CS336 Lecture 14 - Data - Part 2

- Lecture overview and objectives

- Filtering primitive: target set selection from raw data

- N-gram (statistical) language models for fast scoring

- Using n-gram perplexity for dataset filtering (CCNet example)

- FastText linear classifiers with hashed n-gram features for filtering

- Importance resampling and distributional data selection

- Unified scoring recipe for model-based filtering

- Limitations of local statistical filters and adversarial risks

- Language identification with FastText for corpus selection

- Domain-specific data curation case study: OpenWebMath

- Quality filtering strategies and synthetic labeling

- Toxicity filtering with annotated datasets and lightweight classifiers

- Deduplication: exact and near-duplicate categories and motivations

- Design space and hashing primitives for scalable deduplication

- Bloom filter approximate set membership for exact-duplication detection

- Similarity measures, MinHash and probabilistic reduction of Jaccard

- Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) with banding to amplify thresholds

- Practical considerations: embeddings for paraphrase-sensitive deduplication and duplicate handling policies

- Lecture summary and next steps

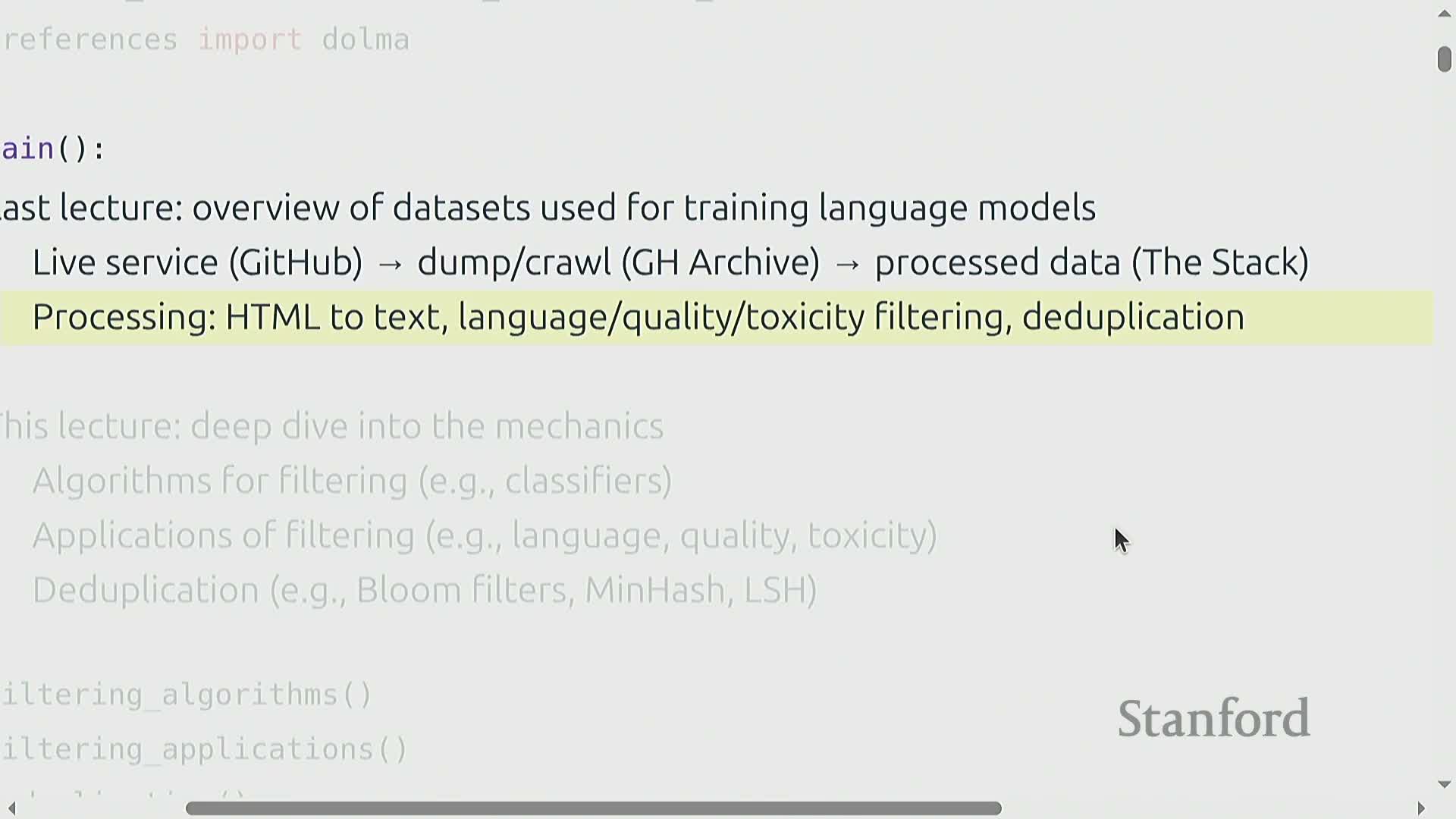

Lecture overview and objectives

This lecture presents a detailed treatment of data collection, preprocessing, quality filtering, and deduplication techniques used to prepare large web-scale corpora for language model training.

It frames the problem as extracting a high-quality target subset from massive raw sources and outlines the lecture plan:

-

Review model-based filtering algorithms — survey approaches that score or classify documents for inclusion.

-

Show how a single primitive supports multiple filtering tasks — demonstrate reuse of core operations across different filters.

-

Describe algorithms for exact and near-duplicate detection — cover methods for identifying identical and similar documents at scale.

The discussion emphasizes practical constraints:

-

Compute cost and the need to minimize expensive operations

-

Scalability to web-scale data and engineering trade-offs for throughput and storage

- Preference for fast, approximate methods over costly per-document model inference when processing billions of documents

The presentation positions the material as algorithmic building blocks for production data pipelines, not a purely theoretical treatment — focusing on techniques that are practical, efficient, and deployable at web scale.

Filtering primitive: target set selection from raw data

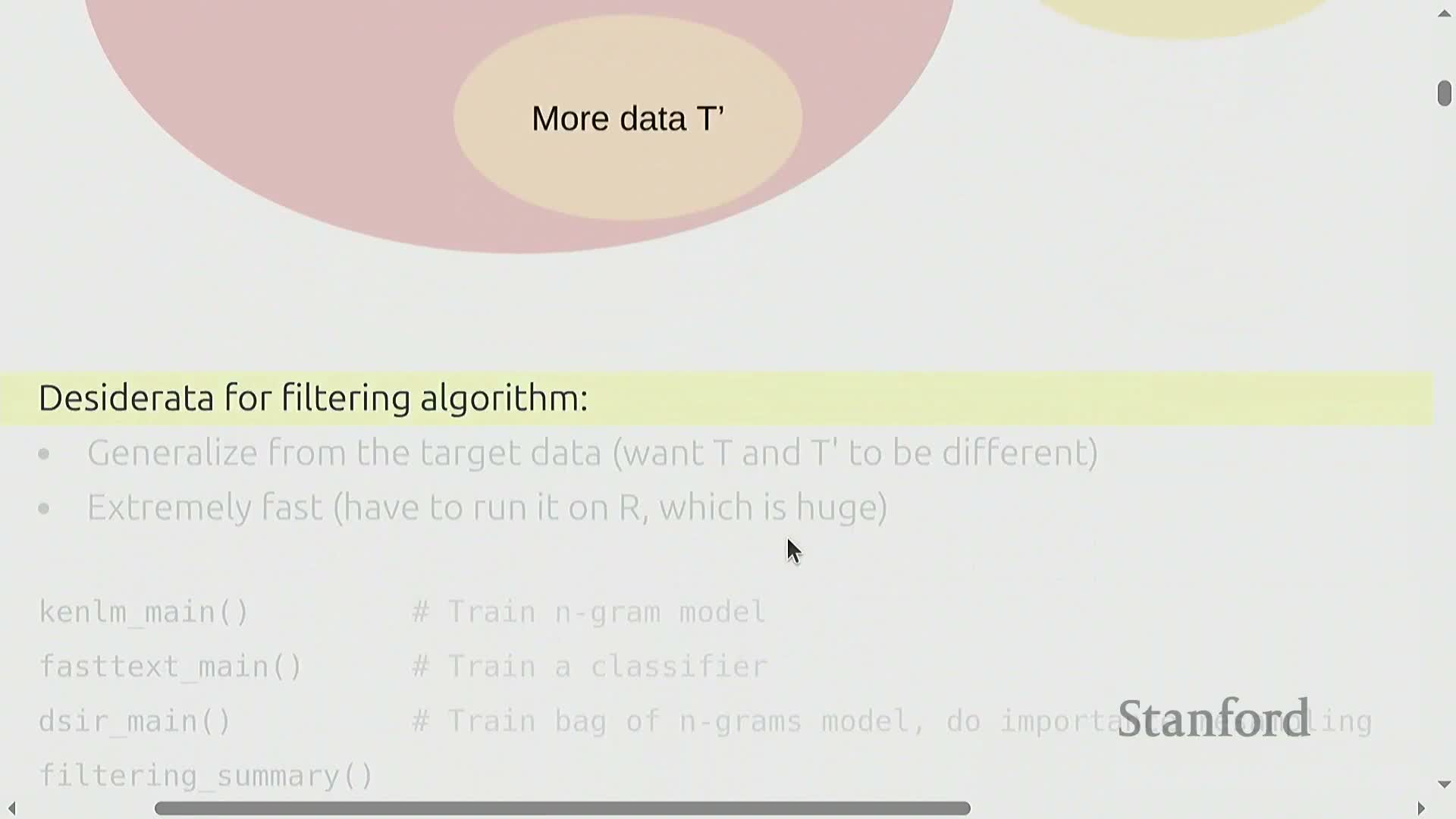

Filtering for model training is cast as selecting a subset T’ from a large raw dataset R that is similar to a small, high-quality target dataset T.

The primitive must generalize beyond exact copies of T and execute at web-scale under strict performance constraints.

The selection workflow (typical implementation):

- Fit one or more models on T and/or R to capture relevance or quality signals.

- Use those models to produce a per-document score (the scoring function).

- Convert scores into a subset T’ via thresholding or stochastic sampling.

Two primary operational requirements:

-

Statistical generalization from a limited T — the filter must identify useful, non-identical examples that match the target distribution.

-

Computational efficiency sufficient to process billions of web documents — the method must meet strict throughput and cost constraints.

These requirements drive the compute vs. selection-quality trade-off:

-

Lightweight statistical models — low compute, fast at scale, sometimes weaker selection fidelity.

-

Linear classifiers — middle ground in cost and accuracy for many problems.

-

Neural methods — higher selection quality but much higher compute and infrastructure demands.

The filtering abstraction therefore guides method choice by balancing selection quality against scalability and cost for web-scale dataset curation.

N-gram (statistical) language models for fast scoring

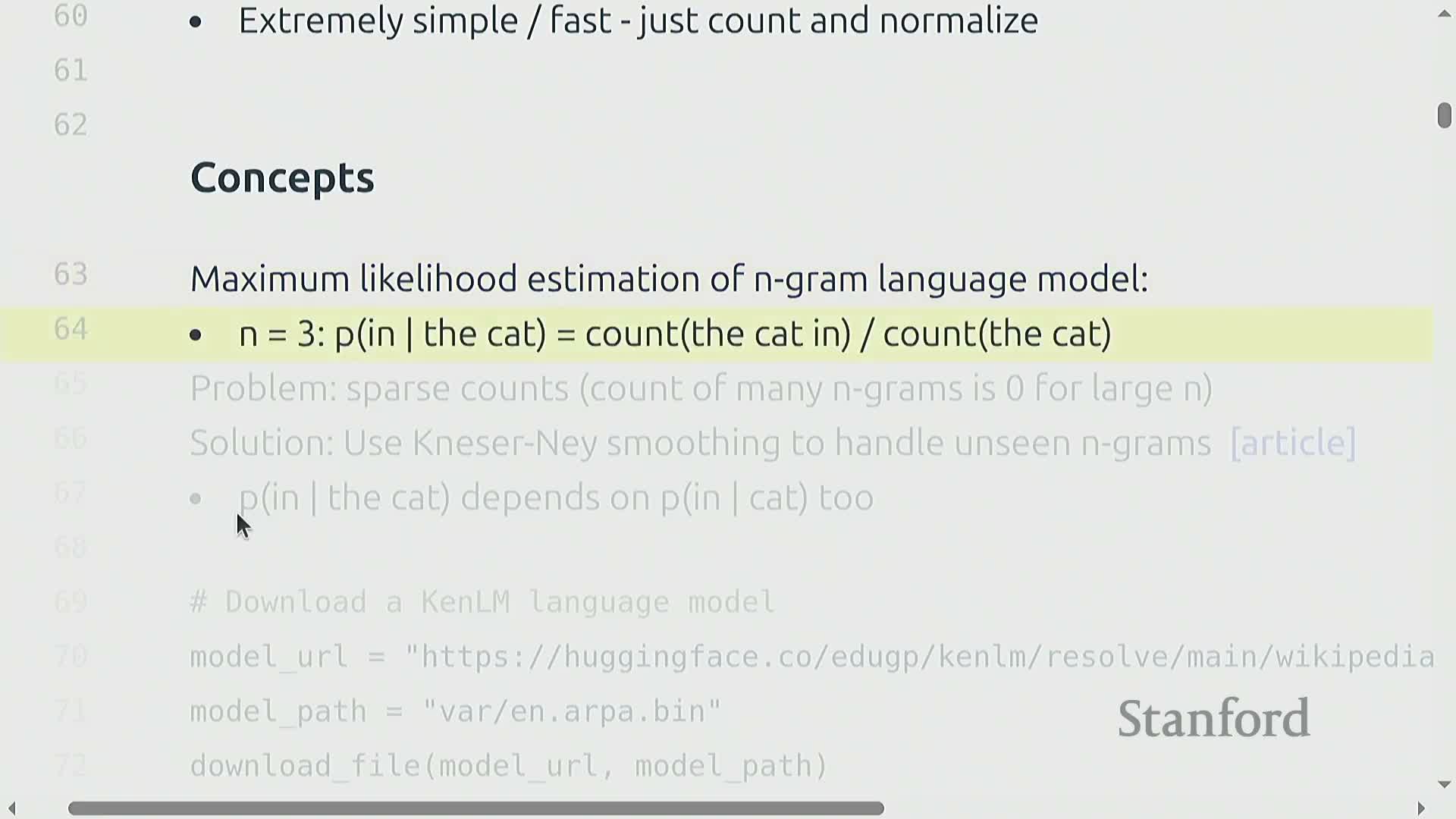

N-gram language models estimate token conditional probabilities by counting n-gram occurrences and normalizing by (n−1)-gram context counts—this yields a maximum likelihood estimate for local sequential structure.

- Count occurrences of each n-gram.

- Divide by the count of the corresponding (n−1)-gram context to obtain the conditional probability.

This is the MLE for short-range dependencies.

Practical implementations use smoothing/backoff or interpolation to address data sparsity as n grows:

- Common techniques include Kneser–Ney and CANLM.

- These methods enable nonzero probability for unseen n-grams by leveraging lower-order statistics (e.g., backing off to smaller n).

Advantages:

- Computationally efficient to train and evaluate relative to large neural models.

- Produce per-document perplexity scores that serve as a proxy for how well data matches a target corpus.

Limitations:

- Myopic locality — evaluates only short contexts, so long-range dependencies are not captured.

- Vulnerable to adversarially constructed high-probability but low-quality examples.

- Reduced expressivity compared with contextual neural models, which can model richer, longer-range structure.

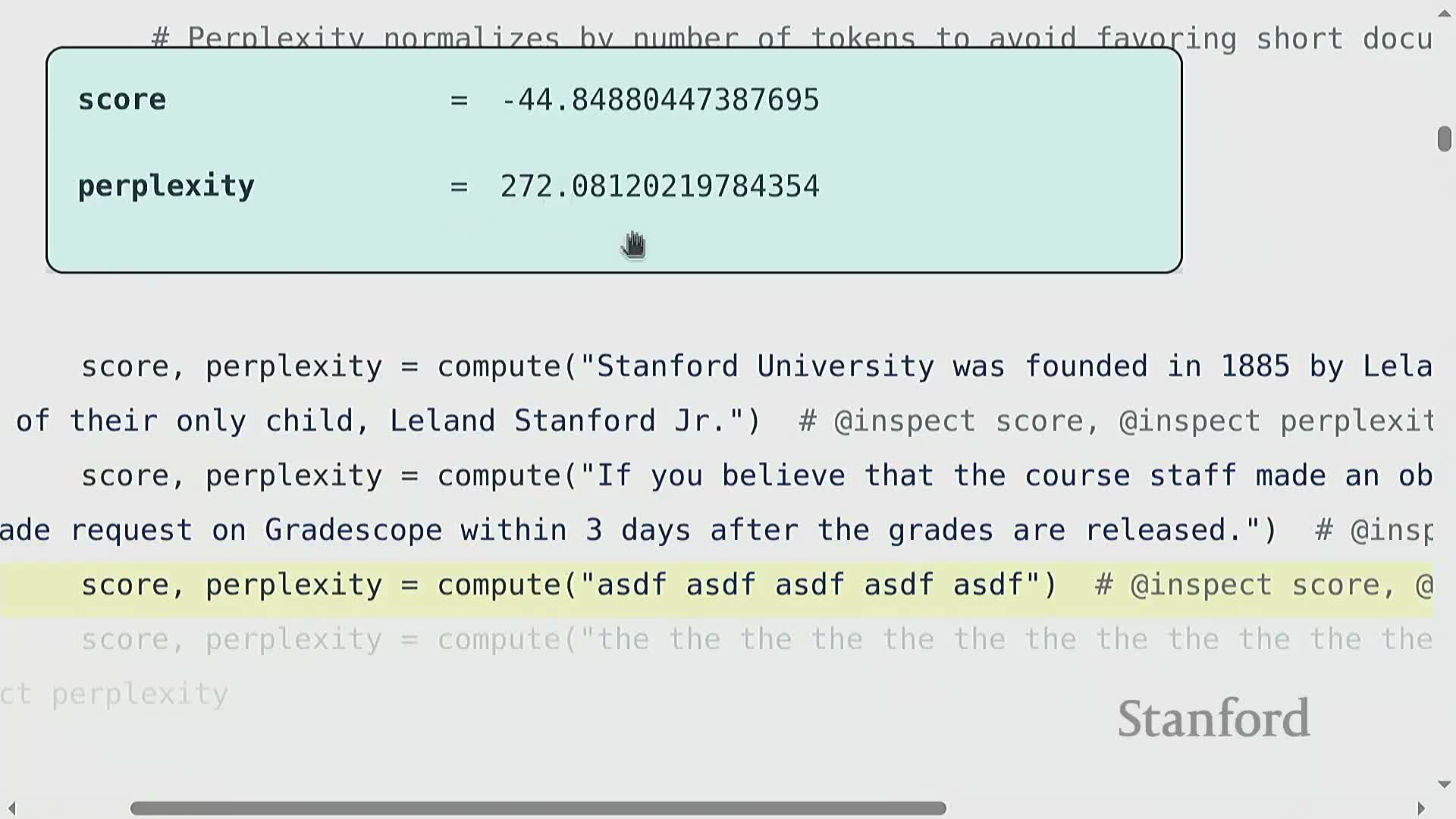

Using n-gram perplexity for dataset filtering (CCNet example)

Perplexity computed from an n-gram model provides a scalar quality score for paragraphs or documents.

Low perplexity indicates a high likelihood under the target distribution and is commonly used to rank raw text data.

A practical pipeline for filtering text by perplexity typically works as follows:

- Score each passage with an n-gram perplexity measure.

- Sort passages by increasing perplexity (lower = better).

- Retain a top fraction of passages (e.g., the top one‑third) as training data or a curated corpus.

This simple heuristic has been effective for creating domain-aligned corpora such as CCNet and early LLaMA training splits.

Example outcomes and caveats:

- Well-formed Wikipedia content generally receives relatively low perplexity.

-

Gibberish or badly formed text typically receives very high perplexity.

- However, there are edge-cases caused by n-gram limitations where scores can mislead (e.g., rare but valid constructions or repeated local patterns).

Practical trade-offs:

- Principal benefit: speed and simplicity — easy to compute at corpus scale and cheap to apply.

- Principal drawback: coarseness and susceptibility to local-context artifacts, which can lead to misranking in some cases.

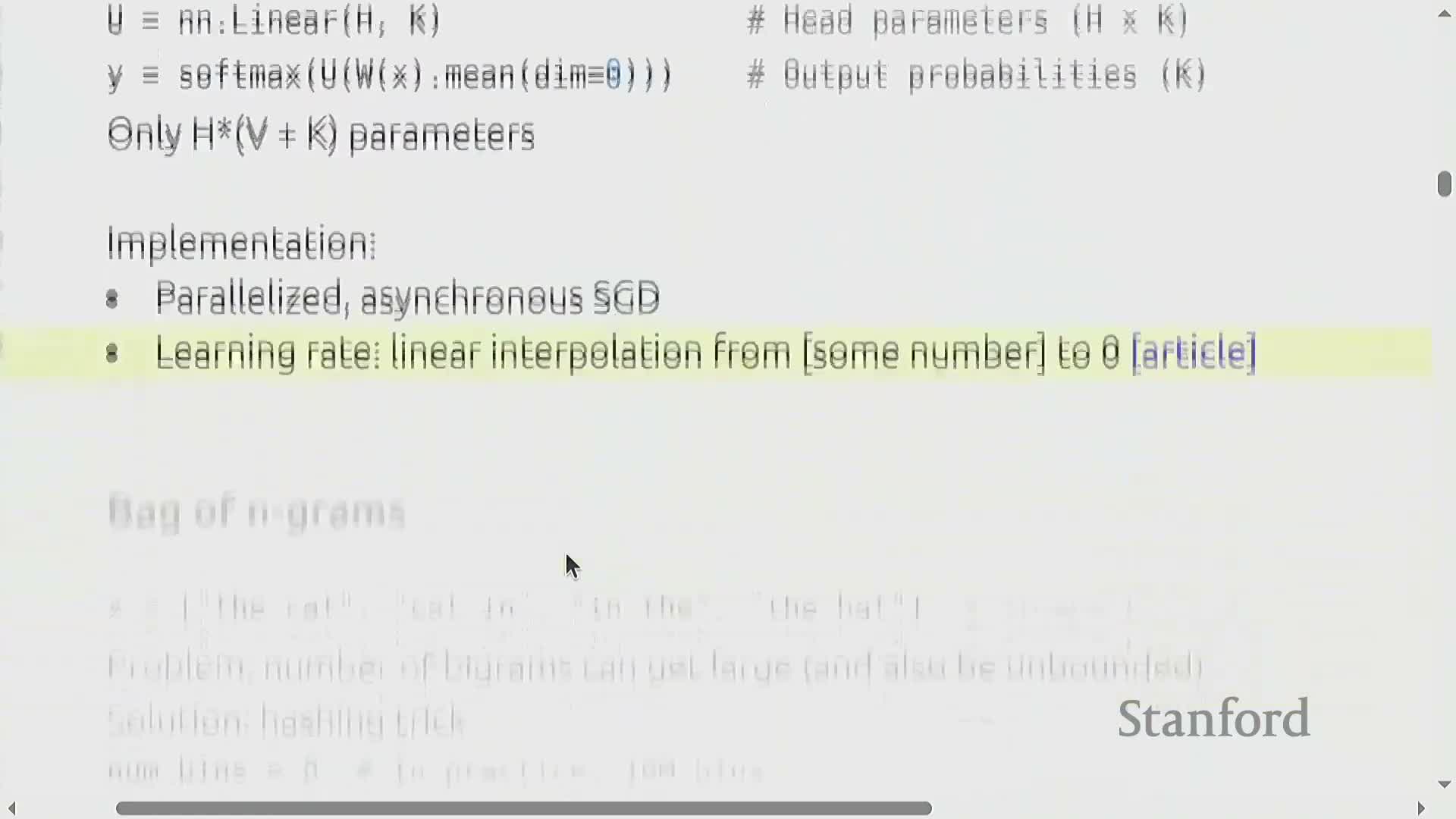

FastText linear classifiers with hashed n-gram features for filtering

FastText implements a near-linear bag-of-(hashed)-n-grams classifier that maps high-dimensional sparse token/ngram feature vectors into a lower-dimensional embedding space, then applies a linear classifier—yielding a fast and memory-efficient text classifier.

-

Hashed n-grams: Hashing n-grams into a fixed number of bins (e.g., 10 million) bounds vocabulary growth and controls model size.

-

Collisions occur, but are often tolerable in aggregate learning and are implicitly handled by optimization.

-

Collisions occur, but are often tolerable in aggregate learning and are implicitly handled by optimization.

-

Embedding + linear classification: The model projects sparse token/ngram features into a compact embedding space and runs a linear classifier from that space, enabling both speed and memory efficiency without storing massive vocabularies.

-

Use cases and scaling: The architecture scales well for binary or multi-class filtering tasks (e.g., language ID, quality, toxicity) and is especially attractive when throughput and resource constraints matter.

-

Expressiveness vs speed trade-off: FastText trades some expressive power for orders-of-magnitude speed improvements compared to deep contextual models.

-

Practical pipeline trade-off: The central decision for filtering pipelines is compute per-example versus selection quality:

-

Faster linear models let you process vastly more raw data for the same compute budget.

-

Larger or deeper models increase per-document cost and may be suboptimal if compute is limited relative to data volume.

-

Faster linear models let you process vastly more raw data for the same compute budget.

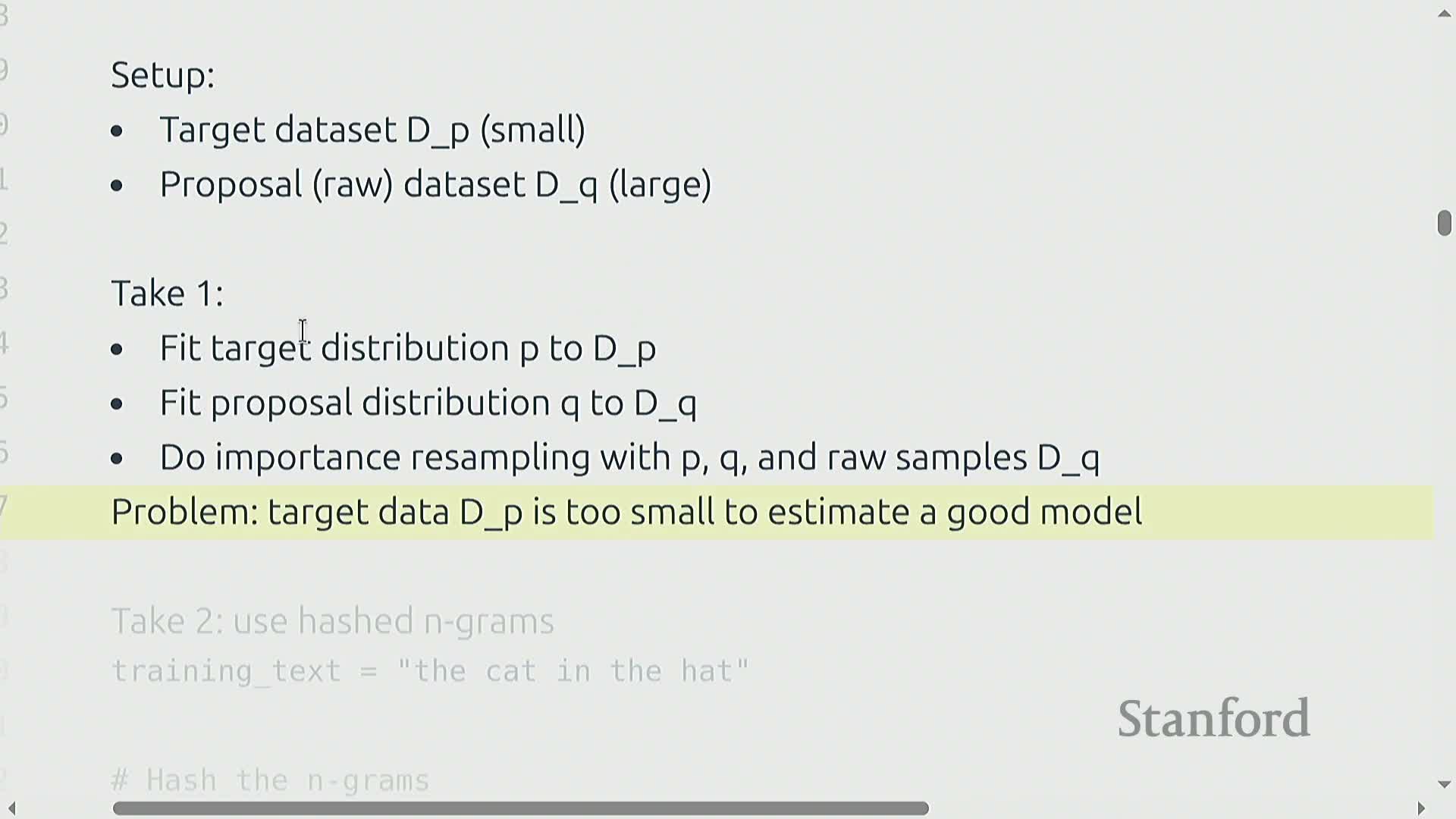

Importance resampling and distributional data selection

Importance resampling treats the target as a distribution P and the raw dataset as a proposal distribution Q, estimating importance weights w(x) = P(x)/Q(x) to resample raw items proportionally to how well they match the target distribution.

When the target dataset is too small to fit a full generative model, lightweight hashed n-gram probability estimators or other tractable density approximations are used to estimate P and Q, producing per-document weights that prioritize diversity and distributional matching rather than binary classification.

How it works (high-level steps):

- Estimate the target density P(x) and the proposal density Q(x) (e.g., with hashed unigram/ngram models or small generative approximations).

- Compute importance weights w(x) = P(x)/Q(x) for each raw item/document.

- Resample items proportionally to those weights to produce a dataset that better matches the target distribution.

Key properties and trade-offs:

- Provides a theoretical grounding for sampling data that matches a desired target distribution.

- Often yields better diversity and smoother distributional matching than discriminative accept/reject classifiers.

- Requires reliable density estimates or approximations; performance depends on the quality of P and Q estimators.

Practical notes:

- Common implementations use hashed unigram/ngram models or small, tractable generative approximations to estimate densities.

- The resulting resampled datasets are typically fed into downstream model training to better align training data with the target distribution.

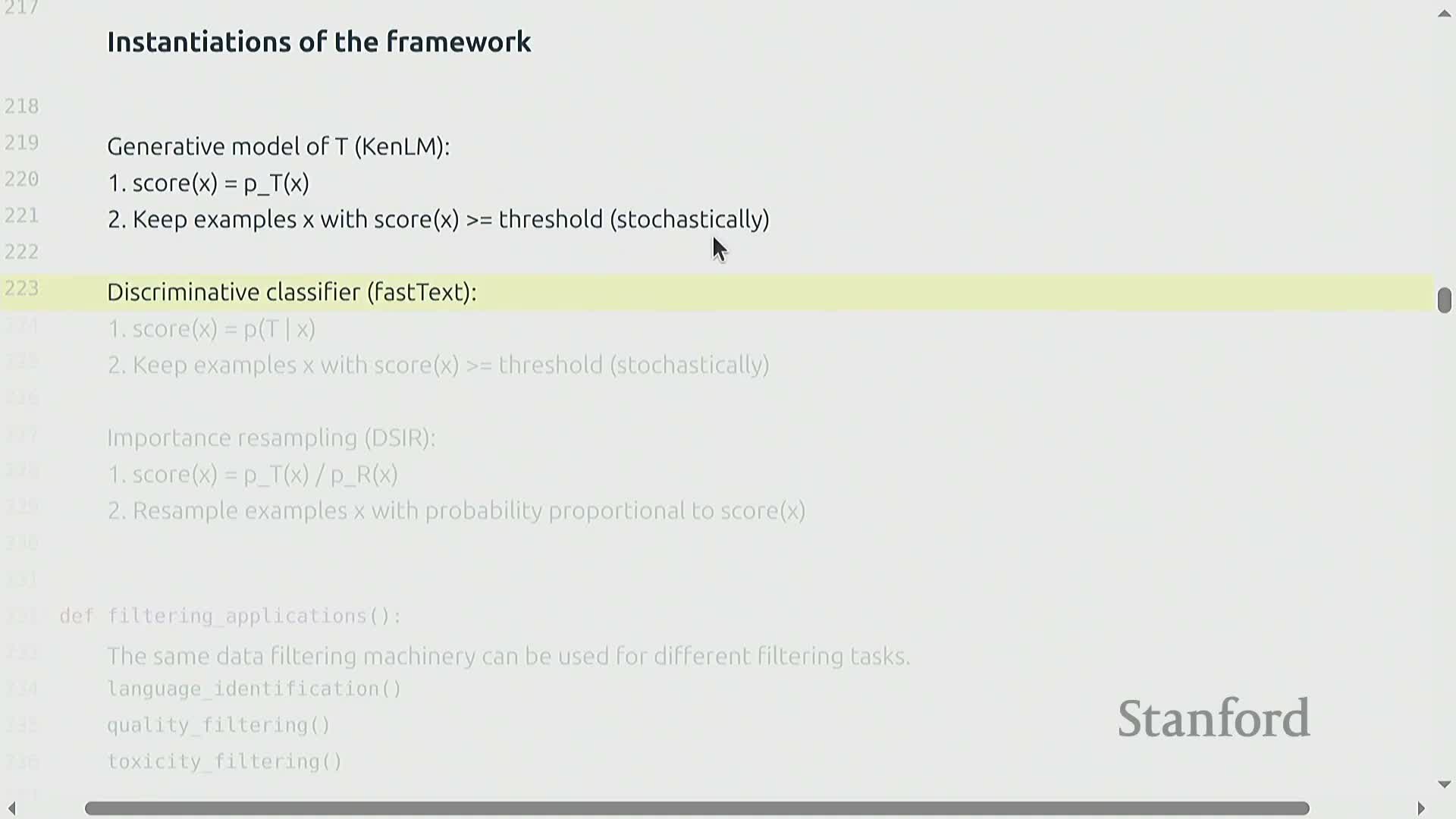

Unified scoring recipe for model-based filtering

All practical filtering approaches share a common pipeline:

-

Estimate models or scoring functions from T and/or R.

-

Compute a per-document score using those models.

-

Retain documents based on a threshold or probabilistic sampling rule to form T’.

Scoring functions can take several forms:

-

Generative — use per-token probability or perplexity as the score.

-

Discriminative — estimate the probability that a sample comes from T rather than R.

-

Importance weights — use the ratio of two generative models.

Each approach produces different trade-offs for diversity and precision.

Thresholding strategies:

-

Deterministic thresholding — apply a fixed cutoff to retain items.

-

Stochastic thresholding — sample around the cutoff to control dataset size and variance.

All methods benefit from improved modeling fidelity (for example, higher-order n-grams or neural models) within available compute constraints.

This abstraction enables interchangeable implementation choices across languages, domains, and quality objectives, while emphasizing scalability and reproducibility.

Limitations of local statistical filters and adversarial risks

Local-context filters, such as n-gram models, primarily evaluate short-range coherence and grammaticality—so they can be gamed by manipulations that preserve local statistics but break overall quality.

- Examples of attacks or failure modes:

- Reorderings that keep n-gram counts but destroy document-level flow

- Paraphrases that change global meaning while retaining local patterns

-

Adversarially constructed sequences that preserve n-gram statistics yet lack global coherence or factual correctness

Increasing n makes these filters more sensitive to larger context, but this comes with clear trade-offs:

- Benefit: better sensitivity to larger context and reduced susceptibility to some local attacks.

- Cost: rapidly increasing sparsity and compute costs as n grows.

By contrast, discriminative classifiers trained on higher-level features or neural representations can capture more semantics and detect issues beyond local patterns.

- Pros: better at modeling document-level meaning and factual inconsistencies

- Cons: substantially costlier to run at web scale and harder to deploy as a first-pass filter

In practice, teams combine these tools pragmatically:

- Use model-based filters (including n-gram checks) to remove gross nonsense and obviously low-quality pages

- Tolerate some residual errors or address them via downstream curation and human evaluation

The engineering posture is a pragmatic trade-off: balance the risks of false accepts and false rejects against available processing capacity and the intended role of the filtered data in training pipelines.

Language identification with FastText for corpus selection

Language identification is a focused application of model-based filtering: a classifier predicts document language and filters raw data to a target language to conserve compute and improve per-language performance.

-

FastText provides pre-trained multi-language classifiers that operate on hashed n-gram features.

- These classifiers produce per-document language probabilities that can be thresholded (e.g., keep English if P(English) > 0.5) to construct monolingual corpora.

Practical workflow:

- Run the classifier to obtain per-document language probabilities.

- Apply a threshold to decide inclusion (example: keep if P(target) > 0.5).

- Add post-processing heuristics and tune thresholds based on sentence length and domain to reduce false positives/negatives.

Challenges and limitations:

-

Short sentences, code-mixed text, dialects, and low-resource languages reduce automatic language ID reliability.

- Thresholds and heuristics must be tuned for sentence length and domain to maintain precision.

Why this matters:

-

Language-specific filtering prevents dilution of the compute budget across unwanted languages.

- It is especially important in compute-limited multilingual training regimes where focusing resources on target languages improves per-language performance.

Domain-specific data curation case study: OpenWebMath

OpenWebMath demonstrates targeted domain curation by treating mathematical writing as a distinct style and building a specialized corpus through a multi-stage pipeline.

-

Rule-based prefilters: apply syntactic heuristics to identify obvious mathematical content.

-

Perplexity-based selection: use a CANLM model trained on a proof dataset (ProofPile) to score documents by how well they fit mathematical language patterns.

-

Discriminative classification: run a FastText classifier trained specifically to identify mathematical text and refine selection.

-

Adaptive thresholds: set different acceptance thresholds depending on whether a document passed the rule-based math identification, yielding stricter or looser inclusion criteria as appropriate.

- These steps combine syntactic heuristics, n-gram density models (via CANLM), and discriminative classification to efficiently gather domain data.

- The result is a curated corpus of high-density mathematical content (e.g., 15 billion tokens) that is highly focused compared with generic web-scale corpora.

Impact and takeaways:

- Training on this targeted corpus yields significant downstream improvements on math-specific tasks compared with training on much larger generic corpora.

- The case illustrates that combining simple heuristics with language-model scoring and fast classifiers can produce data-efficient collections for specialized models.

- Effective domain curation improves sample efficiency and task performance, especially when model capacity and compute are constrained.

Quality filtering strategies and synthetic labeling

Quality filtering is implemented via positive/negative examples drawn from curated sources (positives) and broad web crawl (negatives) to train classifiers that score documents by educational value, textbook-like quality, or topical relevance.

Approaches include:

- Training linear classifiers on high-quality sources (for example, non-CommonCrawl content and Wikipedia-referenced pages).

- Using synthesized labeled sets generated by a strong model (e.g., prompting GPT-4 to label documents) to produce training data for a fast downstream classifier (for example, a random forest on precomputed embeddings).

This is commonly organized as a two-stage distillation process:

- A large model (teacher) labels or ranks documents to produce high-quality semantic labels.

- A lightweight classifier (student) is trained on those labels and precomputed features to enable high-throughput, low-cost inference.

Benefits:

- Enables high-throughput filtering while preserving stronger semantic criteria than simple heuristics.

- Keeps inference costs low by deploying efficient downstream classifiers.

- Empirical results indicate this approach can substantially improve downstream training efficiency and evaluation metrics on specialized tasks compared with unfiltered or naively curated data.

Toxicity filtering with annotated datasets and lightweight classifiers

Toxicity filtering uses curated, labeled datasets to train classifiers that detect unwanted content categories.

- Common datasets: Jigsaw Toxic Comments (and similar curated corpora).

- Typical labeled categories: toxic, severe toxic, obscene, threat, insult, hate speech.

Lightweight classifiers (for example, FastText) are commonly trained on these labels to produce per-document probabilities for each safety-related category—enabling efficient, large-scale screening of web data.

-

Train on curated labeled data to predict the target safety categories and output per-document probability scores.

-

Apply models at scale to remove or downweight content that exceeds predefined thresholds.

-

Mitigate remaining risk by combining automated flags with human review, rule-based checks, and post-hoc mitigation strategies.

Practical deployments usually set conservative thresholds to prioritize reducing unsafe content while acknowledging classifier limitations:

- Classifier imperfections are common on short utterances.

- Performance degrades with ambiguous context.

- Labels and judgments can vary due to cultural variance in annotations.

Overall, toxicity filters are one component of a broader content-safety pipeline and are typically integrated with human oversight, deterministic rules, and additional mitigation layers to achieve robust safety outcomes.

Deduplication: exact and near-duplicate categories and motivations

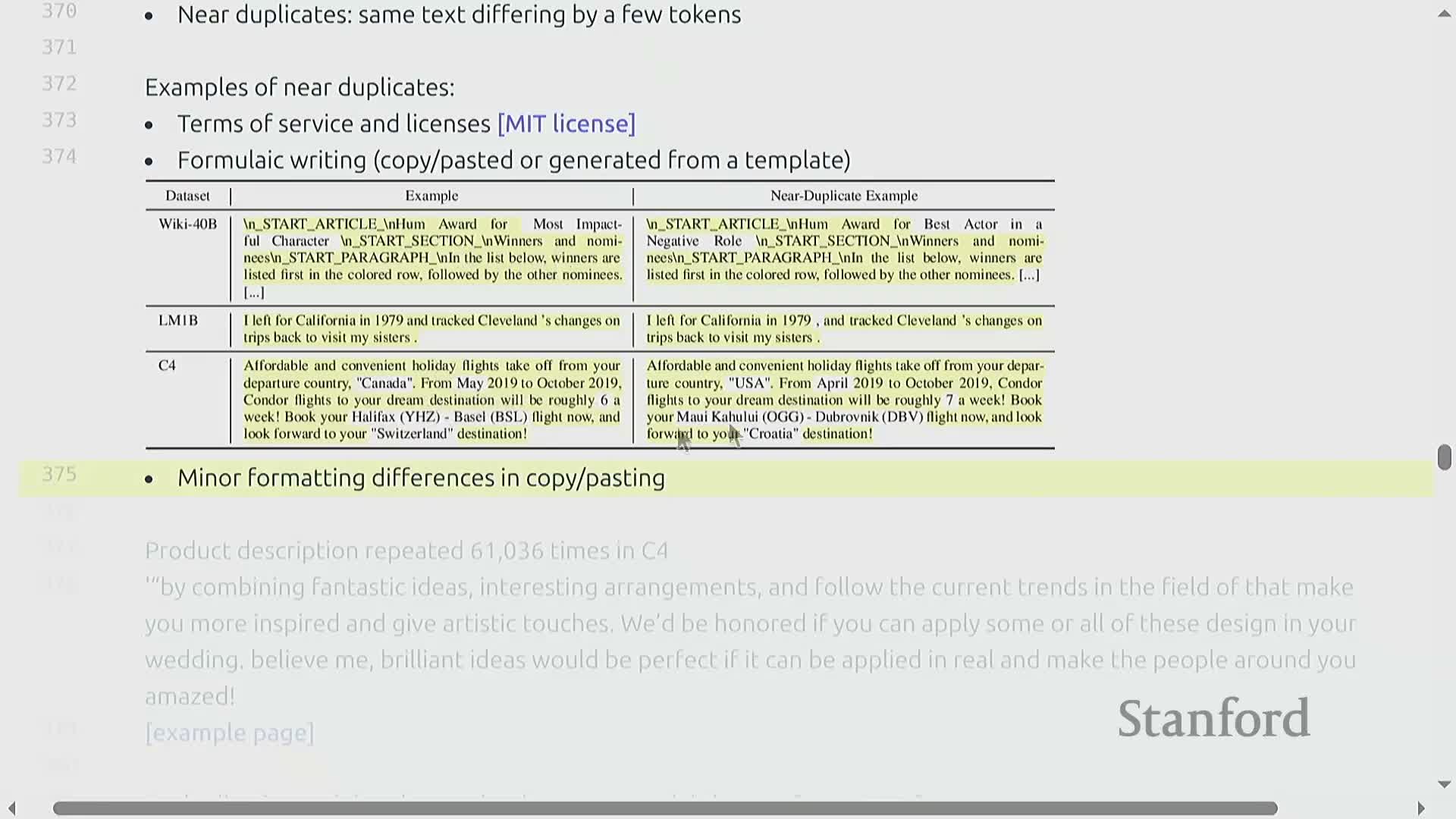

Deduplication addresses both exact duplicates (identical content mirrored across URLs) and near-duplicates (texts differing by a few tokens due to copies, edits, or templating) that otherwise waste training tokens and increase memorization risk.

Exact duplicates often arise from site mirroring and distributed hosting, producing enormous redundant repetition of identical text that distorts sampling during pretraining and overweights repeated content.

Near-duplicates include license text, templated pages, and lightly edited copies — these variations provide little additional signal despite consuming tokens.

Removing or downsampling duplicates improves training efficiency and helps mitigate memorization-related risks (e.g., copyright leakage, privacy), while still allowing sufficient repetition for mid-training regimes where multiple epochs over high-quality sources may be desired.

Key deduplication design choices:

-

Unit of comparison — choose the granularity to compare: sentence, paragraph, or document.

-

Matching criterion — decide between exact match or a similarity threshold for near-duplicate detection.

-

Action — determine the post-match policy: keep one instance, cap counts, or apply other downsampling rules.

Design space and hashing primitives for scalable deduplication

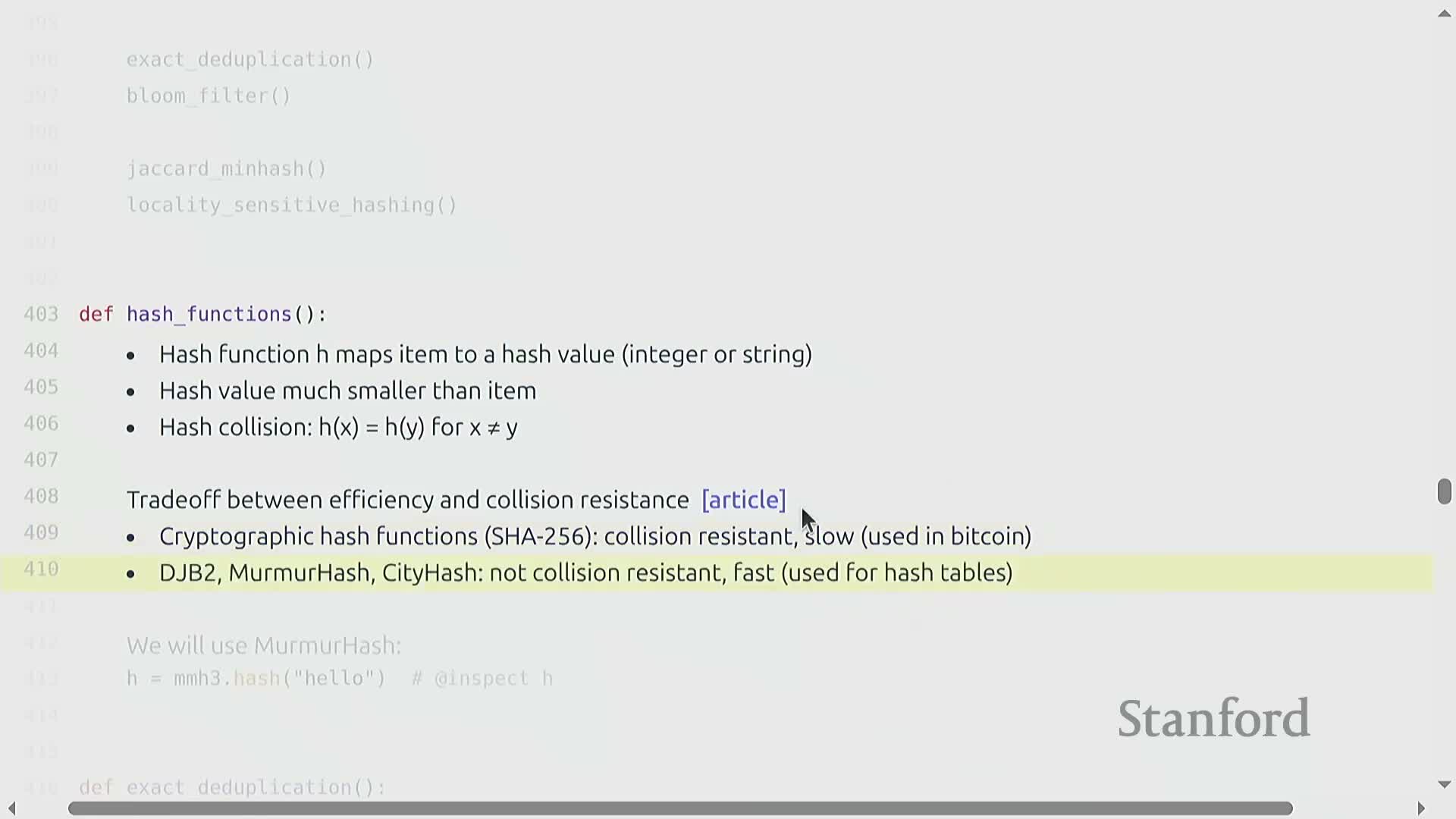

Scalable deduplication requires converting expensive pairwise similarity comparisons into fast unary operations via hashing—hash functions map items to compact values that enable grouping and approximate membership queries instead of performing quadratic pairwise comparisons.

Hash-family tradeoffs:

-

Cryptographic hashes: minimize collision probability but are relatively slow.

-

Non-cryptographic hashes (e.g., MurmurHash): much faster and typically sufficient for large-scale deduplication tasks, at the cost of a higher collision probability.

Exact deduplication pipeline (MapReduce-style):

-

Canonicalize items so equivalent records have the same normalized form.

- Compute a hash for each canonicalized item.

-

Group items into hash bins by their hash value (shuffle stage).

- Keep a single representative per bin (reduce stage).

This yields a high-precision, parallelizable pipeline that is straightforward to implement and memory-efficient.

Limitations:

- This exact, hash-bin approach does not capture near-duplicates that differ by small token edits or by templated substitutions—those cases require fuzzy or locality-sensitive techniques beyond simple hashing.

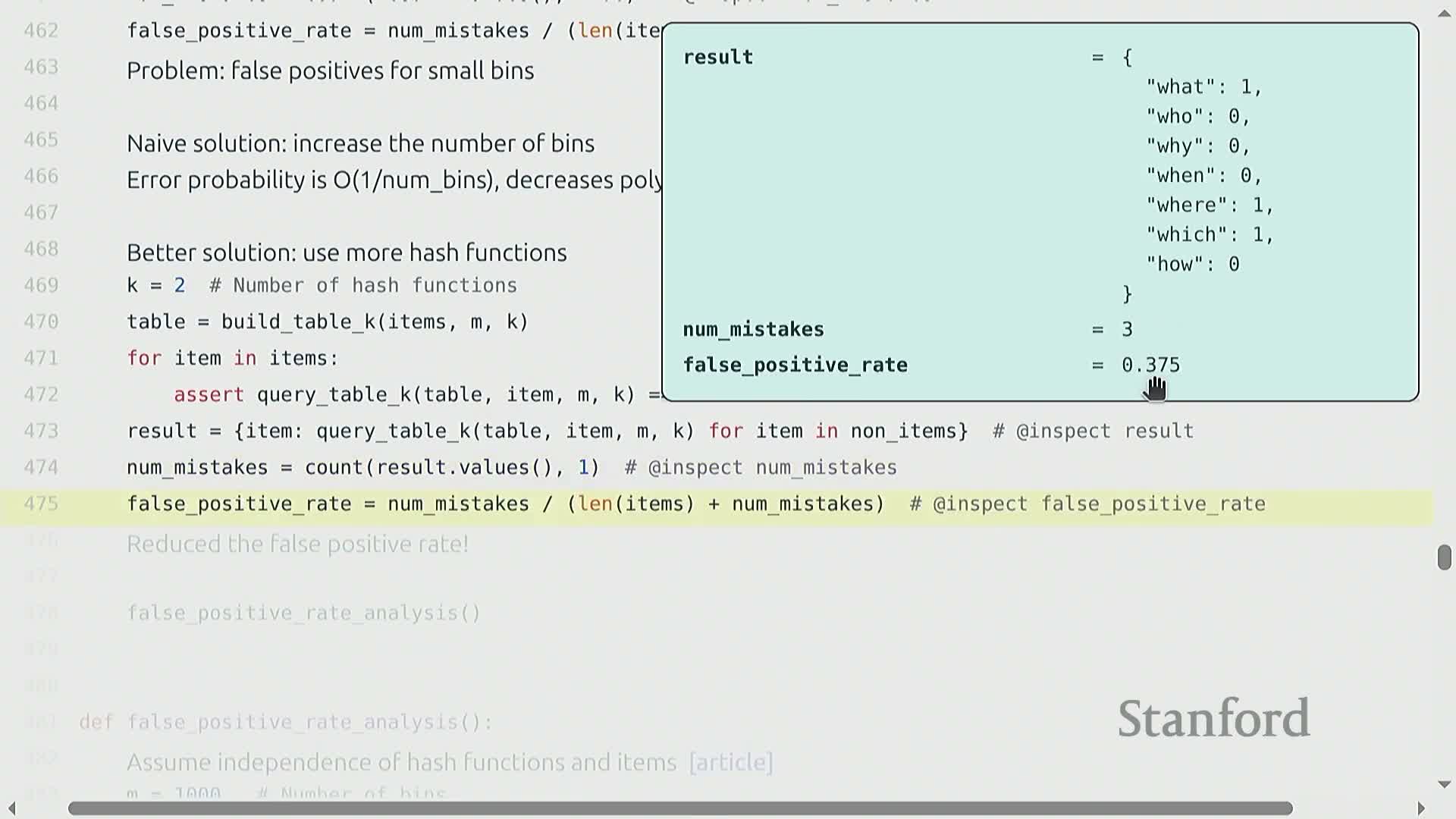

Bloom filter approximate set membership for exact-duplication detection

Bloom filter: a space-efficient probabilistic set representation for answering membership queries with zero false negatives and a controllable false positive rate.

How it works (insertion & query):

-

Insertion: hash each inserted item k times into an m-bit array and set the corresponding bits.

-

Query: check the same k bit positions; if any bit is 0, the answer is definitely “no” (no false negatives). If all are 1, the answer is “yes”, which may be a false positive.

Key properties and trade-offs:

-

False positives occur with probability that depends on m, k, and n (the number of inserted items).

-

Zero false negatives (membership misses do not occur).

- Supports streaming insertion and constant-time membership checks (O(k) hash checks, usually treated as constant).

-

Tunable memory vs. false-positive trade-off: increase m (bits) to reduce false positives, or adjust k to balance rates.

- Widely used for large-scale exact-duplication detection and other applications where occasional false positives are acceptable.

Design guidance:

- Use design formulas and approximations to select m and k for a target false-positive rate given expected dataset size n.

- A common rule-of-thumb for the optimal number of hash functions is k ≈ (m / n) ln 2.

- Choose m (bits) so that, with the optimal k, the false-positive probability meets your target (e.g., 1e-5) given the expected n.

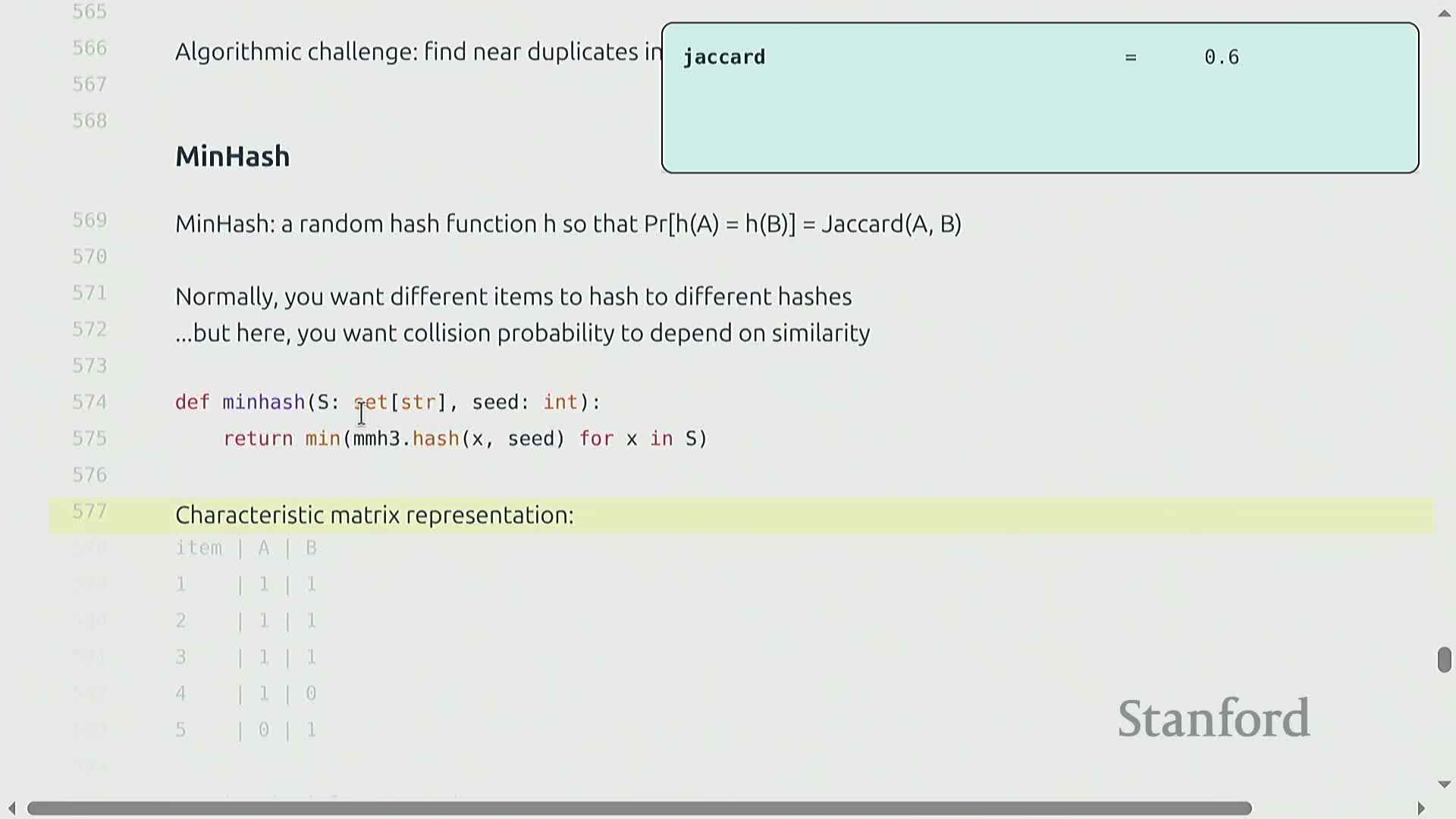

Similarity measures, MinHash and probabilistic reduction of Jaccard

Near-duplicate detection uses set similarity measures such as the Jaccard index (|A ∩ B| / |A ∪ B|).

A probabilistic reduction to unary sketches is provided by MinHash: repeated independent applications of a randomized hash family map a set to its minimum hashed element, and the resulting collision probability equals the Jaccard similarity between the original sets.

-

Constructing a MinHash sketch:

- Choose k independent randomized hash functions from a hash family.

- For each hash, map the set to the element with the minimum hash value.

- Collect the k minima into a k‑coordinate sketch (k scalar values).

- Choose k independent randomized hash functions from a hash family.

- The fraction of matching coordinates between two MinHash sketches estimates the Jaccard similarity.

-

That estimator is unbiased and has a known variance, so accuracy improves predictably with k.

- Practical implications:

-

Compact representation: sets are compressed into k scalars rather than full pairwise comparisons.

-

Linear-time sketching: large corpora can be sketched in time proportional to the data size.

-

Cheap comparisons: sketches can be compared quickly, forming the basis for scalable near-duplicate pipelines that avoid O(N^2) pairwise comparisons.

-

Compact representation: sets are compressed into k scalars rather than full pairwise comparisons.

MinHash is particularly effective for bag-of-shingled representations (token n-grams) that capture surface similarity between documents.

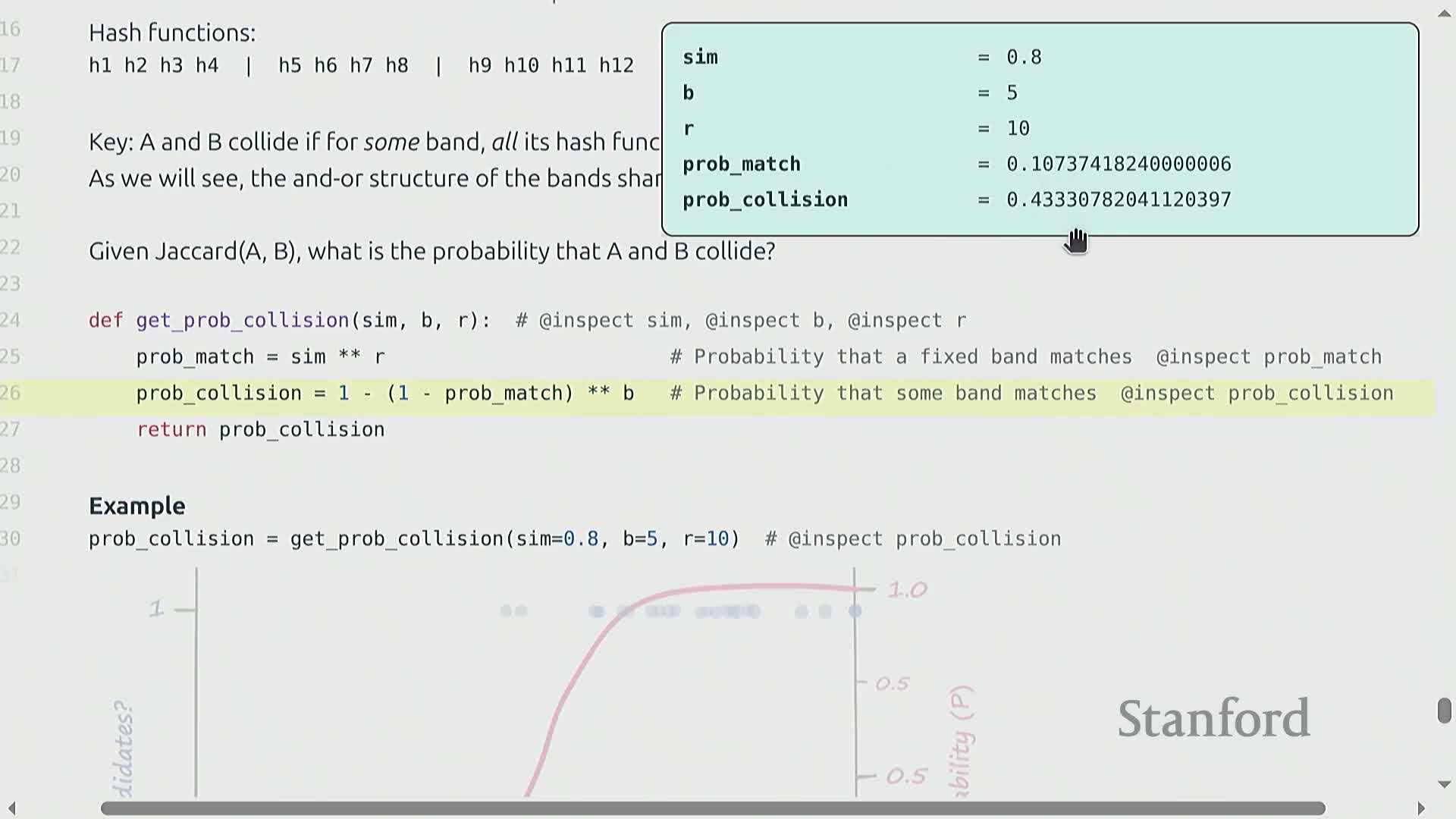

Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) with banding to amplify thresholds

Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) sharpens MinHash collisions into a practical approximate neighbor-retrieval rule by partitioning k MinHash values into B bands of R hashes each and declaring a candidate match if any band is identical between two items.

The banding construction yields a tunable, sigmoid-like mapping from true similarity to collision probability:

- Increasing R makes band equality rarer — the curve shifts right and sharpens (higher selectivity).

- Increasing B raises the chance of at least one band match — the curve shifts left (higher sensitivity).

By selecting B and R appropriately you can concentrate collision probability around a chosen similarity threshold so that pairs above the threshold are very likely to be retrieved and pairs below are unlikely.

Typical retrieval workflow (sublinear via hash tables):

- Compute k MinHash signatures for each item.

- Partition the signature into B bands of R hashes.

- Hash each band into a hash table (band signature → bucket).

- At query time, probe the band hash tables and union candidates from matching buckets; then verify candidates as needed.

Practical pipelines use large k and tune B/R to match application-specific near-duplicate criteria (for example, ~0.99 Jaccard for strict paragraph deduplication), accepting probabilistic retrieval guarantees and trading off recall versus precision when choosing parameters.

Practical considerations: embeddings for paraphrase-sensitive deduplication and duplicate handling policies

Paraphrase- or semantics-sensitive deduplication requires dense embeddings and approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search rather than surface n-gram methods like Jaccard/MinHash—this enables detection of semantically similar paraphrases but comes with higher computational cost for embedding generation and index maintenance.

Embedding-based LSH or ANN structures fit into the same high-level framework as MinHash LSH: compute a vector per document, then index/query to find neighbors above a similarity threshold. Key components and steps are:

-

Vectorize each document into a dense embedding (semantic representation).

-

Build an index using methods such as product quantization, HNSW, or LSH to support fast neighbor queries.

-

Query for neighbors using a similarity metric (e.g., cosine similarity) and a chosen threshold to detect paraphrases/near-duplicates.

-

Tune hyperparameters (index size, PQ/graph settings, LSH bands, threshold) to trade recall for efficiency and storage costs.

Policy choices about what to do with detected duplicates are important and depend on objectives:

-

Full deduplication: remove all duplicates to maximize dataset uniqueness and reduce memorization risk.

-

Retain multiple occurrences: keep repeats when the source is genuinely high-quality or when multi-epoch training over the same data is desired.

-

Count-capping heuristics: instead of full elimination, apply caps (e.g., sqrt or log scaling of counts) to preserve useful signal while avoiding extreme overrepresentation.

These design choices balance three main concerns:

-

Dataset diversity (favoring deduplication),

-

Memorization risk (favoring stricter deduplication), and

- The intended training regimen (e.g., single-pass pretraining vs. multi-epoch fine-tuning), which may justify retaining some duplicates.

Choose the embedding model, indexing method, similarity threshold, and deduplication policy together to meet your target trade-offs in quality, compute, and risk.

Lecture summary and next steps

The lecture consolidates algorithmic primitives for preparing training corpora:

-

n-gram models

-

fast linear classifiers

-

importance resampling for filtering

-

Hashing-based techniques for deduplication, including:

-

exact hashing

-

Bloom filters

-

MinHash

-

LSH (Locality-Sensitive Hashing)

-

exact hashing

Each primitive is characterized by three complementary aspects:

-

Computational cost — runtime, memory, and scalability trade-offs

-

Statistical properties — bias, variance, and impact on distributional fidelity

-

Practical role — how the primitive contributes to extracting a high-quality target dataset from raw web data

Practical pipelines combine these methods to perform concrete corpus-preparation tasks:

-

Language identification — filter and route data by language

-

Quality and toxicity filtering — remove low-quality or harmful content

-

Targeted domain curation — select domain-specific subsets from broad web crawls

-

Exact and near-duplicate removal — eliminate redundant content using hashing and similarity techniques

-

Parameter tuning is applied across the pipeline to balance false-positive vs. recall and to meet compute constraints (e.g., memory, throughput).

The next instructional unit transitions to reinforcement learning and alignment topics.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: