CS336 Lecture 8 - Parallelism - Part 2

- Multi-GPU training requires structuring computation to minimize inter-device data transfer.

- Lecture content is organized into two parts: collective operations implementation and distributed training strategies with benchmarking and code examples.

- Collective operations provide standardized multi-device primitives such as broadcast, scatter, gather, reduce, all-gather, and reduce-scatter for coordinating distributed computation.

- GPU system topologies form a hierarchy (SM L1, HBM, PCIe, NVLink, NVSwitch) and influence where and how collective communication is executed.

- Topology-discovery tools reveal inter-GPU links such as NVLink and show how network cards and PCIe paths connect GPUs and CPUs, which affects communication strategies.

- NCCL (NVIDIA Collective Communications Library) implements low-level GPU-aware collectives and torch.distributed provides a higher-level, multi-backend interface for Python workloads.

- Distributed processes must initialize a process group and use synchronization primitives like barrier to coordinate multi-process execution.

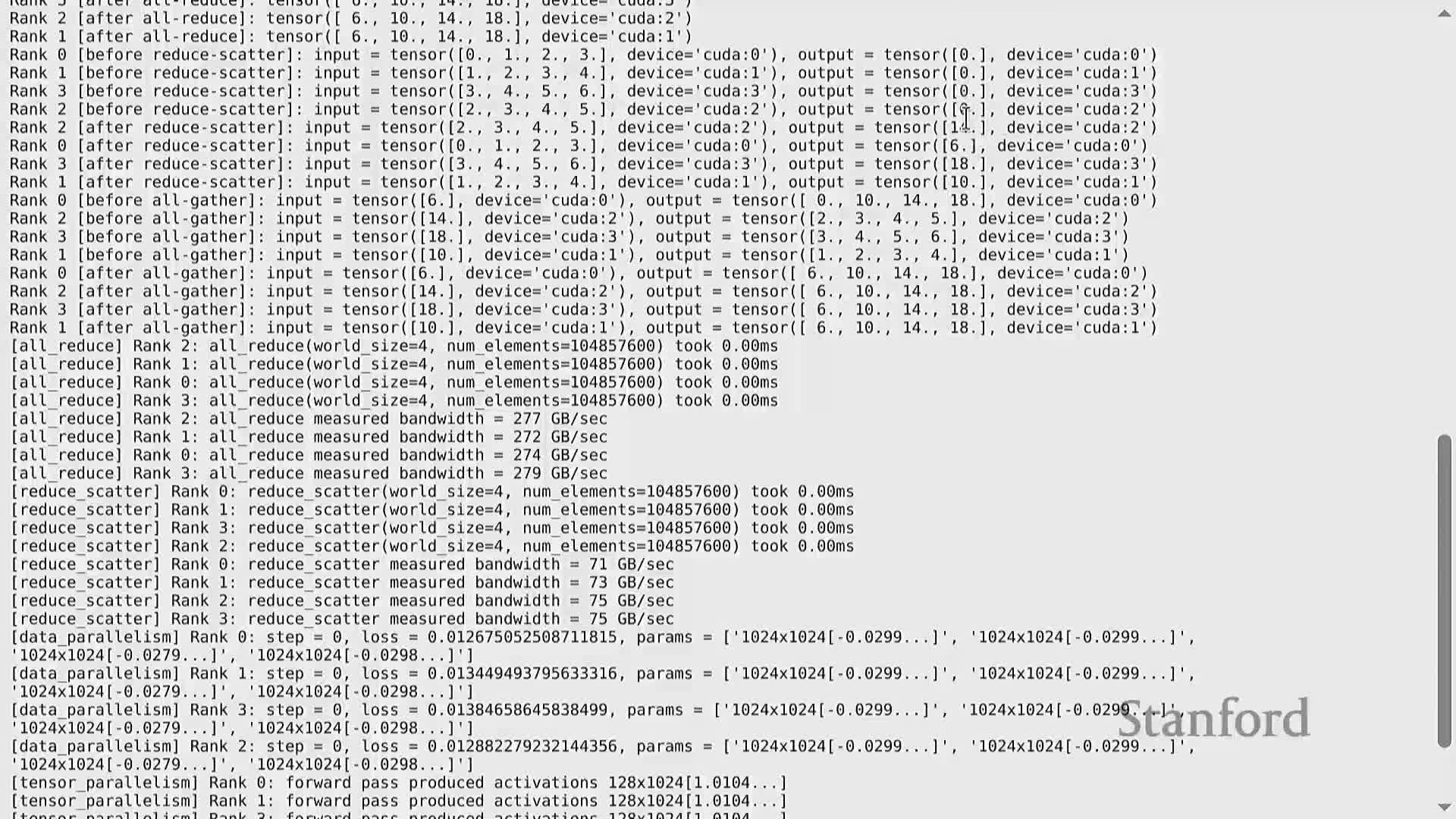

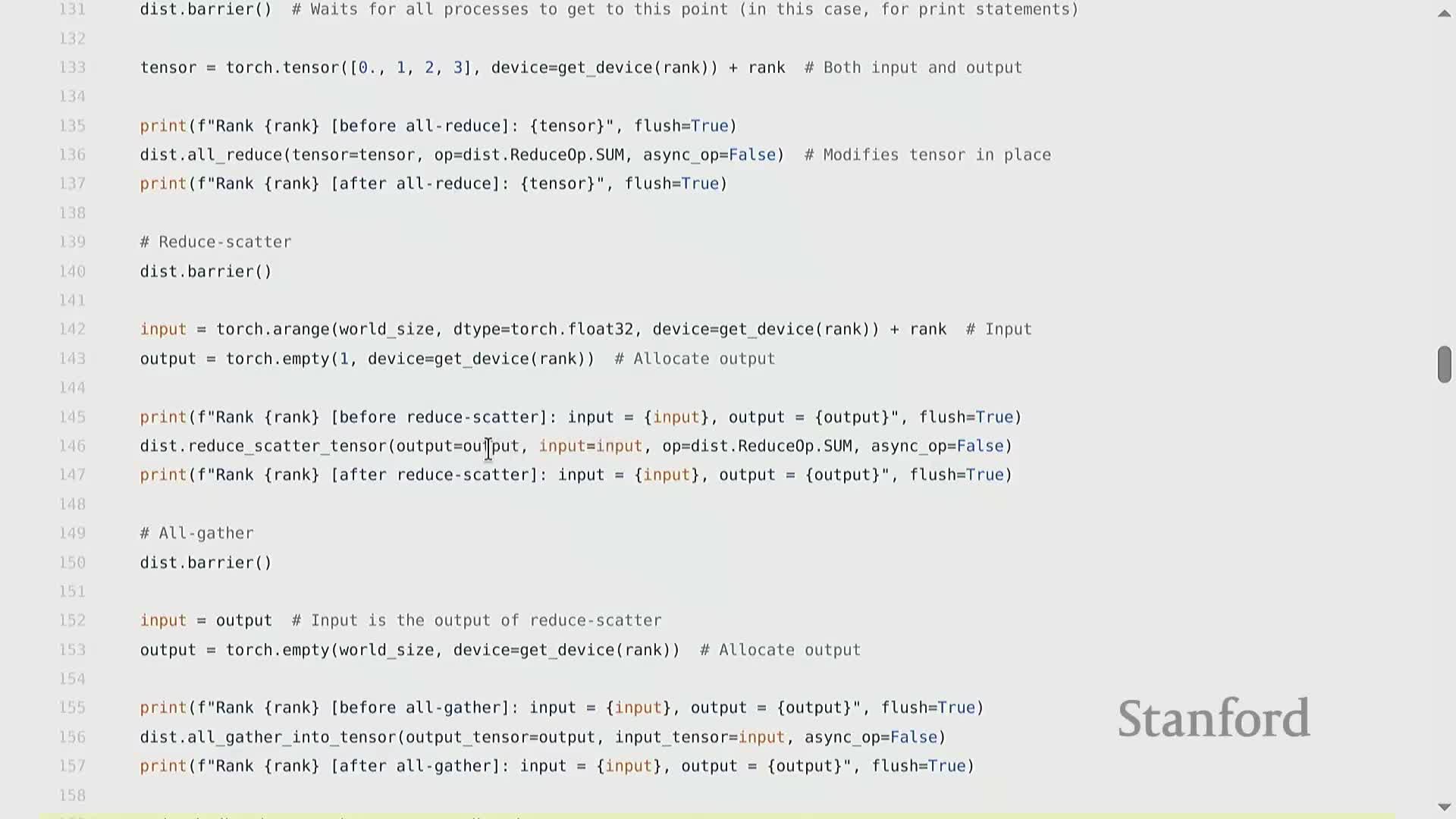

- All-reduce aggregates values across ranks using an associative operation and places the same reduced result on every participating rank, typically in-place on the input tensor.

- Reduce-scatter computes a reduction across ranks and distributes disjoint portions of the reduced tensor to different ranks, producing a smaller local output per rank.

- All-gather concatenates tensors from all ranks so that each rank ends up with the full collection, and when paired with reduce-scatter it composes to an all-reduce.

- Collective operations require consistent tensor shapes across ranks and a convention for which tensor dimension maps to devices in sharded operations.

- Reliable benchmarking of collectives requires warm-up, synchronization, and precise byte accounting to compute effective bandwidth.

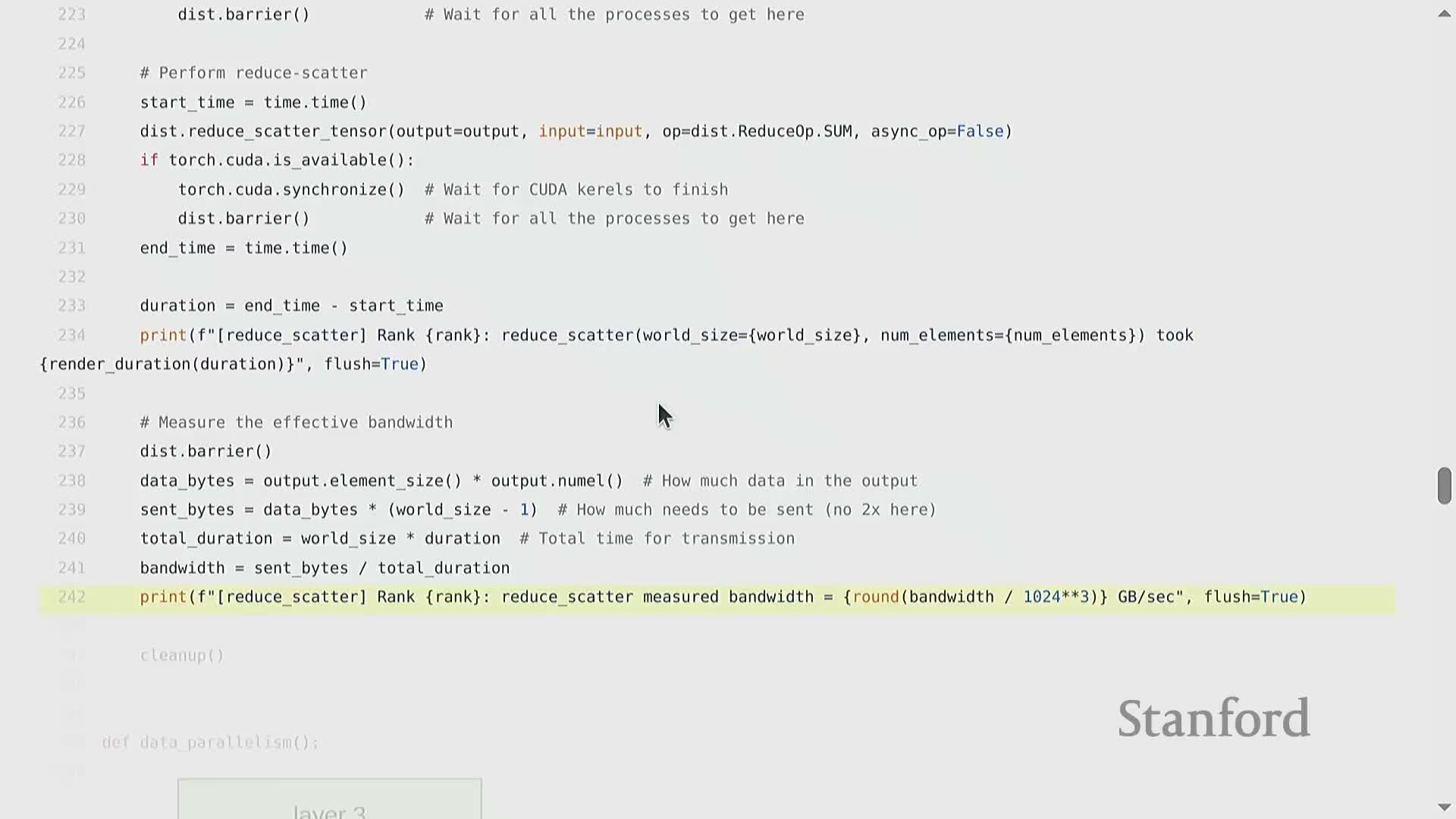

- Reduce-scatter benchmarks follow the same methodological steps as all-reduce but typically report different effective bandwidth due to different traffic patterns and less broadcast traffic.

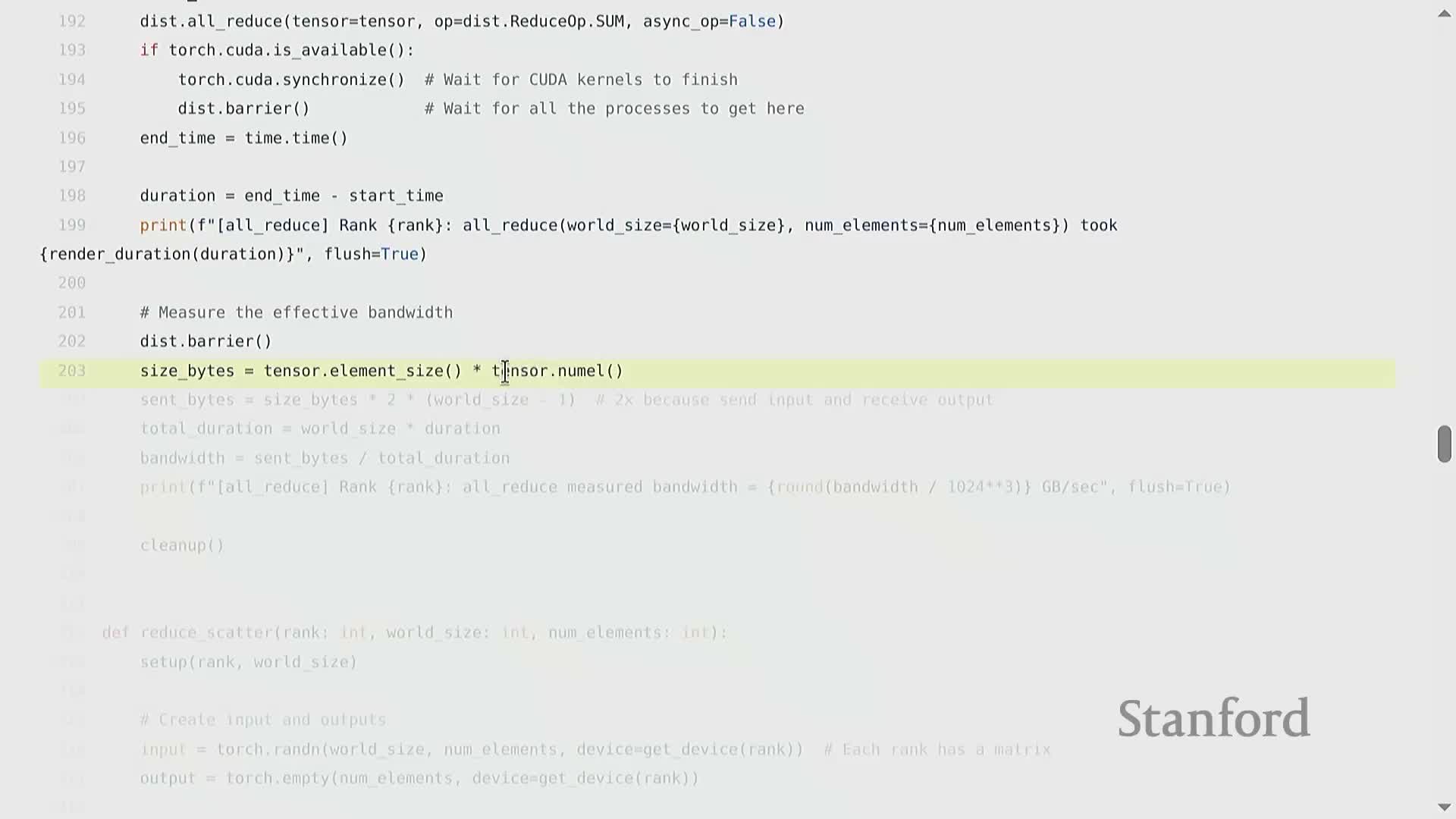

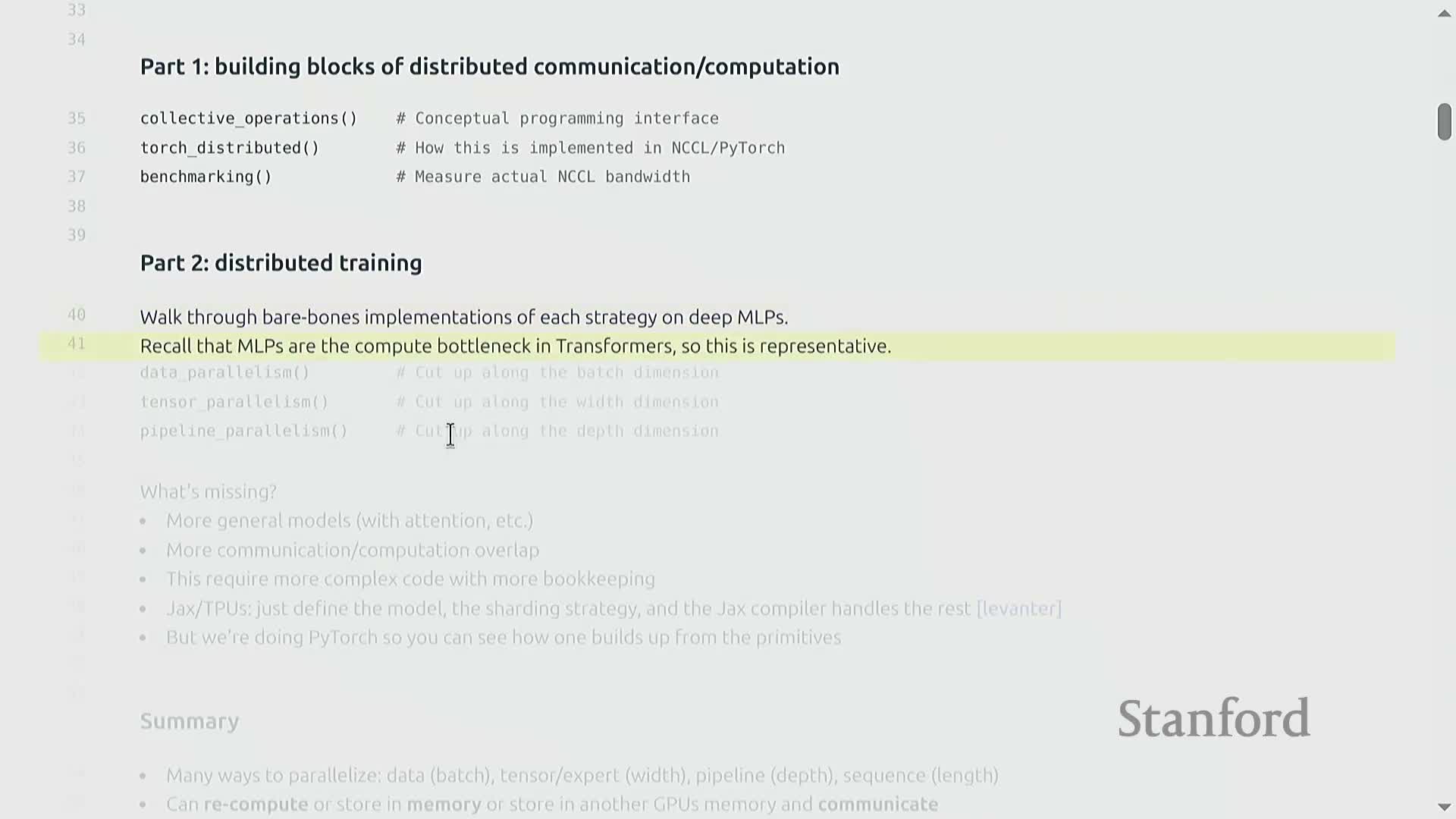

- Distributed training strategies (data, tensor, pipeline) can be understood by applying them to a deep MLP as a representative compute-bound workload.

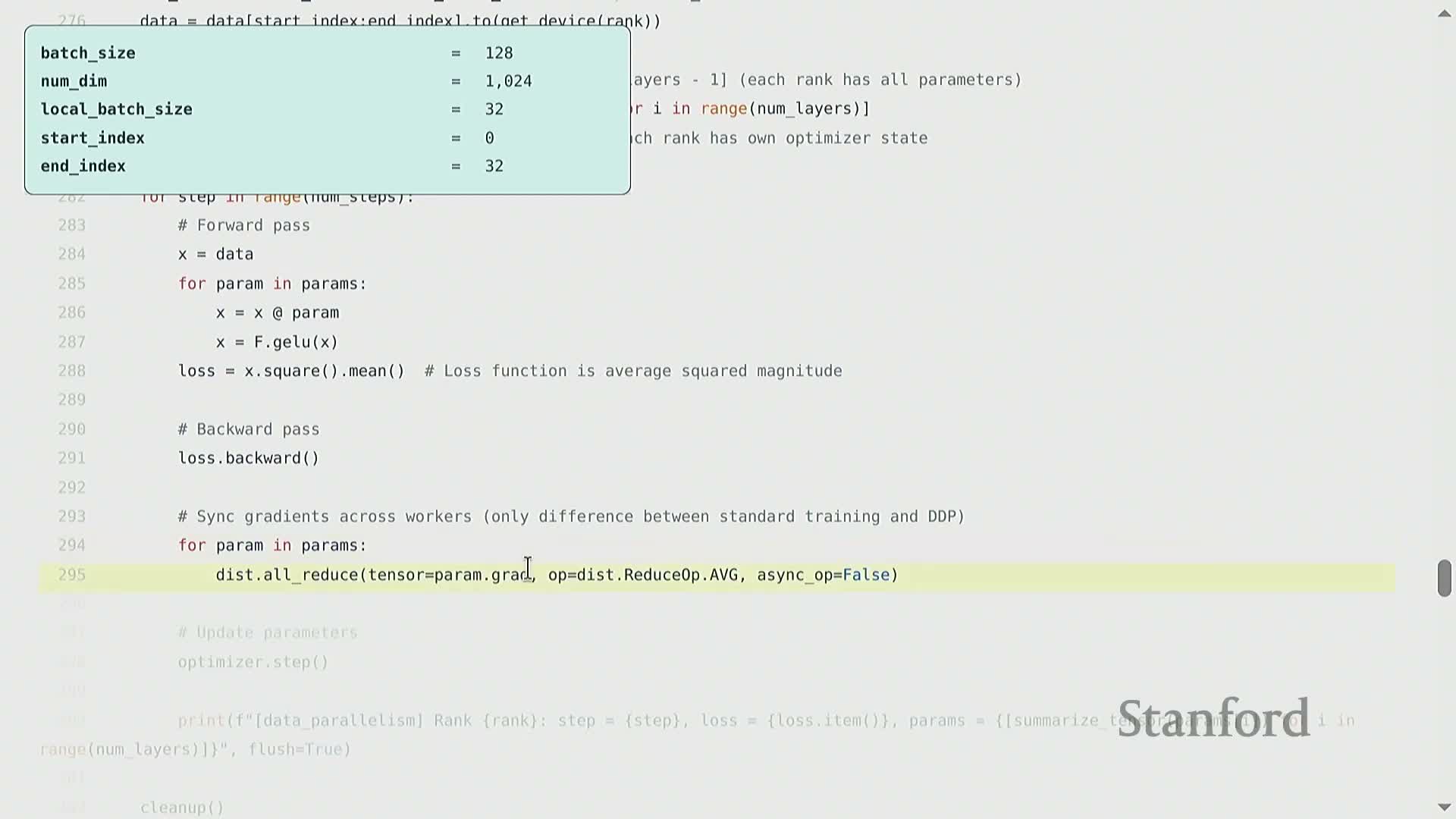

- Data-parallel (DDP) training replicates the model on each device, partitions the batch across ranks, and synchronizes gradients via all-reduce after the backward pass.

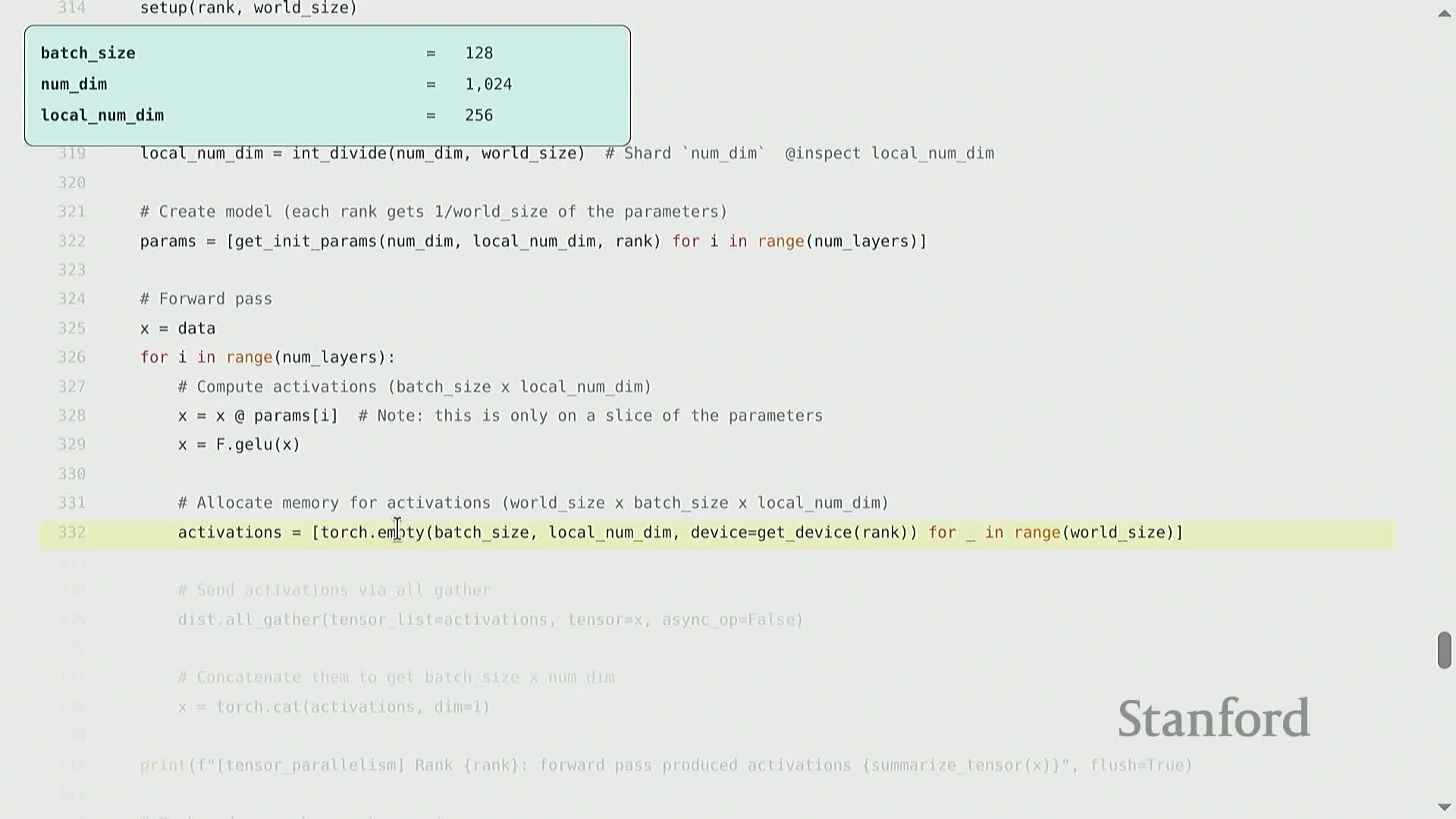

- Tensor parallelism shards parameter matrices (for example across the hidden dimension), computes local partial activations, and uses all-gather to assemble full activations for subsequent layers.

- Pipeline parallelism partitions layers across devices and streams microbatches through the partitioned model using point-to-point sends and receives to improve utilization.

- Overlapping communication and computation via asynchronous sends/receives and handles reduces stalls and improves GPU utilization in pipeline and other parallel schemes.

- Full pipeline training requires coordinating forwards and backwards across ranks, handling last-stage loss computation, and implementing backward-stage sends to propagate gradients upstream.

- High-level frameworks such as JAX expose sharding primitives so users can specify how tensor dimensions are partitioned and let the compiler generate the underlying communication and kernel launches.

- Parallelization choices trade off computation, communication, and memory; recomputation, checkpointing, and sharding are recurring techniques, and hardware evolution maintains a multi-level hierarchy of limits.

- Practical implementation questions include handling data-dependent state (batchnorm), using high-level libraries (FSDP), activation checkpointing APIs, specialized hardware trade-offs, incremental training, and how collectives are executed at runtime.

Multi-GPU training requires structuring computation to minimize inter-device data transfer.

Modern multi-GPU systems expose a multi-level memory and communication hierarchy where compute units (SMs) perform arithmetic that fetches inputs from different tiers:

- On-chip caches (e.g., L1) for the fastest, smallest accesses

- High-bandwidth on-device memory (HBM) for larger working sets

-

Remote device memory reached over interconnects (PCIe, NVLink, network) for the slowest accesses

Data transfers across these levels are orders of magnitude slower than on-chip arithmetic, so maximizing arithmetic intensity and avoiding unnecessary transfers is central to performance.

Common techniques to reduce memory traffic:

- Fusion: combine operations to eliminate intermediate writes/reads

- Tiling: work on local tiles in a scratchpad before committing results to slower tiers

When scaling across GPUs and nodes, model parameters and optimizer state are either replicated or sharded, and the chosen distribution determines communication volume and latency.

Design goal: keep data local as long as possible — this is the primary systems objective for efficient multi-GPU training.

Lecture content is organized into two parts: collective operations implementation and distributed training strategies with benchmarking and code examples.

The material is organized into two complementary parts:

- Building blocks — collective communication primitives and their low-level implementations

-

Higher-level distributed training strategies — data, tensor, and pipeline parallelism

Teaching approach:

- Emphasize concrete code examples so concepts map directly to implementation

- Use benchmarks to reveal performance effects of different designs

- Combine theory (primitives) with practice (real code) so students see both how and why performance differs

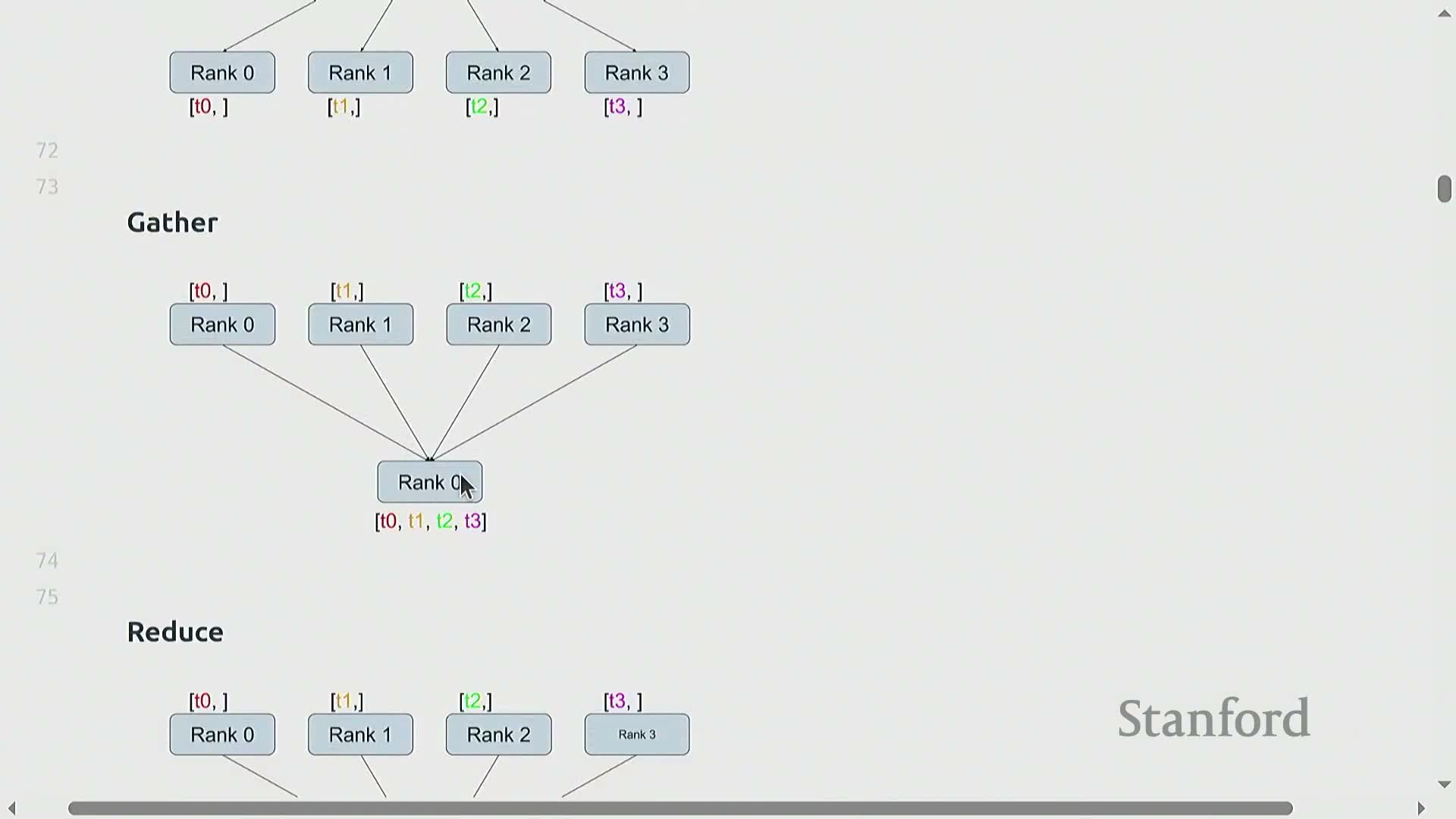

Collective operations provide standardized multi-device primitives such as broadcast, scatter, gather, reduce, all-gather, and reduce-scatter for coordinating distributed computation.

Collective operations are foundational primitives in parallel programming that hide point-to-point bookkeeping and provide efficient coordinated data movement across devices.

Core terms:

- World size: number of participating devices

-

Rank: device index within the group

Common collectives:

- Broadcast: copy a tensor from one rank to all ranks

- Scatter: distribute distinct pieces of a tensor to different ranks

- Gather: collect pieces from ranks onto a single destination

- Reduce: apply an associative, commutative operation (sum, min, max) while gathering results

- All-gather: concatenate/stack data from every rank onto every rank

- Reduce-scatter: reduce across ranks and scatter disjoint portions of the reduced result

-

All-reduce: functionally equivalent to reduce followed by all-gather; commonly used for synchronizing gradients in training

Correct use requires consistent matching of calls across ranks and agreement on shapes and orderings.

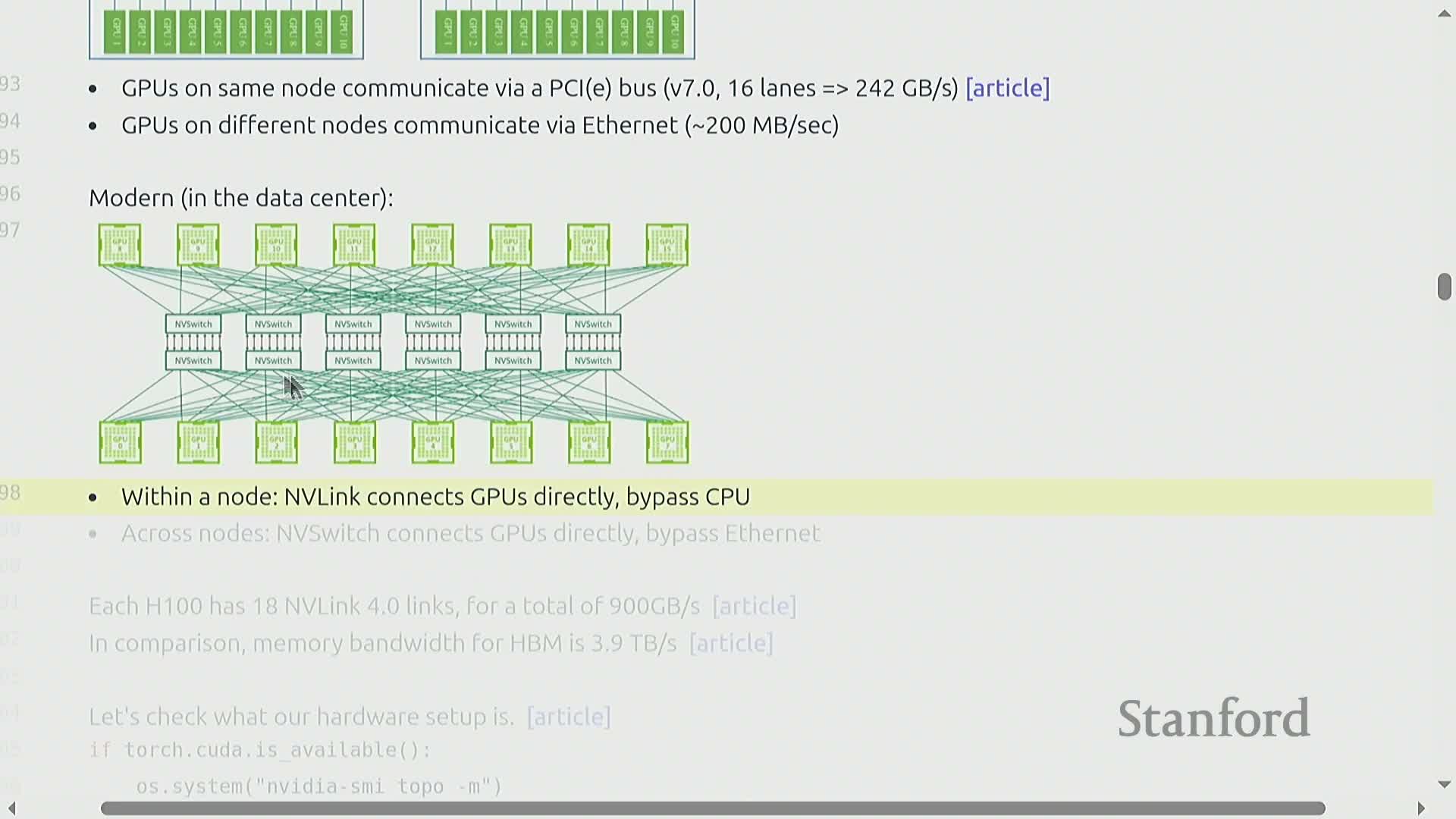

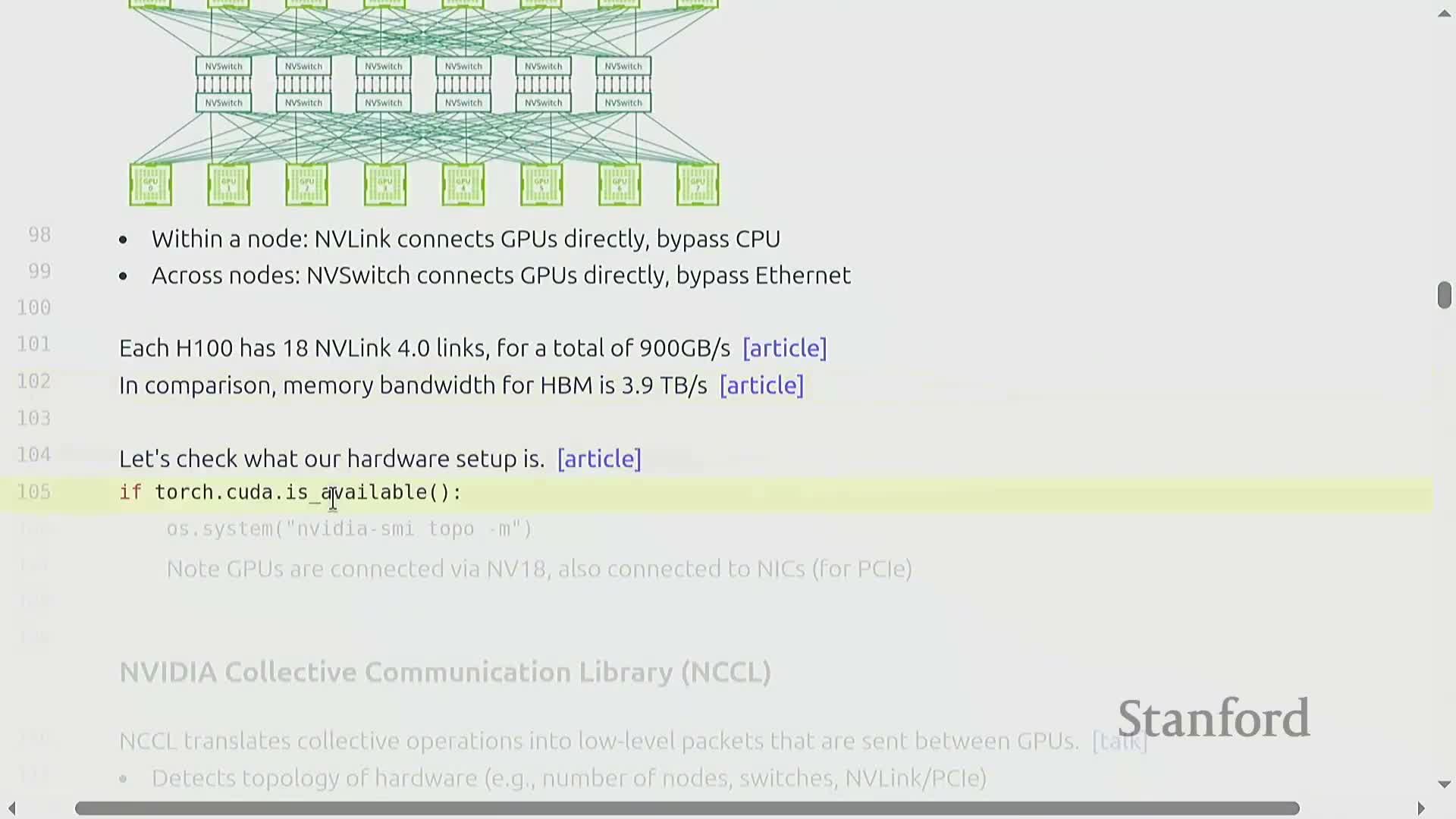

GPU system topologies form a hierarchy (SM L1, HBM, PCIe, NVLink, NVSwitch) and influence where and how collective communication is executed.

GPU nodes contain multiple memory and interconnect levels:

- Tiny on-SM L1 caches for immediate operands

- Larger high-bandwidth device memory (HBM) for layer state and activations

- Host-level links (PCIe) and cluster interconnects for cross-node transfers

Traditional GPU-to-GPU transfers used the host (PCIe + Ethernet), incurring kernel and copy overheads that throttled throughput.

Modern designs use device-aware interconnects such as NVLink and NVSwitch to bypass the host, providing much higher aggregate bandwidth and lower latency and thereby changing optimal communication strategies.

The relative costs of on-chip accesses vs. inter-node links determine whether replication, sharding, or recomputation is preferable in a design.

Topology-discovery tools reveal inter-GPU links such as NVLink and show how network cards and PCIe paths connect GPUs and CPUs, which affects communication strategies.

Topology visibility matters: system utilities report which GPU pairs are directly connected by high-bandwidth links and which require routing over PCIe or network interfaces.

Practical implications:

- In an eight-GPU node, many pairs are connected by NVLink lanes while other traffic still traverses PCIe or network adapters

- This heterogeneous connectivity influences collective implementations and performance optimizations

-

Network interface cards and the host CPU remain part of the topology for coordination and non-GPU backends

Correctly interpreting topology lets libraries and applications choose minimal-latency / maximum-bandwidth paths for collective transfers.

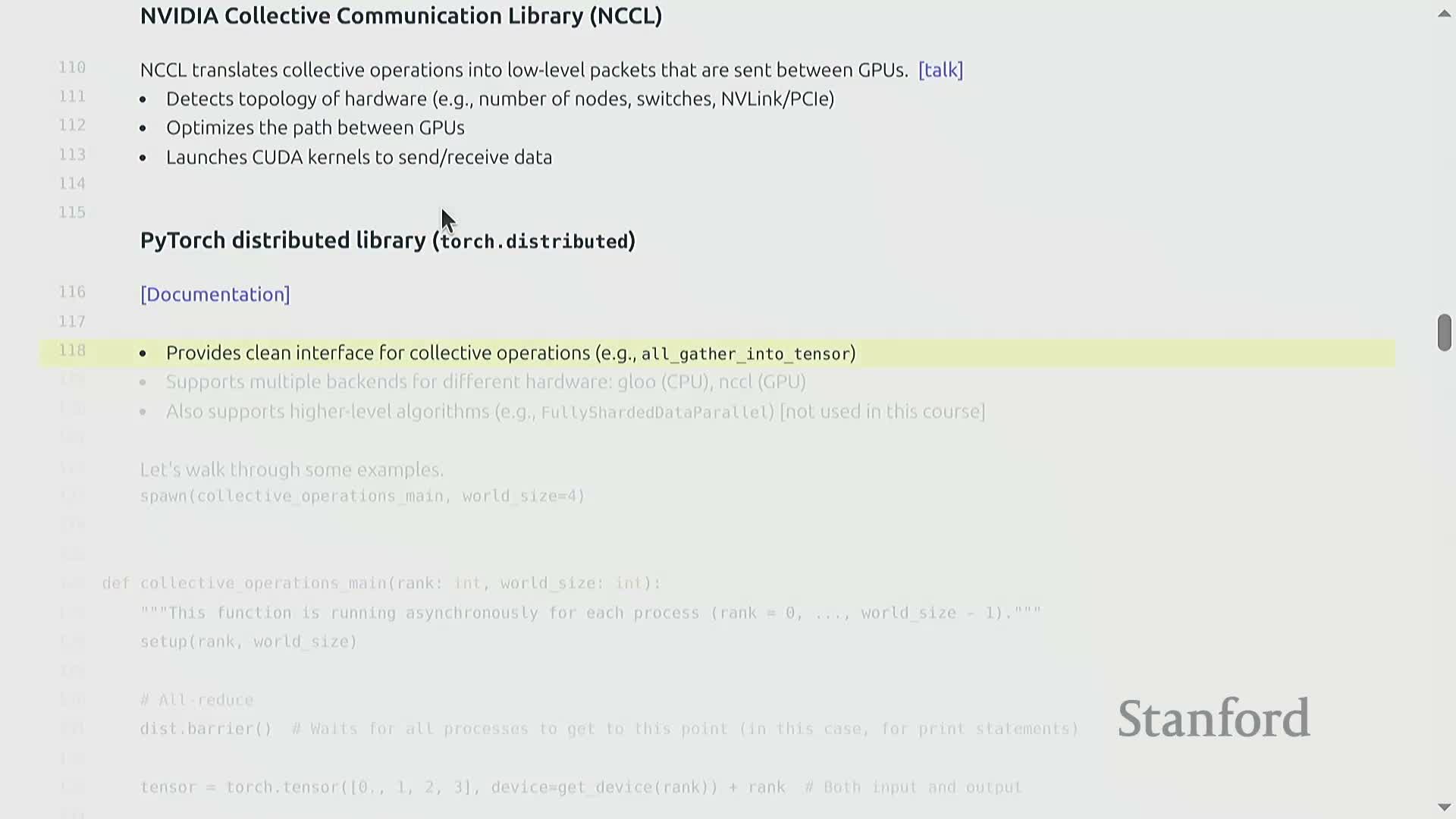

NCCL (NVIDIA Collective Communications Library) implements low-level GPU-aware collectives and torch.distributed provides a higher-level, multi-backend interface for Python workloads.

NCCL translates high-level collective semantics into optimized, hardware-aware packet transfers and CUDA kernels that move and reduce data across GPUs.

Key behaviors:

- Performs topology discovery and path optimization during initialization

- Emits device-side kernels and transfers that exploit link topology and in-network features where available

Higher-level frameworks expose these primitives:

- torch.distributed wraps backend libraries and exposes ops such as all-reduce, all-gather, reduce-scatter, and point-to-point sends/receives to Python programs

- Supports multiple backends (e.g., NCCL for GPUs, Gloo for CPUs), enabling portability while retaining backend-specific performance characteristics

These libraries also offer asynchronous operations and expert features for overlapping communication and computation, but exact performance depends on hardware, tensor sizes, and library internals.

Distributed processes must initialize a process group and use synchronization primitives like barrier to coordinate multi-process execution.

A typical distributed workload spawns multiple processes (commonly one per device) that run the same function with different rank indices.

Initialization process:

- Processes rendezvous via a host-based coordinator to establish a process group

- Initialization exchanges topology and membership info — distinct from the heavy tensor traffic handled by the collective library

- A barrier primitive provides an explicit synchronization point, useful for ordered side effects (logging), deterministic benchmarking, and coordination before launching collectives

Proper initialization and synchronization prevent mismatched collectives that would otherwise hang or deadlock.

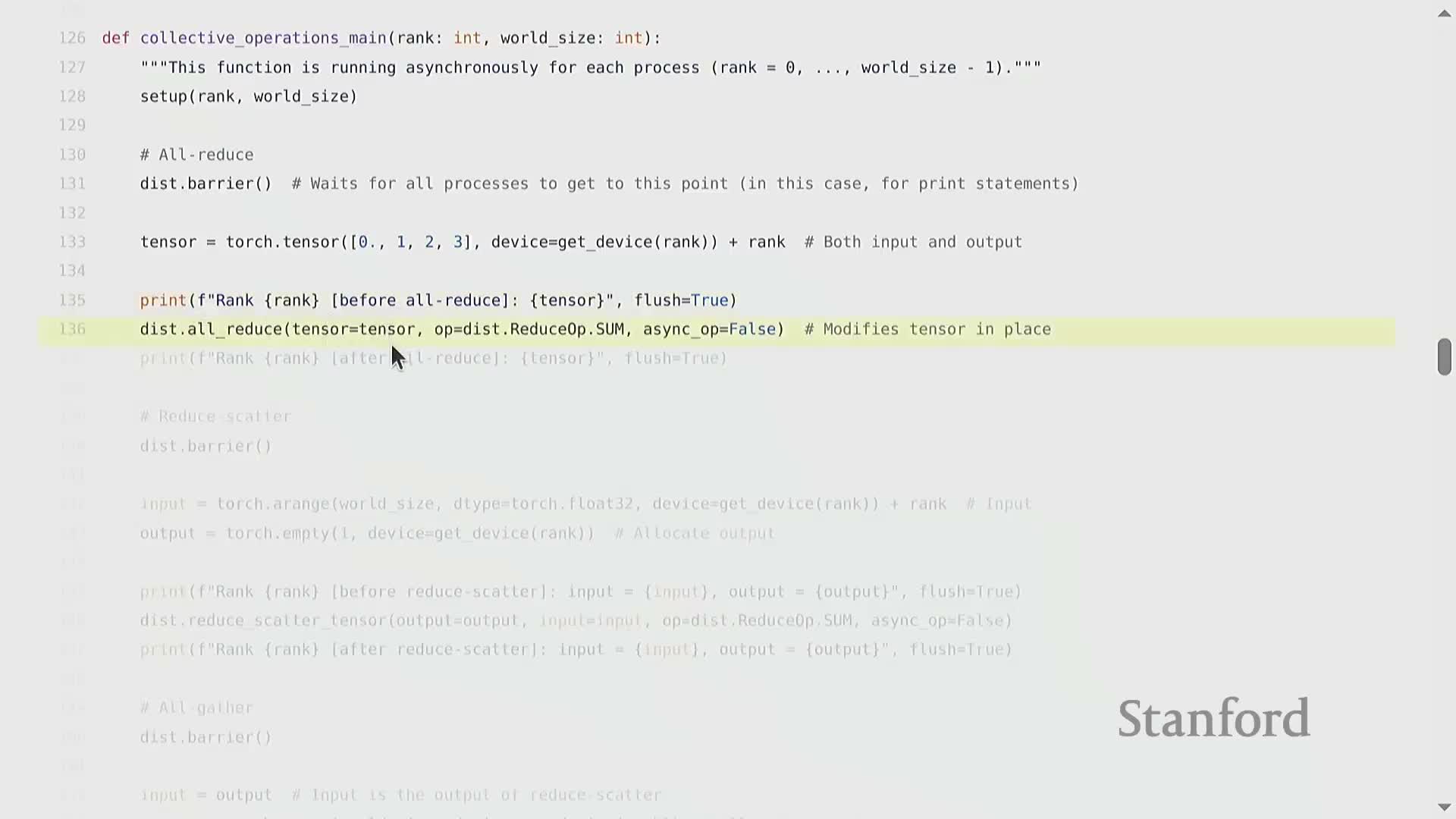

All-reduce aggregates values across ranks using an associative operation and places the same reduced result on every participating rank, typically in-place on the input tensor.

All-reduce applies a commutative, associative operation (typically sum or average) across corresponding tensor elements from every rank and writes the aggregated result back to the provided output (often in-place).

Practical notes:

- Implementations support synchronous and asynchronous variants; async all-reduce returns a handle to overlap communication with computation

- Canonical use: gradient synchronization in synchronous data-parallel training — all ranks obtain identical averaged gradients after backward pass

- Correct use requires matching collective calls and careful attention to tensor shapes and dtypes across ranks

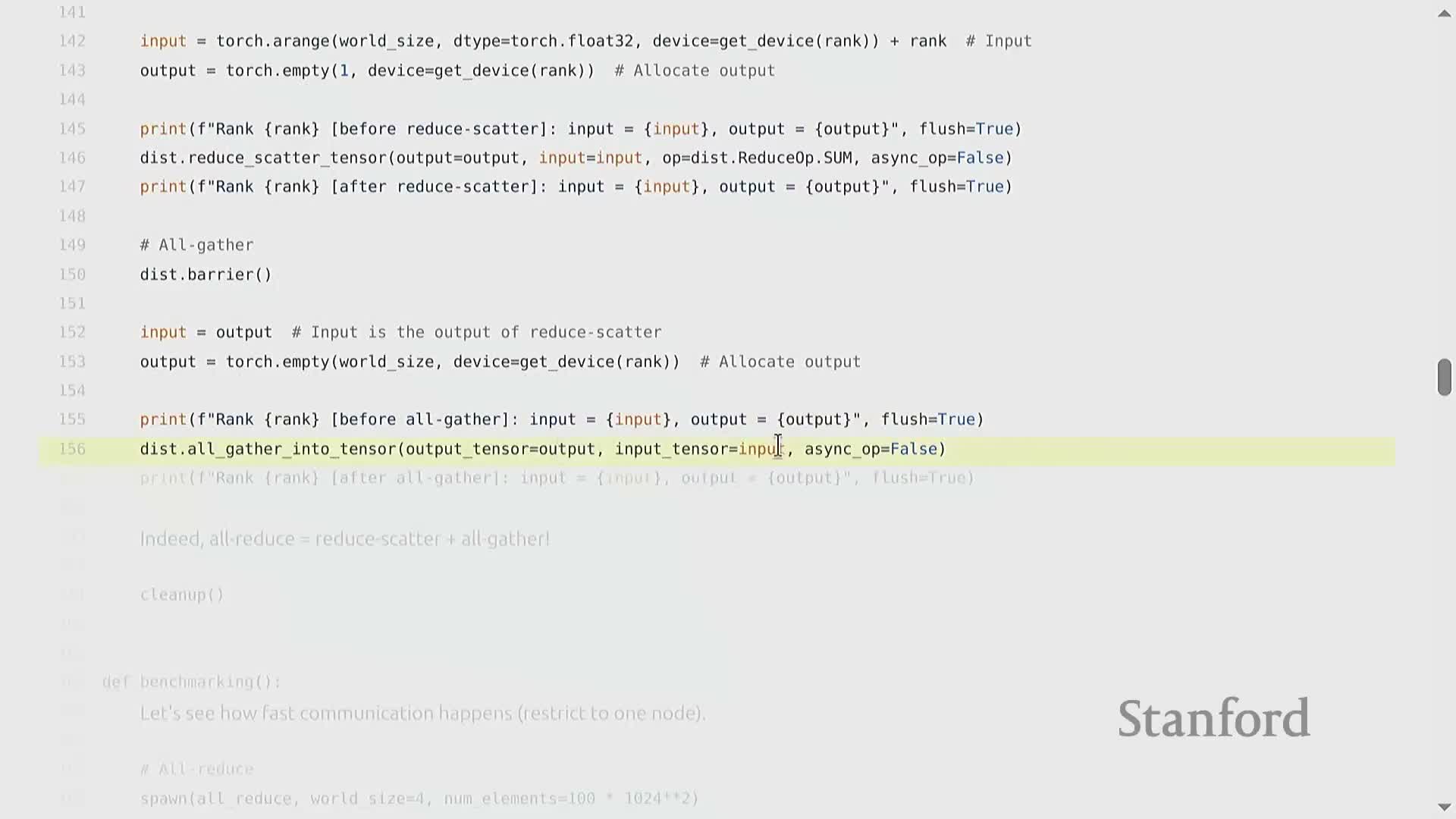

Reduce-scatter computes a reduction across ranks and distributes disjoint portions of the reduced tensor to different ranks, producing a smaller local output per rank.

Reduce-scatter combines reduction and scattering:

- Takes an input whose one dimension corresponds to world size and performs a per-segment reduction across ranks

- Delivers each reduced segment to the corresponding destination rank; the output is the per-rank portion (often smaller than the full tensor)

When to use:

- Useful when algorithms expect partitioned reduced outputs rather than full replication

- Can reduce total communication compared to separate reduce and scatter steps

Implementation caveats:

- Ensure dimension alignment and consistent element ordering so segments map to ranks deterministically

All-gather concatenates tensors from all ranks so that each rank ends up with the full collection, and when paired with reduce-scatter it composes to an all-reduce.

All-gather assembles a full tensor from per-rank inputs by concatenating or stacking so every rank receives the complete assembled tensor.

Usage patterns:

- Reconstruct full activation or parameter vectors when preceding stages computed only a shard

- Combined with reduce-scatter (reduce-scatter followed by all-gather) the composition is functionally equivalent to an all-reduce because the reduced segments are redistributed so every rank obtains the complete reduced result

All-gather is therefore a key building block for implementing higher-level collective behaviors from lower-level primitives.

Collective operations require consistent tensor shapes across ranks and a convention for which tensor dimension maps to devices in sharded operations.

Many collectives infer a mapping from a tensor dimension to world size (for example, reduce-scatter often assumes one dimension equals the number of devices and partitions along that axis).

Practical guidance:

- All ranks must supply tensors with compatible shapes and consistent partitioning rules

- Mismatched dimensionality or stride assumptions lead to runtime errors or incorrect placements

- Use small synthetic examples to test shape conventions before integrating collectives into larger code paths

Careful shape management simplifies debugging and ensures deterministic mapping from tensor segments to device ranks.

Reliable benchmarking of collectives requires warm-up, synchronization, and precise byte accounting to compute effective bandwidth.

Benchmark methodology essentials:

- Warm up kernels and CUDA context to avoid first-call overheads

-

Synchronize all ranks before timing to ensure consistent start and end points

Byte accounting:

- Depends on the operation: for all-reduce each rank contributes tensor bytes and typically sends and receives data such that a factor-of-two term appears in total traffic accounting (send plus receive)

-

Reduce-scatter omits the broadcast-back component in its accounting

Compute aggregate bandwidth as total transferred bytes divided by measured wall-clock duration. Results depend on tensor size, world size, backend optimizations, and topology — interpret benchmark results as relative comparisons across configurations rather than absolute hardware maxima.

Reduce-scatter benchmarks follow the same methodological steps as all-reduce but typically report different effective bandwidth due to different traffic patterns and less broadcast traffic.

Reduce-scatter benchmarking notes:

- Construct an input whose relevant dimension scales with world size, warm up kernels, synchronize, and measure elapsed time for the operation

- Because reduce-scatter reduces and scatters disjoint portions without a global broadcast back, its traffic accounting omits the round-trip factor present in all-reduce calculations — often yielding numerically smaller bandwidth estimates for the same element counts

Variations arise from backend optimizations (e.g., in-network aggregation) and hardware features, so interpretation requires careful comparison to theoretical link rates and other measurements.

End-to-end benchmarking is necessary to reveal real-world throughput characteristics for different collectives.

Distributed training strategies (data, tensor, pipeline) can be understood by applying them to a deep MLP as a representative compute-bound workload.

MLPs are a simple yet representative workload:

- Each layer is dominated by matrix multiplies and nonlinearities, making MLPs useful pedagogical examples for distributed strategies

- Parallelization strategies:

- Data parallelism: split the batch dimension

- Tensor parallelism: shard model dimensions (e.g., hidden width)

-

Pipeline parallelism: partition layers across devices

Examining these approaches on MLPs reveals core patterns that generalize to transformers while keeping implementation and reasoning tractable.

Data-parallel (DDP) training replicates the model on each device, partitions the batch across ranks, and synchronizes gradients via all-reduce after the backward pass.

Data-parallel training flow:

- Each rank receives a disjoint slice of the global minibatch and runs forward/backward on a full replica of the model

- After backward, an all-reduce averages gradients across ranks

- Each rank updates parameters with the same aggregated gradient, resulting in synchronized parameters across devices

Trade-offs:

- Scales straightforwardly with replicas

- Requires communicating gradients of the full model each step and synchronizing at the collective barrier point

Tensor parallelism shards parameter matrices (for example across the hidden dimension), computes local partial activations, and uses all-gather to assemble full activations for subsequent layers.

Tensor parallelism:

- Divides model tensors along one or more model dimensions so each rank stores and computes on only a slice of each layer’s parameters

- Forward pass: each rank computes partial activations for its shard; an all-gather assembles the full activation required by the next stage

- Backward pass: symmetric communication propagates gradients to the appropriate parameter shards and typically mirrors the forward communication pattern

Trade-offs: reduces memory footprint per device but increases interconnect traffic for activations and intermediates, so it benefits from high-bandwidth, low-latency links.

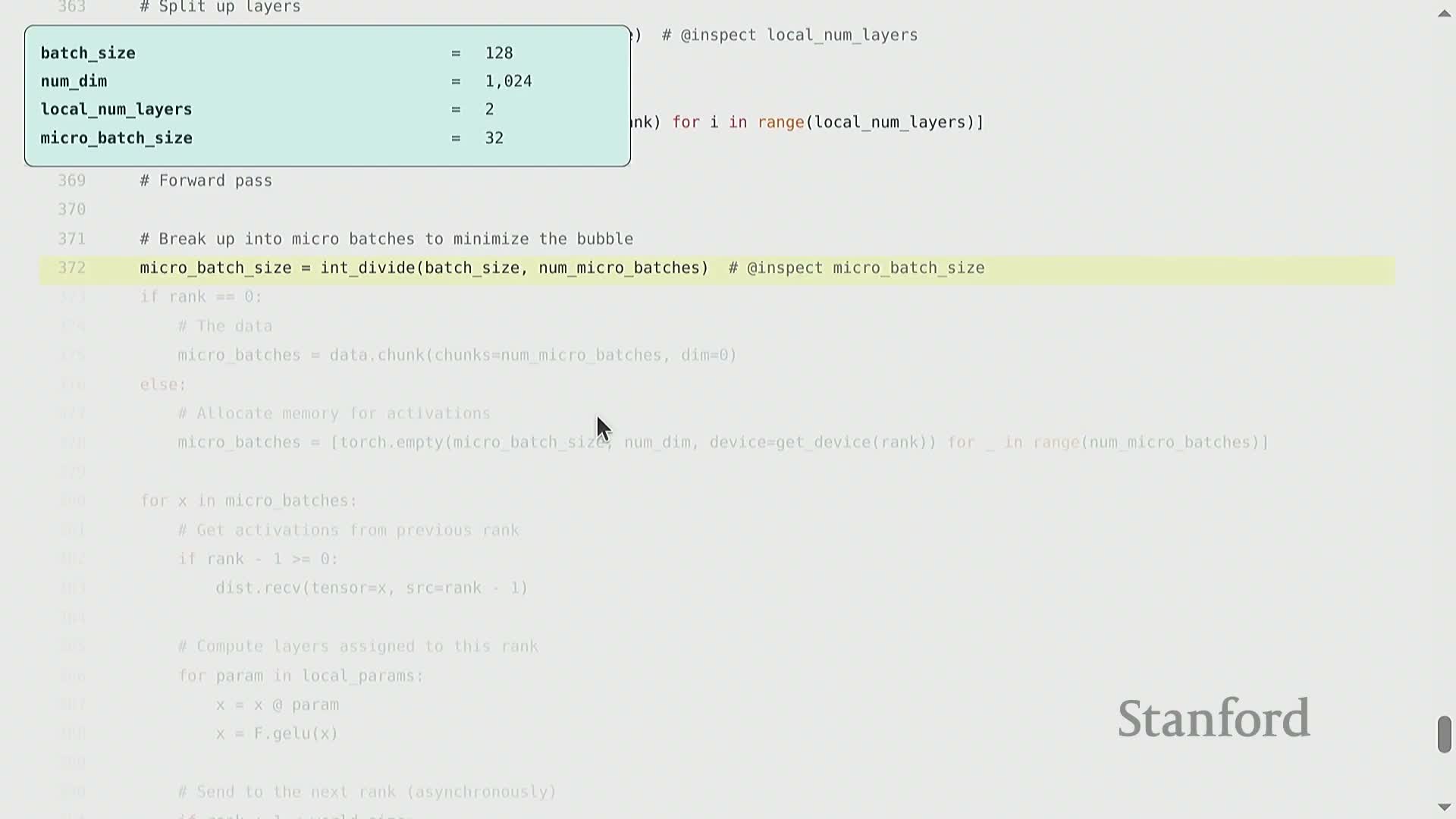

Pipeline parallelism partitions layers across devices and streams microbatches through the partitioned model using point-to-point sends and receives to improve utilization.

Pipeline parallelism assigns contiguous layer groups to different ranks so each rank is responsible for a stage of the network.

Streaming with microbatches:

- Subdivide the global batch into microbatches

- Stream microbatches through stages; each stage receives activations from the previous stage, computes local layers, and forwards activations to the next stage via point-to-point sends/receives

- Interleave forward and backward microbatches to keep stages busy and reduce pipeline bubbles

Implementation notes:

- Uses send/receive primitives rather than collectives

- Naive implementations suffer from idle pipeline bubbles and synchronous blocking

- Advanced implementations use asynchronous sends/receives, microbatching, and careful scheduling to overlap compute and communication and minimize stalls

Overlapping communication and computation via asynchronous sends/receives and handles reduces stalls and improves GPU utilization in pipeline and other parallel schemes.

Modern collective and point-to-point APIs provide asynchronous variants that return completion handles so communication can be launched while computation continues on other streams.

Common pattern:

- Launch nonblocking sends/receives (device-side kernels move data independently of the CPU thread)

- Continue useful computation (process other microbatches, local work)

-

Synchronize on handles before accessing transferred data to ensure correctness

Caveats:

- Ordering of multiple sends to the same destination is preserved by stream semantics, but matching receives and careful coordination are required to avoid mismatches.

Full pipeline training requires coordinating forwards and backwards across ranks, handling last-stage loss computation, and implementing backward-stage sends to propagate gradients upstream.

In a complete pipeline implementation the final stage computes the loss for a microbatch and initiates backward propagation by computing gradients and sending contributions back to the previous stage.

Backward scheduling:

- Must be interleaved with forward microbatches to avoid deadlocks and minimize stalls — more complex than forward-only streaming logic

- Requires bookkeeping for which microbatch corresponds to which backward activation

- Often uses asynchronous operations to overlap communications and computation

Production systems typically encapsulate this complexity in libraries that manage ordering, handles, and partial failures instead of leaving manual control to application code.

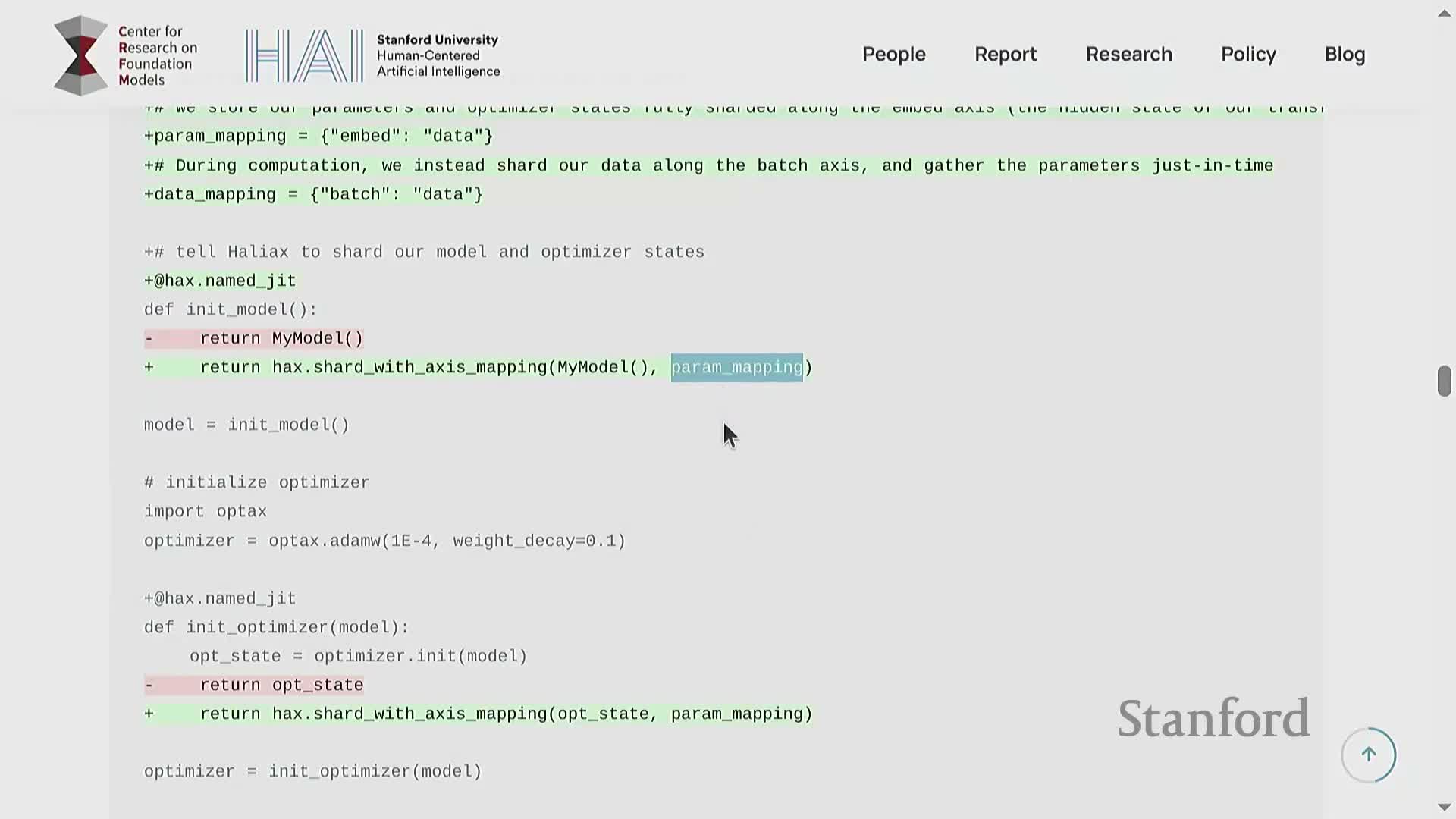

High-level frameworks such as JAX expose sharding primitives so users can specify how tensor dimensions are partitioned and let the compiler generate the underlying communication and kernel launches.

JAX and similar systems let users declare data and model sharding by mapping tensor axes to device axes; the compiler synthesizes the required collectives and kernel code to realize the sharding across available devices.

Tooling:

- Higher-level toolkits (e.g., the referenced Lavanter example) allow concise specifications of FSDP or tensor-parallel strategies in only a few lines of code

- Benefit: conceptual simplicity and portability — users describe partitioning and the system optimizes mapping and communication

- Trade-off: less direct low-level control compared to hand-crafted PyTorch + NCCL implementations, though compiler-generated code is often sufficiently performant and much easier to maintain

Parallelization choices trade off computation, communication, and memory; recomputation, checkpointing, and sharding are recurring techniques, and hardware evolution maintains a multi-level hierarchy of limits.

Parallelization can be viewed as cutting either the data or various model dimensions:

- Batch (data)

- Width/hidden (tensor parallelism)

- Depth/layers (pipeline parallelism)

- Context/sequence length (e.g., for sequences)

Memory vs. compute trade-offs:

- Activation checkpointing (recompute on demand) trades extra compute for reduced memory and fewer transfers

- Alternatively, storing activations or moving them to remote device memory trades memory pressure for communication overhead

Hardware trends:

- Increases in on-chip memory and link bandwidth shift but do not eliminate trade-offs, since model size tends to grow in parallel with hardware capabilities

- Understanding the trade space and available library primitives is necessary to design scalable training systems rather than relying solely on future hardware advances

Practical implementation questions include handling data-dependent state (batchnorm), using high-level libraries (FSDP), activation checkpointing APIs, specialized hardware trade-offs, incremental training, and how collectives are executed at runtime.

Batch-dependent statistics (e.g., BatchNorm) introduce global state that complicates naive data-parallel schemes, whereas normalization methods that do not depend on batch-wide statistics (e.g., LayerNorm) avoid that problem.

Distributed solutions and tooling:

- Synchronize batch statistics across ranks or use normalization variants suited to sharded training

- PyTorch provides higher-level solutions such as FSDP for parameter sharding and memory-efficient training

- Both PyTorch and JAX expose activation checkpointing APIs to selectively recompute activations and trade compute for memory

Other considerations:

- Specialized inference/training hardware (Cerebras, GROQ) emphasizes large on-chip memory and different trade-offs, reducing communication but possibly limiting flexibility

- Incremental/continued training is conceptually straightforward (gradient steps and checkpoints) but requires practical handling of optimizer state placement and consistency

Runtime orchestration:

- The CPU typically invokes libraries (NCCL, Gloo) to orchestrate collectives; those libraries launch GPU kernels and manage device-side transfers so data movement and reductions execute efficiently on the devices themselves.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: