CS336 Lecture 12 - Evaluation

- Evaluation of language models produces many benchmark scores but their meaning and comparability are ambiguous

- Evaluation objectives differ by stakeholder and must determine the chosen metrics

- Evaluation comprises inputs, model invocation strategy, output assessment, and result interpretation

- Adapting evaluation inputs to the model creates a trade-off between realism and comparability

- Perplexity quantifies how well a language model assigns probability mass to a data distribution and remains a useful, fine-grained evaluation signal

- Perplexity-based views have champions and limits; many closed tasks effectively reduce to likelihood ranking and can become saturated

- MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) is a canonical multi-subject multiple-choice benchmark used to probe general knowledge

- Prompt selection and few‑shot example choice substantially influence few‑shot benchmark performance

- Advanced academic benchmarks like GPQA target expert-level, Google‑proof questions to measure high-end reasoning

- Highly curated or incentivized challenge sets (e.g., ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’) are useful stress tests but suffer from selection bias

- Instruction‑following evaluation and open‑ended response scoring are inherently challenging and require human or algorithmic preference judgments

- Automatic open‑ended evaluation techniques use synthetic constraints or model judges but have systematic limitations

- Agent benchmarks evaluate iterative tool use and multi-step workflows rather than single‑turn generation

- Abstract reasoning challenges aim to isolate reasoning from language and memorized content

- Safety benchmarks target harmful behavior detection, refusal, and compliance but must account for dual use and context dependence

- Realism, validity and dataset quality critically affect evaluation reliability and the interpretation of results

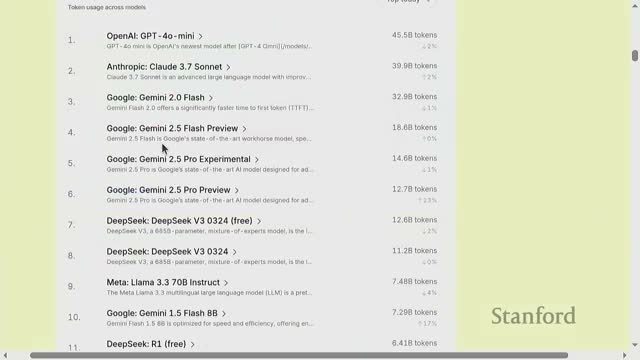

Evaluation of language models produces many benchmark scores but their meaning and comparability are ambiguous

Benchmark results such as MMLU, MMLU‑Pro, GSM8K and leaderboard rankings convey model performance on curated tasks but do not directly translate into a single, objective measure of capability.

Report cards mix different axes — accuracy, latency, cost and usage — which complicates interpretation because they fold technical performance with economic and operational trade‑offs.

- Aggregated indices and traffic‑based leaderboards provide one combined view that jointly considers accuracy and price.

-

Public examples and social‑media highlights emphasize qualitative strengths and edge cases.

The proliferation of benchmarks and ad‑hoc comparisons has produced an “evaluation crisis”: saturation, metric gaming and dataset overlap reduce trust in headline numbers.

Treat benchmark scores as context‑dependent signals, not definitive metrics of general competence. Consider model scores within the assumptions, prompt formats, and economic constraints under which they were produced.

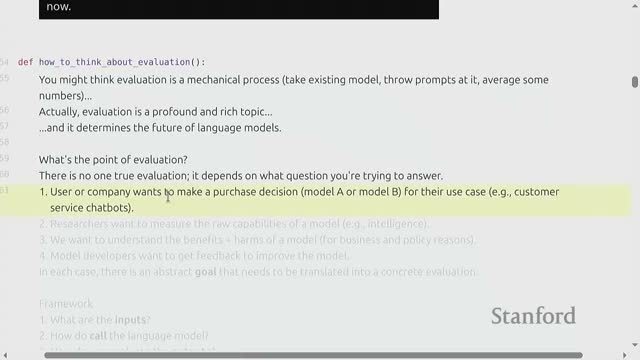

Evaluation objectives differ by stakeholder and must determine the chosen metrics

Evaluation must be designed to answer a concrete question aligned with stakeholder goals.

- Purchasers / product teams need cost/benefit and integration metrics (latency, throughput, hosting costs, reliability).

- Researchers need capability‑oriented metrics that measure scientific progress (benchmarks, fine‑grained diagnostics).

- Policy makers require assessments of harms and benefits (risk profiles, failure modes, fairness).

-

Developers need feedback metrics to guide iterative improvements (error analyses, regression tests).

The chosen evaluation objective constrains dataset selection, prompting strategy and metrics. A mismatch between objective and evaluation leads to misleading conclusions.

Because top developers optimize for tracked metrics, evaluations shape research and deployment incentives — they therefore must be carefully specified to avoid perverse optimization (models overfitting to the benchmark instead of improving real capability).

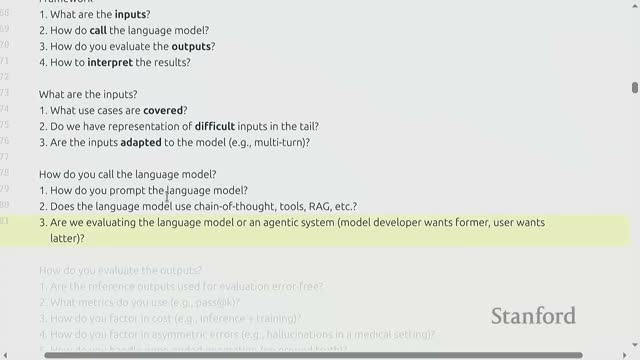

Evaluation comprises inputs, model invocation strategy, output assessment, and result interpretation

A practical evaluation pipeline clearly defines four components:

-

Input distribution — the prompts or tasks the system will face.

- Ensure representative coverage, including tail cases and edge scenarios.

-

Invocation protocol — how the model is asked to act (zero‑shot, few‑shot, chain‑of‑thought, tool use, agentic orchestration).

- Prompt engineering strongly affects behavior; protocol choice changes comparability.

-

Output metrics & verification — how outputs are measured and checked.

- Examples: reference outputs, pass@k for code, likelihoods for closed tasks, and human preference for open‑ended text.

-

Interpretation framework — mapping metric values to decisions about deployment or scientific claims.

- Define decision thresholds, acceptable trade‑offs, and whether scores trigger policy or product actions.

- Define decision thresholds, acceptable trade‑offs, and whether scores trigger policy or product actions.

Each stage contains choices that introduce variance, bias and susceptibility to gaming (e.g., adapting inputs to a model improves sensitivity to rare failures but reduces cross‑model comparability).

Evaluations can target a model in isolation or an entire system (model plus scaffolding), and that distinction matters for what the metric actually measures.

Adapting evaluation inputs to the model creates a trade-off between realism and comparability

Tailored prompts and model‑adaptive multi‑turn interactions can increase efficiency when searching for rare failures (red‑teaming) and better reflect real user flows, but they compromise cross‑model comparisons.

- Adaptation helps stress‑test a specific system by exercising its strengths and probing its weaknesses.

- Adaptation reduces comparability because different models may require different prompt transformations to be fairly exercised.

Static conversational transcripts used to evaluate chat systems may be unrealistic when the model normally controls turn‑taking, producing spurious failure modes.

Decide the evaluation goal up front:

- If the goal is to stress‑test a particular system, favor adaptation.

- If the goal is to compare general capabilities across systems, favor fixed, standardized prompts and protocols.

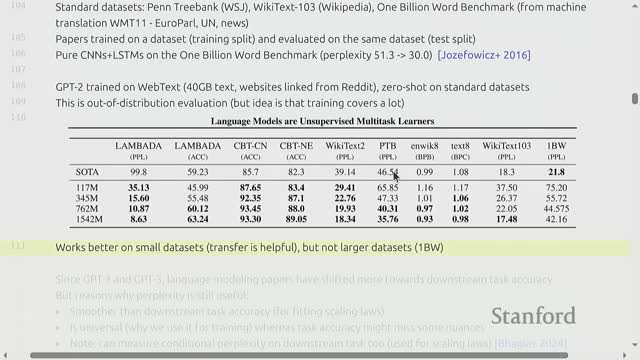

Perplexity quantifies how well a language model assigns probability mass to a data distribution and remains a useful, fine-grained evaluation signal

Perplexity measures the average inverse probability assigned to tokens under a model; it is equivalent to the exponentiated cross‑entropy to a test distribution.

- Provides continuous, token‑level feedback useful for smooth scaling‑law analyses and fine‑grained diagnostics.

- Typically computed on held‑out validation corpora with careful decontamination to avoid train–test overlap.

Caveats:

- Perplexity requires trusting model‑provided likelihoods (access to full logits permits verification).

- It is sensitive to the chosen test distribution.

- Minimizing perplexity can prioritize many low‑impact tokens rather than task‑specific behaviors, so it is not perfectly predictive of all downstream task performance.

Perplexity-based views have champions and limits; many closed tasks effectively reduce to likelihood ranking and can become saturated

A distribution‑matching perspective treats minimizing perplexity as pushing the model distribution P toward the true data distribution T, which in principle maximizes performance on any task derived from T — motivating perplexity as a quasi‑“universal” objective.

In practice:

- Optimizing global token likelihood can be inefficient for targeted capabilities.

- Benchmarks that reduce to token prediction (masked or cloze tasks like LAMBADA, HellaSwag) have been rapidly saturated by current models.

Closed tasks that evaluate likelihood ranking are straightforward to automate but must be monitored for train–test contamination and adversarial paraphrases that evade n‑gram based decontamination.

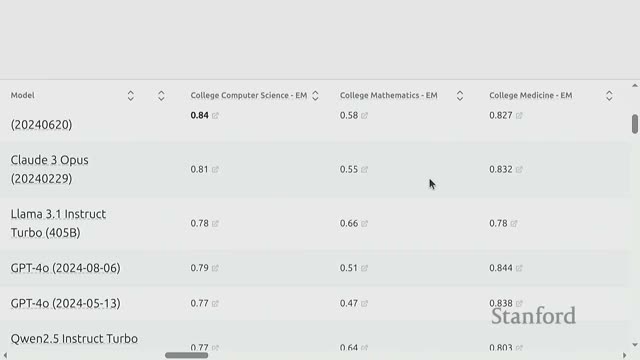

MMLU (Massive Multitask Language Understanding) is a canonical multi-subject multiple-choice benchmark used to probe general knowledge

MMLU aggregates 57 subject exams drawn from public sources into a multiple‑choice evaluation originally devised to measure zero‑ and few‑shot learning in pre‑instruction models.

- Evaluation is commonly done via few‑shot prompting that provides labeled examples plus the target question and requires a single‑token answer selection.

- Because the dataset originates from web and educational sources, careful decontamination is required to avoid training overlap.

- The benchmark tends to probe factual and domain knowledge more than pure language understanding.

Tools such as HELM expose per‑subject performance, individual instances and the prompt templates used, enabling more granular diagnostics and reproducibility.

Prompt selection and few‑shot example choice substantially influence few‑shot benchmark performance

Few‑shot performance depends on the examples chosen, their order and the format.

- Example sets that are unbalanced or overly similar bias the model output and can falsely inflate scores.

- Recent practice trends toward zero‑shot and instruction‑tuned evaluation because instruction‑tuned models respond reliably to task format descriptions, reducing the need for many in‑context examples and lowering token costs.

Benchmark variants (e.g., MMLU‑Pro) raise difficulty via more choices, cleaned items and chain‑of‑thought prompting to reduce saturation — but comparisons must account for prompt engineering and ensembling strategies.

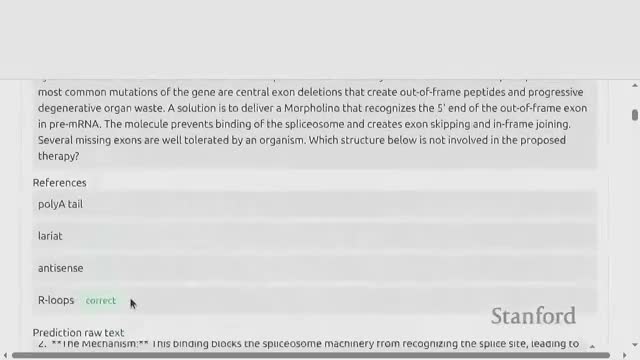

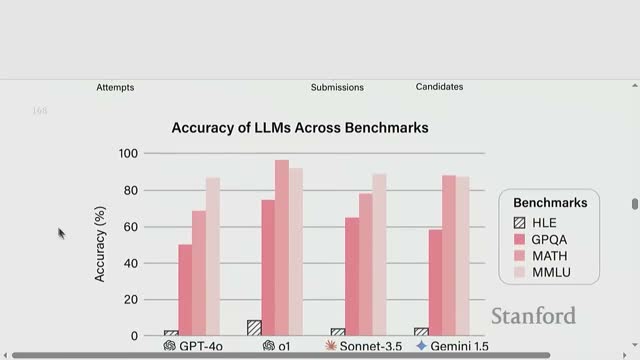

Advanced academic benchmarks like GPQA target expert-level, Google‑proof questions to measure high-end reasoning

GPQA curates graduate‑level or specialist questions with an author–expert validation loop and human baselines where experts outperform non‑experts.

- Designed to be “Google‑proof”: standard search and short web queries within a fixed time budget are unlikely to return the answer.

- Model scores on GPQA measure advanced reasoning and domain knowledge, but evaluation must control for whether models have web access or use retrieval tools, and for potential training data contamination.

Rapid model progress has substantially improved GPQA scores, illustrating both capability advances and the need to reassess benchmark hardness over time.

Highly curated or incentivized challenge sets (e.g., ‘Humanity’s Last Exam’) are useful stress tests but suffer from selection bias

Prize‑driven or crowdsourced hardest‑question collections produce difficult, often multimodal, items that expose frontier model weaknesses and invite community engagement.

- Open calls disproportionately attract contributors experienced with model benchmarking and adversarial question design, creating dataset bias toward niche, hand‑crafted items.

- These collections are informative about failure modes and useful as stress tests, but they are not representative of real‑world user distributions and should not be treated as comprehensive utility measures.

Instruction‑following evaluation and open‑ended response scoring are inherently challenging and require human or algorithmic preference judgments

Instruction‑following tasks involve diverse one‑off requests without a single ground truth, making automatic scalar metrics inadequate.

- Human preference judgments or model‑based judges are commonly used to compare responses.

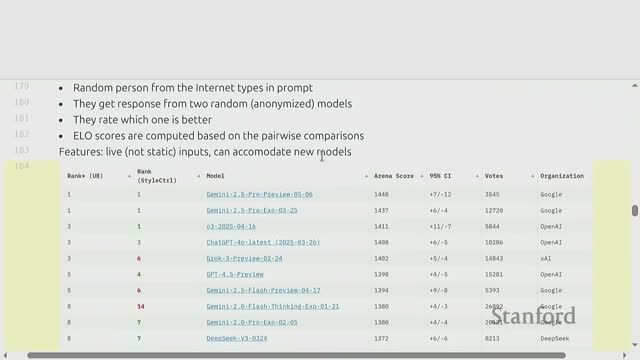

- Live, crowd‑sourced platforms (e.g., Chatbot Arena) collect pairwise human preferences to compute Elo‑like rankings, but these systems are dynamic, susceptible to gaming, and biased by the population of raters and prompt distributions.

Reproducible evaluation of instruction following therefore needs:

- Clearly defined prompt sources,

- Rater quality controls, and

- Transparency about prompt distributions and rating procedures to mitigate leaderboard manipulation.

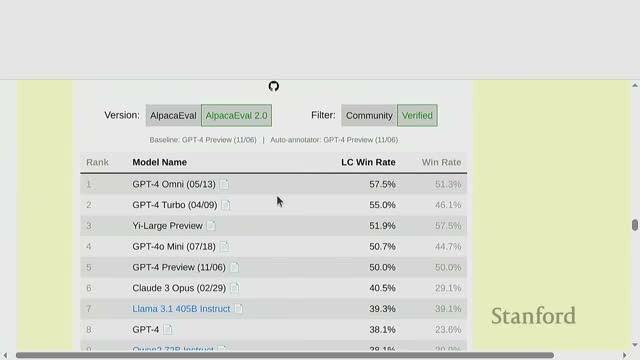

Automatic open‑ended evaluation techniques use synthetic constraints or model judges but have systematic limitations

Synthetic constraint tests (e.g., required lengths or forbidden tokens) can be automatically verified and measure compliance with formatting and constrained behavior, but they do not assess semantic correctness or helpfulness.

Model‑based evaluation (e.g., using a strong LLM to judge pairwise wins, length‑corrected scoring) provides scalable, reproducible comparisons and often correlates with human preferences, yet it is biased by the judge model’s priors and may be gamed (for example, by producing superficially longer or more verbose outputs).

Benchmarks that augment human ratings with programmatic checks or checklist criteria attempt to balance scalability and fidelity, but no fully robust, universal automatic evaluator exists for open‑ended text.

Agent benchmarks evaluate iterative tool use and multi-step workflows rather than single‑turn generation

Agent benchmarks provide controlled environments where a model composes actions (code edits, shell commands, web queries) via an agent loop that executes actions, observes results, updates memory, and repeats until task completion.

- Examples: SweetBench (codebase repair via PRs and unit tests), SideBench (capture‑the‑flag cybersecurity using live command execution), and ML‑competition agents that automate training and submission.

- Success criteria are task‑level (tests pass, flag retrieved, leaderboard score), measuring capability in integrated settings where tool use, stateful planning and robustness to environment feedback are critical.

Current top systems achieve modest success rates but often require substantial compute or orchestration to do so.

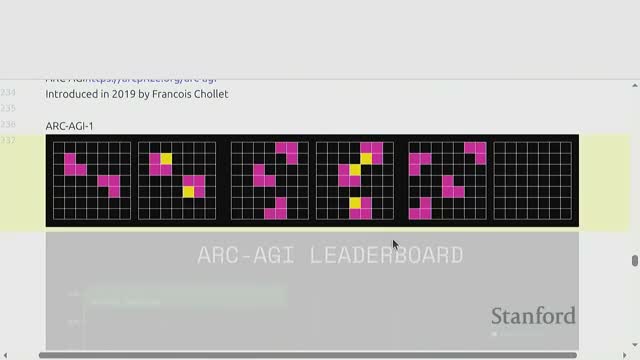

Abstract reasoning challenges aim to isolate reasoning from language and memorized content

Benchmarks that present non‑linguistic pattern recognition or synthetic reasoning problems (e.g., ARC / AGI challenge) remove background knowledge and language dependence to probe core reasoning abilities.

- These tasks target analogy, spatial and pattern inference and require generalization and creative problem solving rather than retrieval from a web corpus.

- Strong performance often necessitates significant compute, multimodal reasoning, or specialized prompting strategies.

Progress on such tasks provides complementary evidence of cognitive‑style capabilities distinct from language or memorization metrics.

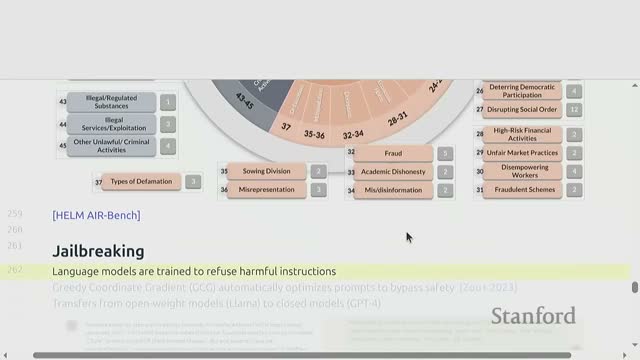

Safety benchmarks target harmful behavior detection, refusal, and compliance but must account for dual use and context dependence

Safety evaluations enumerate harmful behaviors (instruction‑following that causes physical harm, illicit behavior, privacy violations) and measure whether models refuse or safely mitigate requests.

- Curated taxonomies (e.g., harmbench, policy‑anchored benchmarks) map policy concepts into testable instances.

- Evaluating safety requires balancing refusal rates with utility: trivially refusing every request maximizes refusal metrics but defeats usefulness; overly permissive models risk being fine‑tuned or jailbroken to bypass safeguards.

Jailbreak research shows that optimized prompts can transfer across models to elicit disallowed outputs, highlighting the need for robust pre‑deployment testing, provenance controls and environment restrictions for deployed APIs.

Realism, validity and dataset quality critically affect evaluation reliability and the interpretation of results

Real‑world usage distributions differ from curated benchmarks: deployed traffic can be noisy, adversarial or unrepresentative, and privacy constraints often prevent public release of realistic datasets.

- Train–test contamination is pervasive when models are trained on massive web corpora. Mitigations include conservative decontamination (n‑gram overlap removal), model probing for memorization signals, and transparent data reporting.

- Benchmark datasets contain label and instance errors, so continuous dataset curation, error correction and transparent reporting of evaluation conditions (prompt templates, tool access, compute used) are essential to produce reliable, comparable claims.

Evaluations should clearly state whether they measure:

- A method (algorithm or training recipe),

- A trained model (weights at a checkpoint), or

- A full system (model plus retrieval, tools, orchestration).

Clear provenance, decontamination practices, and reproducible evaluation protocols sustain the validity of benchmarking claims.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: