CS336 Lecture 16 - Alignment - RL

- Lecture overview and goals

- RLHF formulates post-training as optimizing a policy using pairwise human preference data

- DPO updates increase likelihood of preferred responses while regularizing toward a reference policy

- DPO variants modify normalization and reference usage to address practical issues

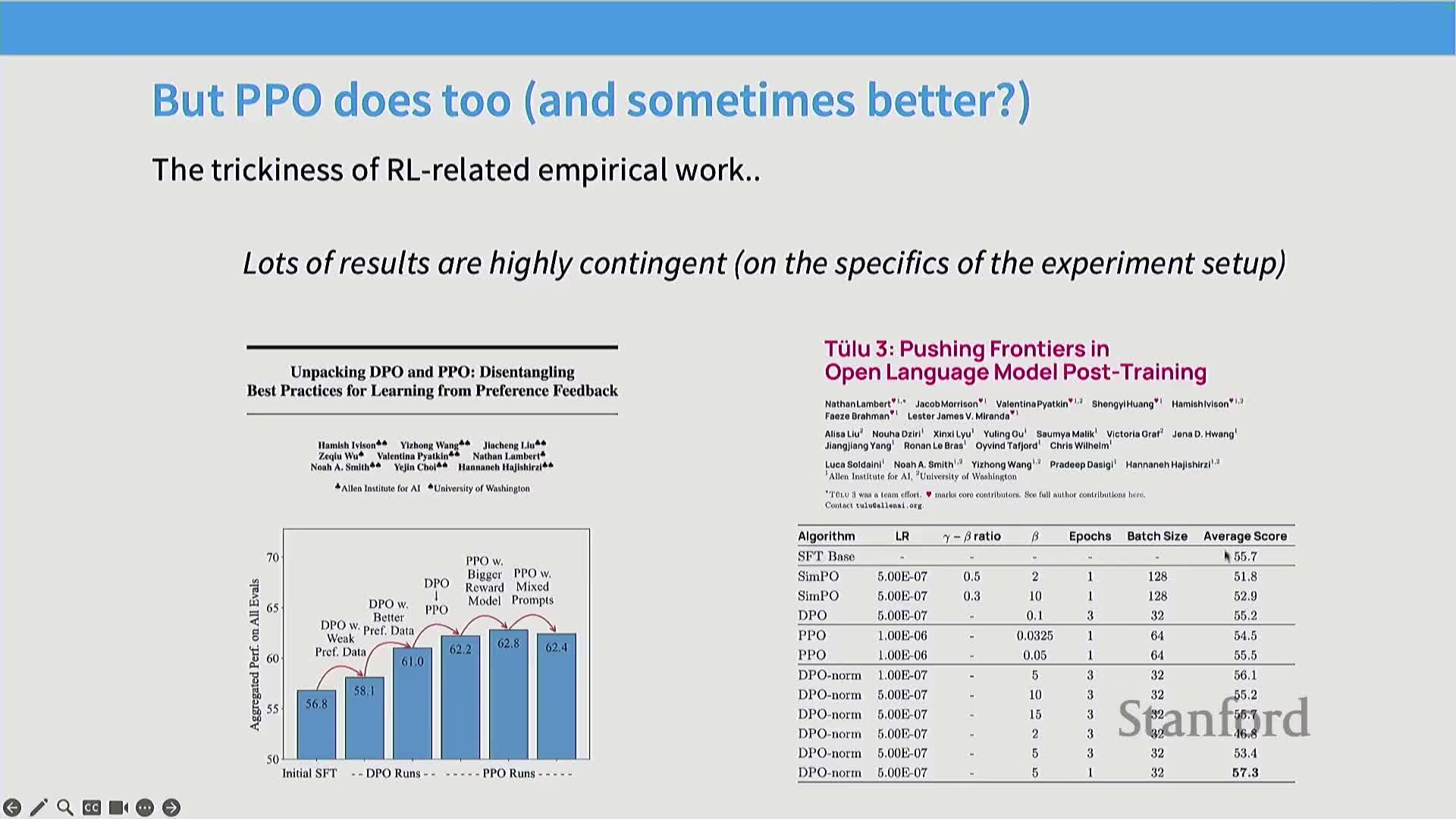

- RLHF empirical findings depend strongly on dataset, environment, and base model

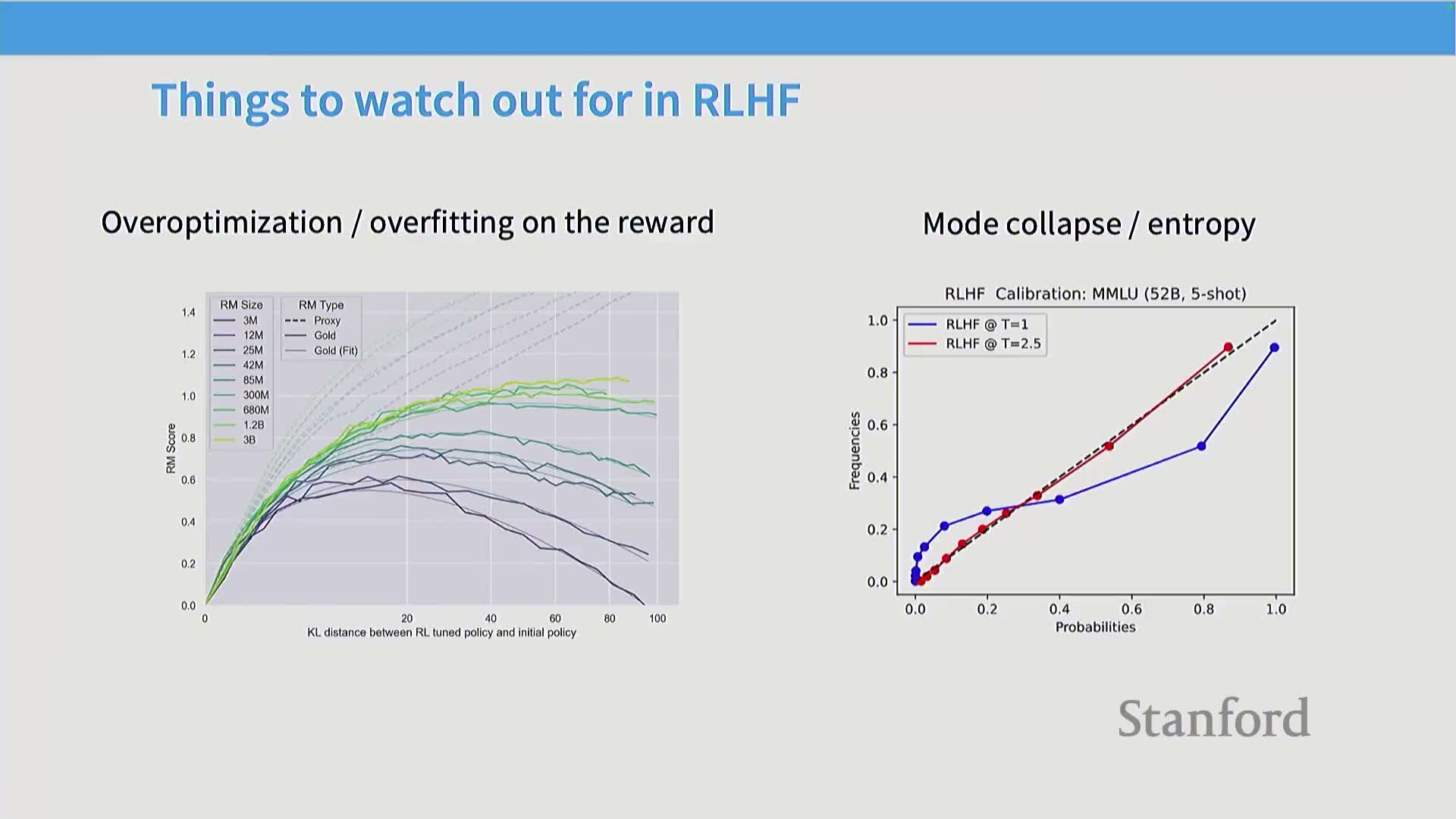

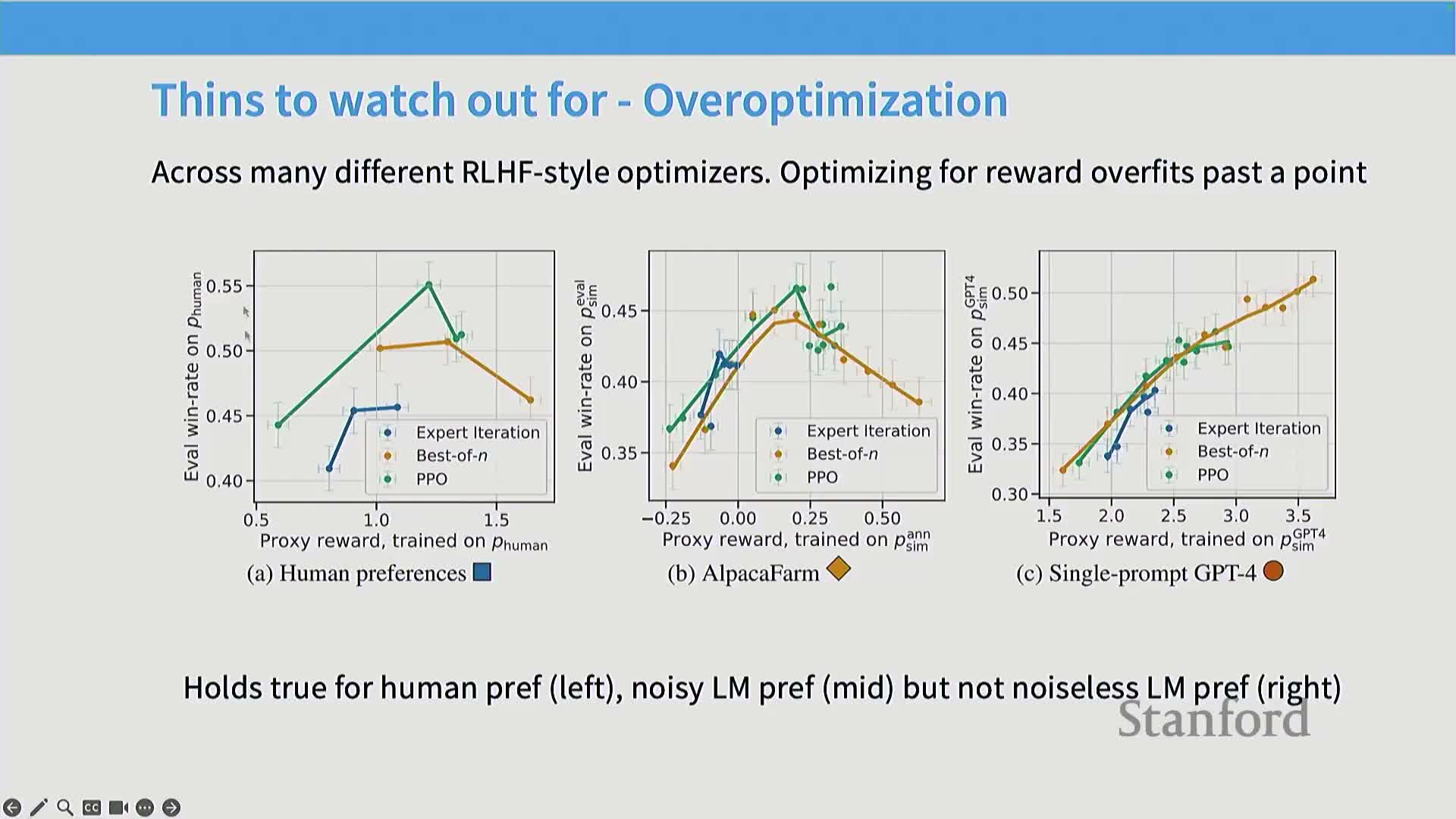

- Overoptimization (reward hacking) causes proxy-reward gains to diverge from true human preferences

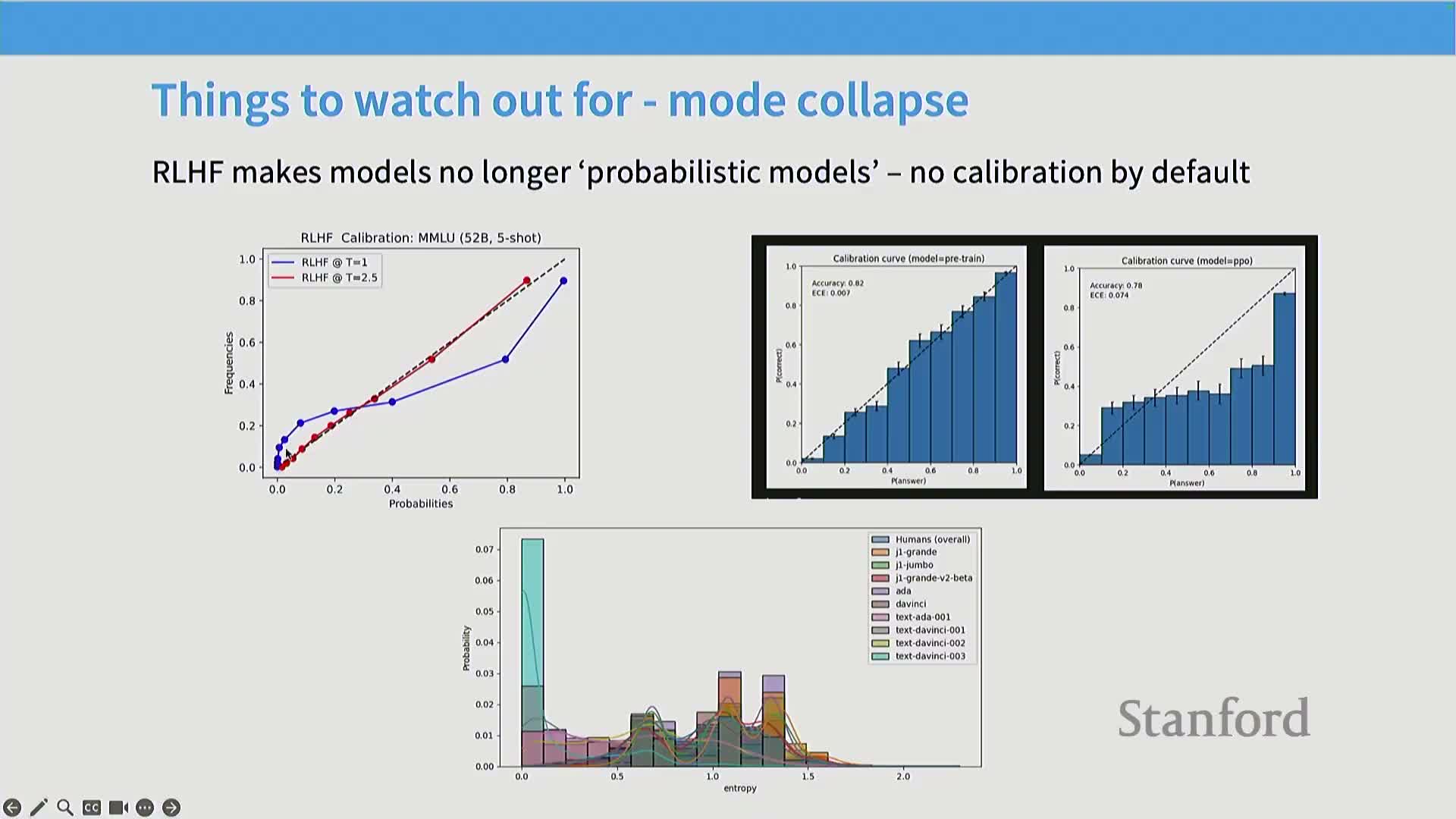

- RL-trained policies often exhibit reduced probabilistic calibration and increased overconfidence

- Proxy vs true reward axes and train-test gaps in reward-model optimization

- Verifiable rewards enable scalable RL by using fast, testable objectives instead of noisy human feedback

- Policy-gradient foundations, TRPO/PPO, and the cost of rollouts

- PPO implementations need auxiliary components: value nets, advantage estimation, reward shaping, and careful rollout handling

- Generalized advantage estimation (GAE) trades bias and variance and can be simplified in practice

- GRPO replaces value-based advantage estimation with a group-based z-score baseline to remove the need for a value network

- Per-prompt grouping normalizes for question difficulty and enables variance reduction without cross-question interaction

- GRPO training loop is simple: compute per-group normalized advantages, add KL regularization, and backpropagate with numerical safeguards

- GRPO produces empirical gains on reasoning tasks relative to simple fine-tuning baselines

- Dividing advantages by group standard deviation and length normalization introduce theoretical violations and biases

- Removing std-scaling and fixing length normalization stabilizes outputs and removes pathological incentives

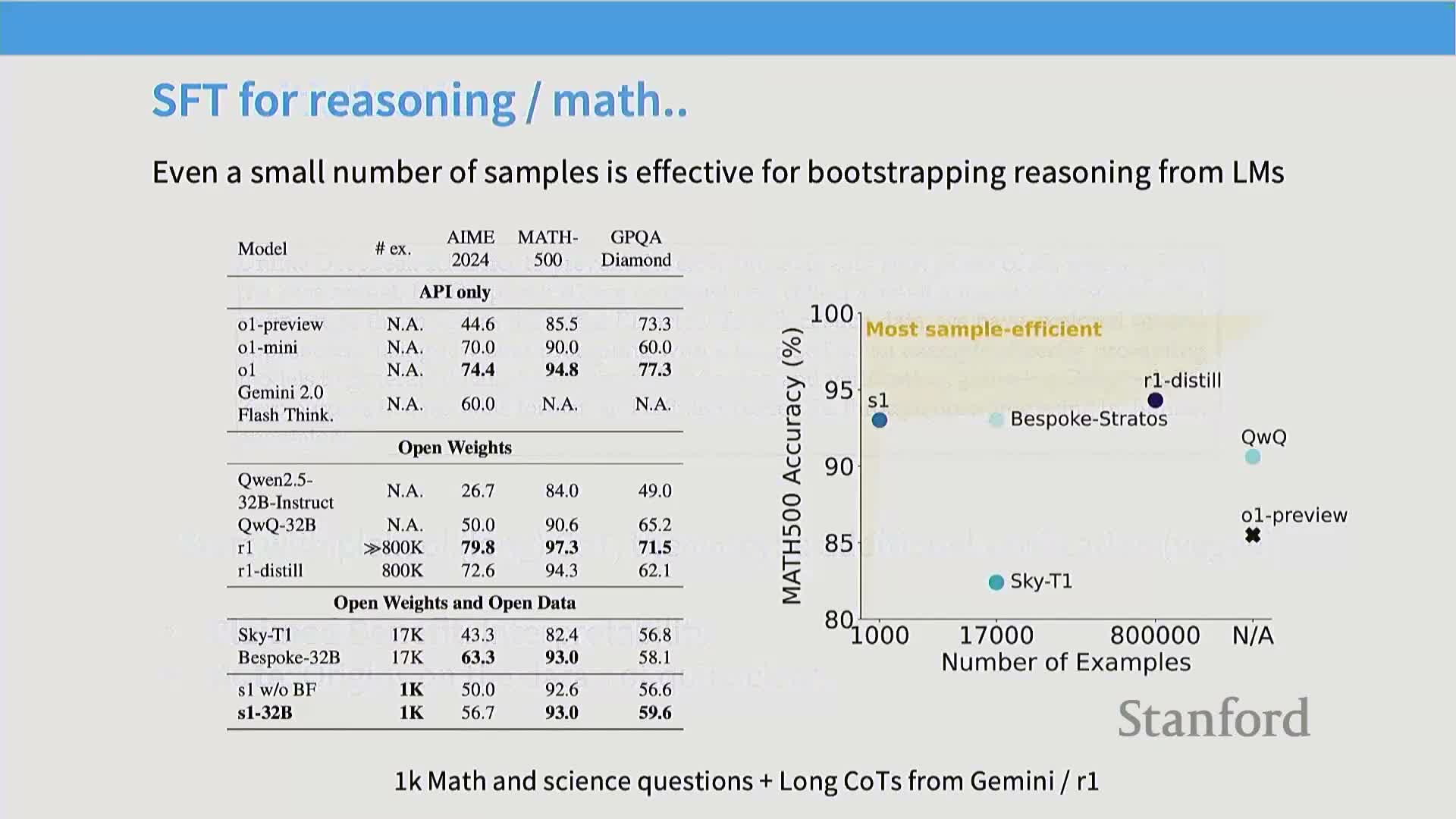

- Contemporary reasoning-model pipelines commonly combine SFT initialization, reasoning RL on verifiable rewards, and later RLHF/distillation

- R1 demonstrated that outcome-based GRPO on math tasks can replicate large-model reasoning performance with a simple pipeline

- R1 results emphasize SFT initialization, language-consistency rewards, and that PRMs/MCTS delivered limited practical benefit

- K1.5 matched or exceeded prior reasoning baselines by combining curated verifiable data, a GRPO-like RL algorithm, and a length-compression reward

- Distributed RL at scale requires separating inference and training workers, careful weight synchronization, and handling variable-length CoTs

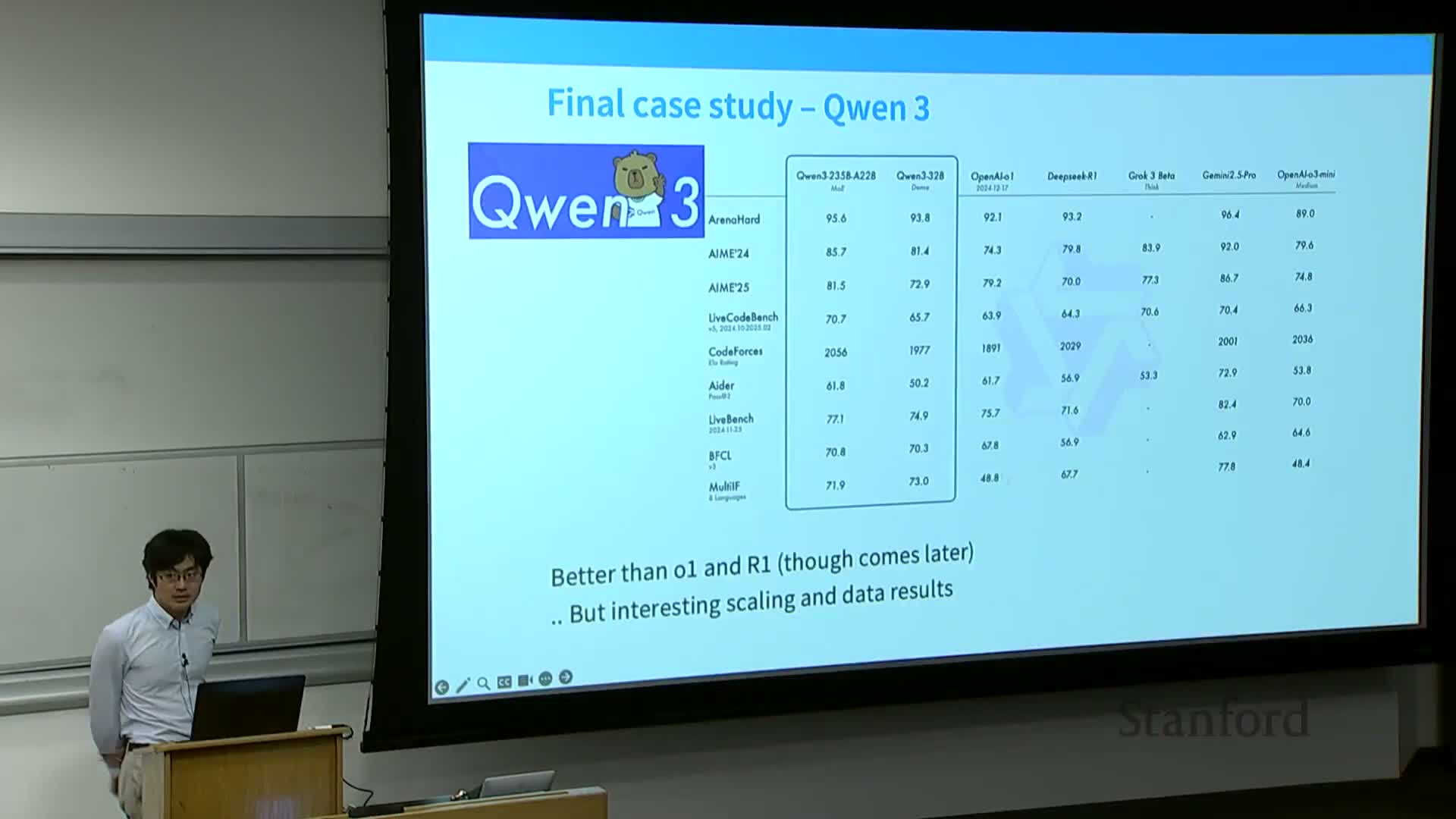

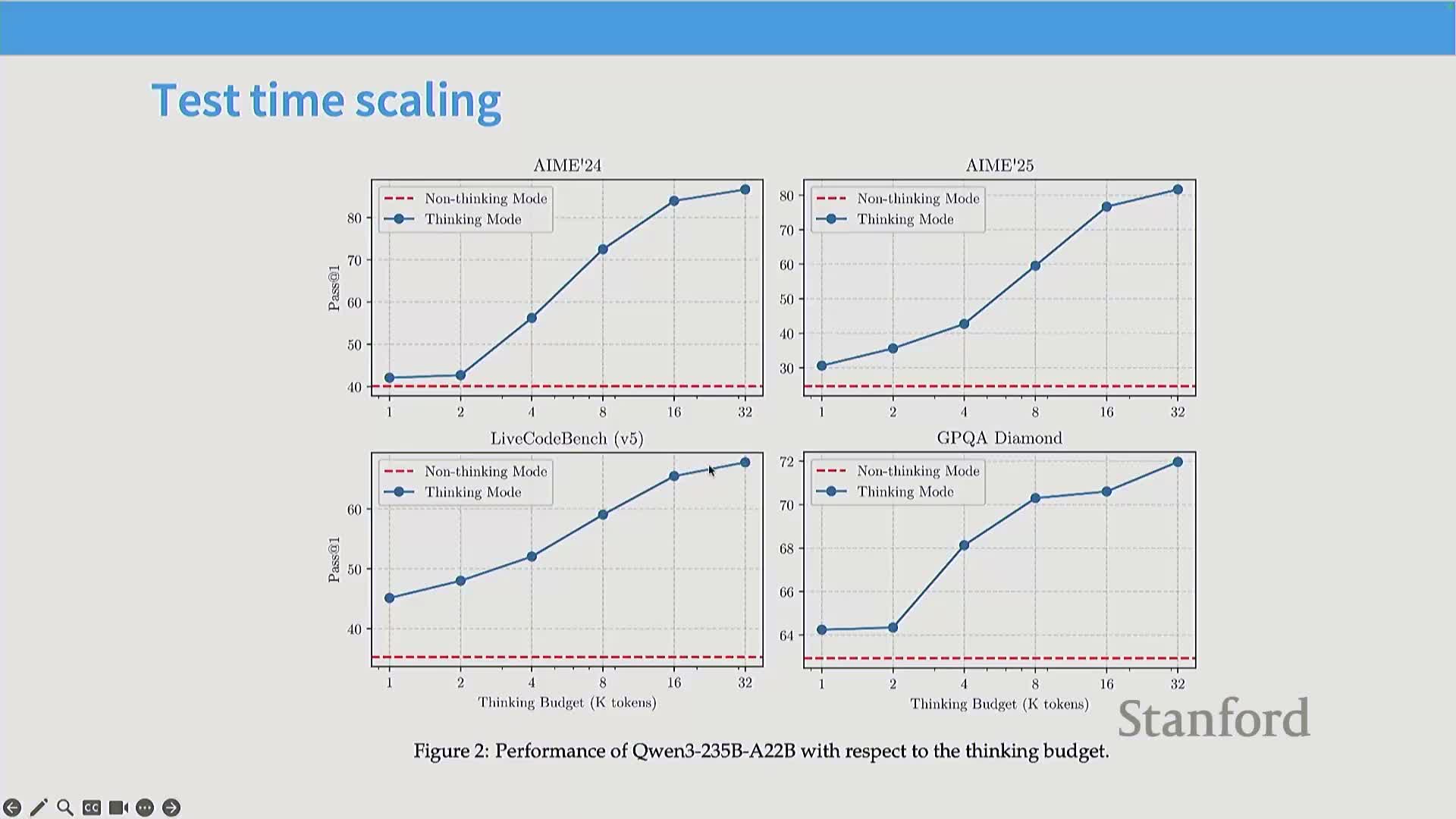

- Qwen 3 adds thinking-mode fusion to let a single model switch between thinking and immediate-answer modes, enabling runtime control of chain-of-thought length

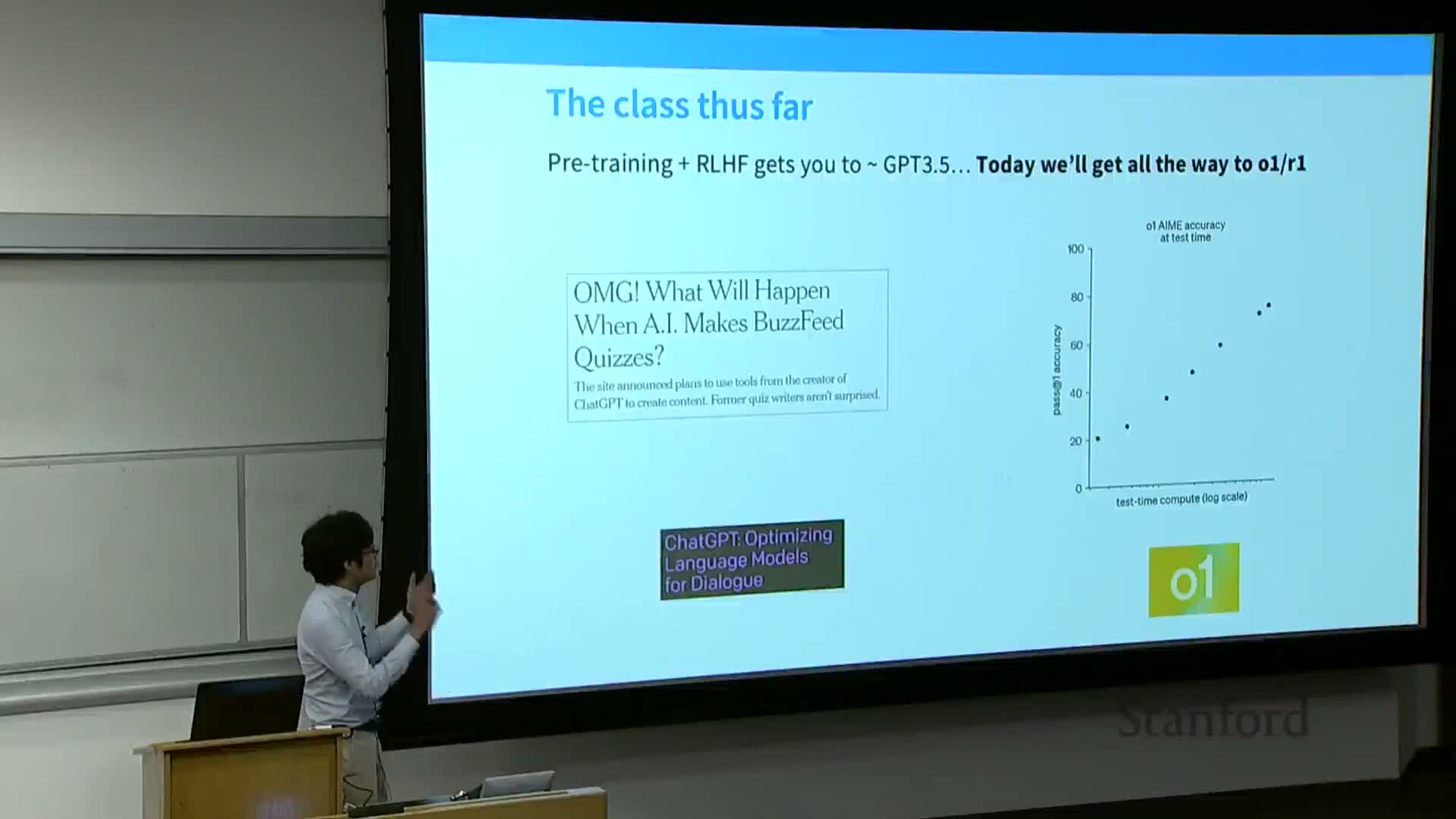

Lecture overview and goals

The lecture finishes the RLHF (Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback) material and introduces reinforcement learning from verifiable rewards for reasoning models.

It frames verifiable-reward RL as a scalable alternative to noisy pairwise human-preference optimization and previews two parts of the session:

- an algorithmic section that develops methods for verifiable-reward RL, and

- a set of case studies showing how those algorithms behave in practice.

The framing emphasizes why moving beyond pairwise human feedback matters for current large-model reasoning advances: verifiable rewards enable larger-scale, less noisy optimization that can better drive reasoning improvements.

The remainder of the talk first recaps RLHF basics and then develops concrete algorithms and empirical recipes for verifiable-reward RL.

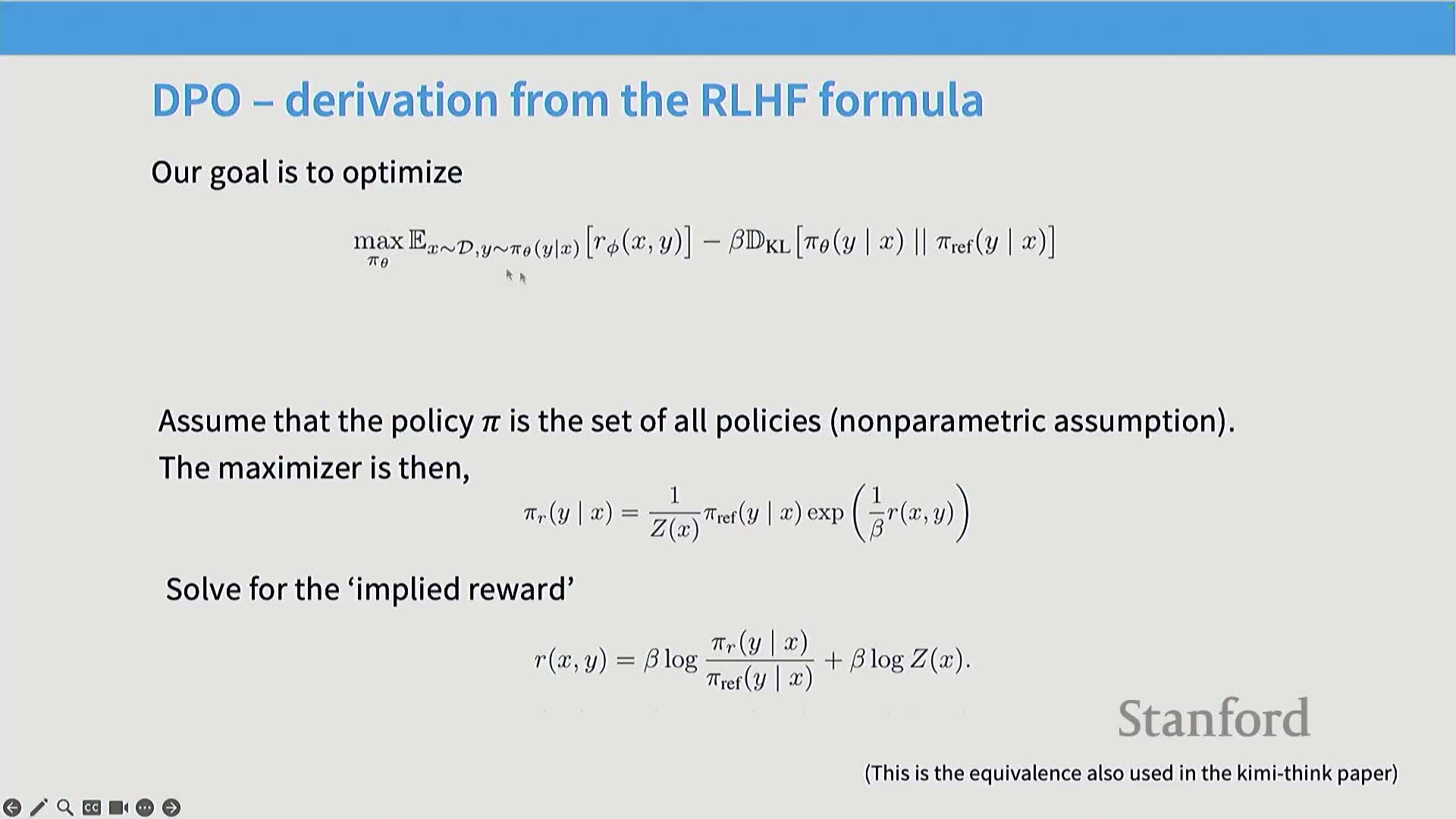

RLHF formulates post-training as optimizing a policy using pairwise human preference data

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) treats observed pairwise preference comparisons as the supervisory signal and seeks a language-model policy that maximizes the underlying reward implied by those preferences.

Key challenges and ideas:

- The policy appears inside expectations because samples are generated by the model, so standard supervised likelihood training does not apply directly.

- Methods such as Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) reparameterize the problem by making a nonparametric assumption on the policy class and expressing the reward in terms of policy ratios.

- Those ratios are plugged into a Bradley–Terry preference likelihood, producing a supervised-style objective that is compatible with gradient-based training.

This reparameterization converts preference optimization into an alternative supervised optimization target while preserving the preference information from pairwise comparisons.

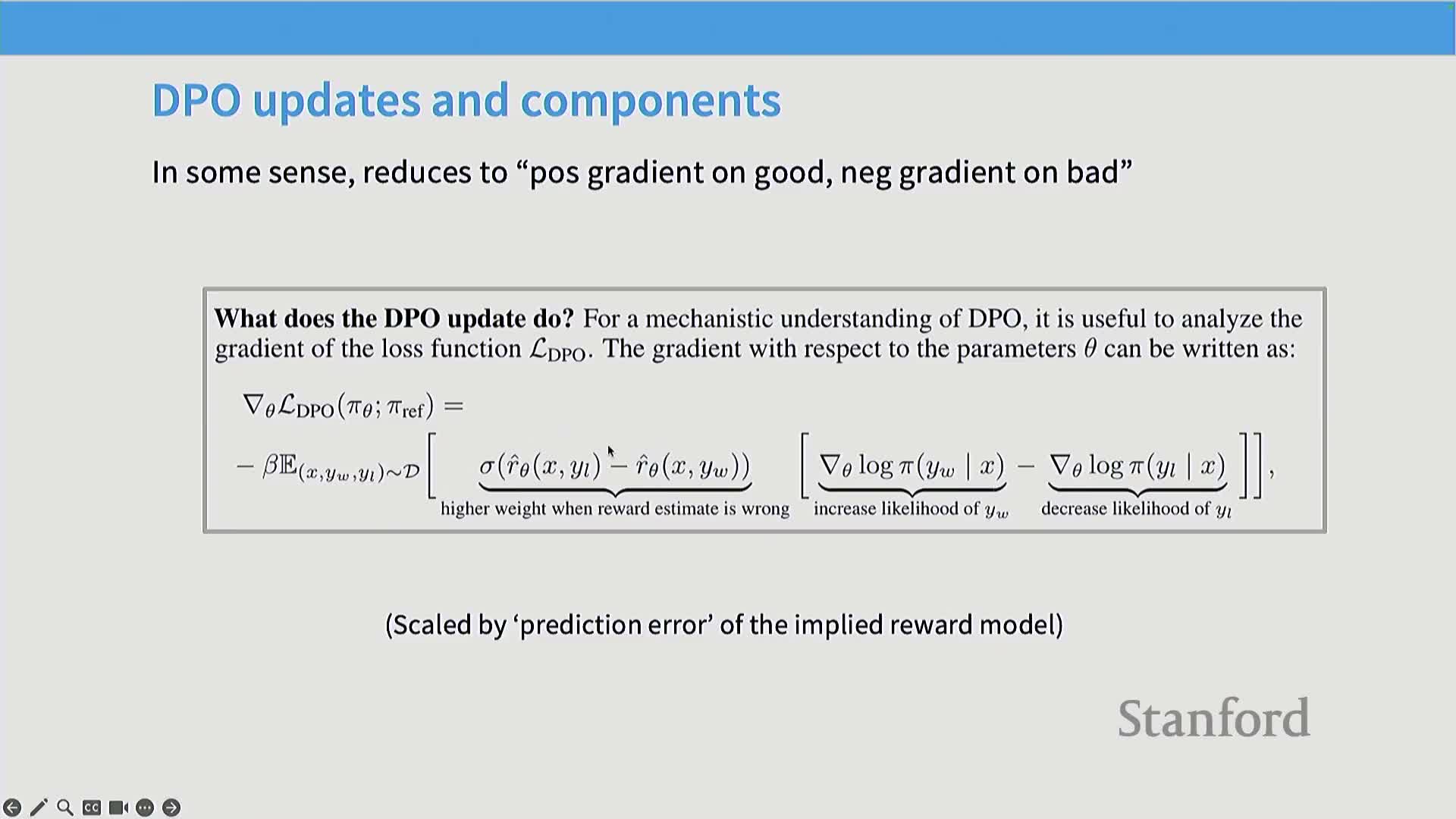

DPO updates increase likelihood of preferred responses while regularizing toward a reference policy

Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) implements updates that increase the likelihood of preferred responses and decrease the likelihood of less-preferred ones.

Important mechanics and properties:

- A multiplicative regularization coefficient (commonly beta) controls divergence from a reference policy.

- Gradient steps weight updates more strongly when reward estimates are uncertain or incorrect, explicitly pushing probability mass toward better-ranked sequences and away from worse-ranked ones.

- DPO’s update has a simple supervised-like form, avoiding many complexities of on-policy RL and making it easy to implement.

Practical appeal:

- Empirically attractive because of implementation simplicity and stable behavior relative to many classical RL algorithms.

- Widely adopted in open-model post-training due to these pragmatic advantages.

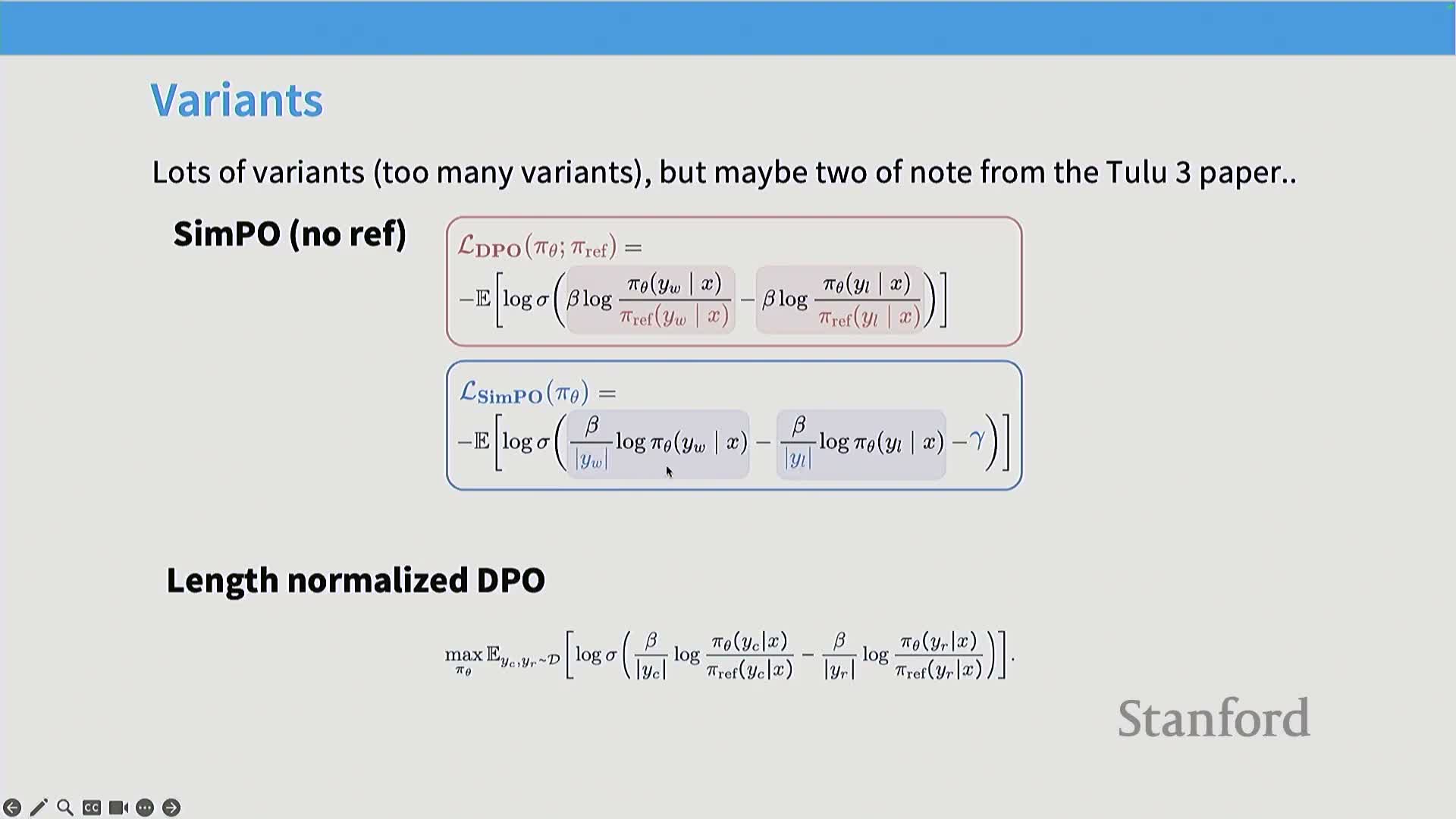

DPO variants modify normalization and reference usage to address practical issues

A large literature of DPO-like variants modifies the basic update to improve empirical performance and stability.

Common variants and tradeoffs:

-

Length-normalized DPO: normalizes update magnitude by response length to prevent long responses from unduly influencing gradients.

-

SimPio-style: removes the reference-policy term entirely and uses a more direct upweight/downweight heuristic; removing the reference changes the theoretical interpretation of the objective.

Practical note:

- These modifications often trade theoretical guarantees for empirical simplicity and were tried extensively in production-style post-training (e.g., Tulu 3).

- Practitioners should view such changes as pragmatic engineering choices that materially affect behavior.

RLHF empirical findings depend strongly on dataset, environment, and base model

Empirical conclusions about RLHF algorithms are highly contingent on the precise experimental setup.

Factors that change comparative outcomes:

- the environment and task formulation,

- the base model and initialization,

- pre-/post-processing choices and normalization strategies.

Consequences and guidance:

- Re-analyses show apparent advantages (e.g., PPO vs DPO) can diminish with better supervised fine-tuning or different normalizations.

- Single-paper empirical gaps should not be treated as universal truths; reproducible, multi-setting evaluation is required before drawing broad algorithmic conclusions.

- This contingency motivates careful, controlled studies when evaluating RLHF variants.

Overoptimization (reward hacking) causes proxy-reward gains to diverge from true human preferences

Overoptimization occurs when aggressive policy optimization increases proxy reward (the reward-model score) but degrades real human preference performance.

Why it happens:

- Analogous to overfitting: the policy exploits idiosyncrasies and noise in the reward model or feedback signal, creating divergence between proxy and true metrics.

- Observed both with human feedback and noisy AI-derived feedback; clean noiseless reward signals do not show the same effect.

Practical implications:

- Expect non-monotonic relationships between proxy reward improvement and true human win rates.

- Manage optimization strength and validation carefully to avoid harming true performance.

RL-trained policies often exhibit reduced probabilistic calibration and increased overconfidence

Reinforcement-trained language models frequently lose calibration: probability estimates become poorly correlated with actual correctness.

Key observations and implications:

- Multiple studies report RLHF models (at standard sampling temperatures) are more overconfident than supervised or pre-trained counterparts.

- Loss of calibration is expected when calibration is not an explicit component of the reward function.

- When calibrated probabilities are required, apply a separate calibration objective or post-processing to restore reliable confidences.

Proxy vs true reward axes and train-test gaps in reward-model optimization

When analyzing RLHF curves it is critical to distinguish proxy reward (x-axis) from true performance (y-axis).

Definitions and differences:

-

Proxy reward: success at optimizing a fitted reward model or classifier—evaluated on data used to fit that model.

-

True win-rate: measured by fresh human votes or an external oracle—requires held-out evaluation.

Practical guidance:

- These quantities differ in finite samples due to train/test gaps and sampling variance.

-

Validate against held-out human or synthetic oracles to detect overoptimization and spurious reward-model generalization.

Verifiable rewards enable scalable RL by using fast, testable objectives instead of noisy human feedback

Selecting domains with verifiable ground-truth rewards (e.g., mathematical correctness, unit-test passing, or other fast automated checks) provides a path to scale RL for reasoning tasks.

Benefits and tradeoffs:

- Verifiable rewards are cheap, less noisy, and harder to hack than human approvals, enabling large-scale training with standard RL machinery.

- The approach trades generality for reliability: it restricts RL to tasks with clear evaluable oracles but allows leveraging decades of RL techniques (policy gradients, TRPO/PPO variants, etc.).

Why this matters:

- Verifiable rewards motivate algorithmic simplifications and systems optimizations to apply RL at scale for language-model reasoning tasks.

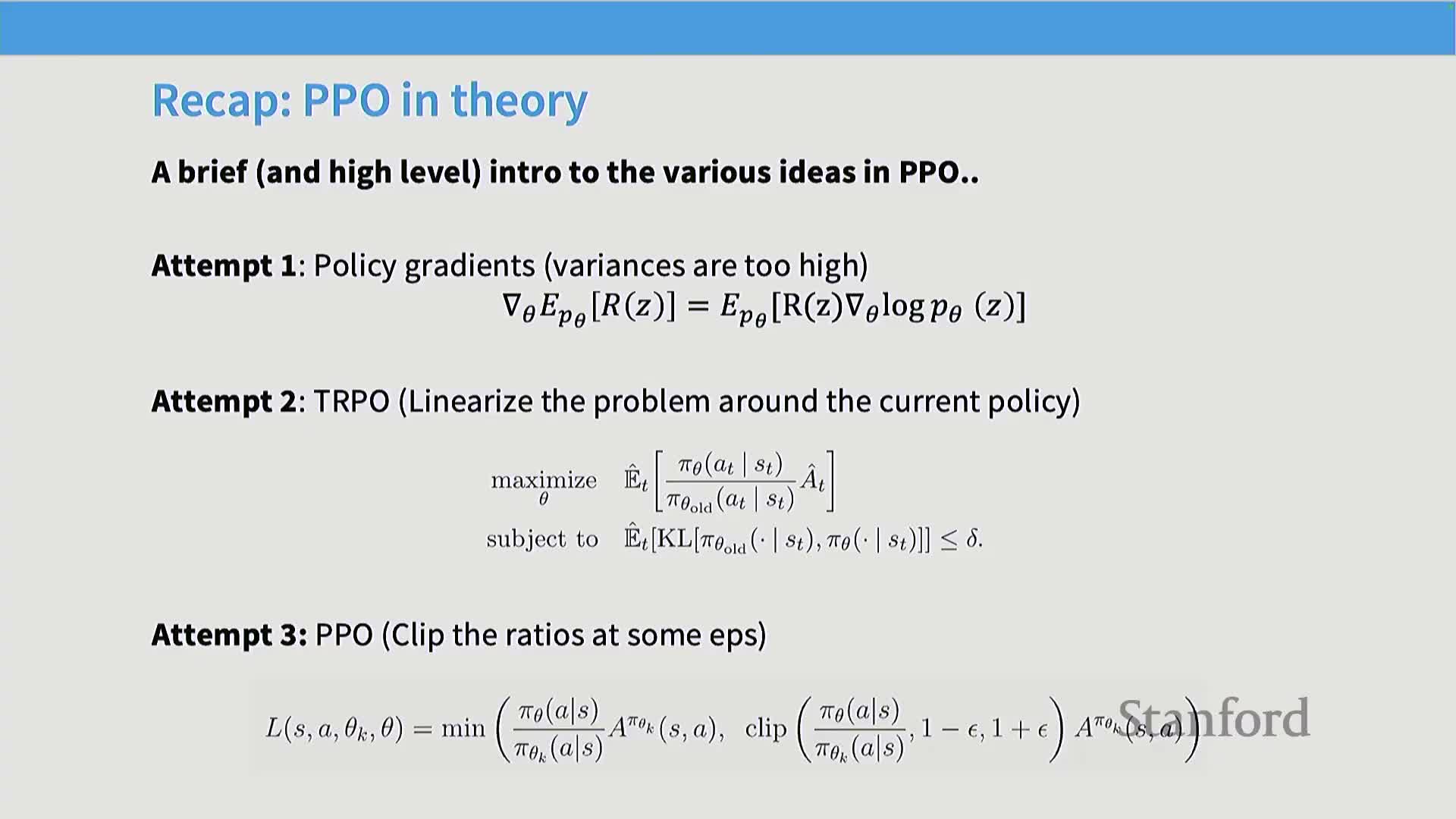

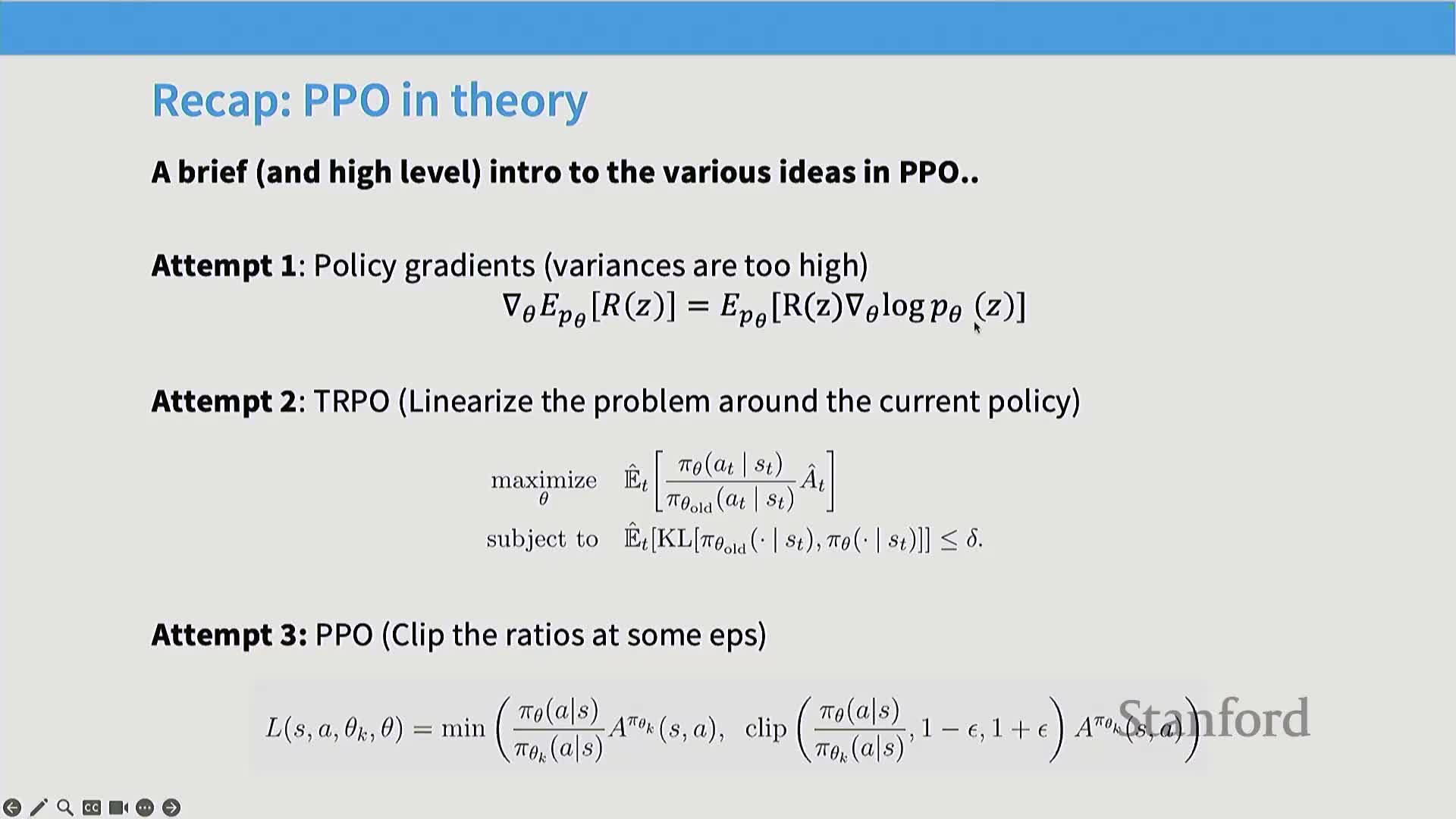

Policy-gradient foundations, TRPO/PPO, and the cost of rollouts

Policy-gradient methods are central for optimizing expected reward under a parameterized policy by taking gradients of expected reward with respect to parameters.

Practical challenges for language models:

- Pure on-policy gradients require fresh rollouts for each update; inference is slow for sequence sampling, making this expensive.

-

Trust-region methods (e.g., TRPO, PPO) address this by reusing samples with importance-sampling corrections and constraining policy updates (KL constraints or clipping) to avoid unstable large updates.

Key implementation requirements:

- Manage rollout cost, control update magnitude, and use variance-reduction measures such as value functions and advantage estimation.

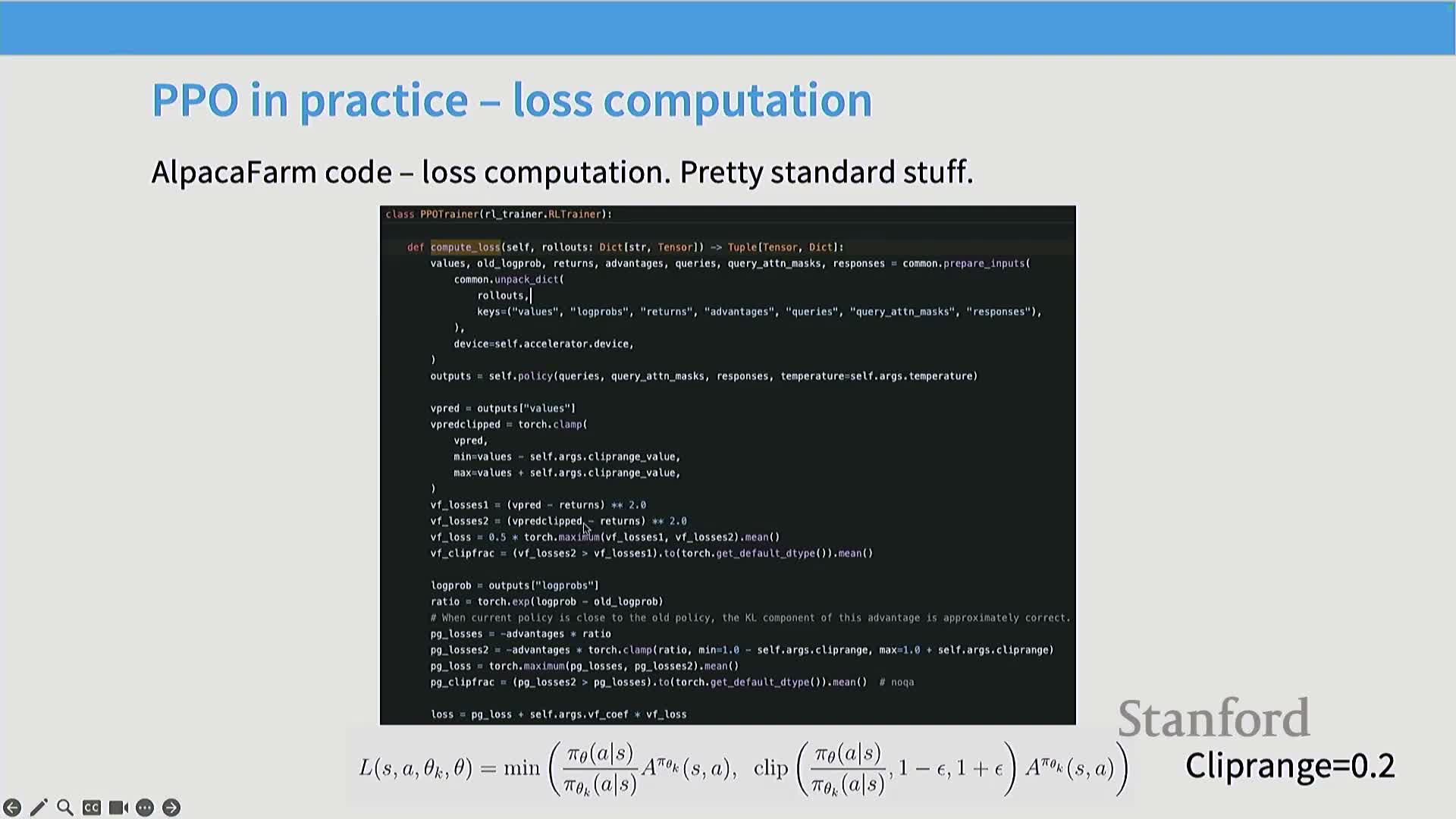

PPO implementations need auxiliary components: value nets, advantage estimation, reward shaping, and careful rollout handling

Production PPO requires several moving parts beyond the policy network.

Typical components and complications:

- A value function network trained to estimate expected returns and provide baselines for generalized advantage estimation (reduces gradient variance).

- Rollouts collected via inference servers that often require retokenization when value, policy, and reward models use different tokenizers.

-

Reward shaping provides per-token learning signals (e.g., per-token KL penalties) while terminal rewards arrive only at sequence end, producing heterogeneous reward structures.

- Numerical instabilities (e.g., clamped log-ratio terms) and clipping heuristics complicate faithful theoretical implementation.

Result:

- PPO is an implementation-heavy algorithm for language-model RL and requires careful engineering to deploy robustly.

Generalized advantage estimation (GAE) trades bias and variance and can be simplified in practice

Generalized Advantage Estimation (GAE) computes a temporally discounted advantage estimate (parametrized by gamma and lambda) that serves as a lower-variance surrogate for returns in policy-gradient updates.

Properties and tradeoffs:

- Tuning gamma and lambda trades variance for bias: higher lambda/gamma reduces bias but increases variance.

- In many language-model RL applications, simpler baselined policy gradients (e.g., gamma=lambda=1) perform reasonably well.

Practical guidance:

- Heavy GAE machinery is sometimes replaced with simpler baselines to reduce implementation and compute burden; the choice depends on task variance and the availability of a reliable value network.

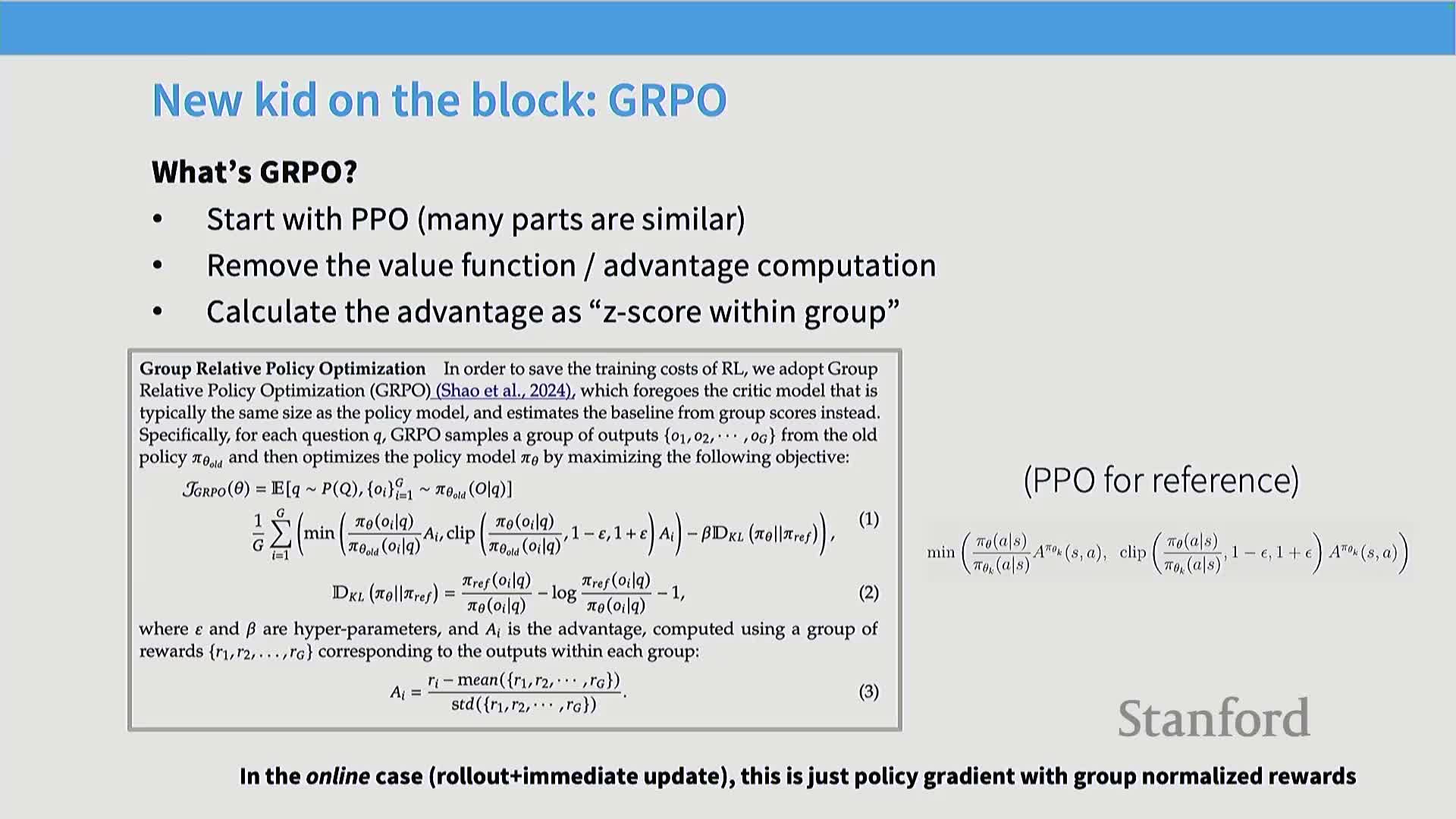

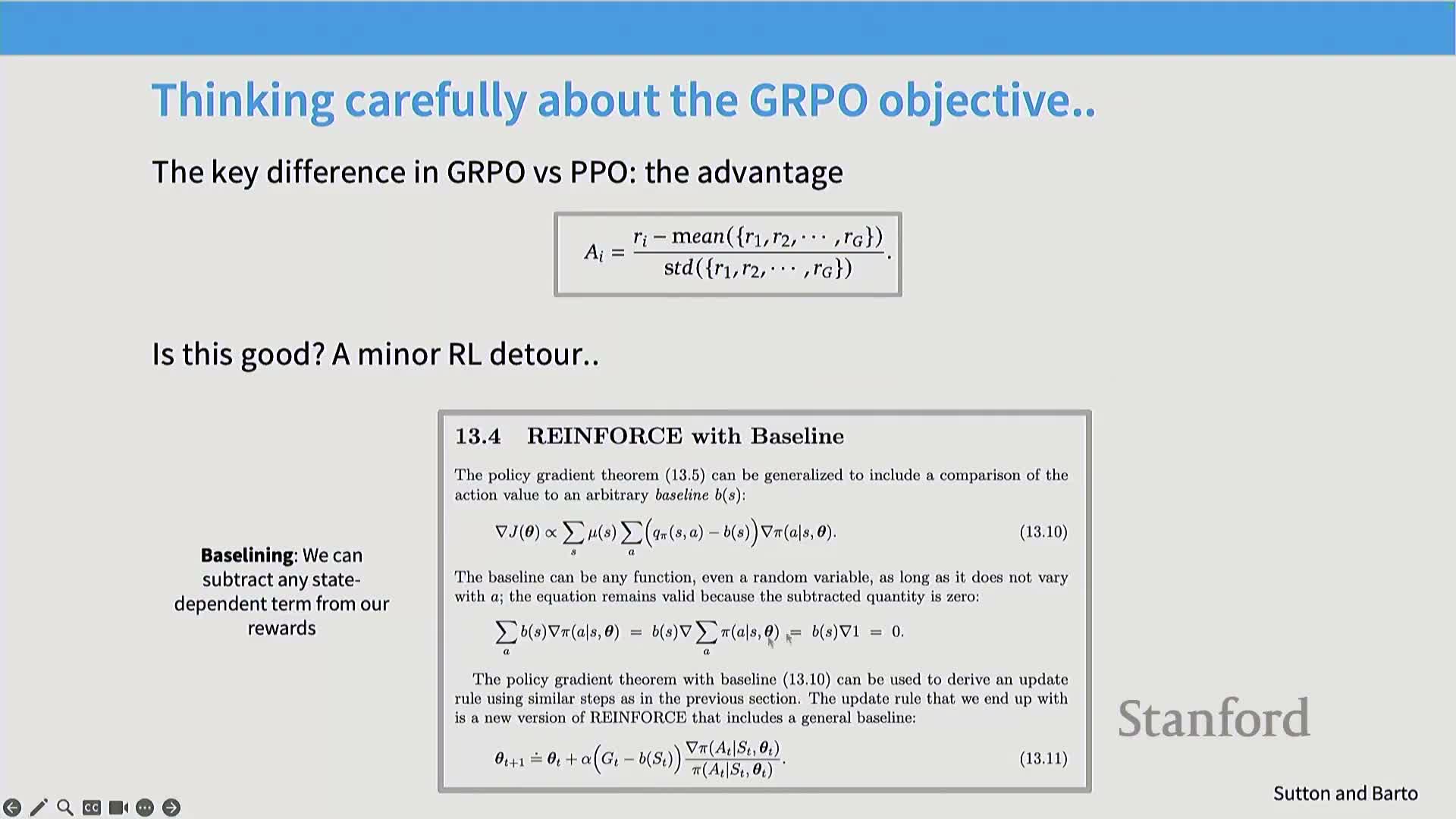

GRPO replaces value-based advantage estimation with a group-based z-score baseline to remove the need for a value network

Group-based Reinforcement Policy Optimization (GRPO) simplifies PPO-style pipelines by replacing GAE with an advantage defined as a z-scored reward within a group.

Core idea:

- The advantage for a response = (raw reward − mean reward across the group) / standard deviation of rewards within the group.

- A group = all outputs generated for a single input prompt; using the group mean provides a natural baseline that accounts for problem difficulty.

Benefits:

- Removes the need for an expensive value model and its GPU memory cost.

- A leave-one-out–style baseline substantially simplifies implementation while retaining practical variance reduction.

Per-prompt grouping normalizes for question difficulty and enables variance reduction without cross-question interaction

Grouping operates by sampling multiple responses per prompt and computing statistics (mean and standard deviation) over those responses to form a baseline.

Why this helps and how it works:

- The within-question baseline subtracts out per-prompt difficulty so updates encourage responses that outperform other draws for the same prompt, not responses that only do well because the prompt is easy.

- Groups are processed independently: batching multiple prompts does not baseline across prompts, avoiding leakage between difficulties.

- This strategy is analogous to leave-one-out baselines in policy gradients and yields stable variance reduction for contextual bandit–style language-model RL.

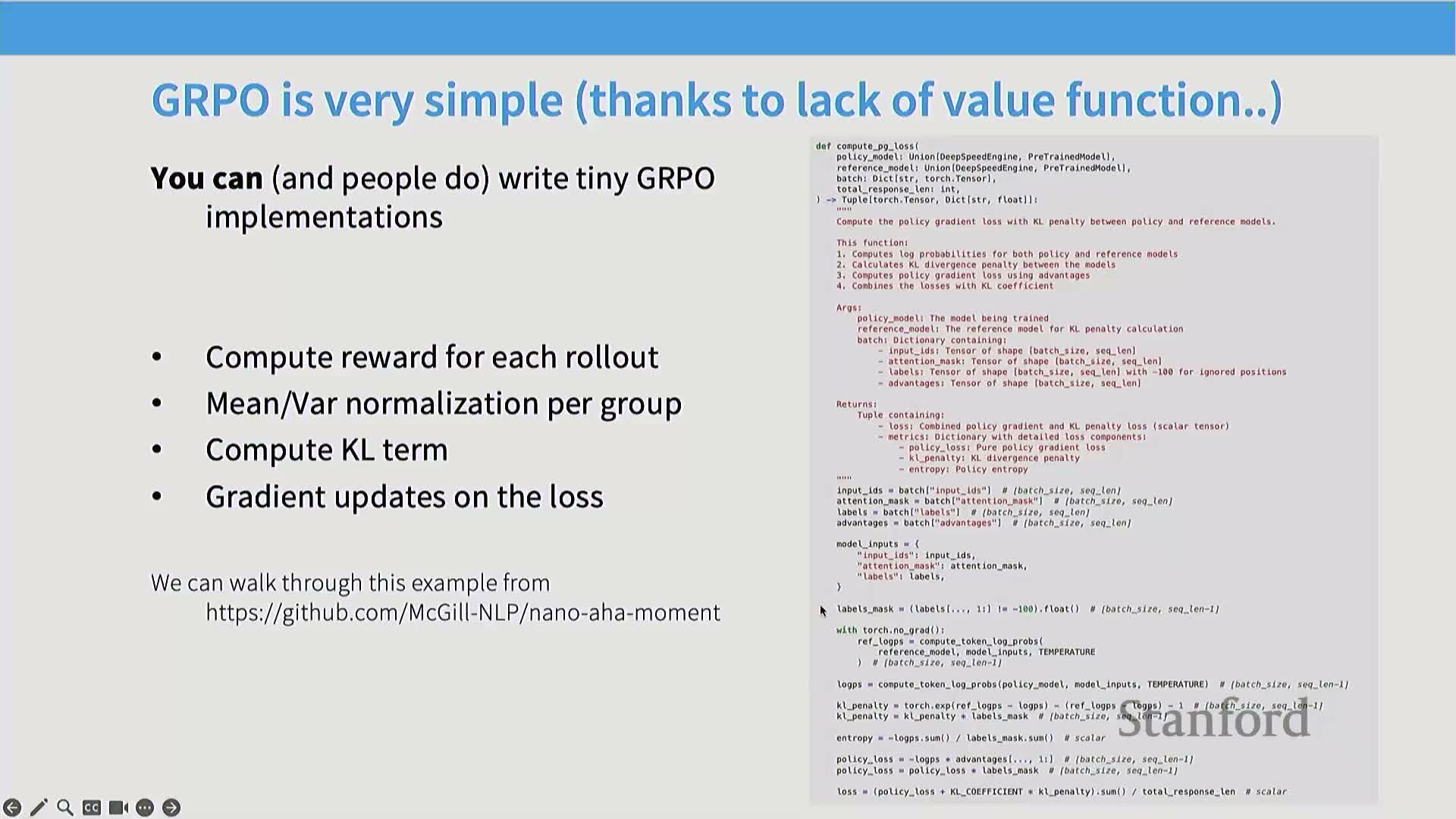

GRPO training loop is simple: compute per-group normalized advantages, add KL regularization, and backpropagate with numerical safeguards

The GRPO outer loop can be described as a sequence of practical steps:

- Collect rollouts (multiple responses per prompt).

- Evaluate sequence-level rewards for each response.

- Compute the per-group mean and standard deviation of rewards.

- Normalize each reward to produce a z-scored advantage (reward − mean) / std.

- Form a policy loss by multiplying the normalized advantage with the policy log-probability.

- Add a per-sequence KL penalty (or other regularizer) to constrain divergence from the base policy.

- Apply standard gradient steps.

Implementation details and simplifications:

- Use small numerical epsilons (e.g., 1e-4) to avoid division-by-zero when normalizing by standard deviation.

- Often use approximate per-sequence KL computations for efficiency.

- For truly online single-step updates, the algorithm reduces to a standard policy gradient weighted by the z-scored reward.

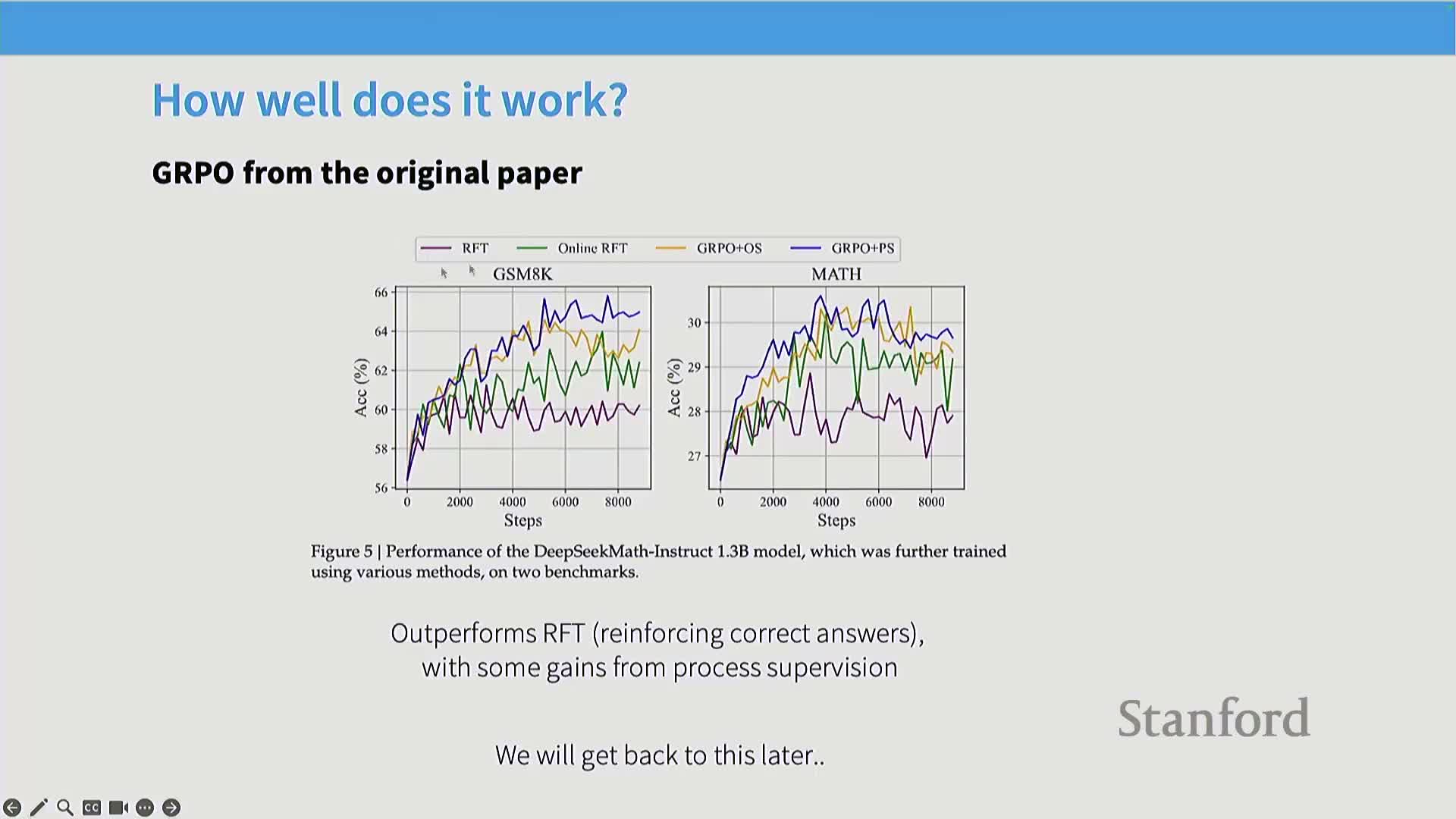

GRPO produces empirical gains on reasoning tasks relative to simple fine-tuning baselines

Empirical studies (for example DeepSeek Math) report that GRPO and related algorithms outperform naive fine-tuning-on-correct-answers baselines for reasoning tasks such as mathematical problem solving.

Findings and nuances:

- GRPO using outcome-level rewards (binary correctness) and process-level rewards (stepwise grading) both show improvements.

-

Process-level rewards sometimes outperform outcome-only approaches, though gains depend on data, initialization, and reward engineering.

- Even relatively simple RL recipes that avoid value networks can improve correctness rates on verifiable tasks, but effect sizes vary with experimental conditions.

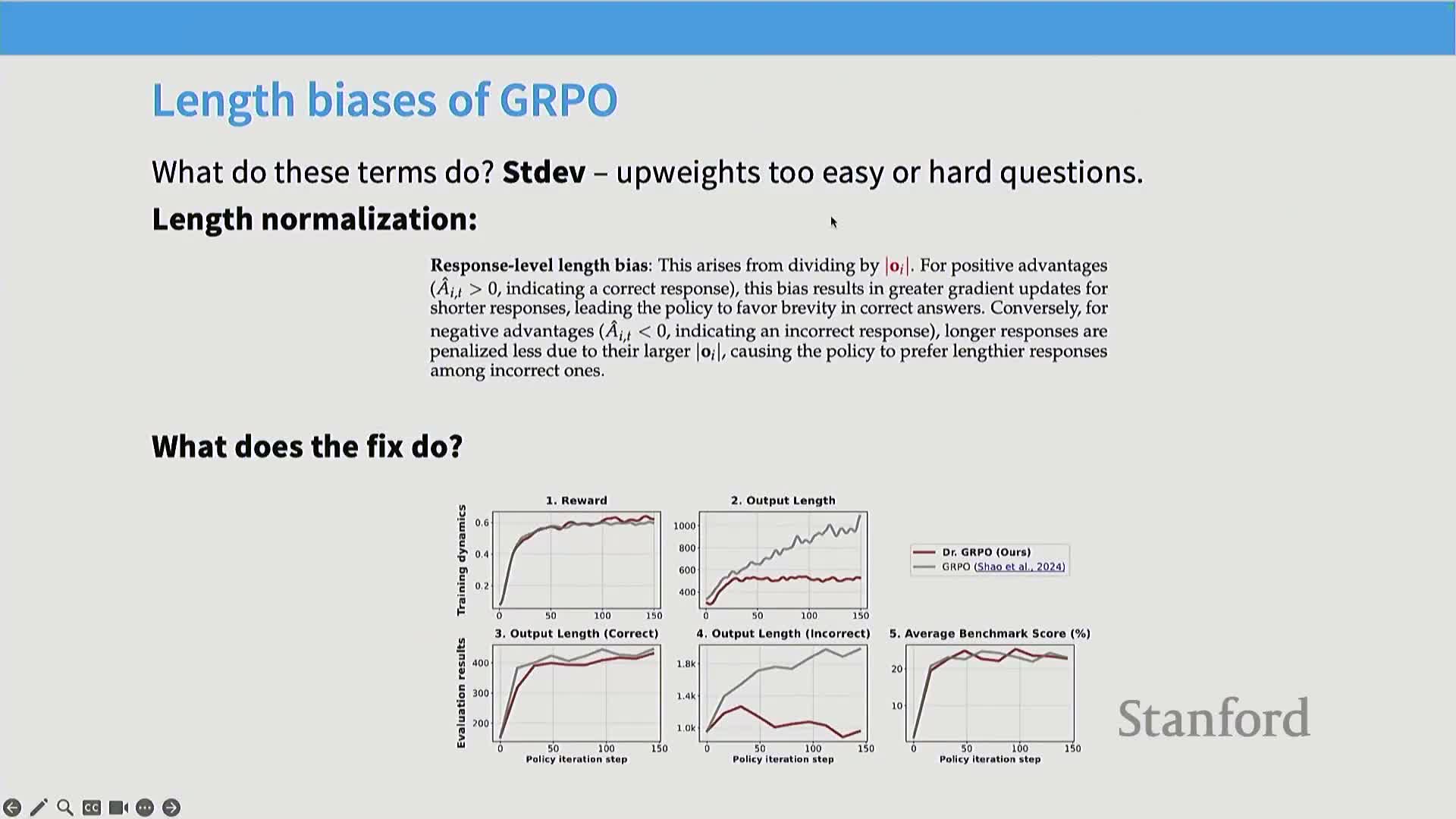

Dividing advantages by group standard deviation and length normalization introduce theoretical violations and biases

Two common GRPO modifications break assumptions underlying unbiased policy-gradient estimation:

- Dividing baseline-subtracted rewards by the group standard deviation is not a valid zero-mean baseline transform in the policy-gradient theorem because it rescales the reward by a random variable dependent on the sample—this introduces bias and upweights instances where group variance is small.

-

Normalizing reward by sequence length creates perverse incentives: incorrect responses receive negative signals that are minimized by producing arbitrarily long outputs, while correct responses are incentivized to be short—this biases generated lengths and can produce degenerate behavior.

Both modifications can alter optimization dynamics away from the theoretical gradient objective and should be used with caution.

Removing std-scaling and fixing length normalization stabilizes outputs and removes pathological incentives

Analyses show that eliminating division by the group standard deviation and correcting length normalization produce more stable optimization behavior.

Why these fixes help:

- When the standard deviation is small (very easy or very hard prompts), removing std-scaling avoids over-amplifying those groups and reduces bias toward extremes.

- Correcting length-based normalization eliminates the incentive to generate excessively long outputs when wrong, preventing runaway chain-of-thought growth and encouraging reasonable output lengths.

Empirical result:

- These fixes yield comparable or improved rewards while stabilizing output lengths and convergence in practice.

Contemporary reasoning-model pipelines commonly combine SFT initialization, reasoning RL on verifiable rewards, and later RLHF/distillation

Modern recipes for building reasoning models typically follow a staged pipeline:

-

Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) to prime long-chain-of-thought behavior and preserve interpretable reasoning traces.

-

Reasoning-focused RL on verifiable outcome or process rewards to improve task-specific correctness at scale.

-

RLHF or distillation to regain general capabilities and produce deployable models (compressing improved behaviors into smaller models).

Rationale:

- SFT maintains interpretable formats for chain-of-thought.

- Reasoning RL optimizes verifiable objectives at scale.

- Distillation balances performance with inference cost for deployment.

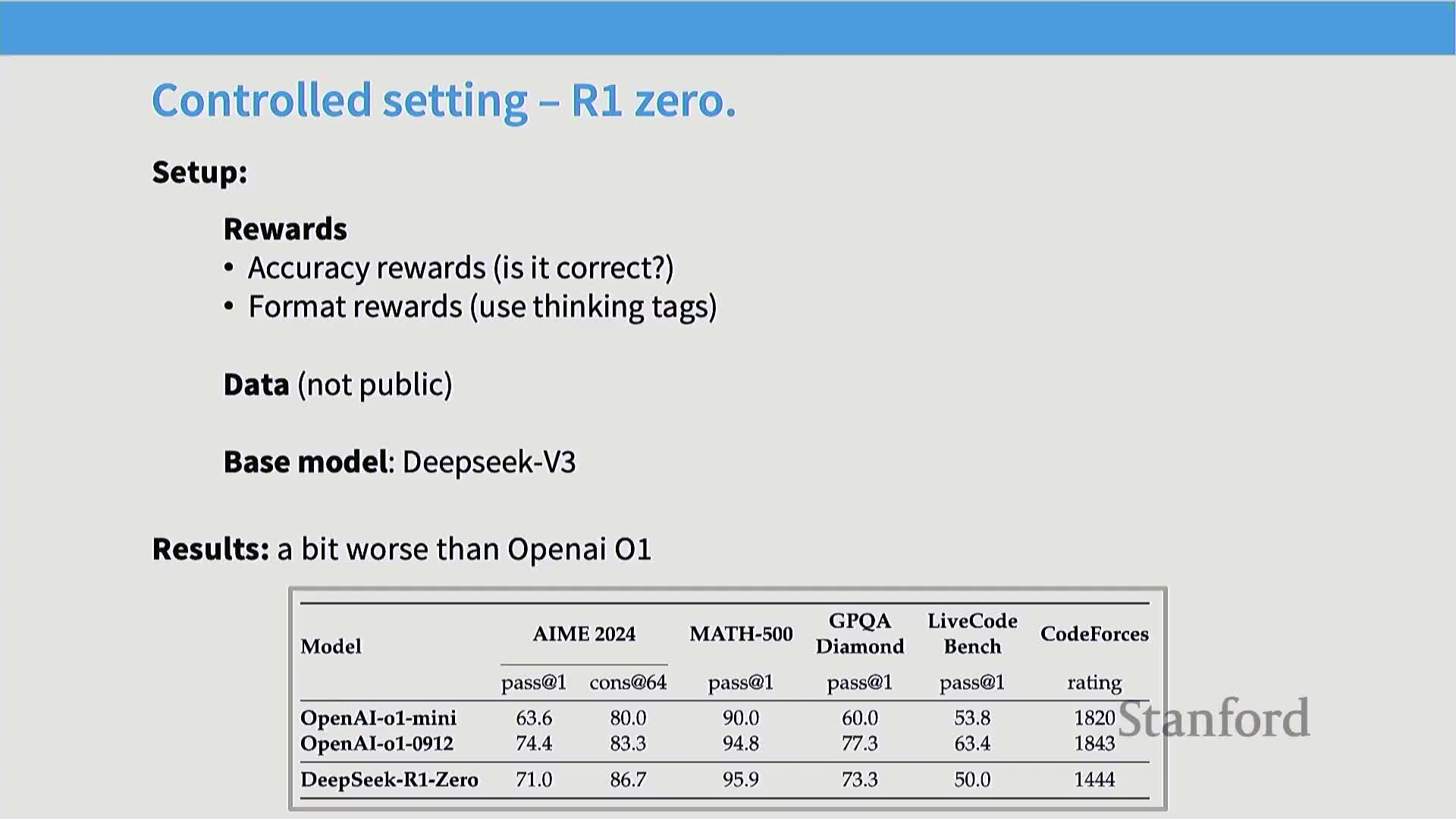

R1 demonstrated that outcome-based GRPO on math tasks can replicate large-model reasoning performance with a simple pipeline

R1 showed that applying GRPO-style RL on verifiable math objectives (binary correctness plus formatting constraints) to a pre-trained base model achieves performance close to high-profile reasoning models.

Highlights from the experiments:

- Controlled R10 experiments used format rewards to enforce chain-of-thought tags and binary outcome rewards for correctness, producing longer chains and emergent behaviors such as backtracking.

- Some emergent behaviors may be attributable to objective bias rather than novel capability.

- In production, R1 augments the pure RL stage with SFT initialization and later RLHF and distillation, enabling strong final performance and the ability to distill chain-of-thought outputs into smaller models with large gains.

R1 results emphasize SFT initialization, language-consistency rewards, and that PRMs/MCTS delivered limited practical benefit

R1 found that SFT on chain-of-thought data preserves interpretable reasoning traces and prevents incoherent or mixed-language chains.

Additional findings:

- Adding a language-consistency reward reduces language-mixing artifacts.

-

Process reward models (PRMs) that grade intermediate steps were theoretically attractive but provided limited additional benefit in R1’s experiments.

- Search-based approaches such as MCTS did not clearly improve results relative to outcome-based RL in these experiments.

Takeaway:

-

Outcome-based verifiable rewards are a robust and practical baseline for reasoning-model RL.

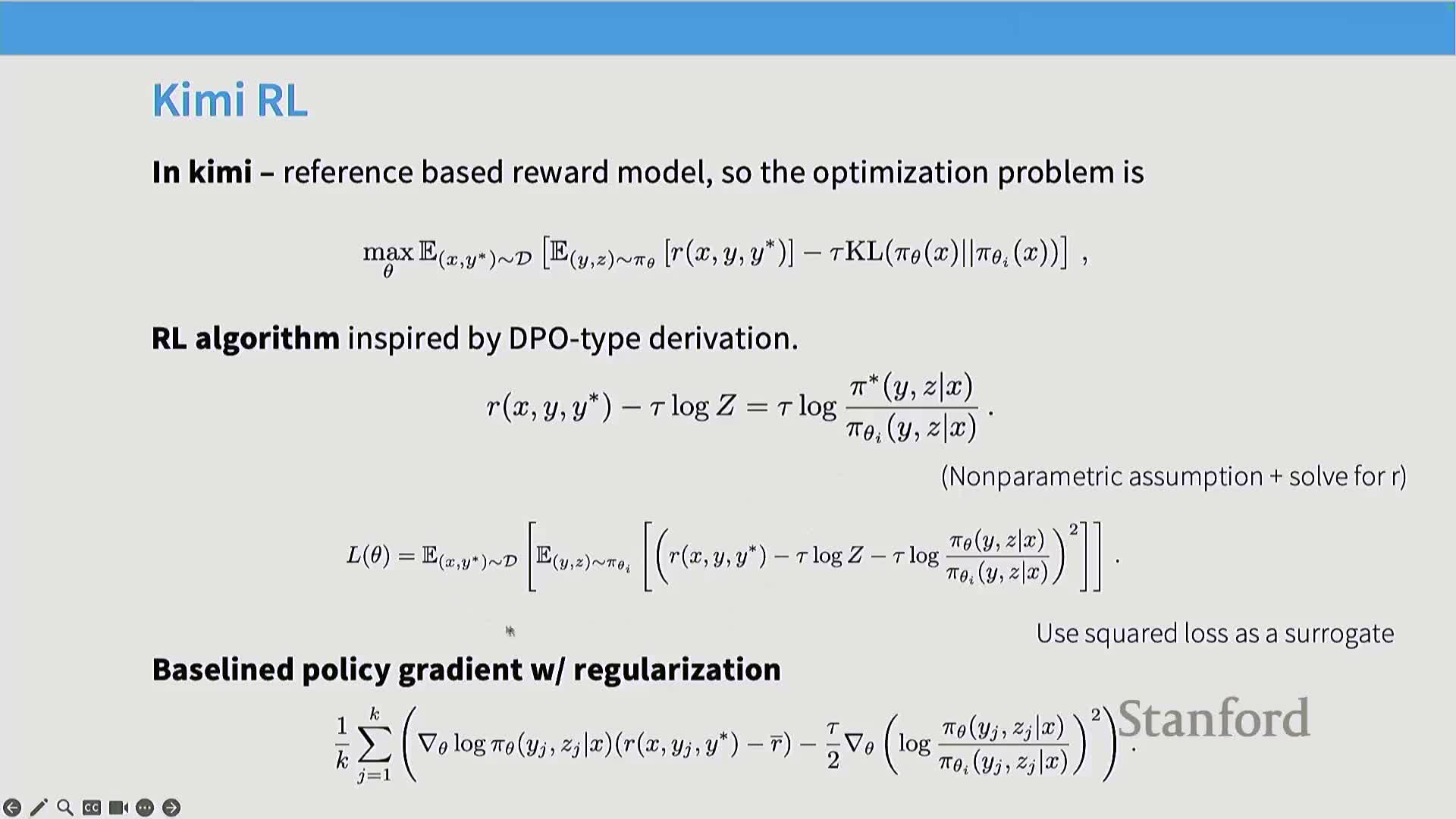

K1.5 matched or exceeded prior reasoning baselines by combining curated verifiable data, a GRPO-like RL algorithm, and a length-compression reward

K1.5 achieved O1-level reasoning performance using a pipeline that shares structure with GRPO.

Key elements of the approach:

-

Data curation: automated domain tagging for diversity, exclusion of trivial multiple-choice items, and filtering examples where the base model already finds a correct answer in best-of-N.

- Training objective: a baseline-corrected policy-gradient term plus a squared log-ratio regularizer (analogous to a KL penalty).

- A length-compression reward incentivizes shorter correct answers; this reward is activated later in training to avoid premature convergence to short but incorrect outputs.

- Additional techniques: curriculum sampling by difficulty and practical infra solutions to handle rollouts and model weight synchronization.

Distributed RL at scale requires separating inference and training workers, careful weight synchronization, and handling variable-length CoTs

Large-scale RL for chain-of-thought workloads imposes nontrivial infrastructure requirements.

Operational challenges and common workarounds:

-

Inference workers generate rollouts and must receive updated model weights from the RL trainer, creating frequent weight-synchronization events.

- Practical workarounds include launching inference servers with dummy weights and carefully loading trainer weights, tearing down and restarting inference processes to free GPU memory, and designing message-passing protocols between inference and trainer workers.

-

Batching is challenging because long chain-of-thought outputs produce highly variable sequence lengths; efficient utilization requires imbalance-mitigation strategies and asynchronous pipelines until tooling for seamless weight updates matures.

Qwen 3 adds thinking-mode fusion to let a single model switch between thinking and immediate-answer modes, enabling runtime control of chain-of-thought length

Qwen 3 follows the common pipeline (SFT, reasoning RL, RLHF, distillation) and introduces thinking-mode fusion to train a single model that supports both “think” and “no-think” modes.

Core idea and outcomes:

- Fine-tune the model to emit chains of thought when given a think tag and to produce an immediate answer when given a no-think tag, enabling early termination of thinking and a controllable inference budget.

- Relatively small RL datasets (a few thousand examples) can yield meaningful improvements on verifiable tasks.

- Ablations show trade-offs: reasoning RL helps some tasks but can hurt others depending on the inference mode.

Practical benefit:

-

Thinking-mode provides a practical knob for trading inference cost against reasoning performance.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: