CS336 Lecture 5 - GPUs

- Lecture objectives and roadmap

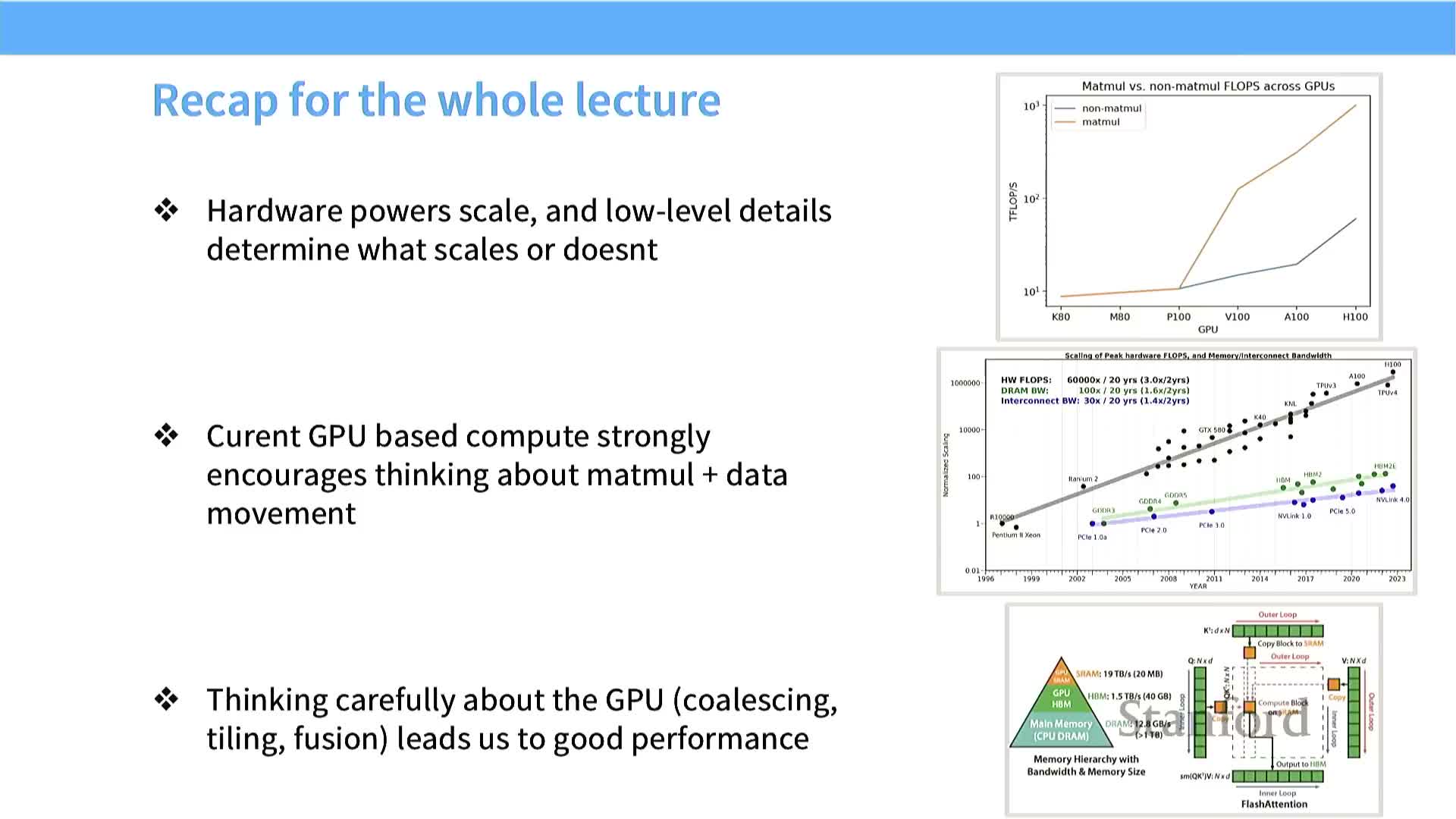

- Compute scaling motivates hardware-focused optimization

- CPUs optimize latency while GPUs optimize throughput

- GPU physical chip structure and memory proximity determine performance

- GPU execution granularity: blocks, warps and threads

- Logical memory model: registers, shared, and global memory

- TPU architecture is conceptually similar to GPUs with MXU specialization

- Matrix multiplies and tensor cores drive GPU value for ML

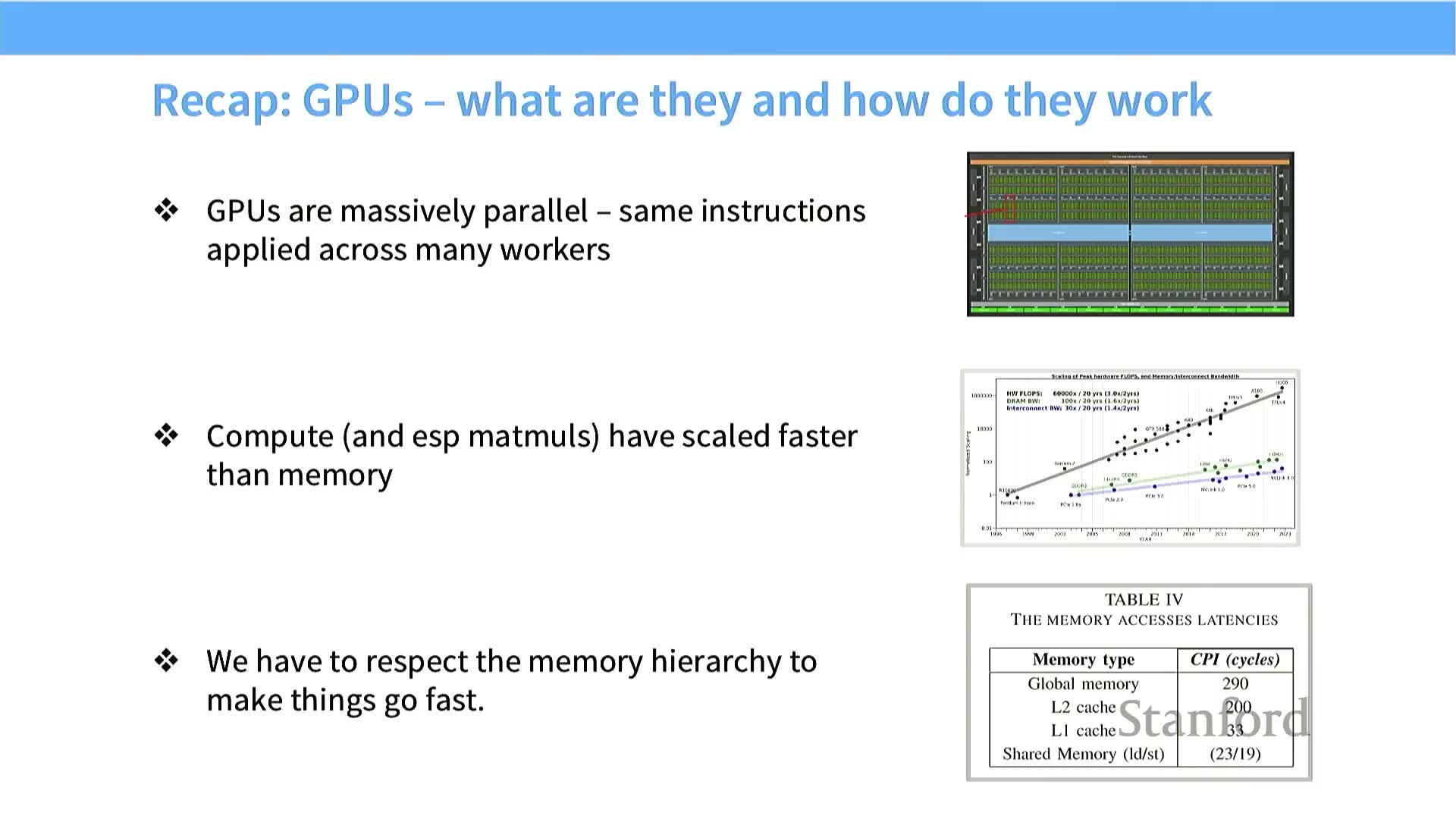

- Compute has outpaced memory growth, making memory movement the bottleneck

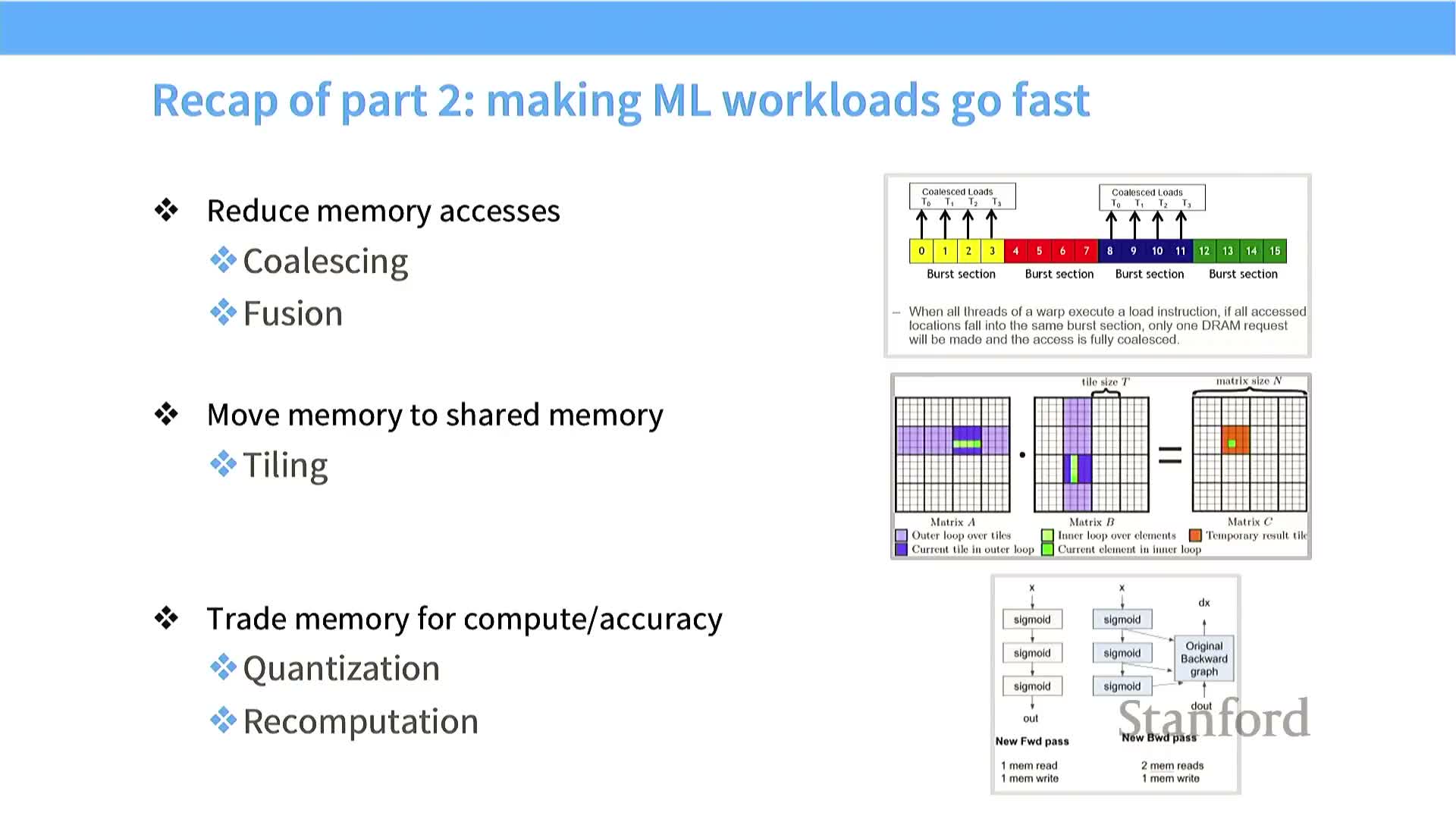

- Summary of GPU characteristics to guide optimization

- Roofline model explains memory- vs compute-bound regimes

- Warp divergence from conditionals degrades throughput

- Lower-precision arithmetic increases effective memory bandwidth

- Operator fusion reduces global memory traffic by composing kernels

- Recomputation trades compute for memory to reduce global accesses

- DRAM burst transfers and memory coalescing shape effective bandwidth

- Tiling reuses on-chip memory to amortize global memory cost

- Tiling arithmetic: global reads scale with N/T and shared reads scale with T

- Tile-size discretization and alignment cause large throughput variance

- Wave quantization: tiles, SM count and occupancy create cliffs

- Practical optimization checklist for GPU kernels

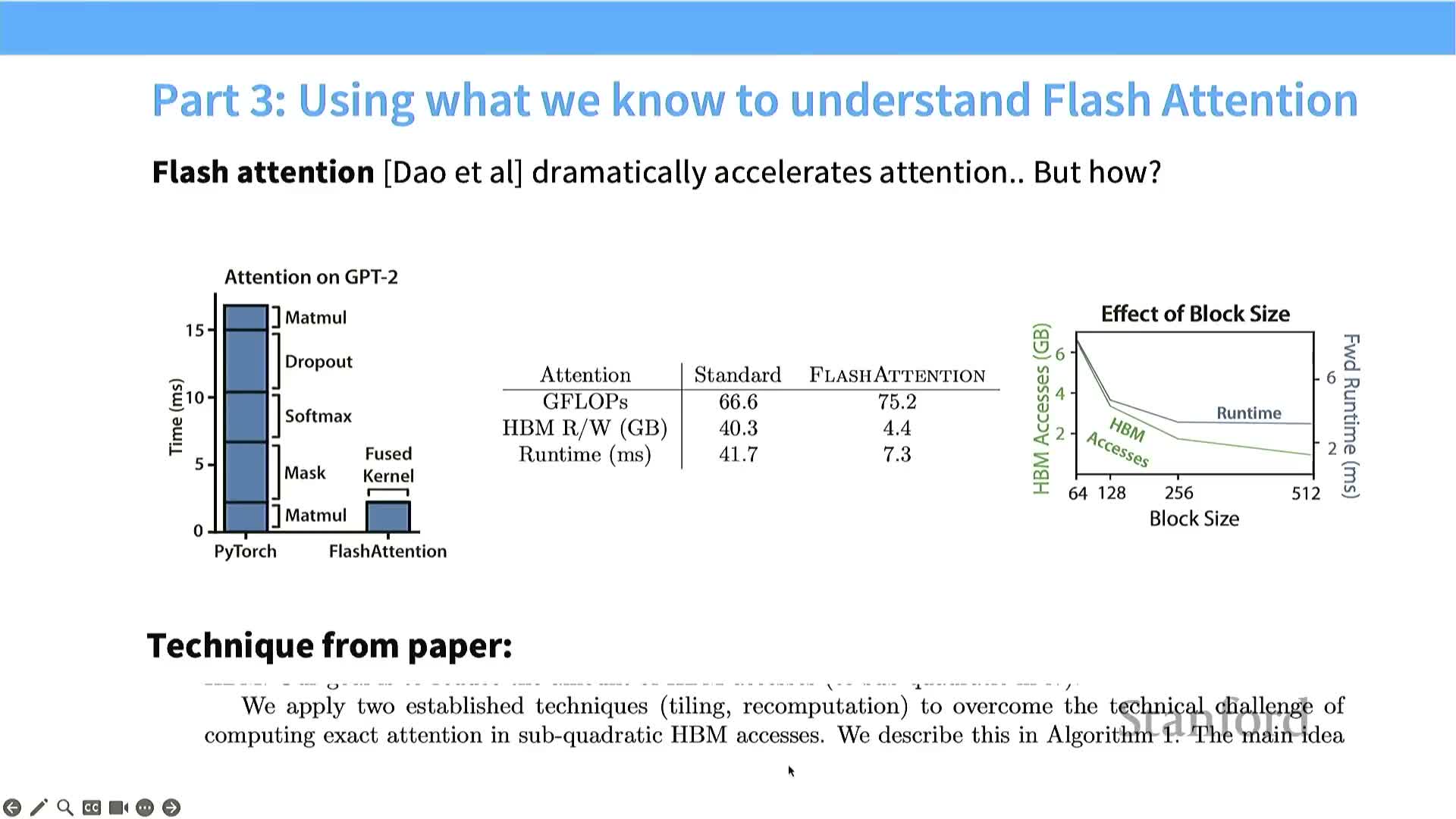

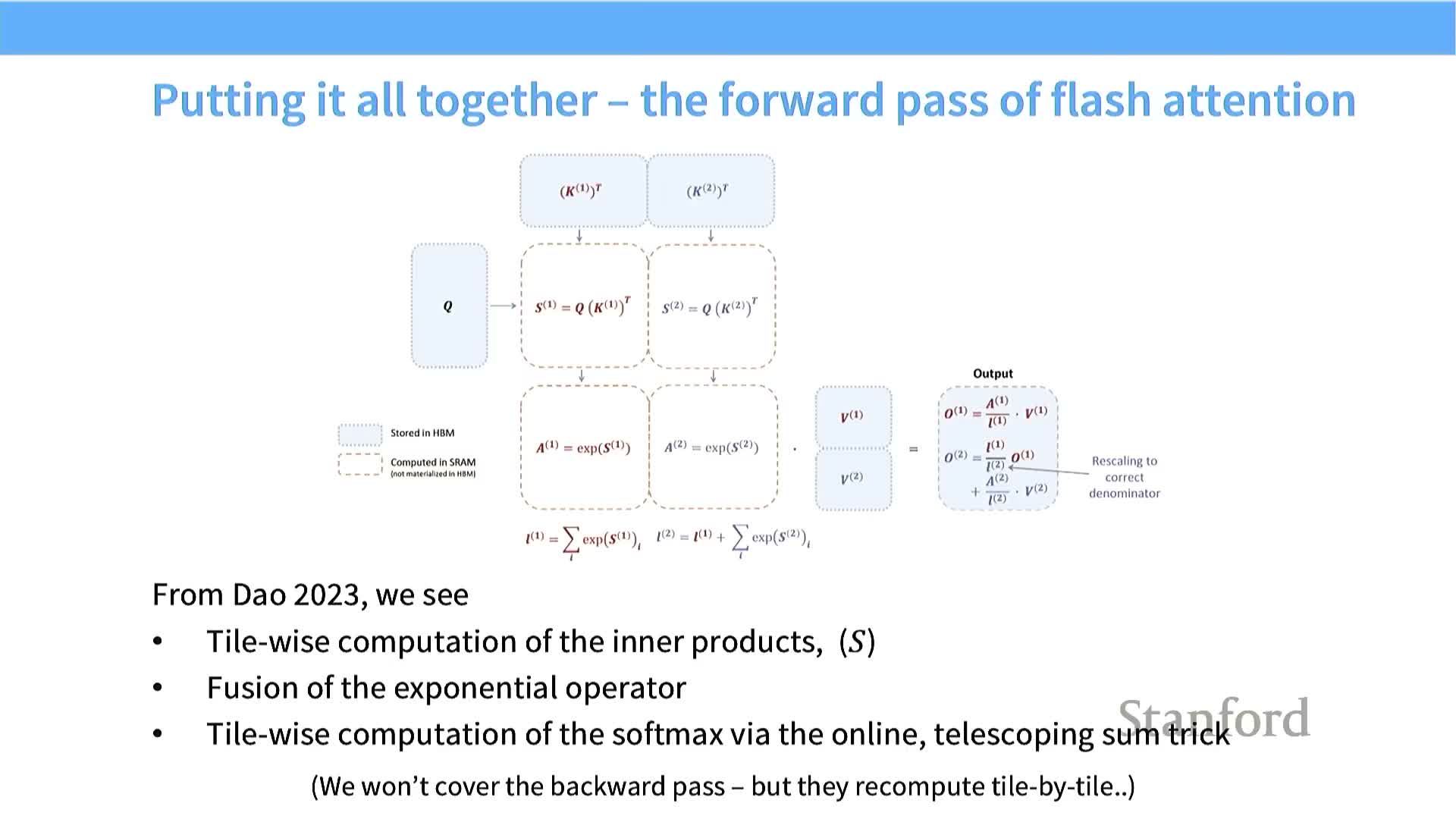

- Flash Attention uses tiling and recomputation to reduce HBM accesses for attention

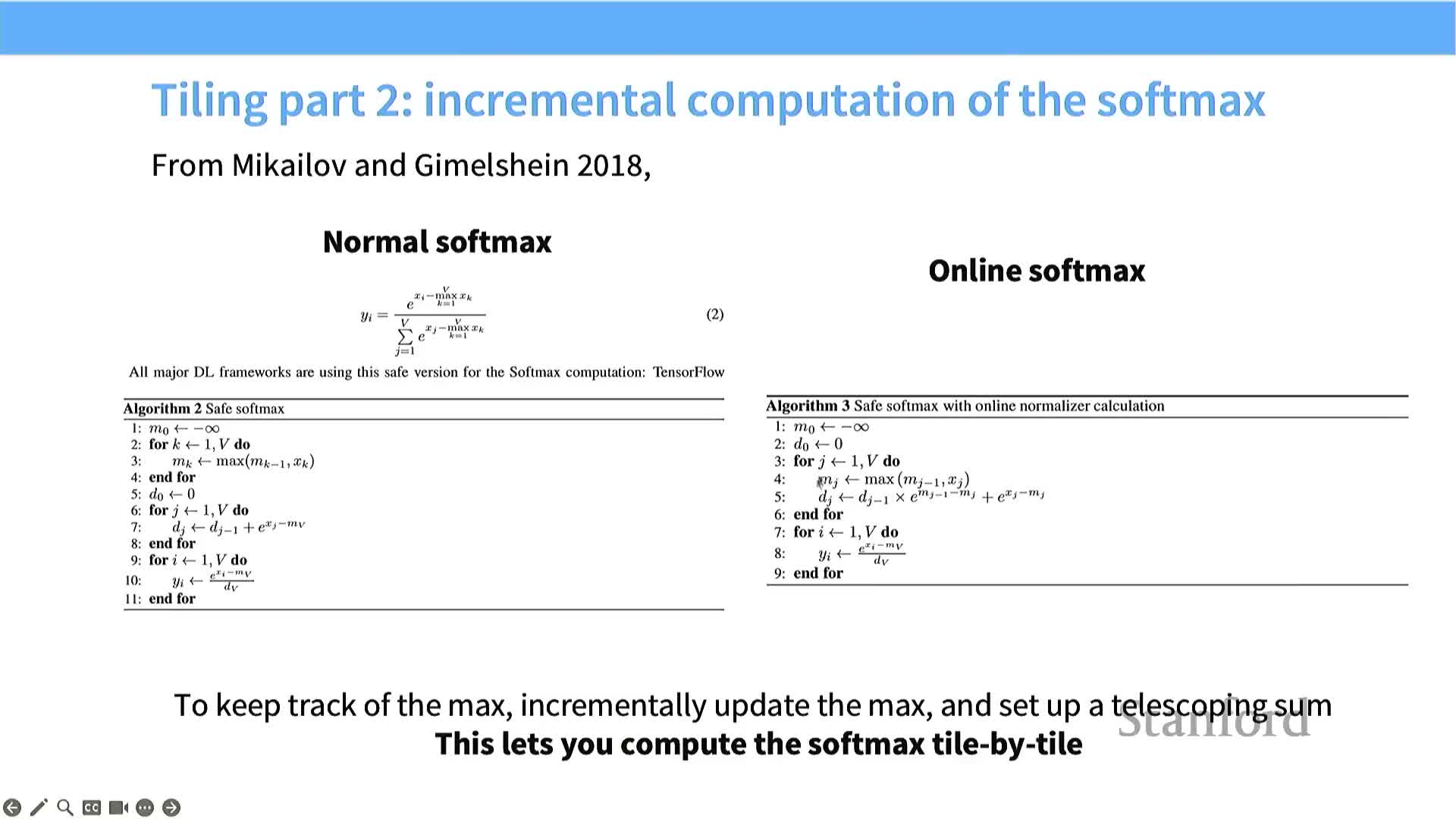

- Attention computation is tiled but softmax is a global normalization challenge

- Online softmax enables tile-by-tile softmax computation

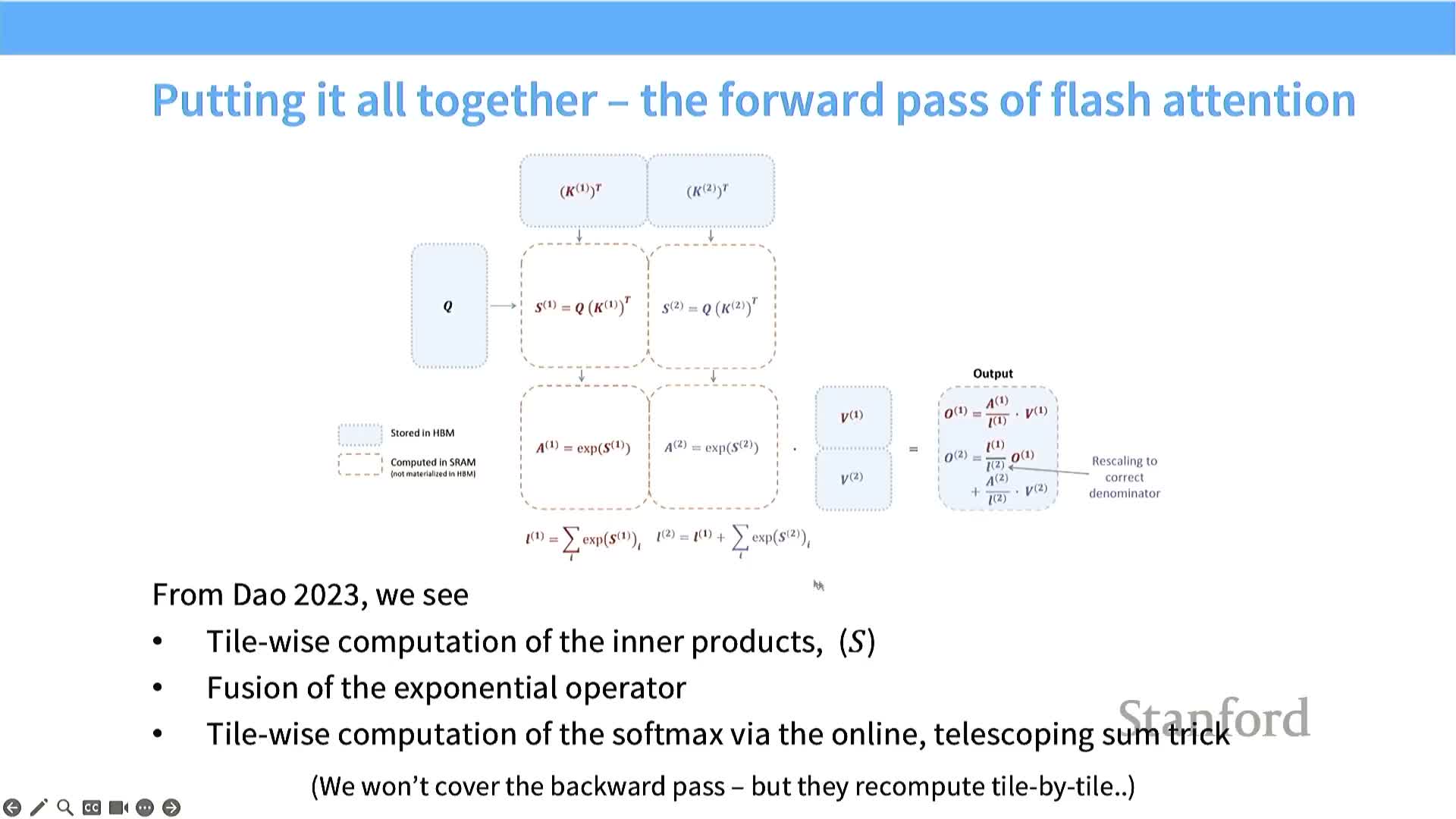

- Flash Attention integrates tiled matmuls and recomputation for forward and backward passes

- Final takeaway: optimize data movement first, then compute

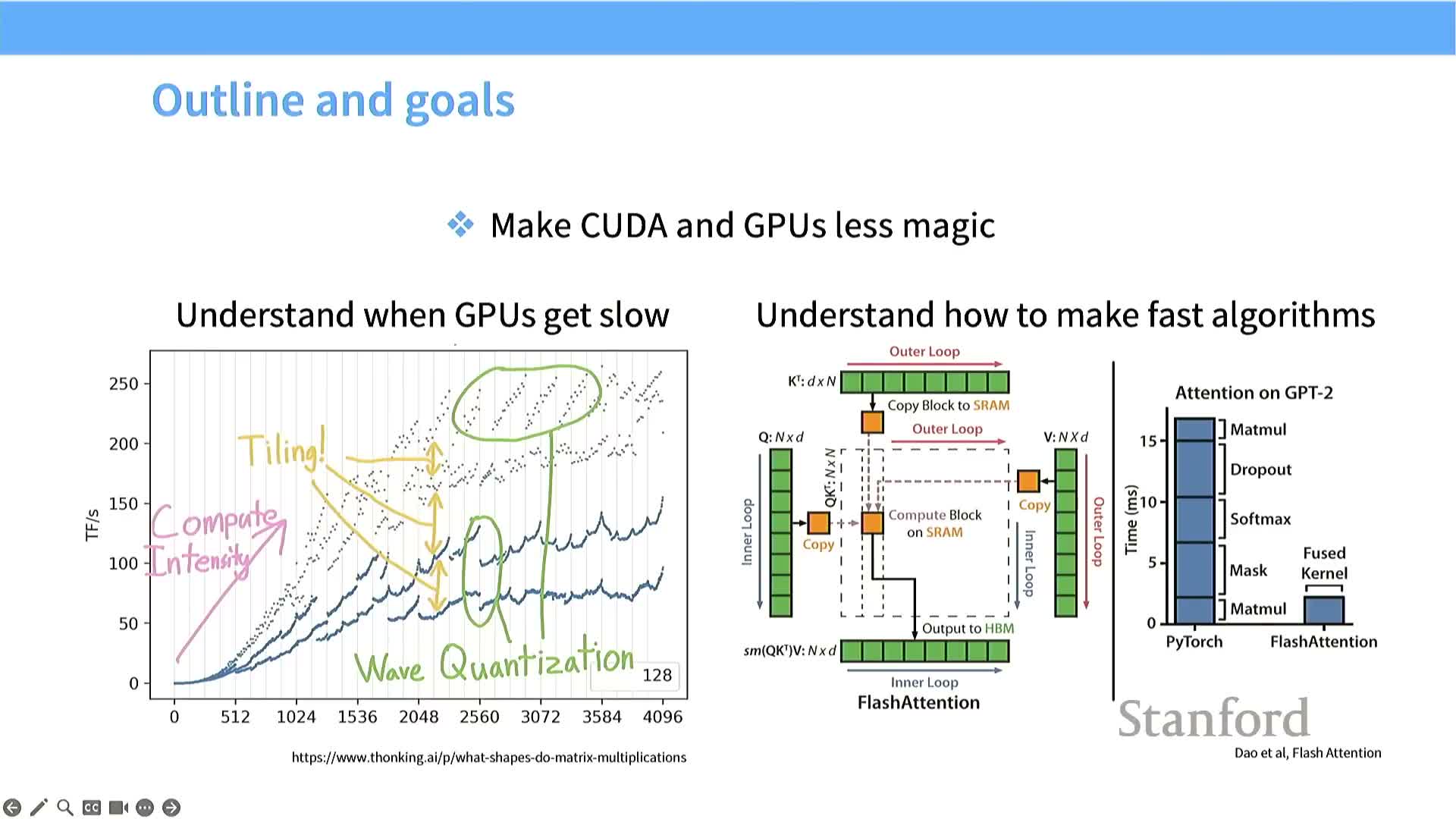

Lecture objectives and roadmap

The lecture introduces the goals: demystify CUDA / GPUs and equip practitioners to accelerate model components with GPU-aware algorithms and implementations.

Roadmap (three parts):

-

Understand GPU hardware and execution model — learn SMs, warps, memory hierarchy, latency vs throughput tradeoffs.

-

Analyze performance characteristics — why GPUs are fast on some workloads and slow on others, and how to measure bottlenecks.

-

Apply lessons to implement high-performance primitives — practical examples such as Flash Attention.

The segment also frames assignments and resources for deeper study, and sets expectations for the remainder of the talk.

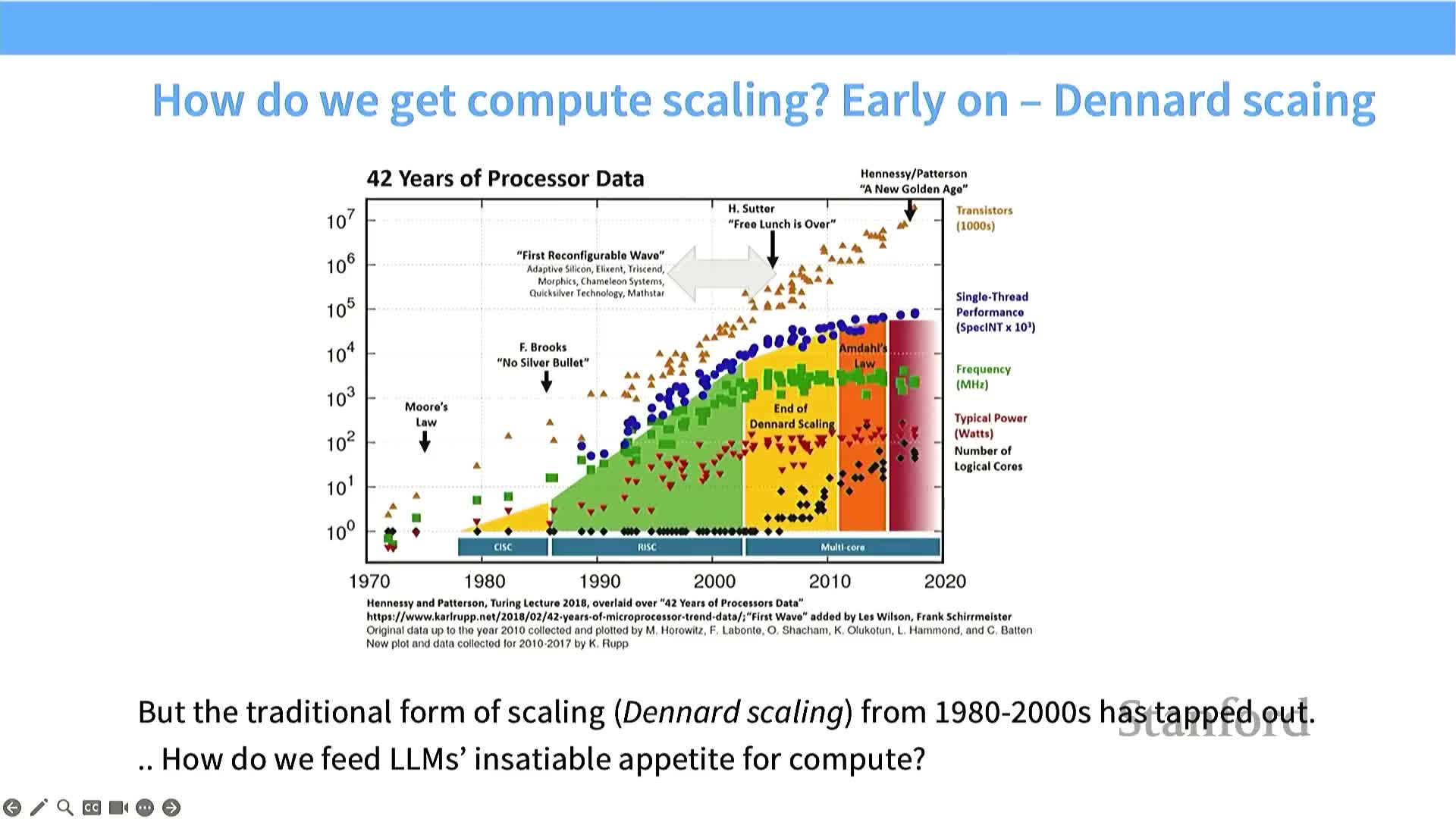

Compute scaling motivates hardware-focused optimization

Compute scaling and historical semiconductor trends explain why parallel hardware matters for modern deep learning workloads.

-

Dennard scaling and Moore’s Law drove decades of single-thread frequency and IPC increases.

- When single-thread throughput plateaued, the performance story shifted to parallel scaling across many cores.

- The result: exponential growth in aggregate integer / FLOP throughput across GPU generations.

- Consequence: efficient utilization of massively parallel accelerators is the key lever for model scaling and performance.

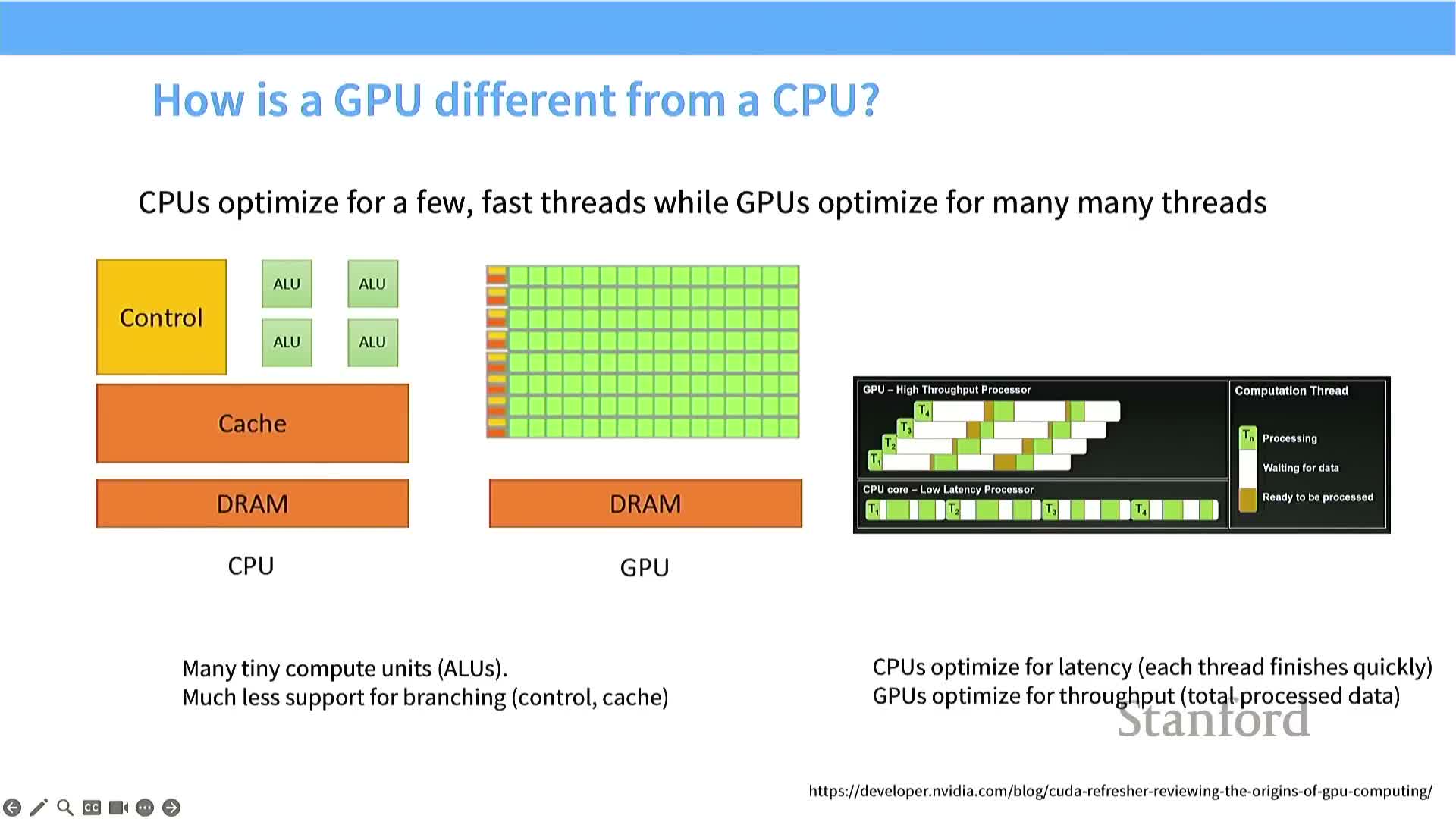

CPUs optimize latency while GPUs optimize throughput

CPUs and GPUs are architected for different goals, which dictates different programming and algorithmic approaches.

-

CPUs:

- Allocate significant die area to control logic, branch prediction, and single-thread performance.

- Optimized to minimize latency for individual tasks and handle complex control flow.

- Allocate significant die area to control logic, branch prediction, and single-thread performance.

-

GPUs:

- Trade control for massive numbers of ALUs to maximize aggregate throughput.

- Expose many simple processing elements that execute the same instruction across many data elements (SIMT).

- Deliver extremely high parallel FLOPS at the cost of higher per-thread latency and simplified control.

- Trade control for massive numbers of ALUs to maximize aggregate throughput.

Implication: design for latency-sensitive workloads on CPUs and throughput-oriented workloads on GPUs, with algorithms and kernels matched accordingly.

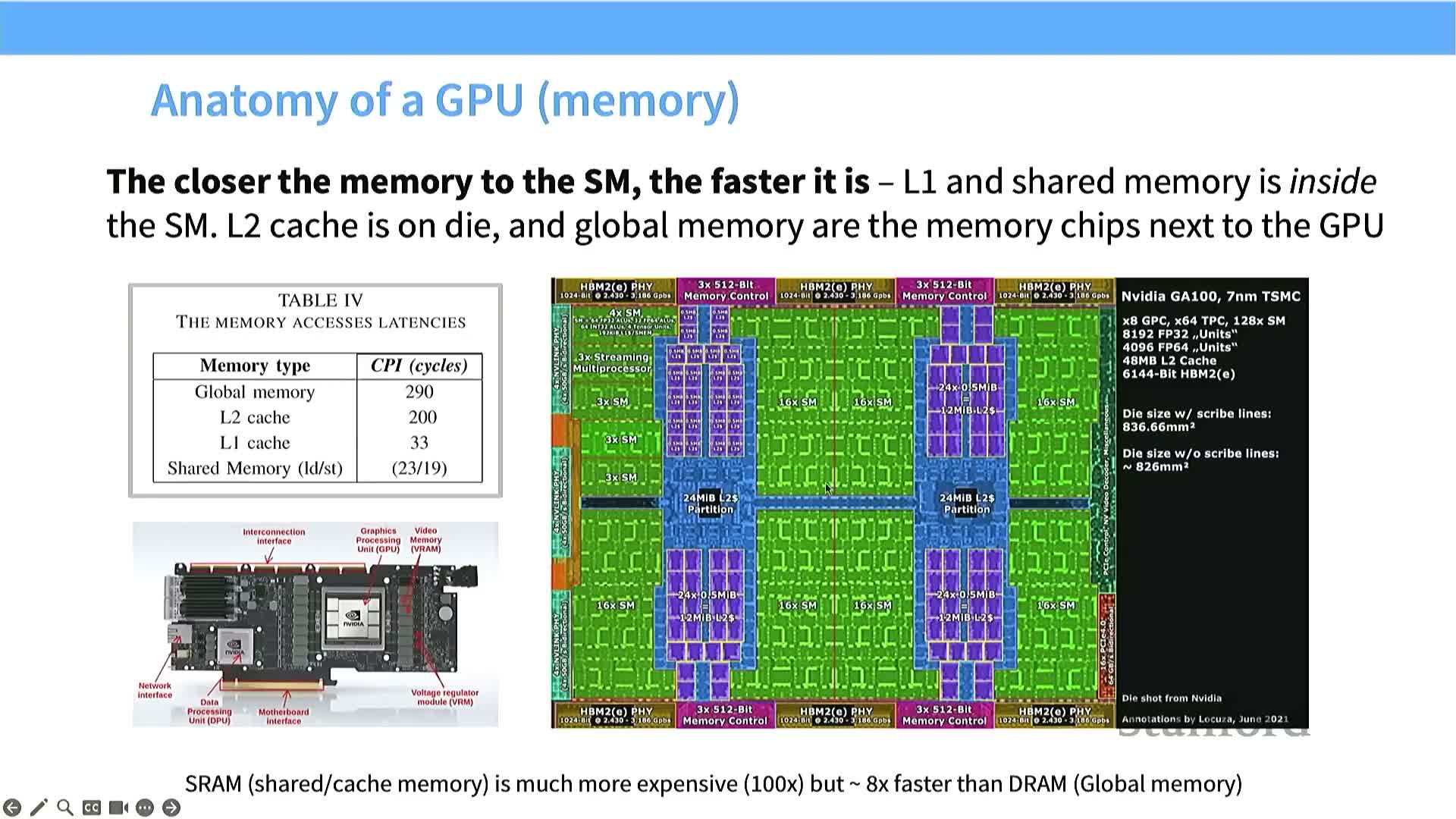

GPU physical chip structure and memory proximity determine performance

A GPU chip is organized into many Streaming Multiprocessors (SMs) with a layered memory system and strong locality considerations.

- Per-SM fast memory: registers, L1, and shared memory (very low latency).

- Chip-level caches and external memory: L2 and external DRAM (HBM or GDDR) (much higher latency).

- Physical proximity matters: on‑SM accesses take tens of cycles, global memory accesses can take hundreds of cycles.

Design implication: minimize transfers from global memory and exploit SM-local storage to keep compute units busy.

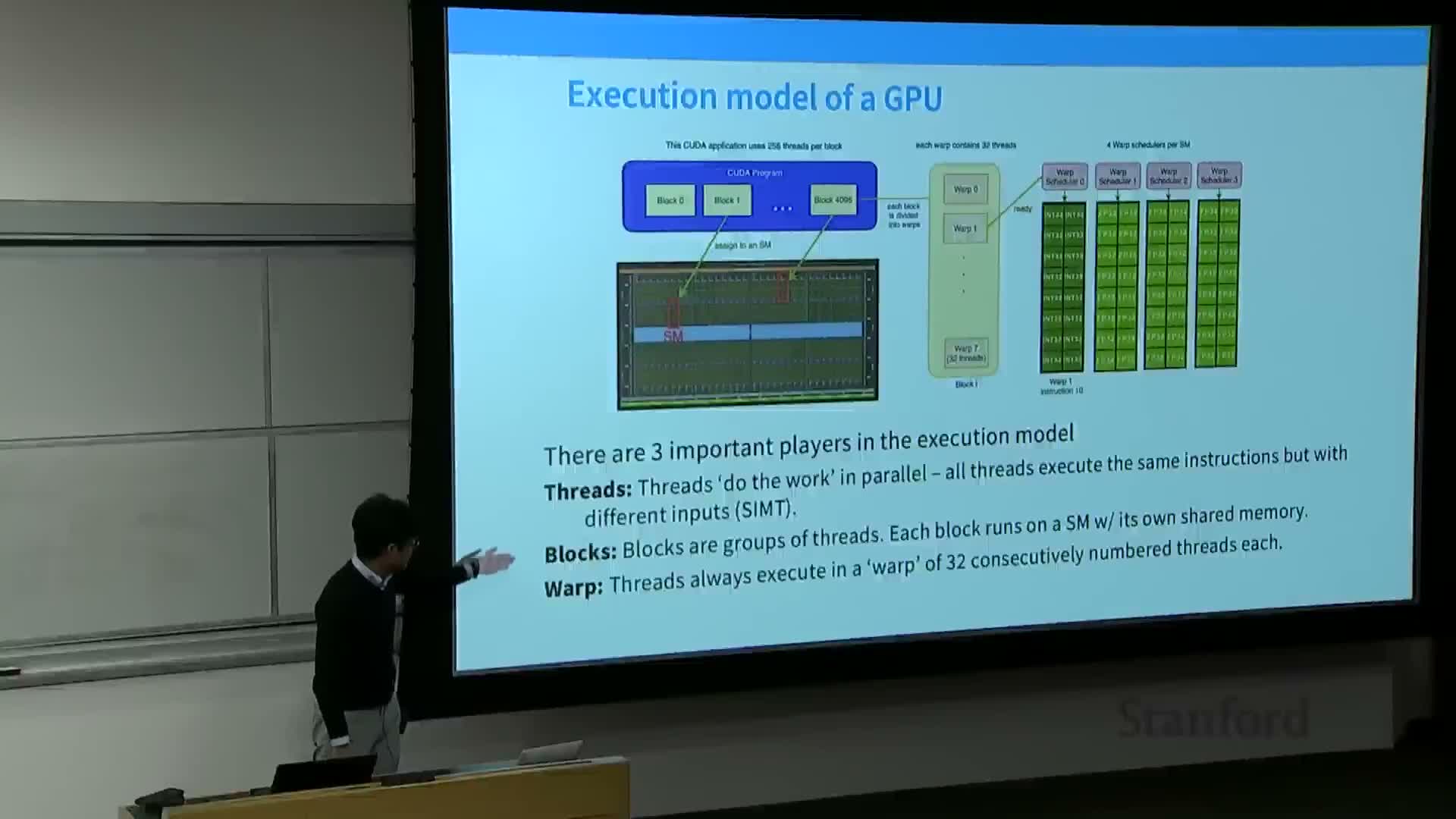

GPU execution granularity: blocks, warps and threads

GPU execution organizes work into blocks, warps, and threads — understanding this mapping is critical for high utilization.

-

Block: the unit scheduled onto an SM; contains many threads and can use shared memory visible to the block.

-

Warp: typically 32 threads that execute the same instruction in lockstep (SIMT).

-

Thread: the smallest program unit, with private registers.

Key points:

- A block is assigned to a single SM and is executed in warps.

- All threads in a warp must follow the same instruction stream; divergence penalizes utilization.

- Kernel design must consider mapping from blocks → SMs and threads → warps to achieve memory coalescing and high occupancy.

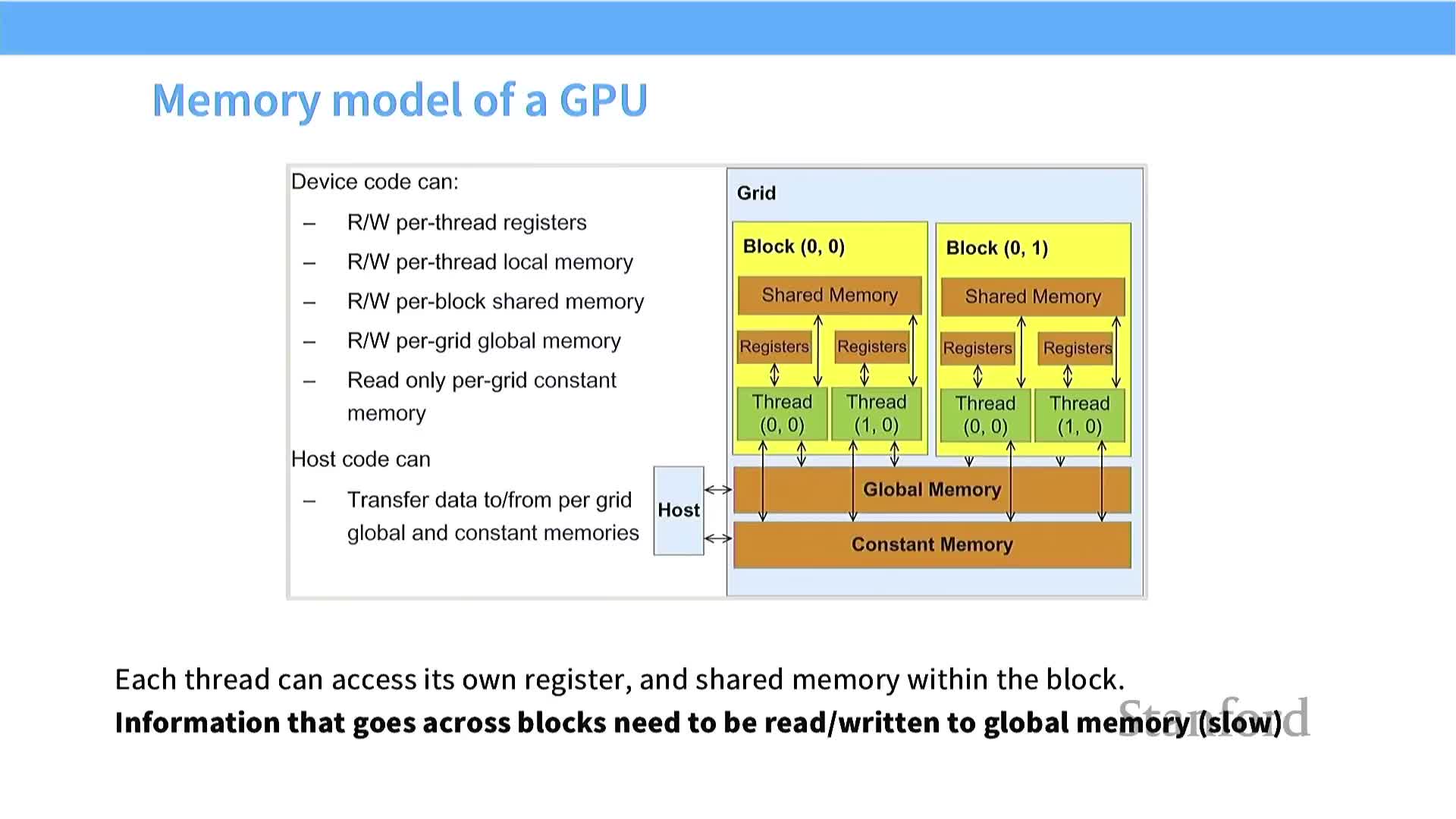

Logical memory model: registers, shared, and global memory

The GPU programming model exposes a hierarchy of logical memories — use each level for its intended purpose.

-

Per-thread registers: fastest storage; hold frequently used scalar and temporary values.

-

Per-block shared memory: programmable on-SM scratchpad for collaborative reuse across threads in a block.

-

Global memory: high-latency, visible across blocks; used for large data and inter-block communication.

Kernel design rules:

- Keep hot working sets in registers / shared memory.

- Minimize global memory reads/writes and use it mainly for large persistent storage or cross-block communication.

- Structure kernels to exploit on-SM storage for reuse and locality.

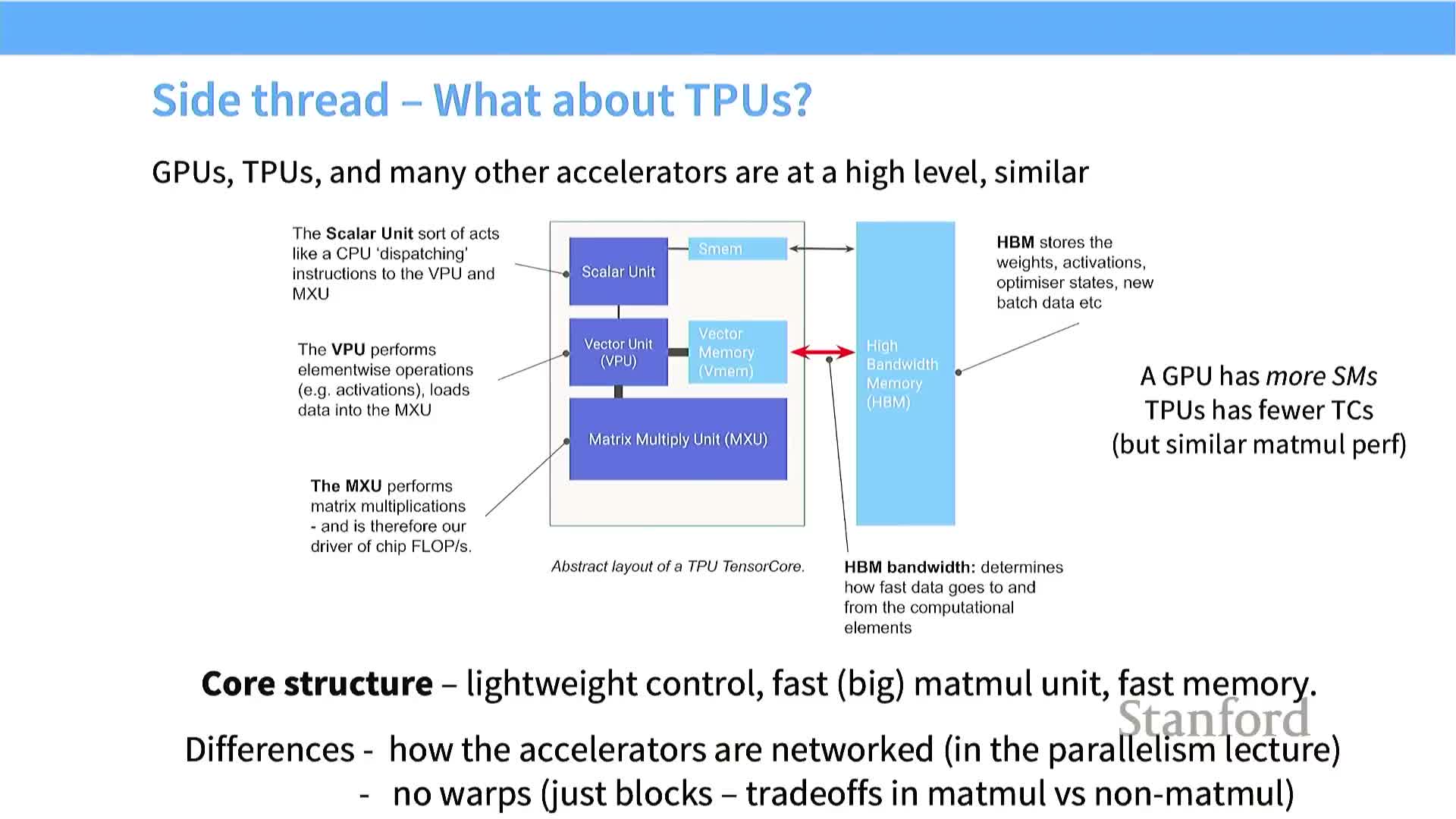

TPU architecture is conceptually similar to GPUs with MXU specialization

TPUs share several high-level concepts with GPUs but emphasize specialized matrix hardware.

- Commonalities:

- Many local compute units, on-chip fast memory, and external high-bandwidth memory.

- Importance of data locality and tiling strategies.

- Many local compute units, on-chip fast memory, and external high-bandwidth memory.

- Distinctive TPU features:

- Large, highly-optimized matrix multiply unit (MXU) for batched matrix multiplies.

- Scalar/vector units for control and element-wise ops, plus specialized on-core memory for tensor operands and accumulators.

- Large, highly-optimized matrix multiply unit (MXU) for batched matrix multiplies.

Practical takeaway: many GPU optimization patterns (tiling, data locality, memory-hierarchy awareness) carry over to TPU programming, though interconnect and multi-chip parallelism differ and must be handled separately.

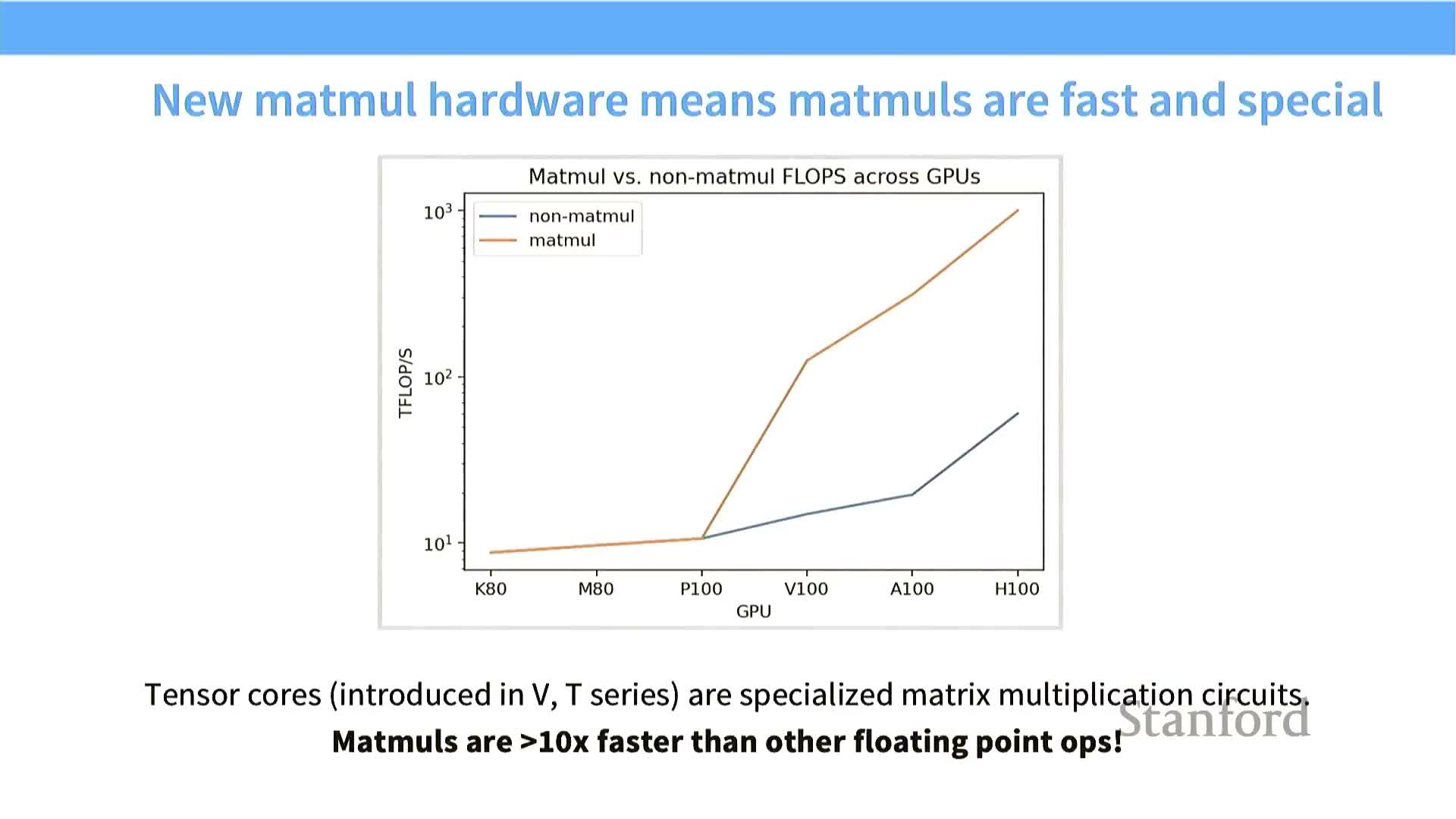

Matrix multiplies and tensor cores drive GPU value for ML

Modern accelerators became dominant because matrix multiply throughput outpaced general-purpose FLOPS growth, especially after adding specialized hardware like tensor cores.

-

Tensor cores provide very high-throughput mixed-precision matrix multiplication primitives.

- These units deliver orders-of-magnitude higher MAP (matrix arithmetic) FLOPS for matrix operations compared to scalar/non-matrix ops.

- Result: neural architectures and kernels are designed to make the bulk of computation MAP-friendly to exploit hardware specialization and achieve superior end-to-end performance.

Compute has outpaced memory growth, making memory movement the bottleneck

External memory bandwidth (host interconnects and device global memory) has grown much more slowly than raw compute capacity, creating a compute-versus-memory imbalance.

- Many GPUs are now compute-rich but memory-starved.

- End-to-end performance is increasingly determined by how efficiently an algorithm moves data between DRAM and on-chip buffers, not just raw FLOPS.

- Designing hardware-efficient algorithms therefore focuses on minimizing global memory traffic and maximizing reuse in fast on-chip storage.

Summary of GPU characteristics to guide optimization

Key GPU facts and the recurring optimization goals they imply:

-

Massively parallel SIMT execution — exploits regular, lockstep work across many threads.

-

SM-local fast memory vs. slower global memory — locality and proximity drive performance.

-

Hardware preference for matrix multiplies — matrix-friendly code maps best to peak throughput.

Repeated optimization checklist:

- Avoid branch divergence.

- Maximize data locality in shared memory and registers.

- Optimize memory access patterns (coalescing and alignment).

- Structure work to match SM and warp granularities.

Keeping these characteristics in mind provides a consistent toolkit for improving GPU kernel performance.

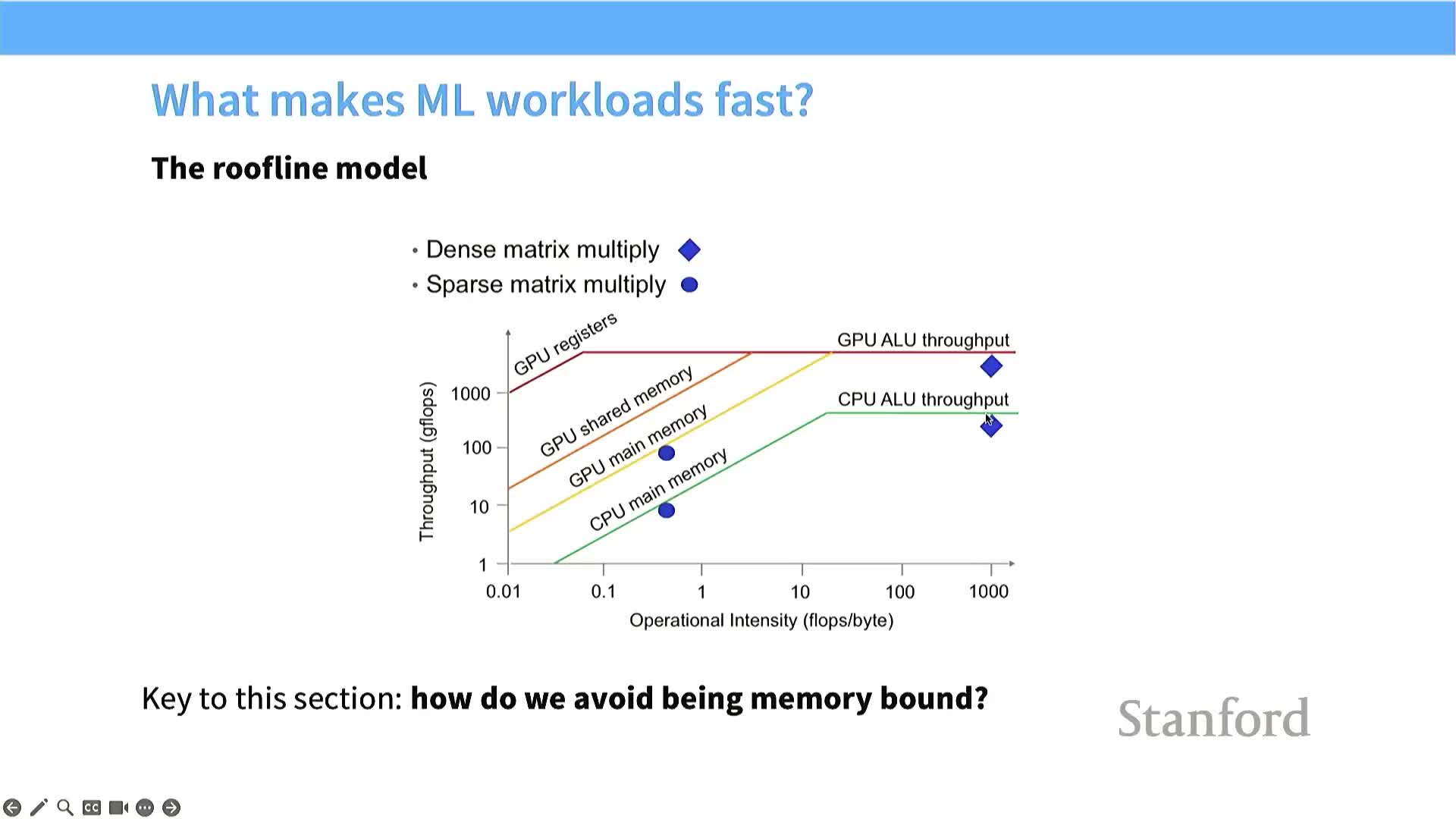

Roofline model explains memory- vs compute-bound regimes

The roofline model partitions performance into memory-bound and compute-bound regimes using arithmetic intensity (FLOPS per byte).

- Low arithmetic intensity or small problems → memory-bound: performance limited by global memory bandwidth (diagonal slope on the roofline).

- High arithmetic intensity and large problems → compute-bound: kernel can saturate compute and operate at the flat peak of the roofline.

Practical implication: increase arithmetic intensity (for example, via tiling, fusion, or lower-precision storage) to move kernels from the memory-limited to the compute-limited regime and unlock higher throughput.

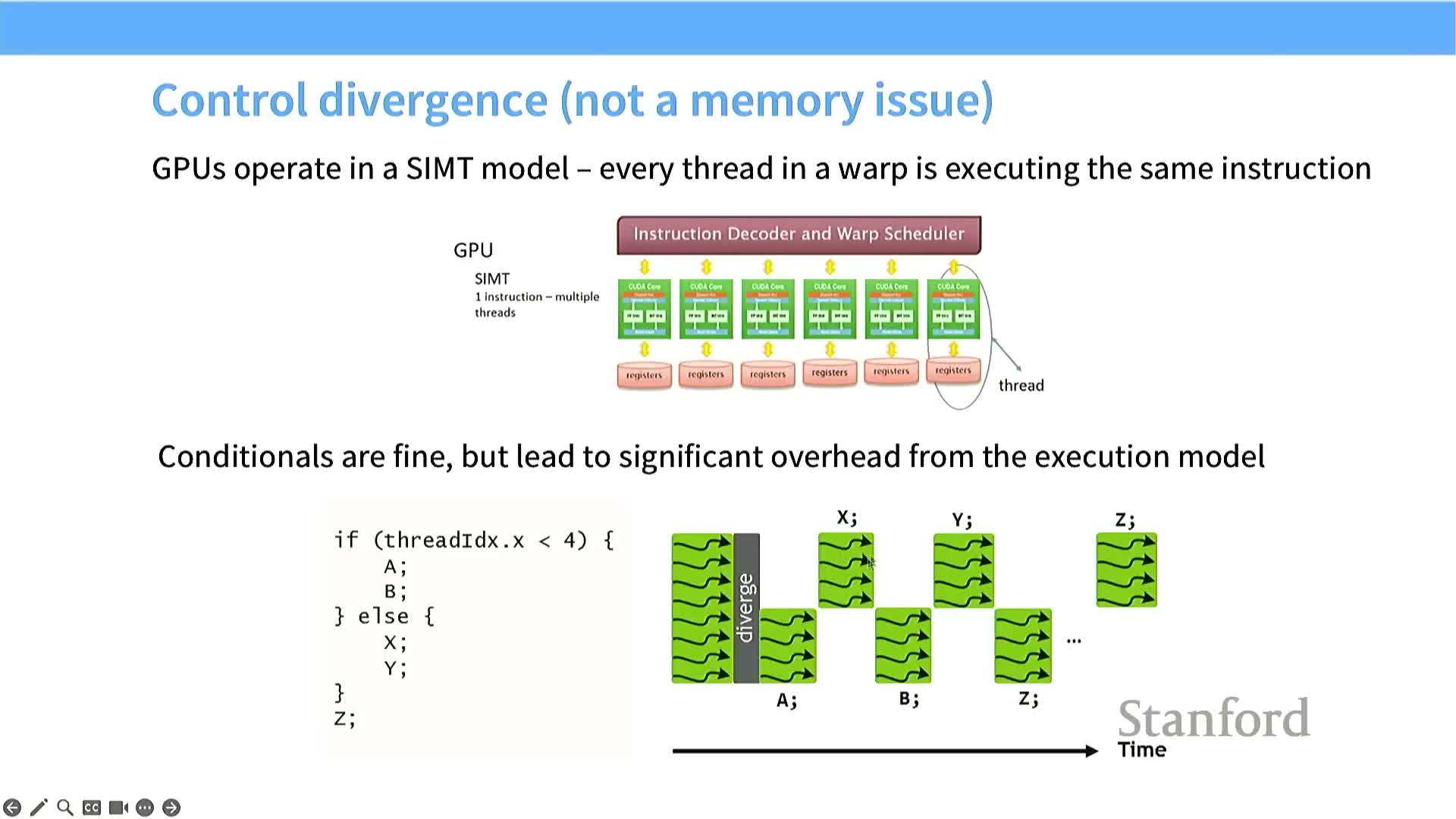

Warp divergence from conditionals degrades throughput

Warps execute the same instruction; divergent branches inside a warp serialize execution and reduce effective parallelism.

- If threads in a warp take different control paths, the GPU runs each branch path in turn while masking inactive threads.

- Divergence causes utilization and throughput to drop dramatically because only a subset of threads execute at a time.

Strategies to preserve SIMT efficiency:

- Avoid intra-warp control-flow divergence where possible.

- Structure workloads so divergent behavior is segregated across warps (e.g., group similar-control-flow threads together).

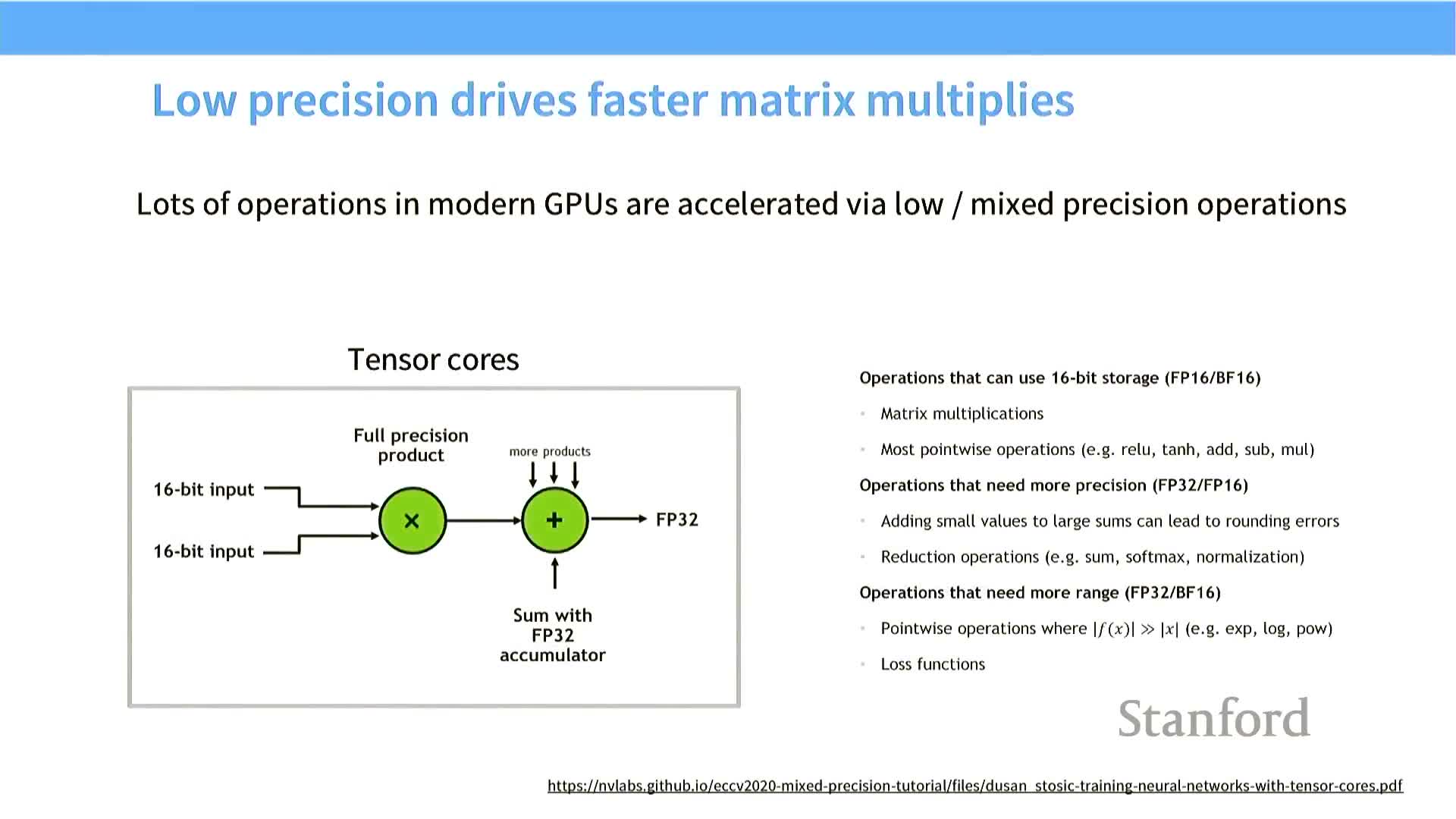

Lower-precision arithmetic increases effective memory bandwidth

Reducing numeric precision (FP32 → FP16/BF16 → INT8) provides substantial bandwidth and capacity benefits when done carefully.

- Lower precision reduces per-value storage and transfer costs, effectively multiplying usable memory bandwidth and on-chip cache capacity.

-

Mixed-precision commonly stores matrix inputs in low precision while keeping accumulators in higher precision (FP32) to preserve numerical stability.

- Special care is required for operations with high dynamic range or sensitivity to rounding.

When memory is the bottleneck, moving to lower-precision representations often yields large throughput gains with modest algorithmic changes and careful numerical engineering.

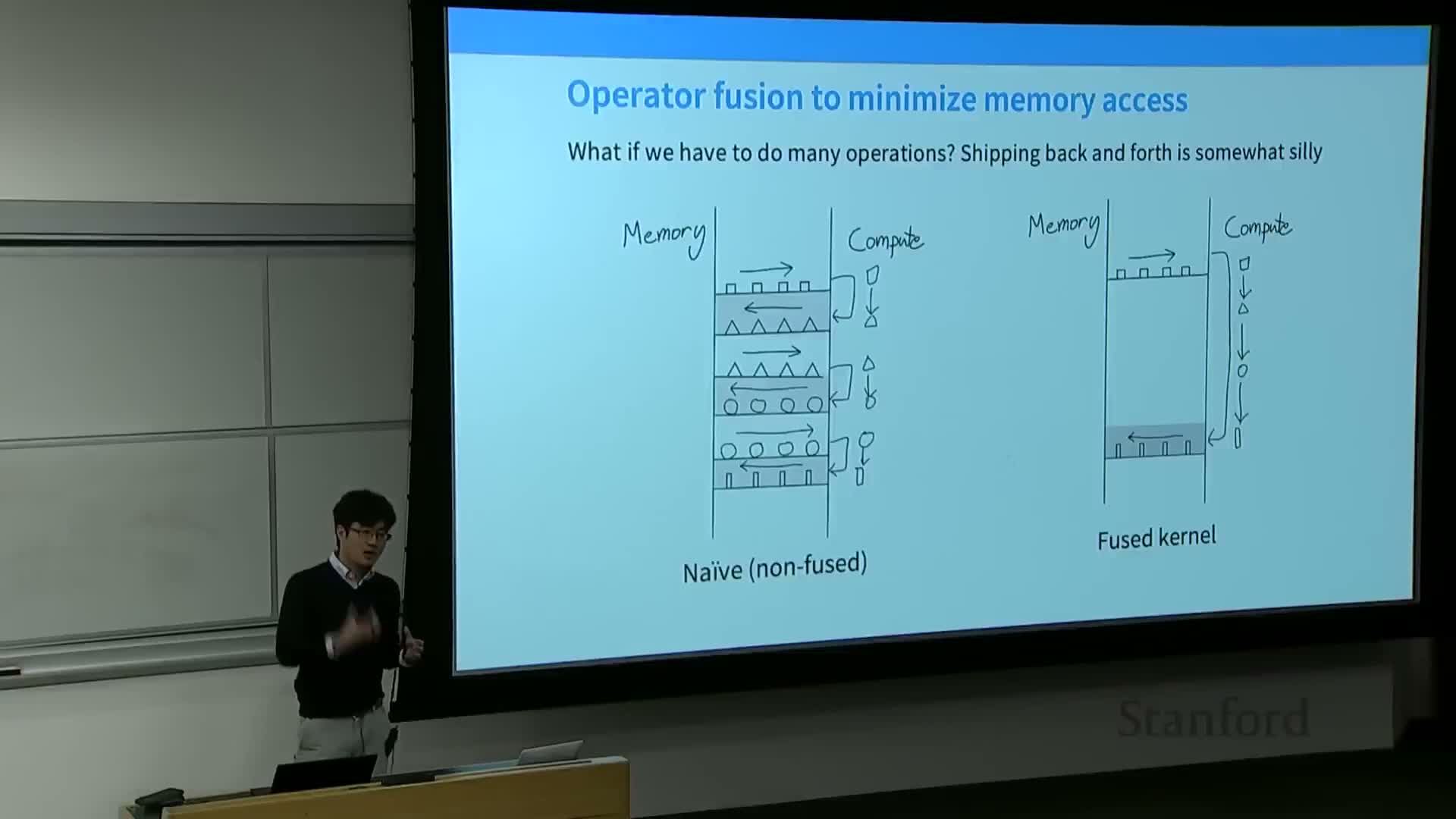

Operator fusion reduces global memory traffic by composing kernels

Operator fusion combines multiple sequential small operations into a single kernel so data stays in registers or shared memory.

- Fusion eliminates intermediate writes to and reads from global memory, drastically reducing memory traffic and launch overhead for small operators.

- Compilers and frameworks (for example, torch.compile or fused CUDA kernels) can perform fusion automatically.

- Result: increased arithmetic intensity and improved end-to-end throughput for fused operator sequences.

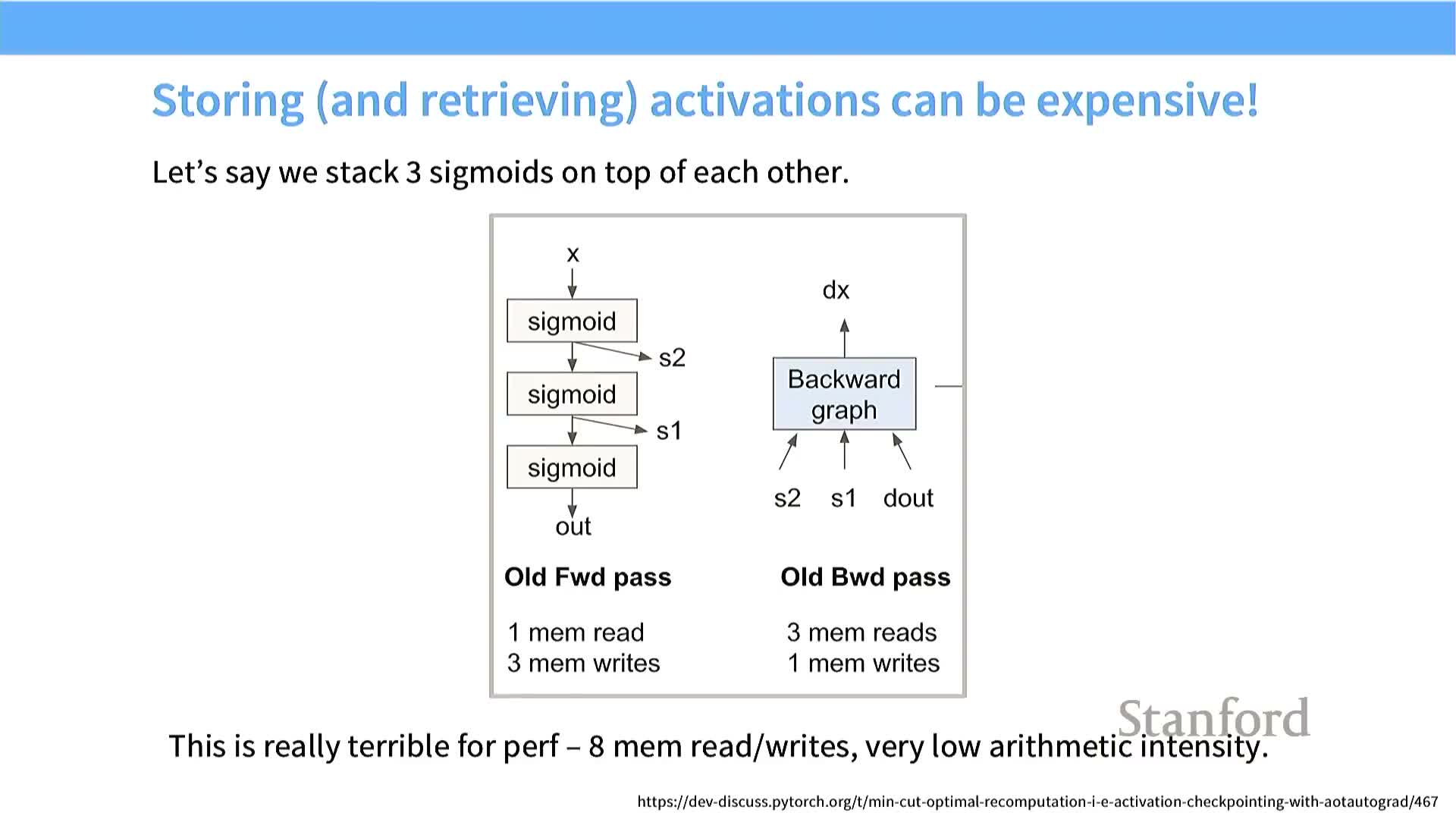

Recomputation trades compute for memory to reduce global accesses

Recomputation (checkpointing) trades extra FLOPS for reduced memory traffic by recomputing intermediates instead of storing them in global memory.

- Useful when a workload is memory-bound and compute-rich: use idle compute cycles to regenerate data that would otherwise require expensive DRAM reads.

- Trade-offs to consider:

- Wall-clock improvement depends on the relative cost of recompute FLOPS vs. DRAM access latency and bandwidth.

- Numerical determinism and reproducibility constraints.

- Memory footprint vs. recompute overhead balance.

Implementations must carefully choose which activations to checkpoint and which to recompute during the backward pass.

- Wall-clock improvement depends on the relative cost of recompute FLOPS vs. DRAM access latency and bandwidth.

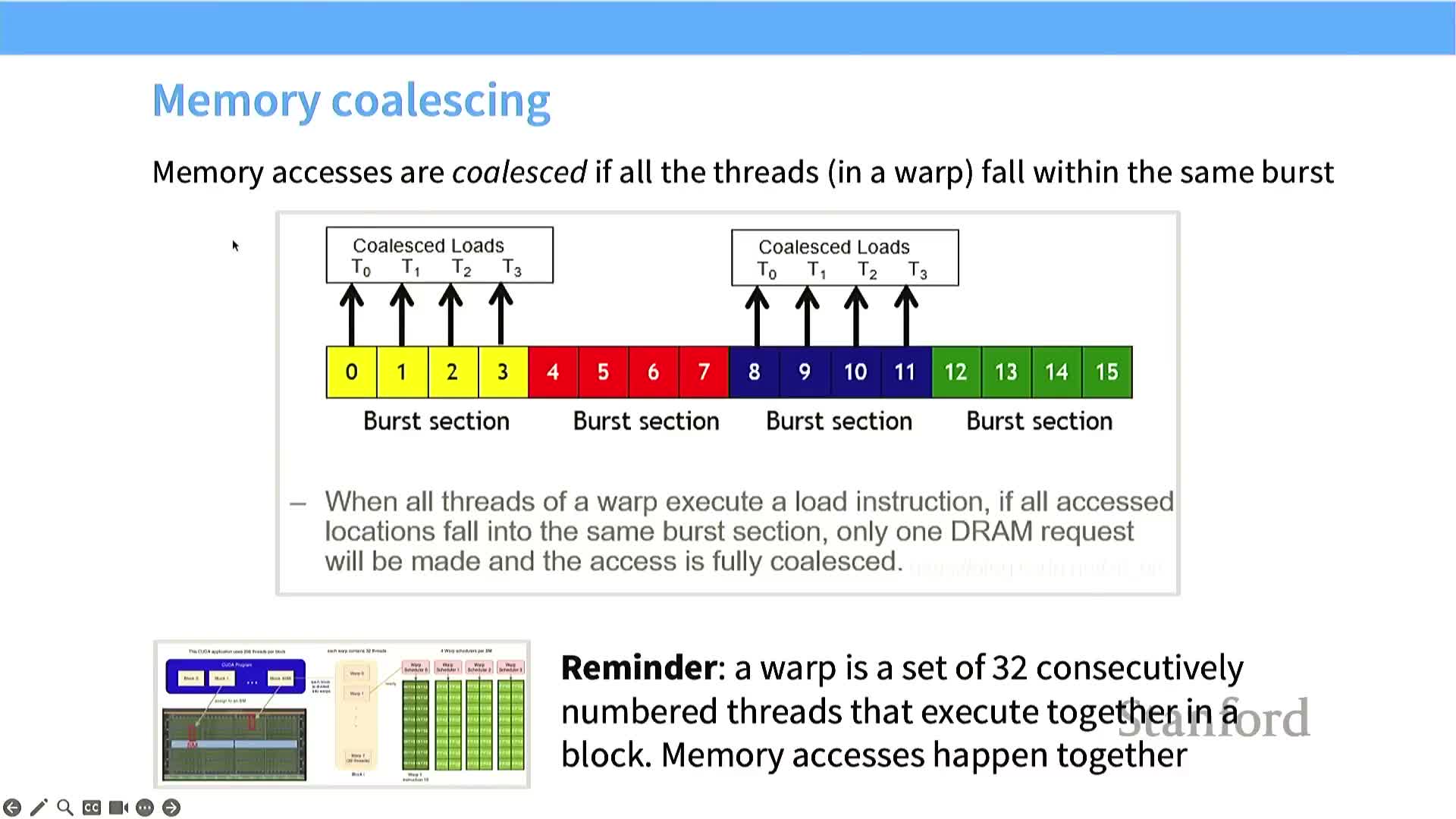

DRAM burst transfers and memory coalescing shape effective bandwidth

DRAM returns contiguous bursts of data per access; GPUs exploit this via coalesced memory accesses.

- A single DRAM access typically fetches a contiguous burst section, bringing neighboring addresses into an on-chip buffer.

- GPUs coalesce memory requests from threads in a warp so that nearby accesses combine into a single transfer, greatly amplifying throughput.

Kernel design implications:

- Layout arrays and choose memory strides so warp threads request nearby addresses (match row-major vs column-major to access pattern).

- Proper alignment and stride choices maximize coalescing and eliminate superfluous DRAM transactions.

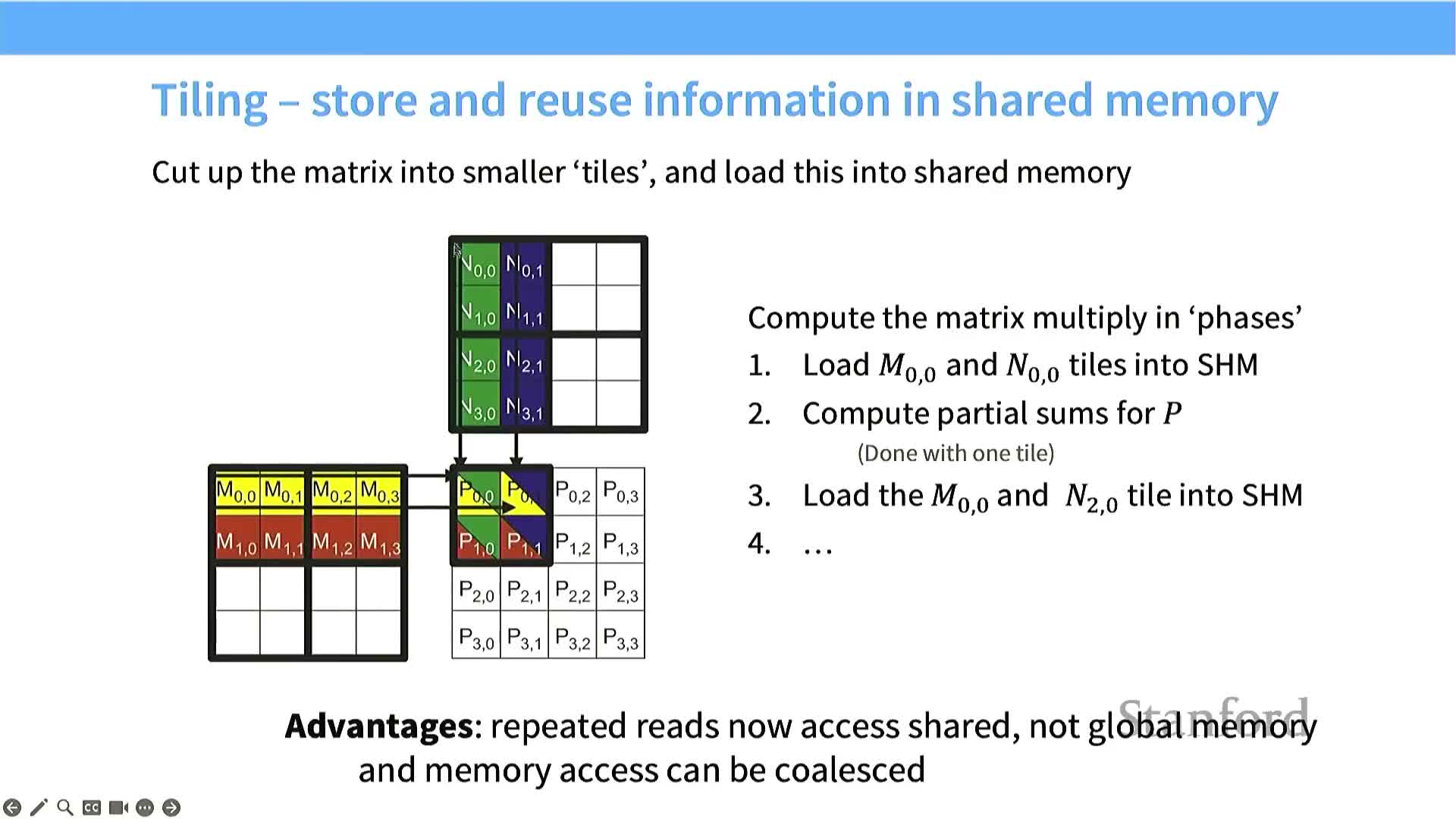

Tiling reuses on-chip memory to amortize global memory cost

Tiling partitions large matrix or tensor computations into small sub-blocks that fit into shared memory to maximize reuse.

- Load a tile from global memory into shared memory once.

- Reuse that tile for many FLOPS inside the SM.

- Write results back to DRAM once when finished.

Benefits and considerations:

- Tiling reduces global reads by a factor proportional to the tile dimension T, increasing arithmetic intensity.

- Effective tiling requires tuning tile sizes to shared memory capacity, ensuring coalesced loads, and matching tile shapes to the hardware’s preferred micro-tiles.

Tiling arithmetic: global reads scale with N/T and shared reads scale with T

For an N×N matrix multiply with tile size T, global memory loads per operand are reduced from O(N) per result to approximately O(N/T) per tile plus O(T) reuse inside shared memory.

- The total number of global memory reads is reduced by roughly a factor of T compared to the naive non-tiled algorithm (modulo tiling overhead and alignment constraints).

- This reduction in DRAM traffic is the primary reason tiled matrix multiplication dramatically increases arithmetic intensity and overall device utilization on modern GPUs.

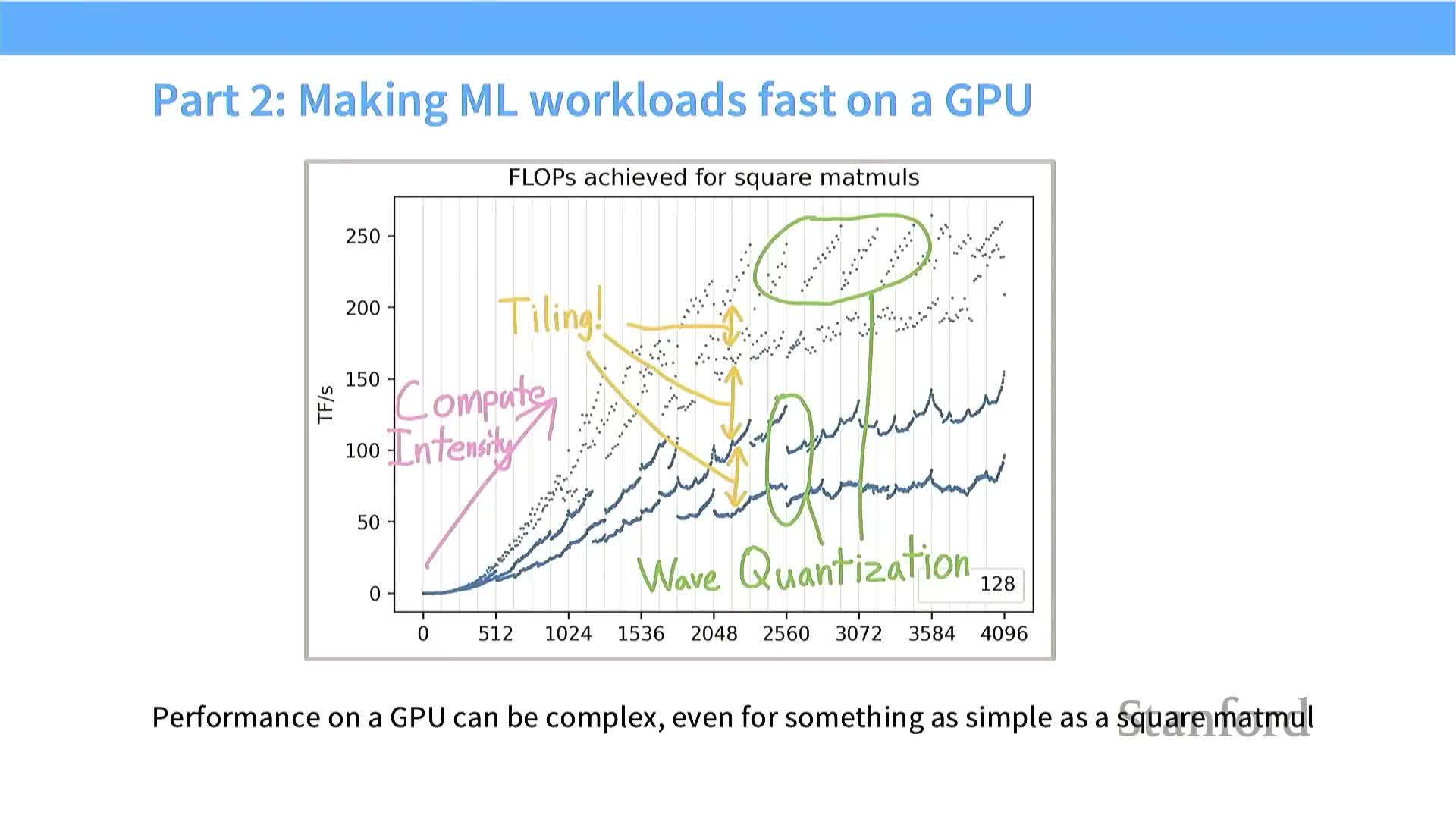

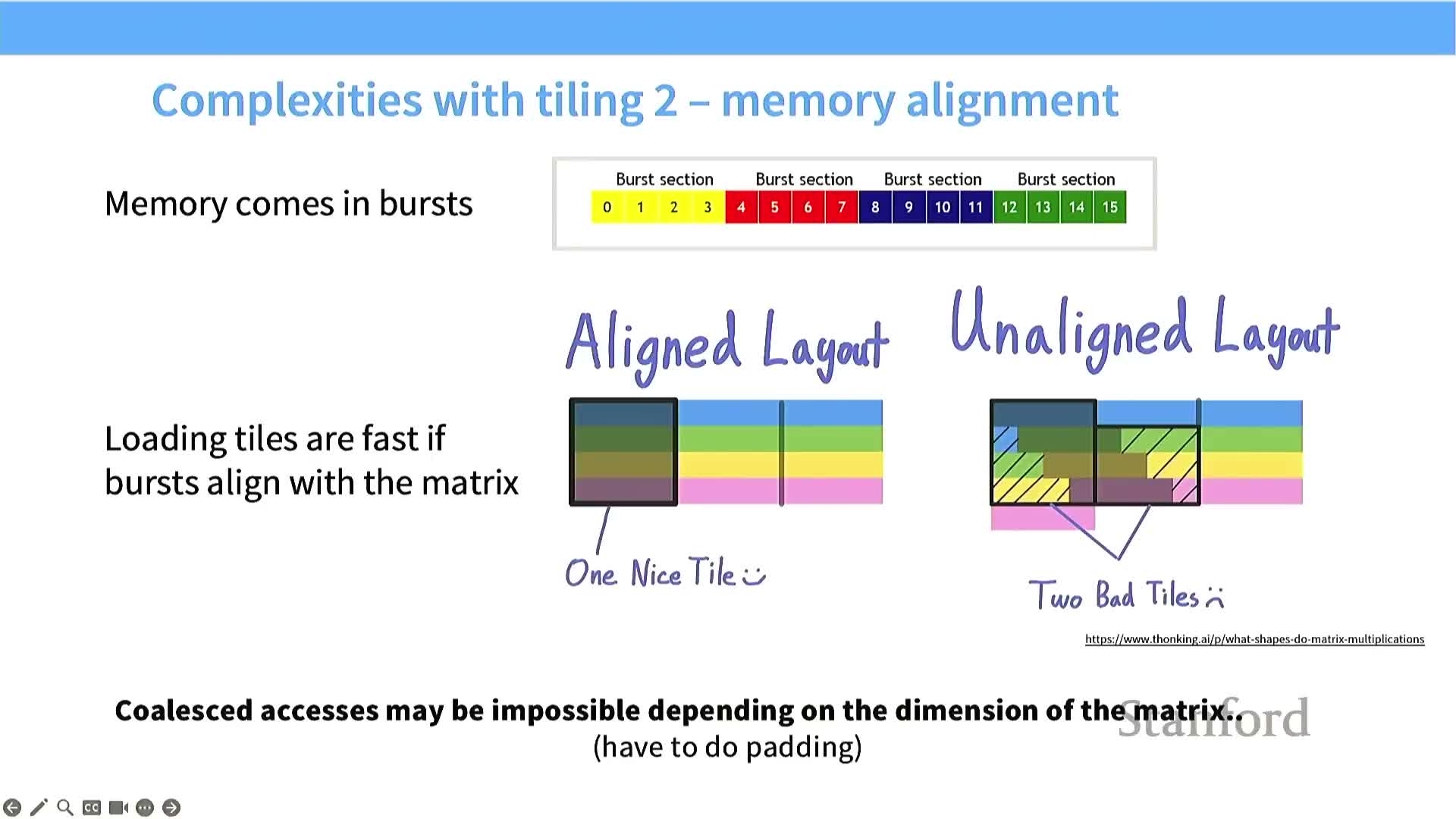

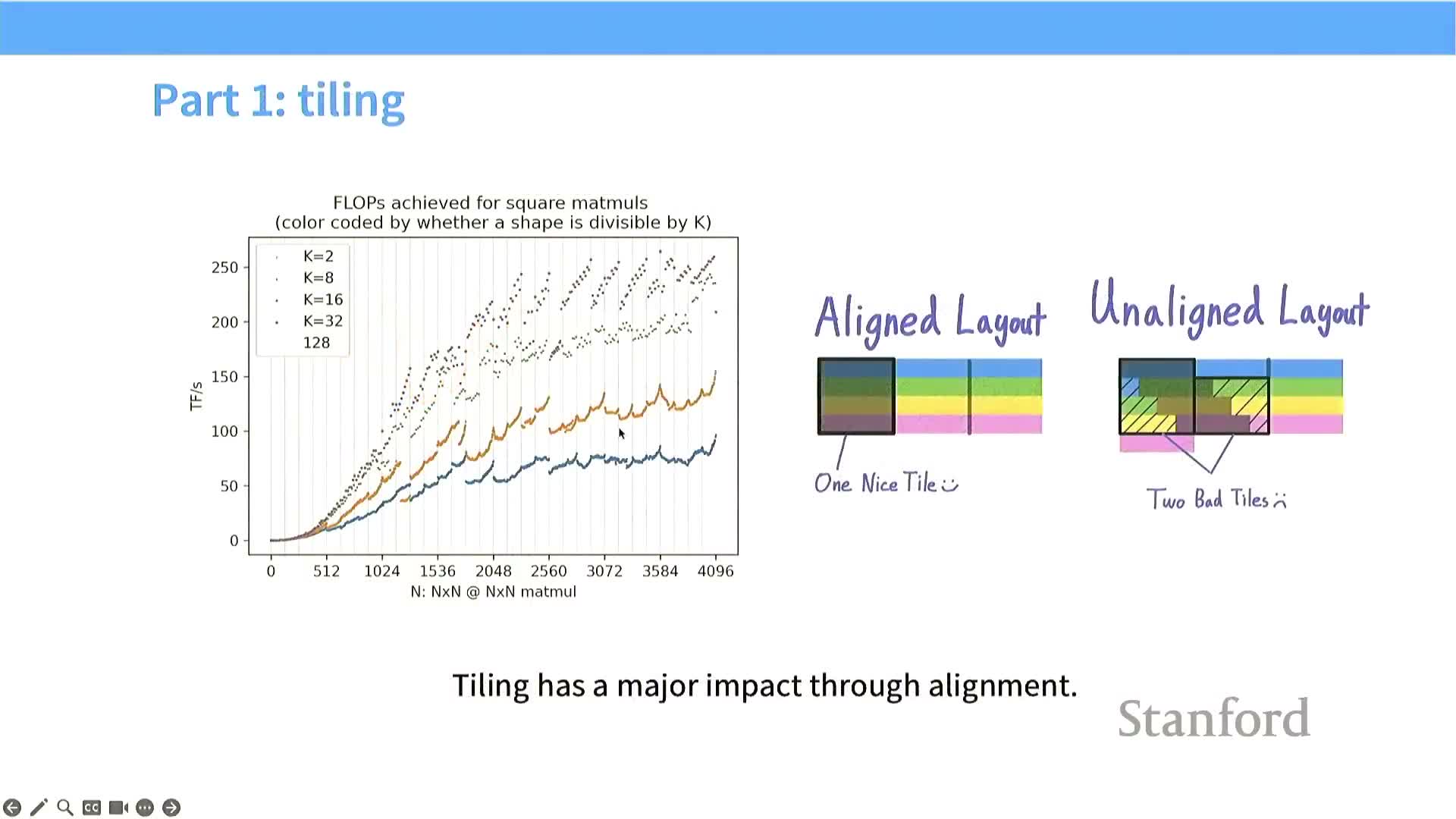

Tile-size discretization and alignment cause large throughput variance

Tile sizing, matrix dimension divisibility, and hardware granularities produce quantized performance behavior that must be managed.

-

Non-divisible dimensions create partially filled tiles that underutilize threads and SM resources.

-

Misaligned tiles can break DRAM burst coalescing and double memory transactions.

- These discretization effects produce wavelike performance curves as problem sizes change.

Mitigation strategies:

- Carefully select or pad dimensions to align with tile sizes, warp size, and burst alignment.

- Tune tile sizes to avoid pathological underutilization on typical problem sizes.

Wave quantization: tiles, SM count and occupancy create cliffs

The number of tiles (blocks) relative to the physical SM count yields occupancy quantization and wave-based dispatch behavior.

- If total tiles barely exceed or fall short of the SM count, work dispatch happens in waves, creating utilization cliffs.

- Small changes in matrix dimension can change the number of tiles from evenly mapping across SMs to leaving many SMs idle while a few execute leftover tiles, producing large throughput drops.

Avoidance techniques:

- Choose tile sizes and partitions that distribute work evenly across all SMs.

- Increase the number of independent blocks (more fine-grained partitioning) to smooth occupancy and avoid wave cliffs.

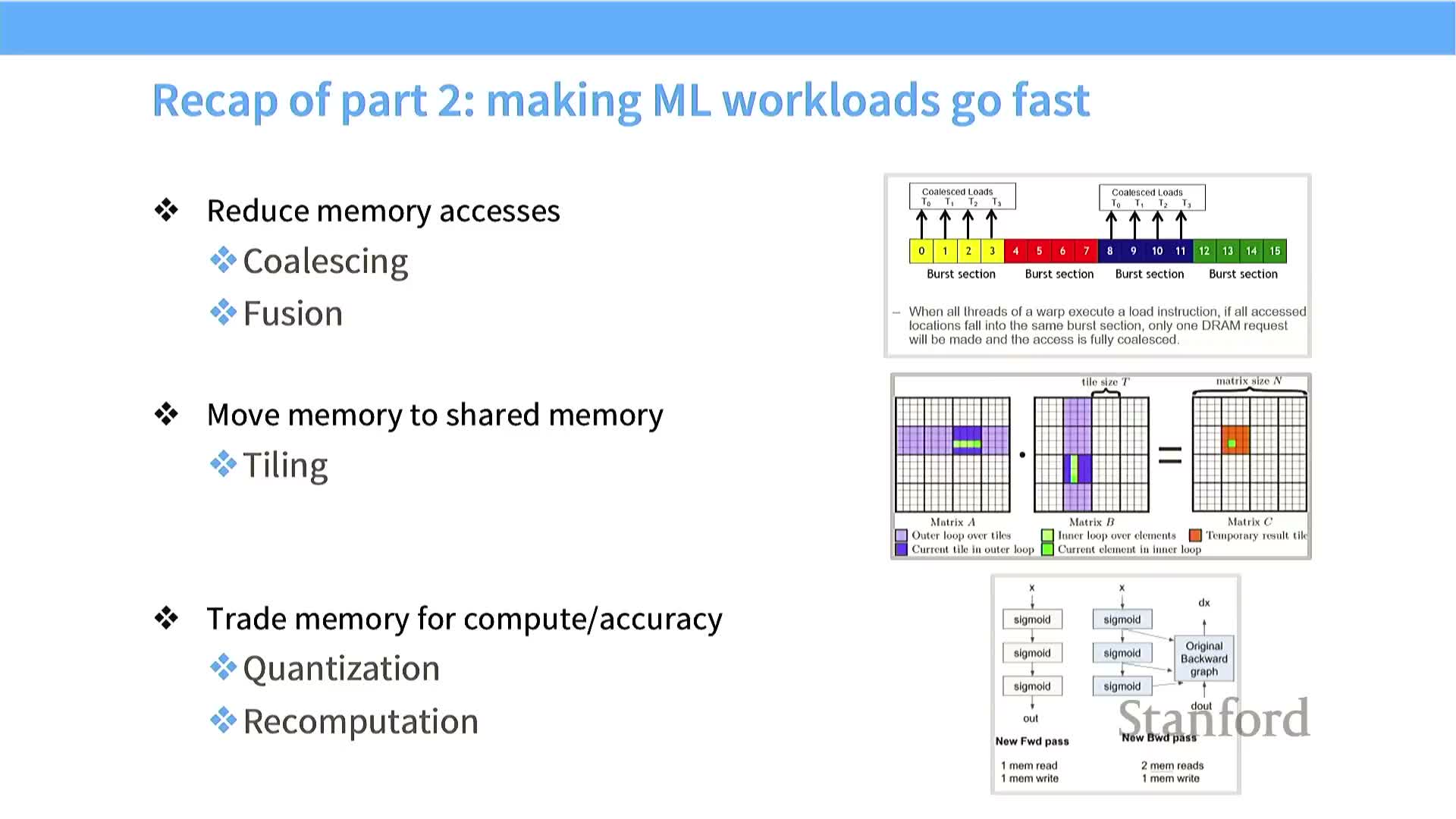

Practical optimization checklist for GPU kernels

Effective GPU optimization centers on minimizing global memory accesses and maximizing on-chip reuse via coalescing, fusion, and shared-memory tiling.

Key tactics:

- Design access patterns for burst-coalesced reads and proper alignment.

-

Fuse small operators into single kernels to avoid intermediate global writes.

-

Tile computations to fit shared memory and reuse loaded data for many FLOPS.

-

Trade compute for memory with recomputation/checkpointing when DRAM is the bottleneck.

- Choose numeric precision that balances bandwidth savings with numerical stability.

Collectively, these strategies increase arithmetic intensity and move kernels toward the compute-bound roofline.

Flash Attention uses tiling and recomputation to reduce HBM accesses for attention

Flash Attention implements attention with tiled matrix multiplies and an online softmax, enabling exact attention with sub-quadratic HBM accesses.

- Keeps as much intermediate data in shared memory as possible.

- Computes softmax normalization terms incrementally per tile (online), avoiding materializing large N×N matrices in global memory.

- Trades extra local computation and careful tiling for dramatically fewer global reads/writes, yielding large speedups for long-context transformer attention.

Attention computation is tiled but softmax is a global normalization challenge

Attention decomposes into three steps: compute QK^T, apply a row-wise softmax, then multiply by V — the softmax normalization is the algorithmic challenge for tiled execution.

- The KQ product can be tiled and accumulated across tiles.

- The row-wise softmax normalization requires the sum of exponentials per row — a global reduction if done naively.

- Materializing full N×N logits violates on-chip memory limits, so a tile-by-tile online algorithm that maintains per-row state is required to evaluate softmax without full-matrix storage.

Online softmax enables tile-by-tile softmax computation

The online softmax algorithm maintains a running maximum and a running sum of exponentials corrected for changes in the maximum as new elements arrive — enabling streaming, numerically stable normalization.

- For each incoming tile of logits the algorithm:

- Updates the running max for the row.

-

Rescales the running sum to account for any max change and adds the tile’s contributions.

- Updates the running max for the row.

- This telescoping/online formulation preserves numerical stability and computes the normalization factor from per-tile state, avoiding the need to store full N×N logits in global memory.

Flash Attention integrates tiled matmuls and recomputation for forward and backward passes

Flash Attention forward and backward mechanics combine tiling, online reduction, and recomputation to avoid N^2 storage while remaining exact.

Forward pass (high level):

- Tile Q and K, compute dot-product tiles and accumulate per-row logits.

- Update online softmax statistics per row tile (running max and sum).

- Apply normalized weights to V in tiled form — no N×N matrix is materialized in HBM.

Backward pass strategy:

- Use recomputation: re-evaluate tiles on the fly during gradient propagation instead of storing N^2 activations to global memory.

- Trade extra FLOPS for reduced DRAM traffic and memory footprint.

Combined effect: tiling, coalesced accesses, online reduction, selective low precision, and recomputation yield significant throughput and memory-efficiency improvements in Flash Attention implementations.

Final takeaway: optimize data movement first, then compute

Hardware trends make memory movement the dominant limiter for large models, so algorithm and implementation efforts should prioritize minimizing global memory traffic and maximizing on-chip reuse.

Practical toolkit for high performance:

- Lower precision when safe (mixed-precision).

- Fuse operators to avoid intermediate DRAM writes.

- Coalesce memory accesses and align buffers for bursts.

- Tile to exploit shared memory and increase reuse.

- Recompute activations selectively to trade FLOPS for reduced DRAM access.

Applied systematically, these techniques raise arithmetic intensity, move kernels toward compute-bound performance, and enable state-of-the-art primitives such as Flash Attention for scalable transformer training and inference.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: