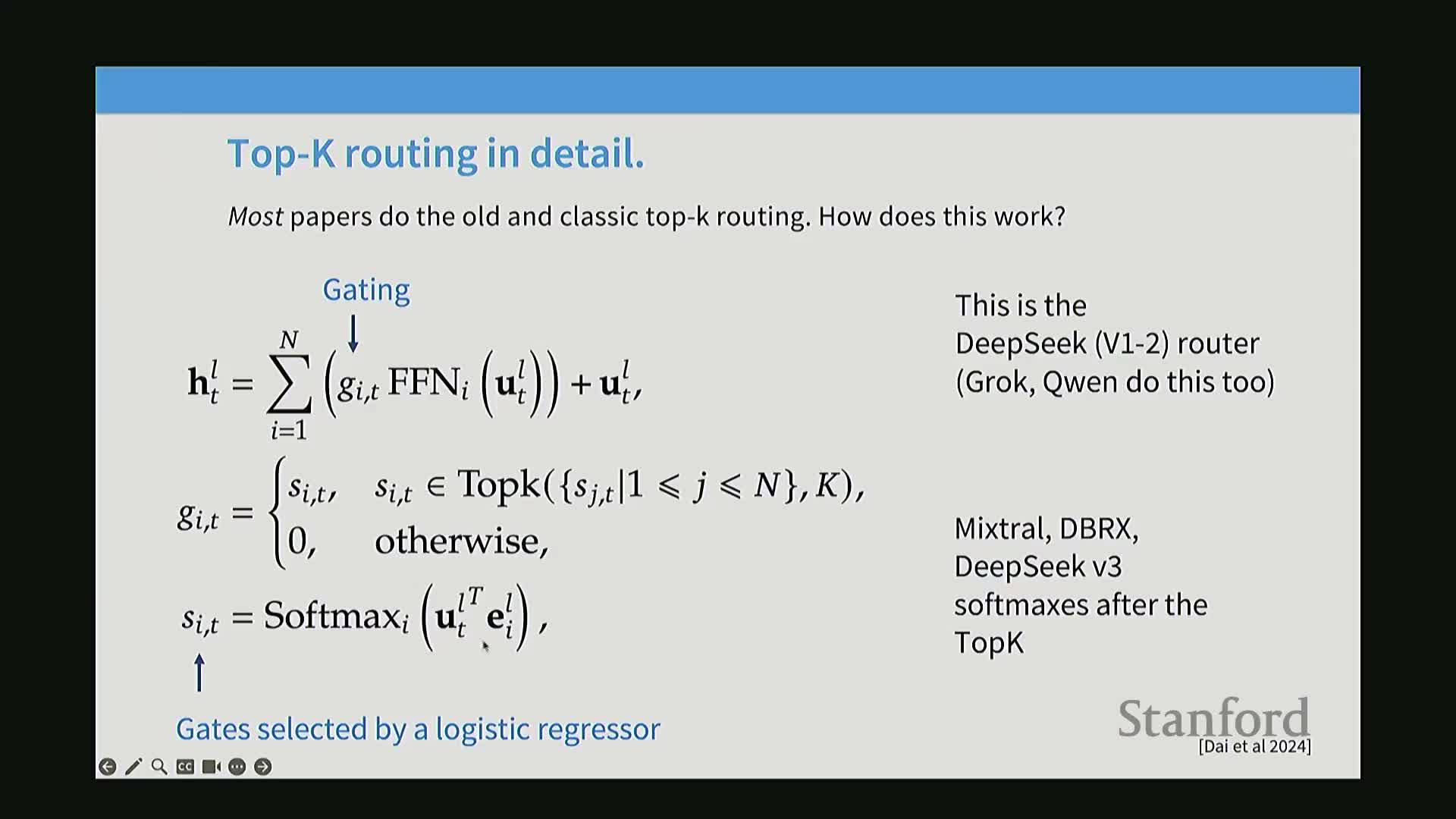

Top-k token-choice routing computes expert affinities via learned expert vectors and softmaxed scores followed by a top-k selection and gated aggregation

Canonical top-k router mechanics (architectural view):

- Score a token hidden state x against learned expert vectors e_i via inner products to produce affinities.

- Normalize affinities (commonly via softmax) to get scores s_i(t).

- Keep the top-k scores per token (top-k operation).

- Form gating weights g from the remaining scores and multiply each selected expert output by its gate.

- Sum the gated expert outputs and add the aggregated sparse MLP output to the residual stream.

- This mirrors attention-like computation but inserts a discrete index selection ensuring only a small subset of experts run per token.

- Implementation decisions include whether to renormalize after top-k and whether to use softmax exponentiation or alternatives for numerical and systems considerations.

- This mirrors attention-like computation but inserts a discrete index selection ensuring only a small subset of experts run per token.

Softmax normalization and top-k interact subtly; normalization preserves weighted averages while top-k enforces sparsity for systems efficiency

Normalization placement and choices matter:

- Applying softmax before top-k yields weights that sum to one and makes the post-aggregation a convex weighted average, which has numerical and stability benefits.

- Applying top-k without renormalization preserves sparsity but can change output scale.

- Eliminating top-k (gating all experts) removes the systems advantage because all experts must be evaluated at each step.

- Alternatives (moving normalization position or replacing softmax with sigmoids) trade off numerical stability, gradient behavior, and systems complexity.

- Practical variants balance training stability, train/infer FLOP constraints, and device communication patterns.

Router complexity is intentionally kept low because routing computation itself must be cheap and learning signals for routing are weak

Router parameterization and routing gradients:

- Routers are typically small linear projections with per-expert vectors rather than deep MLPs to avoid spending FLOPs on routing and reducing MoE’s compute efficiency.

- The learning signal for routing is indirect: gradients primarily flow through selected experts and only weakly update routing parameters via gating comparisons (e.g., top-two), limiting the benefit of more expressive routers.

- More complex router parametrizations (MLP-based) have been studied but rarely justify extra compute and implementation cost at scale.

- Standard design favors minimal, fast scoring layers and focuses engineering effort on balancing, stability, and systems integration.

Fine-grained experts and shared experts enable many more total experts without proportional parameter cost increases

Fine-grained experts and shared experts:

- Fine-grained experts split the canonical FFN projection into many smaller projection slices so each expert is a fraction of the original FFN width, enabling a larger total number of experts for a given parameter budget.

- This increases the breadth of available experts while keeping individual expert size small so activating k experts keeps FLOPs acceptable.

-

Shared experts are a small set of universally applied MLPs that capture common processing components, reducing redundant duplication across experts.

- Ablations show combinations of fine-grained and shared experts often outperform naive copying of dense FFNs and yield practical improvements across tasks.

Common MoE configurations use many fine-grained experts with small per-expert slices and a small number of activated experts per token

Typical large-scale MoE configurations and tuning considerations:

- Deployments commonly use dozens to hundreds of experts, with each expert formed by projecting the FFN down (e.g., quarter-size) to create fine-grained slices.

- Typical public configurations: many fine-grained experts (e.g., 64+) with 2–6 active experts per token and sometimes a few shared experts.

- Effective FLOPs relative to a dense equivalent depend on per-expert size and k; increasing k raises per-step FLOPs and activated-parameter counts proportionally.

- Configurations are tuned via arithmetic accounting for hidden dimensions, projection ratios, and the target activated-FLOPs vs total-parameter trade-offs.

Recap of the MoE forward pass highlights routing, expert selection, gated aggregation, and the residual connection

Forward-pass mechanics (conceptual sequence):

- Router scores a token’s hidden state to produce per-expert affinities.

- A top-k selection restricts active experts for that token.

- Each active expert computes its local MLP output.

- Gating weights scale those outputs.

- A weighted sum is added to the residual stream, preserving transformer identity connections while inserting sparse conditional computation at the FFN location.

- The sequence is simple conceptually, but the discrete top-k step introduces training dynamics and systems consequences that require auxiliary methods for robust optimization.

- Correct implementation must also handle batching, device mapping, and potential load caps per expert to avoid memory blow-ups.

- The sequence is simple conceptually, but the discrete top-k step introduces training dynamics and systems consequences that require auxiliary methods for robust optimization.

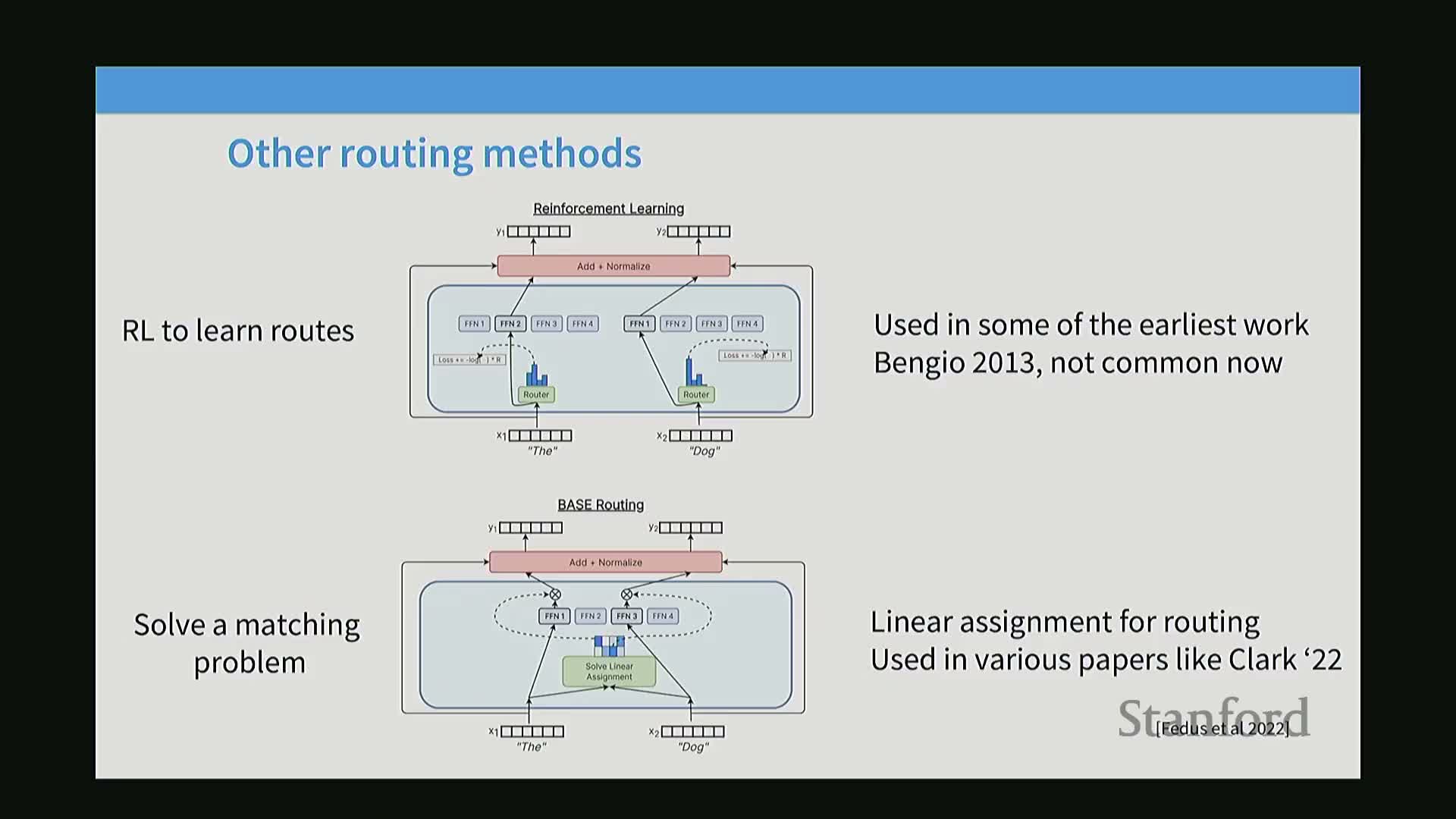

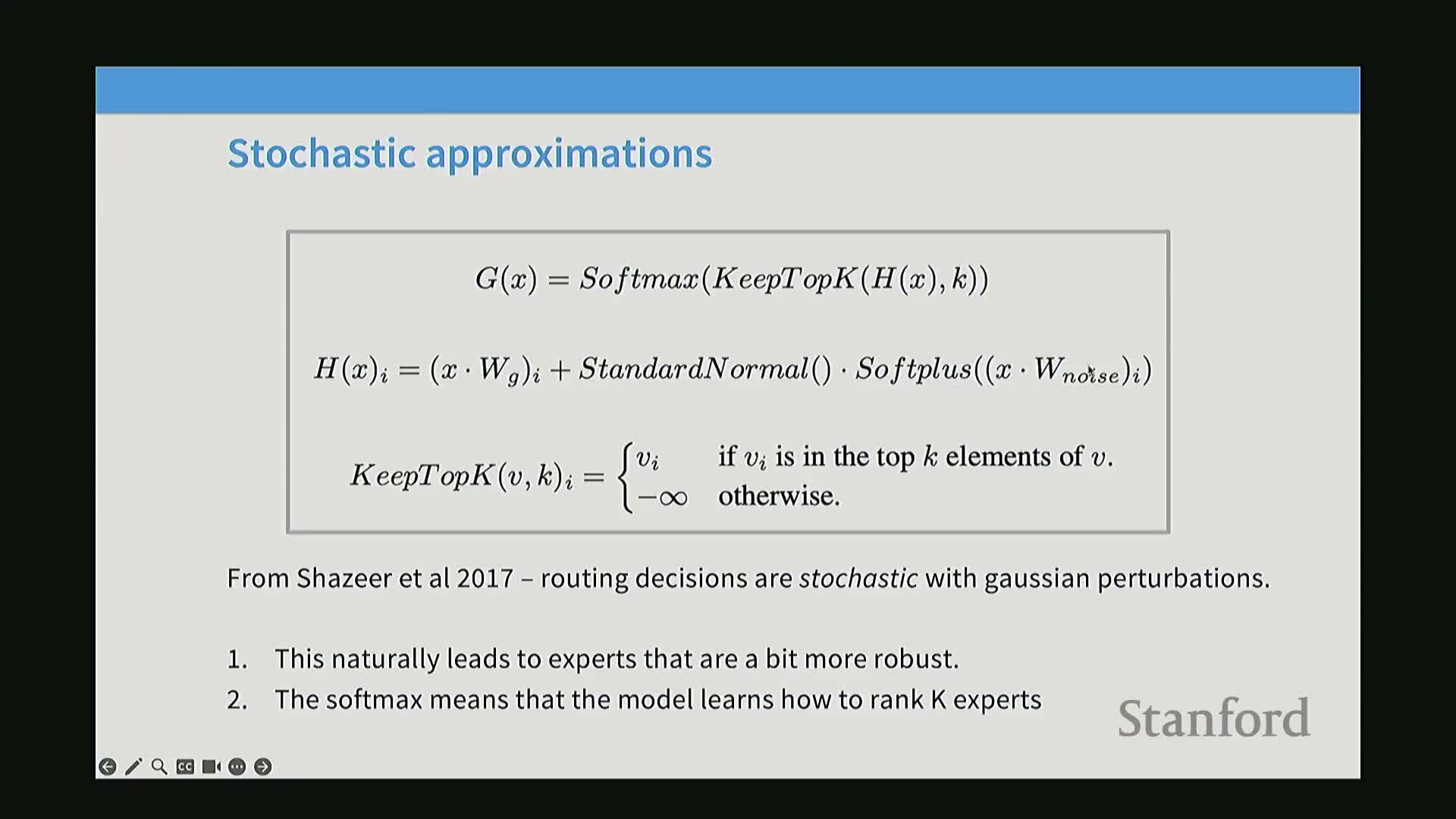

Training MoE is challenging due to non-differentiable sparse decisions, and three practical approaches are RL, stochastic approximation, and balancing heuristics

Optimization approaches for routing:

- Early efforts explored reinforcement learning for router policies, but RL proved unstable, high-variance, and expensive at scale.

-

Stochastic approximations (e.g., jittering logits or sampling from softmax) encourage exploration and reduce dead experts but increase variance and reduce specialization.

- The dominant practical approach: top-k router combined with auxiliary balancing objectives and light stochasticity — these heuristic regularizers scale efficiently and provide effective signals to distribute load and promote specialization.

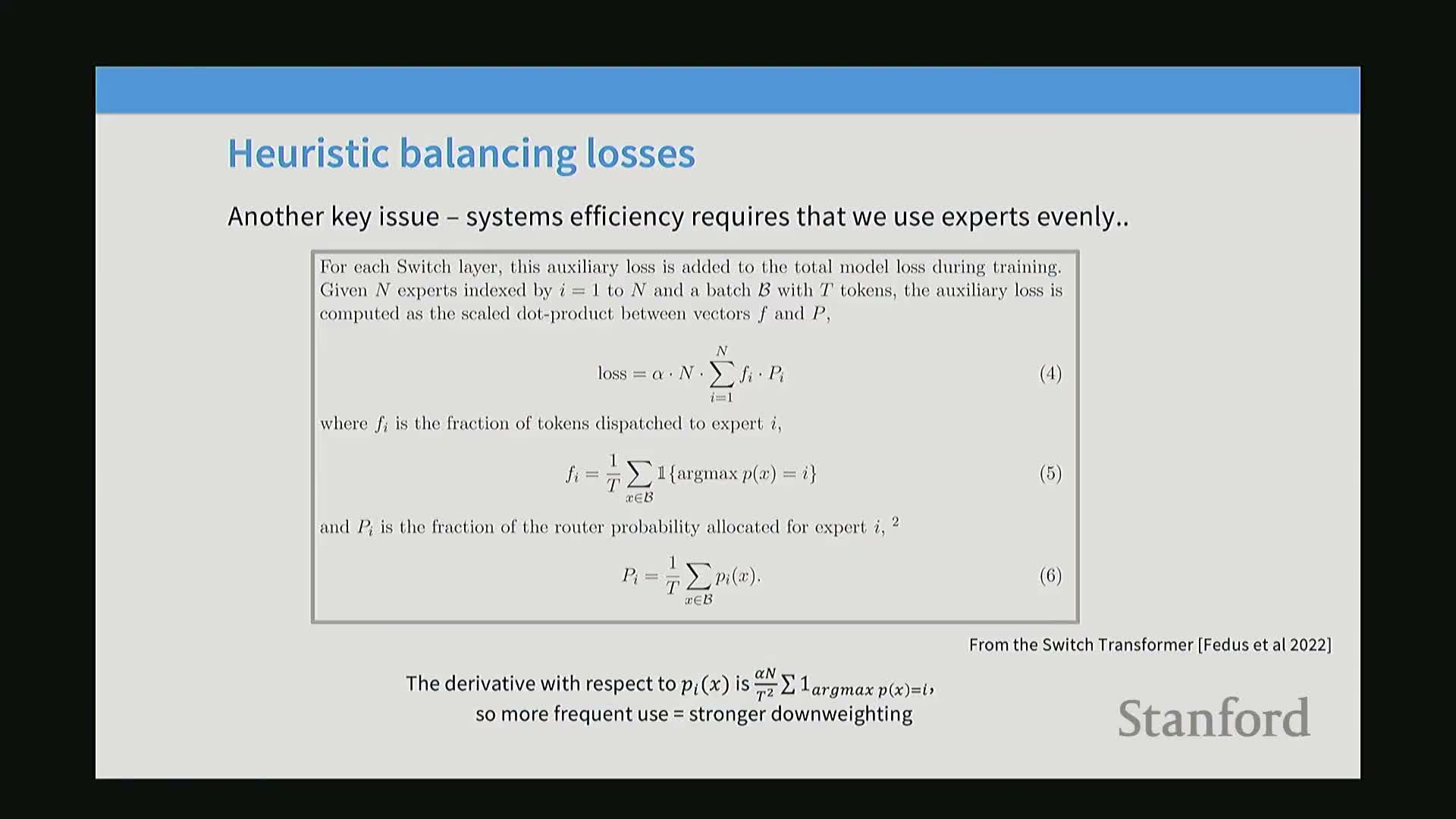

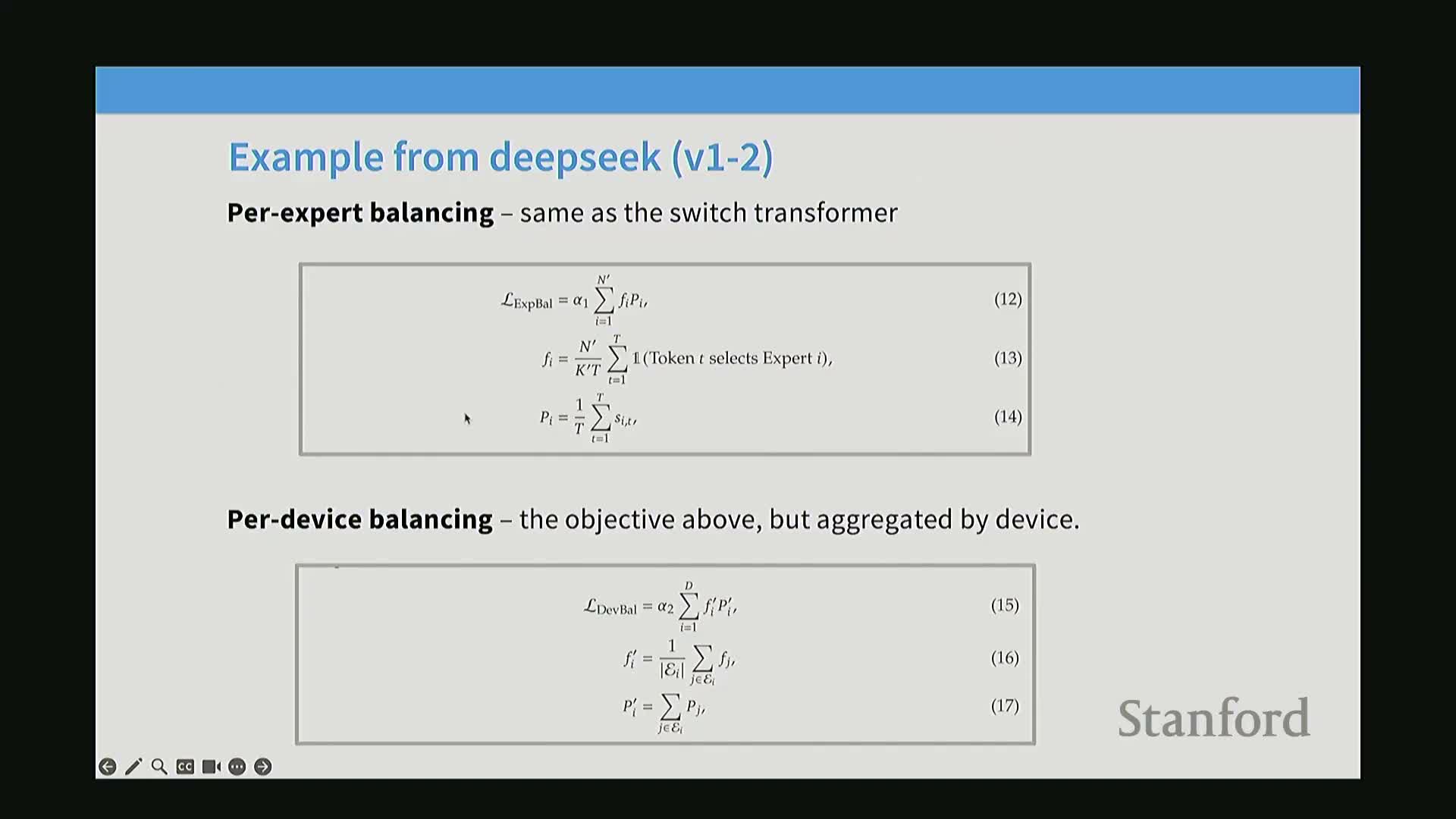

Balancing losses (f · p) are the practical standard to prevent expert collapse and ensure even utilization across batches and devices

A common auxiliary balancing loss:

- Compute an inner product between vector f (actual token fractions assigned to each expert) and vector p (router-assigned probabilities) to produce a penalty that encourages more even token allocation across experts.

- The derivative penalizes overutilized experts proportionally to their token share, discouraging collapsed solutions where a few experts dominate.

- Balancing can be applied at multiple granularities (per-batch, per-device) to match systems placement and is cheap to compute, making it foundational in production MoE systems.

Auxiliary loss-free balancing (per-expert offsets b_i) is an alternative learned online offset scheme used in modern MoE implementations

Learned per-expert bias offsets as an alternative/complement to explicit balancing losses:

- Add learned bias offsets b_i to router scores before ranking and update these offsets online:

-

Increase bias for underutilized experts

-

Decrease bias for overutilized experts

-

Increase bias for underutilized experts

- Offsets act as cheap per-expert incentives that steer routing toward balanced usage without a global auxiliary loss.

- Practical systems often use a hybrid: learned offsets plus occasional auxiliary losses, because per-batch bias updates alone may not ensure per-sequence balancing at inference time.

- Online-offsets reduce gradient coupling and can simplify optimization while addressing utilization and device-level load concerns.

Per-expert balancing is necessary even without systems constraints because routers otherwise deaden many experts and effectively reduce model capacity

The danger of missing early balancing:

- If balancing is not enforced early, routers often route most tokens to a small subset of experts, leaving others with near-zero gradients (dead experts).

- Dead experts reduce effective capacity and waste memory, harming final performance even without considering device-level parallelism.

- Balancing mechanisms therefore serve both optimization and systems roles: they ensure statistical usage of parameters and reduce early routing collapse risk.

- Empirical ablations show large differences in utilization and loss trajectories when balancing is disabled.

Expert placement and communication create batching-dependent stochasticity and token dropping that can affect determinism and outputs

Cross-device routing, token dropping, and non-determinism:

- When experts reside on different devices, collective communication (e.g., all-to-all) moves tokens to expert devices and gathers outputs back.

- High local load can exceed token quotas, causing token dropping where excess tokens are skipped or zeroed—this makes outcomes depend on batch composition and ordering, introducing non-determinism even at zero temperature.

- Mitigations:

-

Load-factor limits and device-level balancing

- Careful batching strategies to stabilize per-batch routing

- Efficient on-device execution using fused sparse-matrix ops to avoid excessive overhead

-

Load-factor limits and device-level balancing

- Operational deployments must account for variability due to cross-batch interactions and communication constraints.

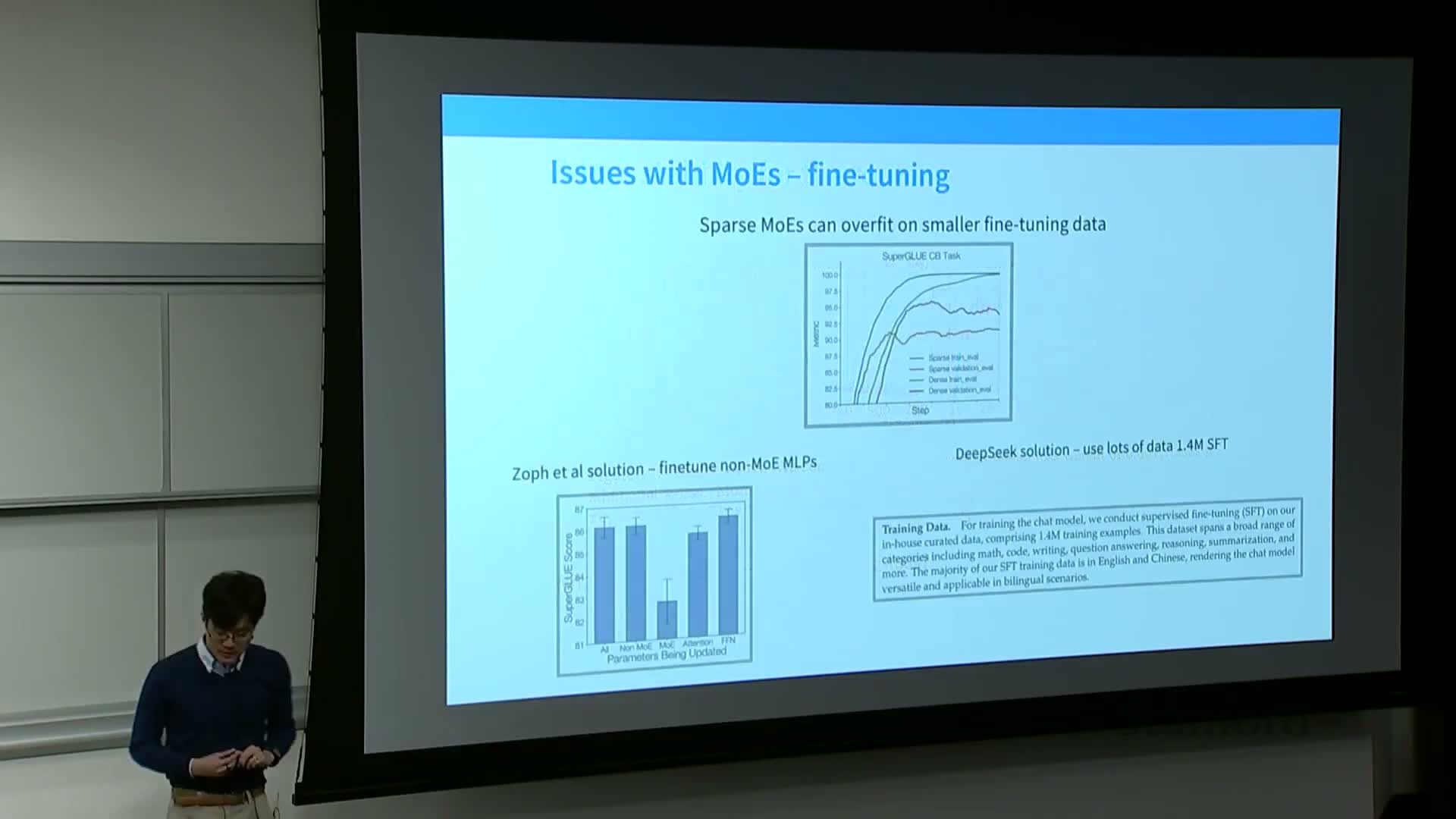

MoE models exhibit training instability and fine-tuning fragility that require numerical and architectural stabilization techniques

Numerical stability, fine-tuning, and upcycling:

- Router logits and gating softmaxes are numerically sensitive and can cause validation loss spikes if not stabilized; common practices:

- compute router logits in float32

- add z-loss or log-normalizer penalties to keep softmax normalizers near one

- use careful initialization of routing biases

- compute router logits in float32

- Sparse models can overfit more readily during fine-tuning due to very large, localized parameter counts. Mitigations:

- alternate dense and sparse layers so fine-tuning primarily alters dense components

- massively increase fine-tuning data to reduce overfitting

- alternate dense and sparse layers so fine-tuning primarily alters dense components

-

Upcycling (initialize experts by copying and perturbing a pre-trained dense FFN and train a new router) offers a cost-effective path to deploy high-capacity MoE models without training from scratch.

DeepSeek v1→v2→v3 exemplifies MoE evolution: consistent core topology with iterative systems and routing refinements such as top-m device selection, communication balancing, KV compression, and multi-token prediction

DeepSeek-style systems and practical refinements for extreme scale:

- Maintain core MoE topology (router + sparse experts) while adding systems and optimization innovations to scale to hundreds of billions of parameters.

- Example refinements (reported in DeepSeek variants):

-

Top-m device selection: router first restricts candidate devices, then selects top-k experts within those devices to reduce cross-device communication

-

Communication-balancing losses that account for input and output transfer costs

- Learned per-expert bias offsets for auxiliary-loss-free balancing

-

Multi-head latent attention (MLA) to project hidden states into a lower-dimensional latent for KV caching efficiency and merged projections to avoid extra FLOPs

- Lightweight multi-token prediction (MTP) heads as small auxiliaries to predict additional future tokens

-

Top-m device selection: router first restricts candidate devices, then selects top-k experts within those devices to reduce cross-device communication

- Combined systems, communication control, and optimization choices (e.g., DeepSeek v3) help stabilize training, manage communication, and realize very large active-parameter models with manageable inference FLOPs and operational cost.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: