CS336 Lecture 17 - Alignment - RL - Part 2

- Course orientation and lecture goals

- Reinforcement learning formulation for language models: states, actions, rewards, and dynamics

- Policy and objective in outcome-reward LM reinforcement learning

- Policy gradient derivation: gradient of expected reward via log-derivative trick

- Naive policy gradient as reward-weighted supervised fine-tuning and implications of binary rewards

- Dataset non-stationarity and contrast with continuous reward RLHF

- Baselines for variance reduction in policy gradient

- Toy two-state example illustrating variance pitfalls and baseline benefits

- Optimal baseline expression and practical heuristic choice

- Advantage function and unified delta notation for algorithms

- GRPO lineage and group-structured variance reduction in LM settings

- Toy sorting task and reward design alternatives

- Simplified model architecture and sampling strategy for the sorting task

- Computing deltas: centering, normalization, and optional max-only selection

- Log-probability extraction and naive policy-gradient loss computation

- Freezing reference quantities (no-grad) and importance-ratio pitfalls

- Credit assignment and discounting considerations for outcome rewards

- GRPO clipped objective and KL regularization

- Algorithm components, inner/outer loop structure, and computational workflow

- Why a separate KL reference vs. old policy and initialization considerations

- Empirical sorting-task experiments and learning curve interpretation

- Conclusions: promise of RL for LMs and scaling challenges

mindmap

Policy-gradient RL for LMs outcome rewards

LM formulation

state = prompt + tokens

action = next token / whole response

transition = append

reward = outcome sparse, delayed

Gradient & deltas

score-function estimator

advantage = return − Vs

delta = reward/centered/normalized

Variance reduction

state-dependent baselines

centering & normalization

no-grad cached pi_old

GRPO & grouped updates

multiple responses per prompt

per-prompt baselines group mean

clipping + KL reference

Reward design

binary vs shaped rewards

partial credit position/adjacency

max-only vs smooth shaping

Implementation & workflow

outer rollouts, inner optimization

cache logits, freeze references

tradeoff: inference cost vs samples

Challenges & scaling

sparse rewards & credit assignment

high Monte Carlo variance

engineering: multi-model orchestration

Course orientation and lecture goals

This session is positioned at the end of the quarter and will deep-dive into policy gradient methods for reinforcement learning (RL) applied to language models (LMs).

- Goals:

- Expand on prior coverage of RL with verifiable rewards rather than introduce fundamentally new theory.

- Provide mathematical detail and code-oriented examples that connect theory to practice.

- Focus on algorithm mechanics (e.g., policy gradients, GRPO) and on practical implementation concerns.

- Expand on prior coverage of RL with verifiable rewards rather than introduce fundamentally new theory.

- Framing:

- Treats the lecture as a continuation and an application-focused elaboration of earlier material.

- Treats the lecture as a continuation and an application-focused elaboration of earlier material.

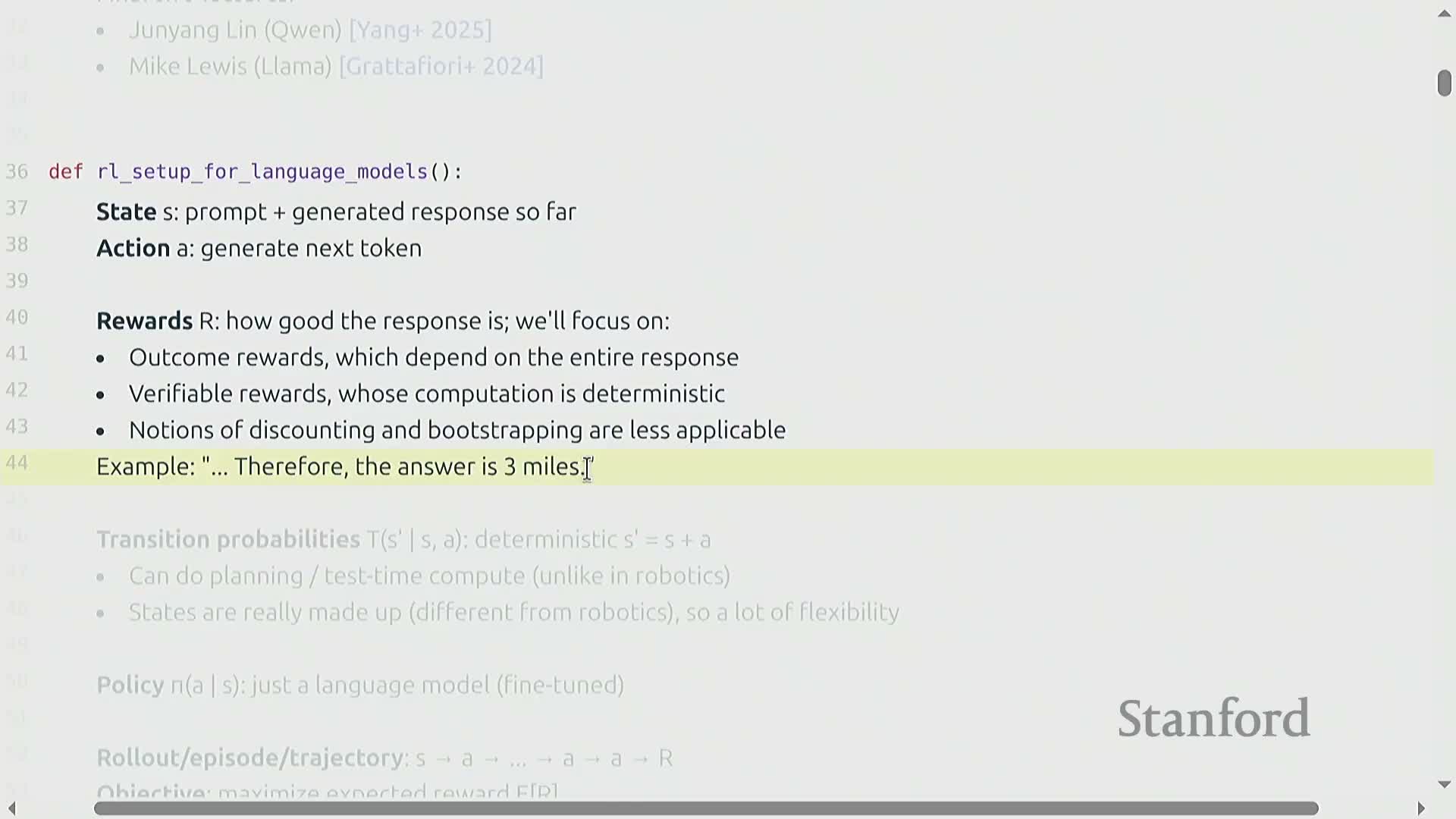

Reinforcement learning formulation for language models: states, actions, rewards, and dynamics

-

State (LM setting): the prompt concatenated with the tokens generated so far.

-

Action: generating the next token.

- Reward characteristics:

-

Outcome-based and deterministic: rewards depend on the entire generated response (verifiable).

- This makes signals sparse and delayed, but conceptually simpler than interactive environments.

-

Outcome-based and deterministic: rewards depend on the entire generated response (verifiable).

- Transition dynamics:

- Trivial string concatenation: state’ = state + action.

- This simplicity enables planning or test-time computation that physical robotics typically cannot use.

- Trivial string concatenation: state’ = state + action.

- State representation challenges:

- The LM synthesizes arbitrary internal tokens, so states are ungrounded text and can include internal scratchpad behavior.

- Main challenge: ensure those token sequences produce verifiable, correct outcomes rather than merely reaching reachable but meaningless states.

- The LM synthesizes arbitrary internal tokens, so states are ungrounded text and can include internal scratchpad behavior.

Policy and objective in outcome-reward LM reinforcement learning

-

Policy: an LM conditioned on the current token sequence (prompt + generated tokens).

-

Training objective: maximize expected reward over the distribution of prompts and the policy’s token outputs.

- Outcome-reward simplification:

- When rewards are outcome-based, treat the entire response as a single action a with a single reward R.

- This yields a simpler expected-reward expression and implementation.

- When rewards are outcome-based, treat the entire response as a single action a with a single reward R.

- Practical setup:

- Policies often initialize from pretrained LMs and are then fine-tuned via policy optimization.

-

Rollouts produce trajectories that yield a scalar reward at episode end.

- The objective integrates over environment-provided prompts and the stochastic policy’s responses to compute the expected return, which is the target for gradient-based optimization.

- Policies often initialize from pretrained LMs and are then fine-tuned via policy optimization.

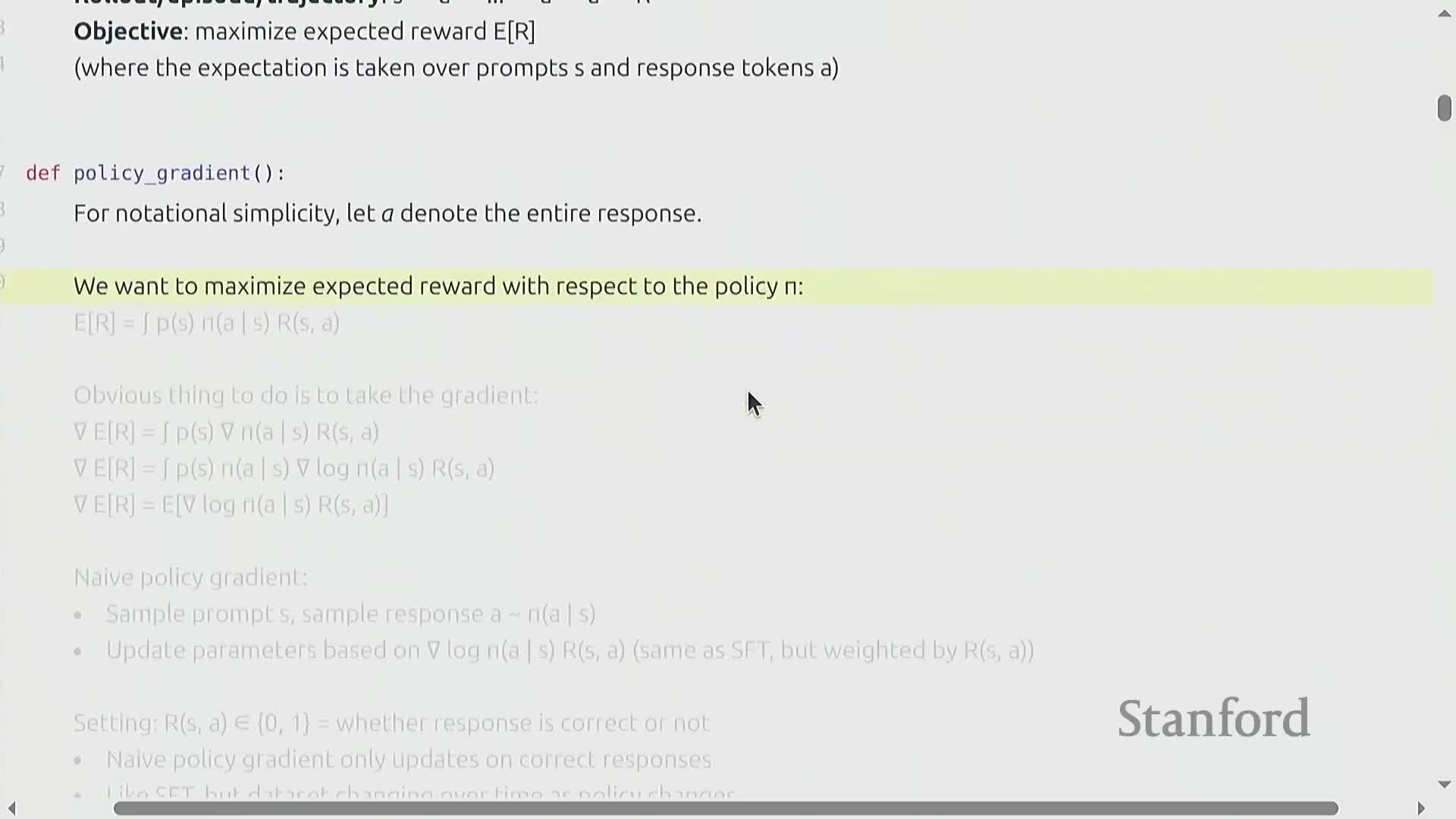

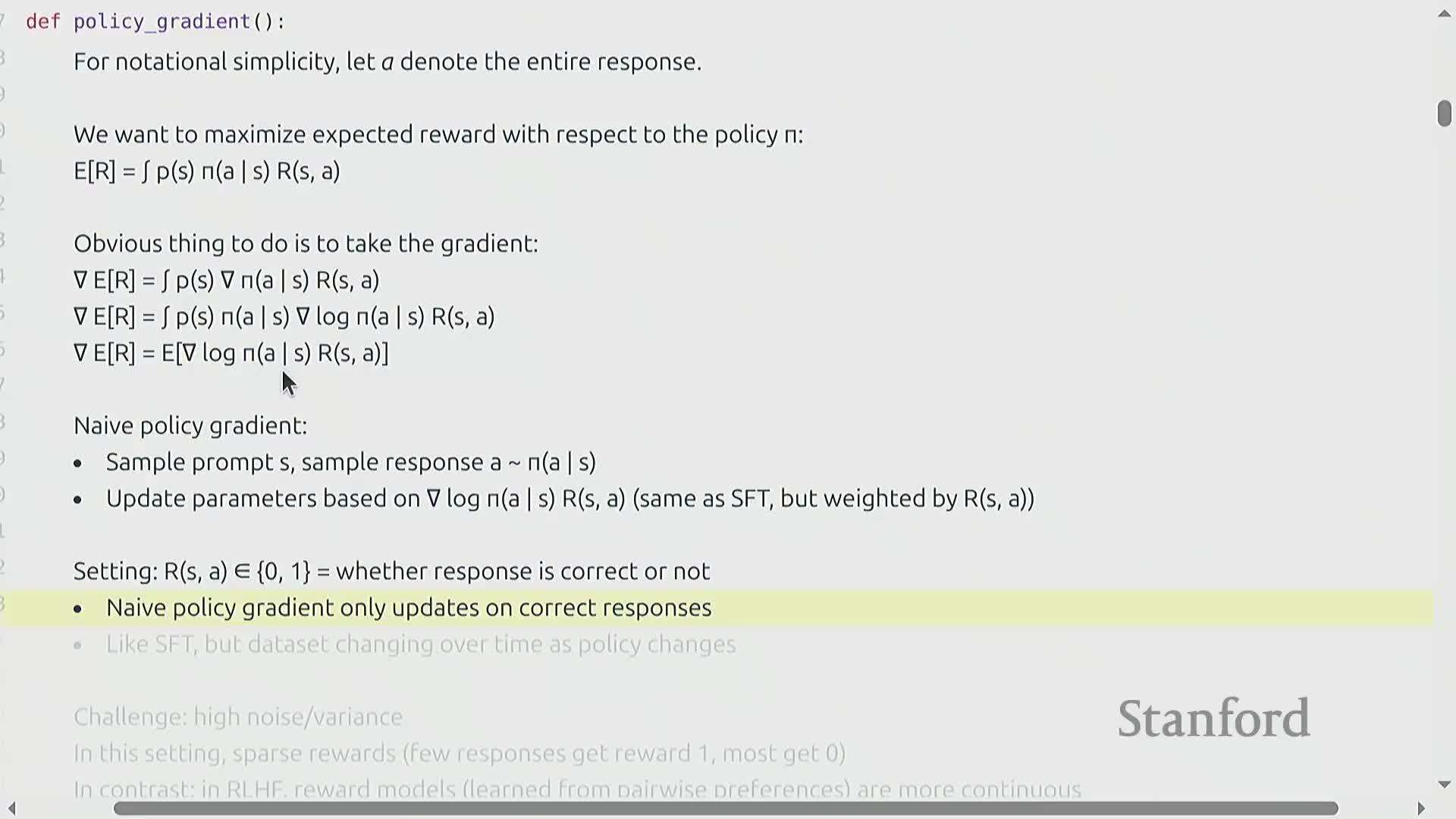

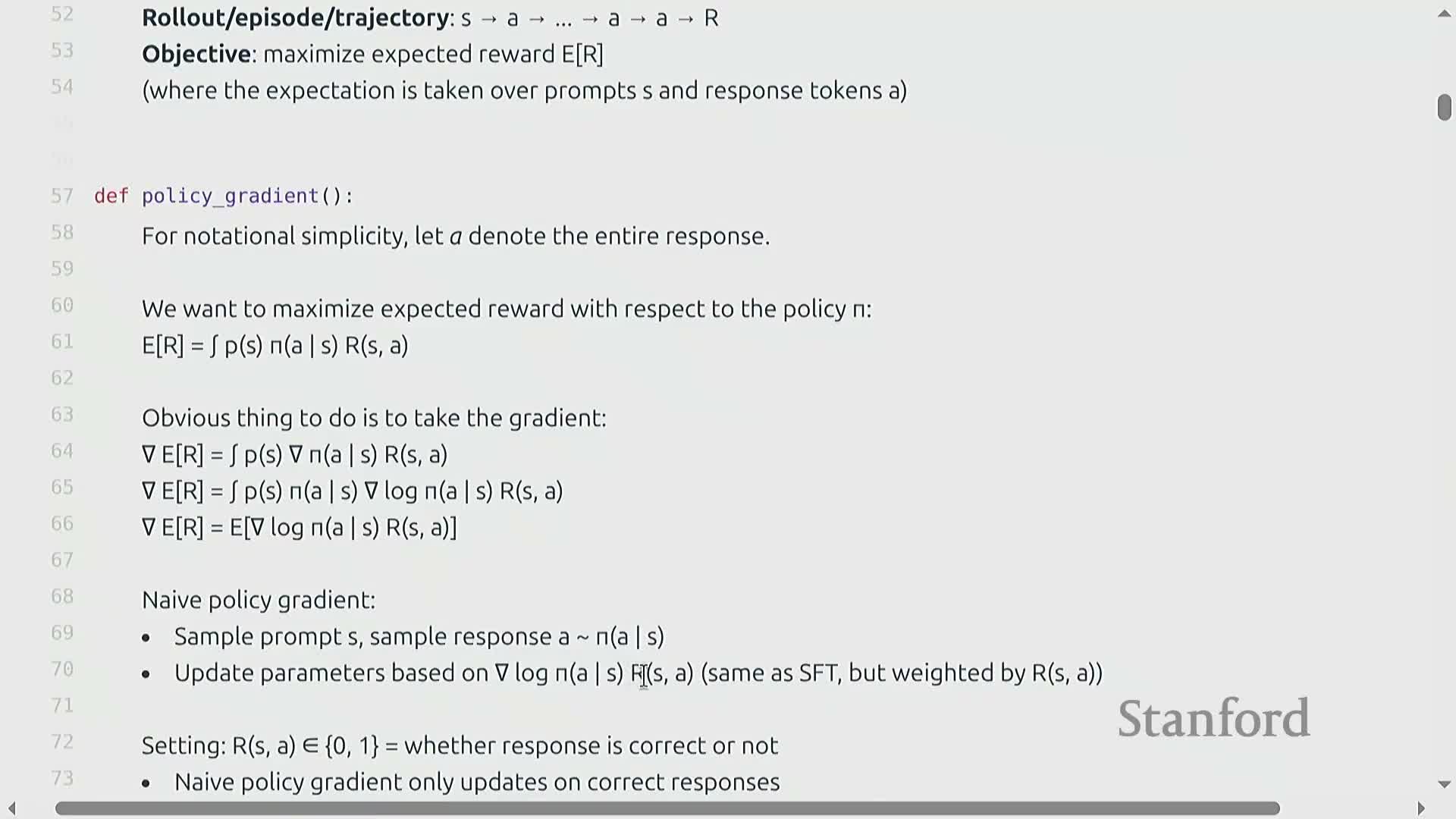

Policy gradient derivation: gradient of expected reward via log-derivative trick

- Derivation sketch:

- Differentiate expected reward w.r.t. policy parameters and apply the log-derivative (score function) identity to move the gradient inside the expectation.

-

Result: an expectation of **∇ log π(a s)** weighted by the return (reward).

- Differentiate expected reward w.r.t. policy parameters and apply the log-derivative (score function) identity to move the gradient inside the expectation.

- Properties:

- This gives an unbiased Monte Carlo estimator when sampling prompts and actions.

- In the outcome-reward setting, treating the entire response as a single action further simplifies notation and implementation.

- This score-function estimator is the basis for sampling-based updates that seek to increase expected reward.

- This gives an unbiased Monte Carlo estimator when sampling prompts and actions.

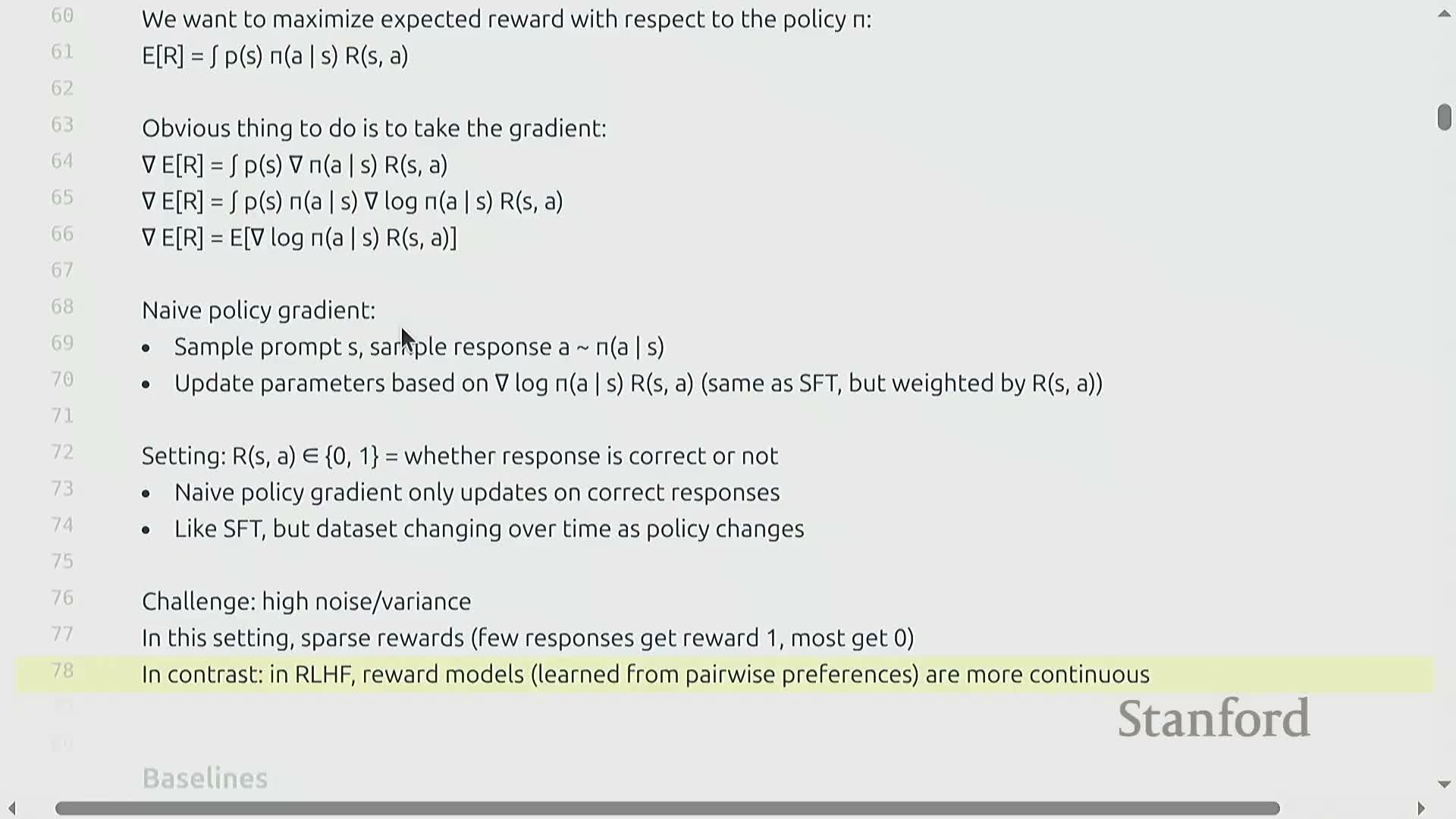

Naive policy gradient as reward-weighted supervised fine-tuning and implications of binary rewards

-

Naive policy gradient update:

- Sample prompts and model responses, then apply gradient steps proportional to the sampled reward.

- Analogy: similar to supervised fine-tuning (SFT), but responses are weighted by reward rather than matched to fixed human targets.

- Sample prompts and model responses, then apply gradient steps proportional to the sampled reward.

- Special cases and failure modes:

- With binary rewards (0/1), updates occur only for rewarded responses: effectively SFT on the subset of model outputs deemed correct.

- In sparse-reward regimes, if the policy rarely produces positive responses, gradients are near zero and learning can stall.

- Conclusion: naive sampling without variance reduction or reward shaping can leave the model stuck when initial performance is poor.

- With binary rewards (0/1), updates occur only for rewarded responses: effectively SFT on the subset of model outputs deemed correct.

Dataset non-stationarity and contrast with continuous reward RLHF

- Non-stationarity:

- Policy optimization changes the policy that generates training examples, so the empirical dataset evolves across iterations.

- This can be beneficial if the policy discovers easy positives and generalizes to harder prompts, but it complicates analysis and monitoring because the data distribution shifts.

- Policy optimization changes the policy that generates training examples, so the empirical dataset evolves across iterations.

- Reward-model contrast:

-

RL with human feedback typically uses a learned, continuous reward model, which provides graded values and reduces sparsity relative to binary verifiable rewards.

- The choice between verifiable outcome rewards and learned reward models affects algorithm design, hyperparameter choices, and intuitions about training dynamics.

-

RL with human feedback typically uses a learned, continuous reward model, which provides graded values and reduces sparsity relative to binary verifiable rewards.

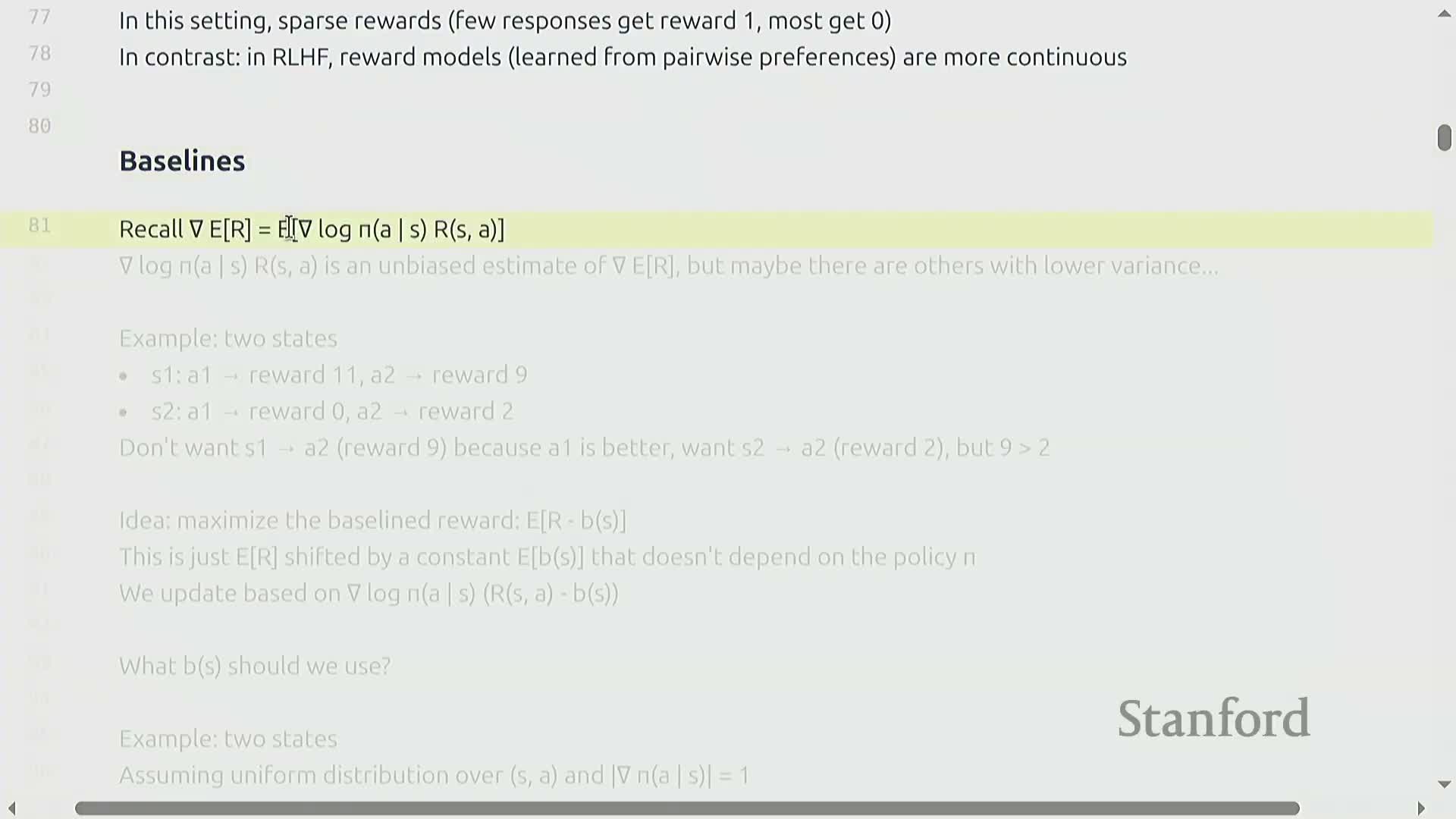

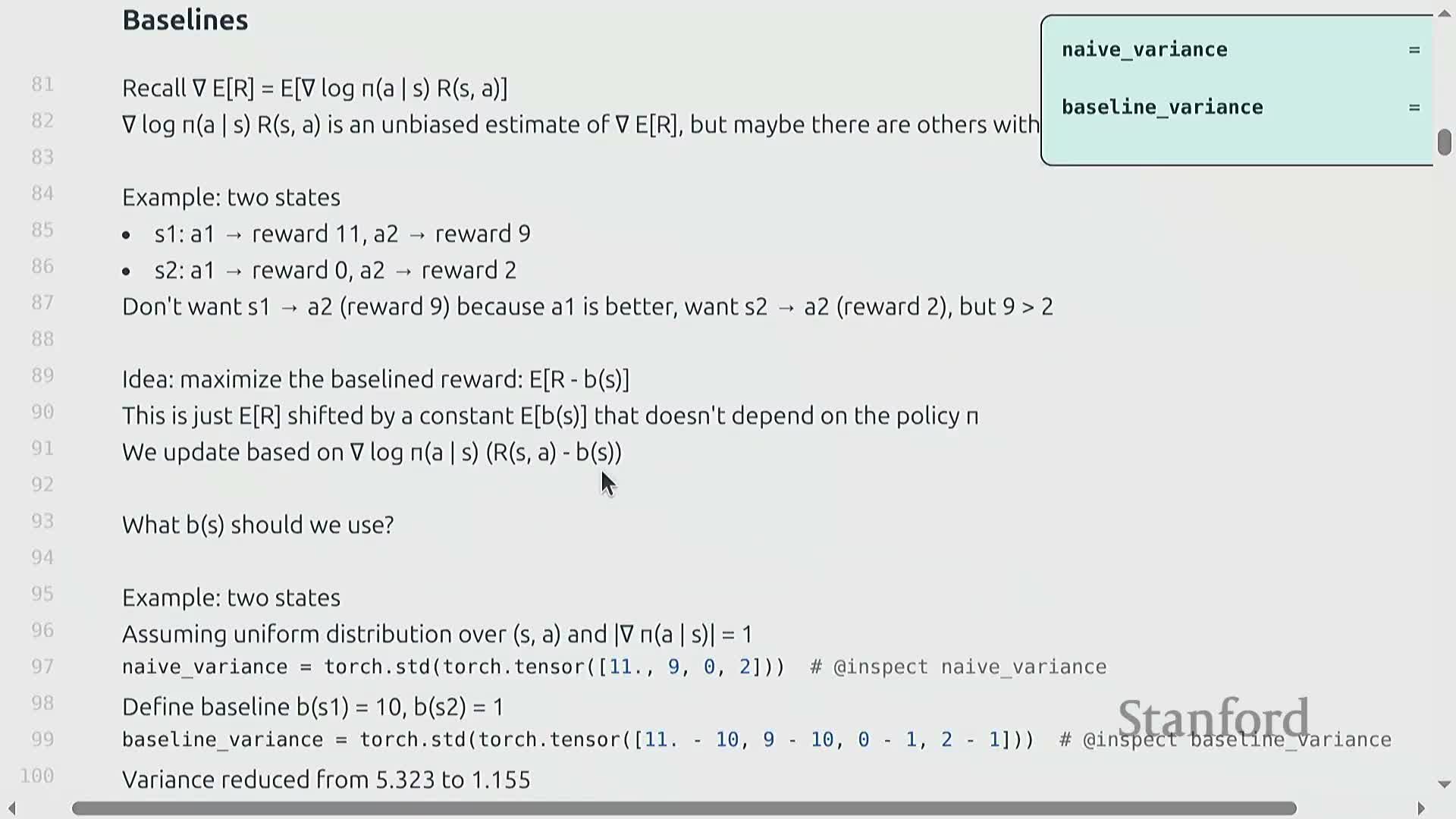

Baselines for variance reduction in policy gradient

-

Baseline b(s):

- Any function of state (but not of action) that is subtracted from returns in the policy gradient estimator to reduce variance without biasing the gradient.

- Any function of state (but not of action) that is subtracted from returns in the policy gradient estimator to reduce variance without biasing the gradient.

- Why it’s unbiased:

- Subtracting b(s) leaves the expected gradient unchanged because the baseline term factors out of the expectation over actions for a given state and contributes zero in expectation.

- Subtracting b(s) leaves the expected gradient unchanged because the baseline term factors out of the expectation over actions for a given state and contributes zero in expectation.

- Practical notes:

- Baselines are fundamental to stabilize and accelerate convergence by centering the reward signal.

- Valid baselines include fixed constants or learned value estimators, provided they do not depend on the action.

- The design of b(s) substantially affects gradient variance and empirical learning speed.

- Baselines are fundamental to stabilize and accelerate convergence by centering the reward signal.

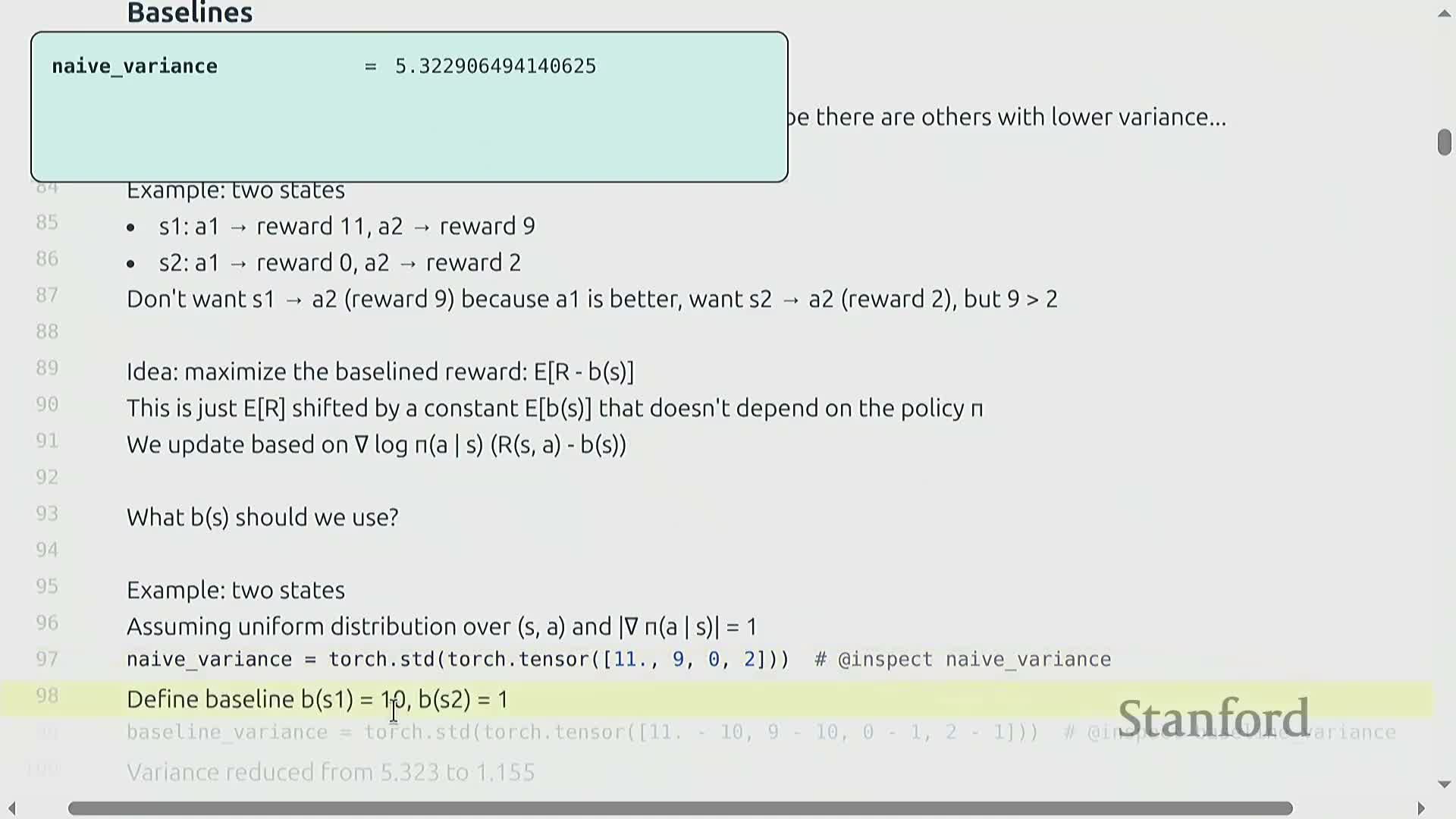

Toy two-state example illustrating variance pitfalls and baseline benefits

- Two-state toy example (intended insight):

- Two prompts (states) with different per-action rewards show how naive updates can favor misleadingly high absolute rewards in certain states and produce suboptimal policies.

- If the policy randomly selects an action that yields high reward in an easy state, repeated updates can amplify that action and eliminate the true global optimum—an instance of high-variance, myopic updates.

- Two prompts (states) with different per-action rewards show how naive updates can favor misleadingly high absolute rewards in certain states and produce suboptimal policies.

- Remedy:

- Introduce a state-dependent baseline (e.g., subtract per-state expected reward) to center rewards, dramatically reducing variance and preventing harmful relative gradients.

- The example quantifies how appropriate baselines can shrink variance by multiple factors and improve convergence behavior.

- Introduce a state-dependent baseline (e.g., subtract per-state expected reward) to center rewards, dramatically reducing variance and preventing harmful relative gradients.

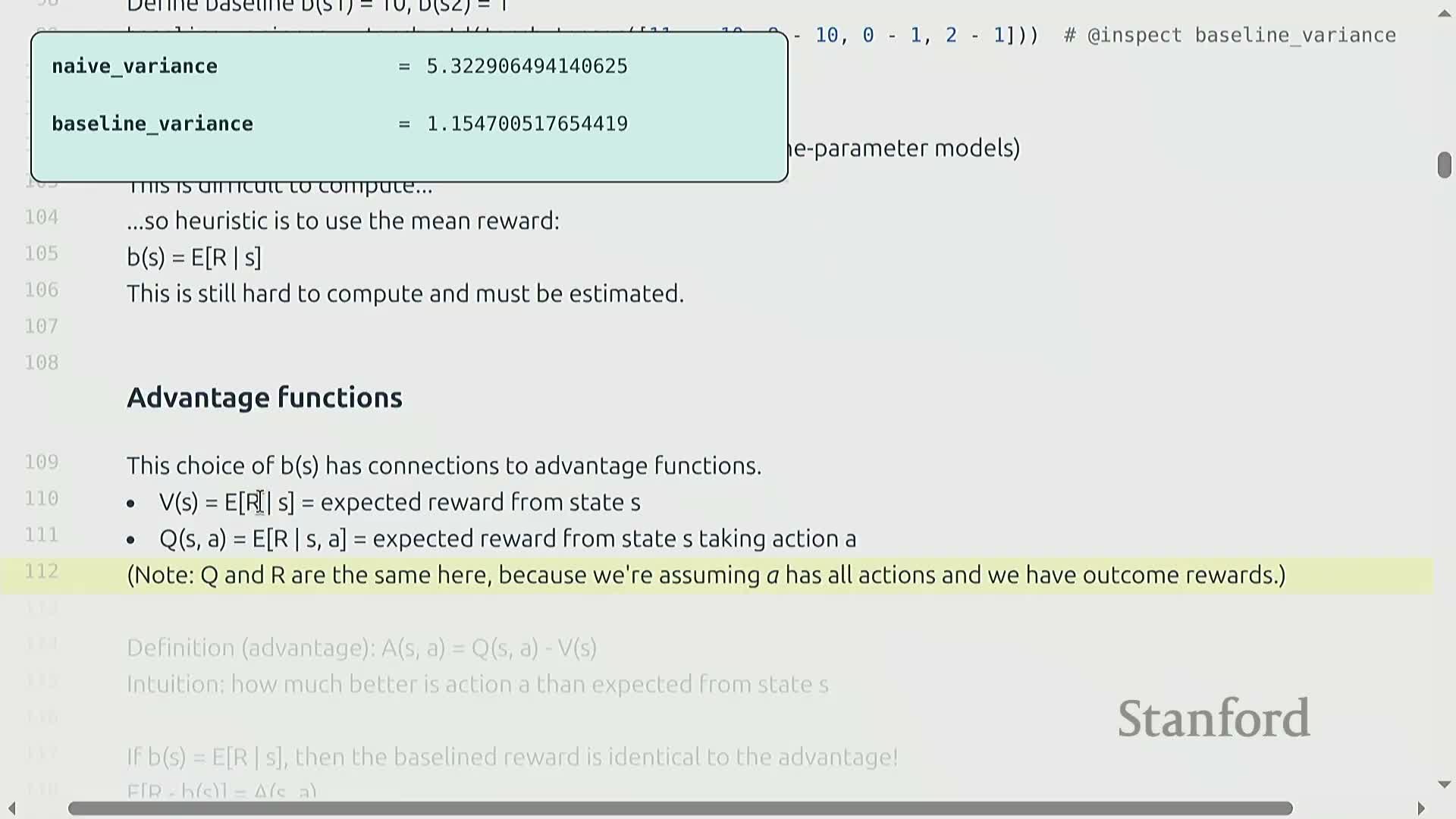

Optimal baseline expression and practical heuristic choice

- Optimal baseline properties:

- For scalar-parameter models, the variance-optimal baseline has a closed-form involving expectations of squared score-function terms weighted by returns.

- In higher dimensions, the optimal solution requires covariance matrices and becomes impractical to compute exactly.

- For scalar-parameter models, the variance-optimal baseline has a closed-form involving expectations of squared score-function terms weighted by returns.

- Practical heuristic:

- Use the estimated expected reward given state (value estimate) as the baseline—this approximates the advantage function and typically yields substantial variance reduction.

- Value estimates are tractable to obtain via sampling or simple learned value functions, so implementations favor these computable approximations balancing cost and variance reduction.

- Use the estimated expected reward given state (value estimate) as the baseline—this approximates the advantage function and typically yields substantial variance reduction.

Advantage function and unified delta notation for algorithms

-

Advantage function A(s,a):

- Defined as Q(s,a) − V(s): how much better action a is relative to average behavior at state s.

- Provides a principled baseline choice when available.

- Defined as Q(s,a) − V(s): how much better action a is relative to average behavior at state s.

- Outcome-reward simplification:

- In the outcome-reward LM setting, Q and the return R coincide when treating the entire response as the return, so A = return − expected return given state.

- In the outcome-reward LM setting, Q and the return R coincide when treating the entire response as the return, so A = return − expected return given state.

- Implementation abstraction:

- Many algorithms adopt a unified scalar delta to represent whatever multiplier (reward, centered reward, normalized advantage, etc.) is used with the log-probability gradient.

- Variants differ primarily in how delta is computed, clarifying that modern policy-gradient techniques scale the score-function gradient by a carefully chosen delta to control variance and bias.

- Many algorithms adopt a unified scalar delta to represent whatever multiplier (reward, centered reward, normalized advantage, etc.) is used with the log-probability gradient.

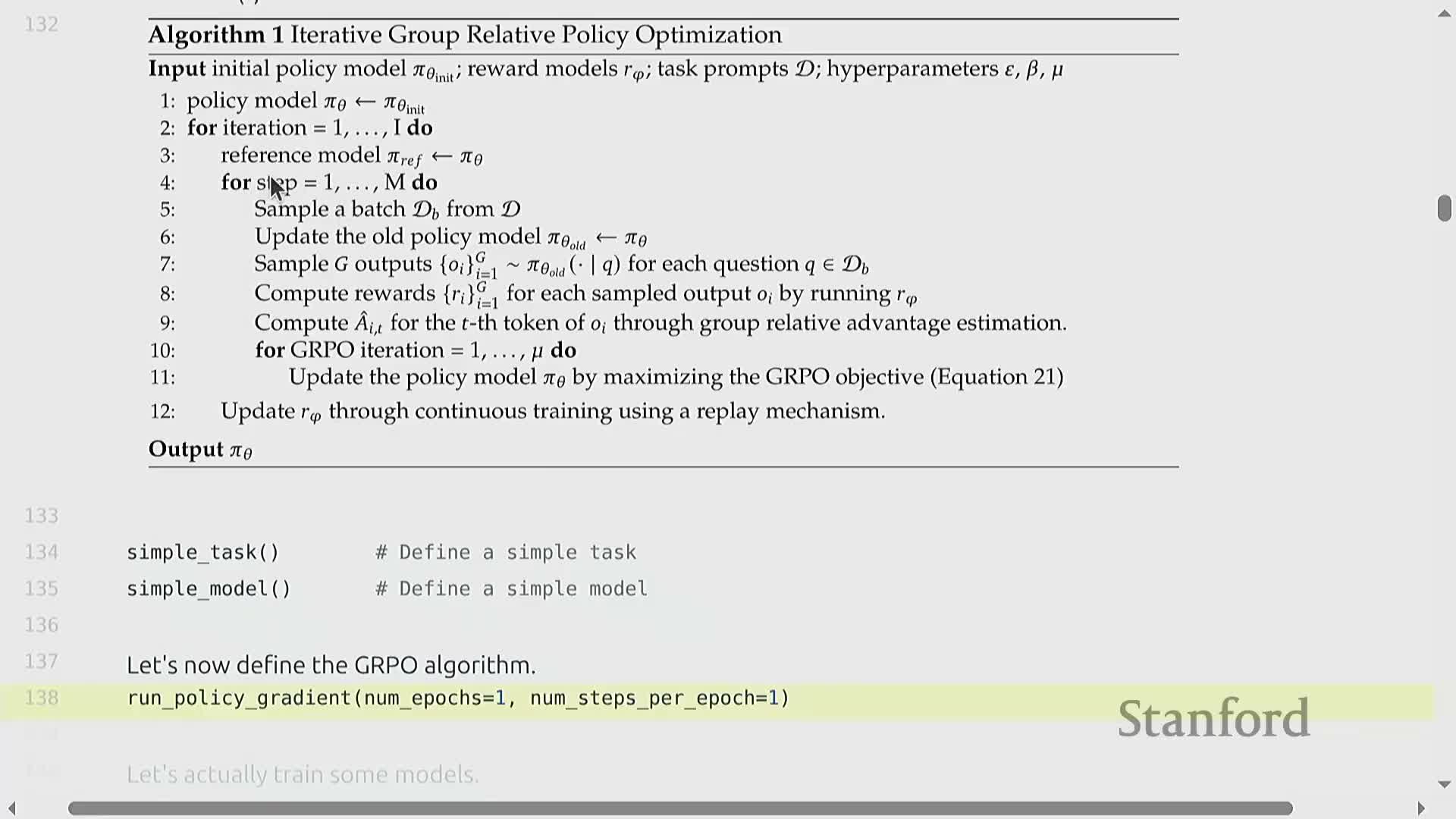

GRPO lineage and group-structured variance reduction in LM settings

- Lineage and structure exploitation:

-

GRPO and related algorithms evolved from the PPO/DPO lineage but exploit structure specific to language modeling.

- Key LM structure: you can sample multiple responses per prompt, forming natural groups for per-prompt baselines (group means).

-

GRPO and related algorithms evolved from the PPO/DPO lineage but exploit structure specific to language modeling.

- Benefits of grouped sampling:

- Compute an empirical baseline across responses from the same prompt, which reduces variance without requiring a global learned value function.

- When rollouts are naturally grouped (many responses per prompt), GRPO-style relative updates are practical and effective.

- In environments without grouping, alternative value-estimation methods are required.

- Compute an empirical baseline across responses from the same prompt, which reduces variance without requiring a global learned value function.

- Algorithmic consequences:

- Group structure motivates clipping and normalization strategies that compare responses relative to their prompt-specific cohort.

- Group structure motivates clipping and normalization strategies that compare responses relative to their prompt-specific cohort.

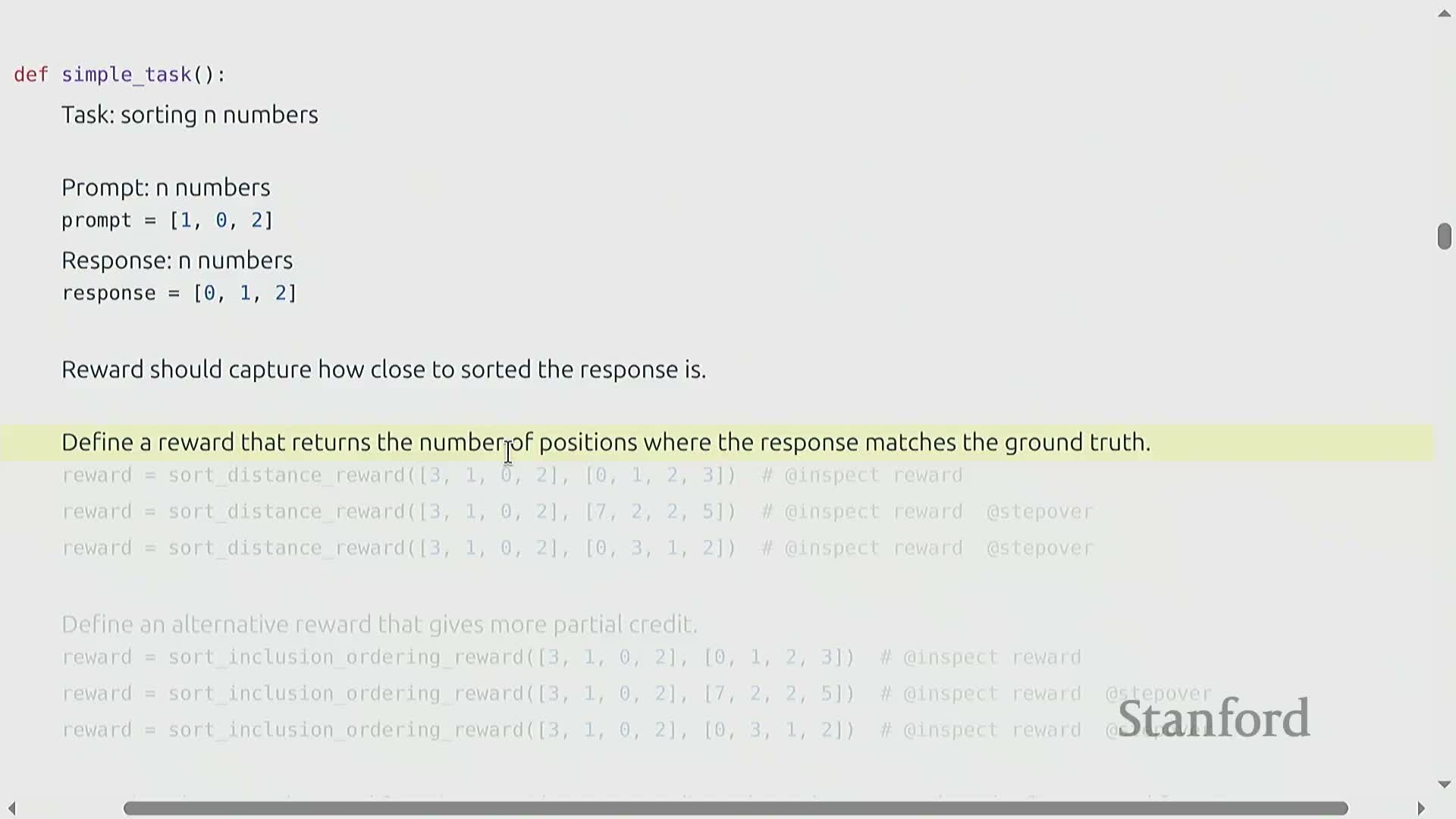

Toy sorting task and reward design alternatives

- Toy environment: sorting n numbers.

- Prompt: a sequence of numbers.

- Desired response: the sorted sequence.

- Reward must quantify closeness to ground truth.

- Prompt: a sequence of numbers.

- Possible reward formulations:

-

Binary correct/incorrect: severe sparsity.

-

Position-match counts: partial credit by summing positions that match the sorted result.

-

Inclusion-plus-adjacency: points for presence of prompt tokens and for correctly sorted adjacent pairs—richer shaping signals.

-

Binary correct/incorrect: severe sparsity.

- Reward-engineering trade-offs:

-

Too sparse: prevents learning.

-

Too permissive: can be exploited or mislead optimization.

- Designing a reward that balances informativeness and robustness is a critical practical decision.

-

Too sparse: prevents learning.

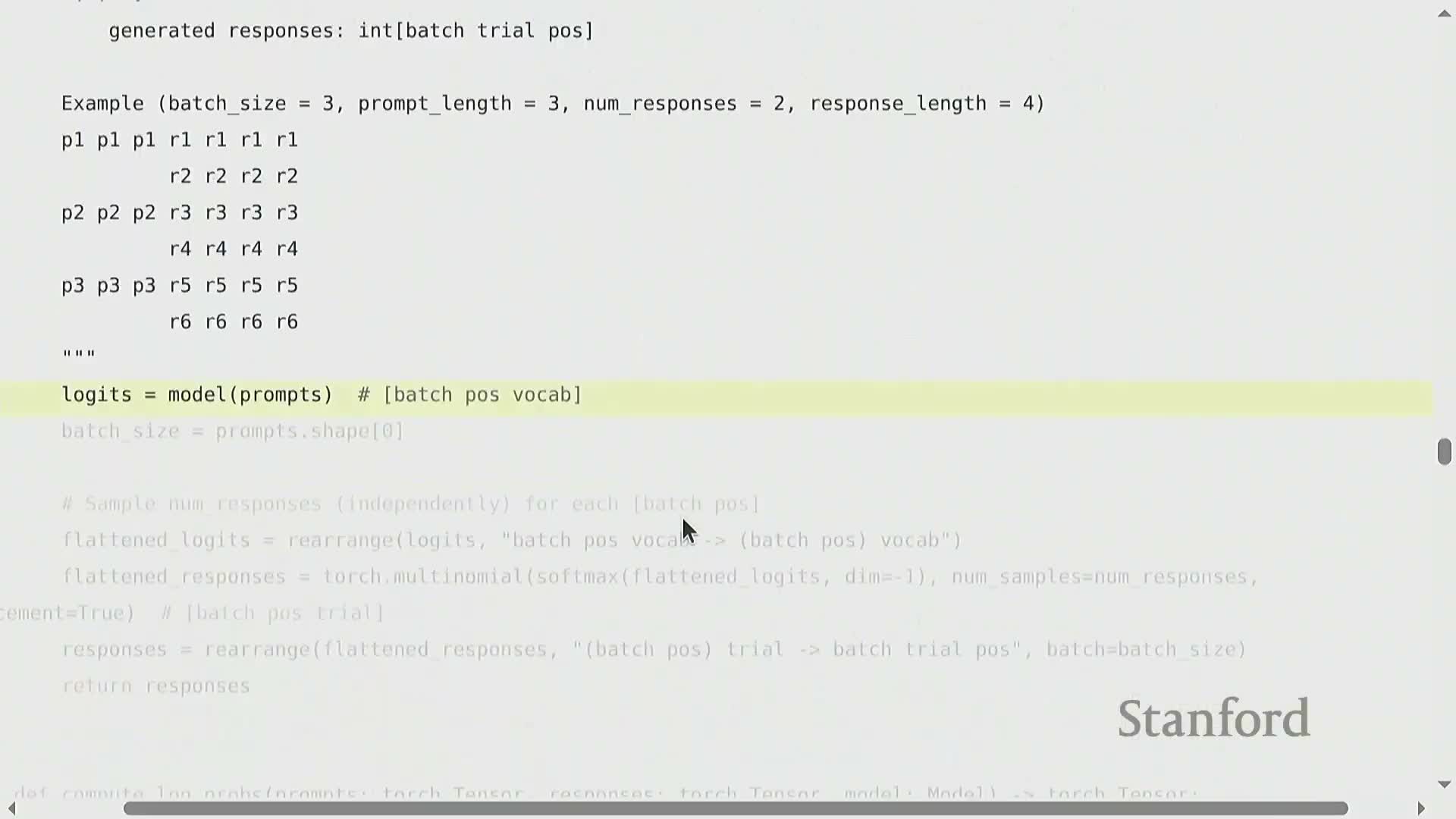

Simplified model architecture and sampling strategy for the sorting task

- Minimal parametric model for on-laptop experiments:

- Fixed, equal prompt and response lengths to simplify indexing.

-

Positional information captured via per-position parameter matrices.

-

Encoding collapses position embeddings into a prompt summary.

-

Decoding produces logits per response position independently (non-autoregressive) to simplify implementation.

- Fixed, equal prompt and response lengths to simplify indexing.

- Forward pass:

- Map batch-by-position inputs through embeddings and per-position linear transforms to produce logits over the vocabulary for each output position.

- Use logits to sample multiple response trials per prompt.

- Map batch-by-position inputs through embeddings and per-position linear transforms to produce logits over the vocabulary for each output position.

- Rationale:

- Trades realism for tractability but preserves core elements needed to illustrate policy-gradient training, grouped sampling, and reward-driven updates.

- Trades realism for tractability but preserves core elements needed to illustrate policy-gradient training, grouped sampling, and reward-driven updates.

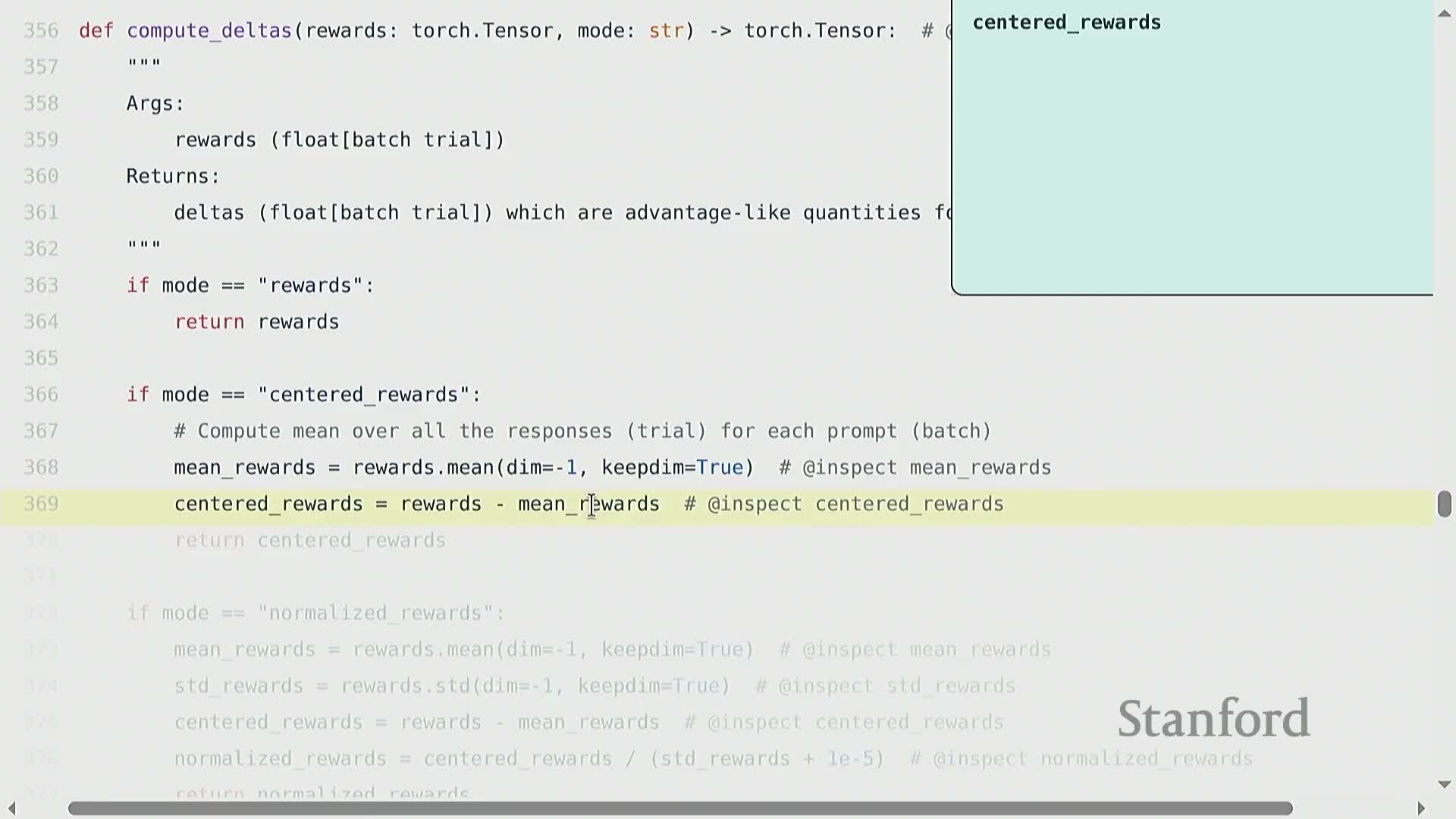

Computing deltas: centering, normalization, and optional max-only selection

- compute_deltas: converts raw rewards into scalar multipliers for gradient updates. Common choices include:

-

Raw rewards (no transformation).

-

Centering by subtracting per-prompt means.

-

Normalization by dividing by standard deviation (with epsilon for numerical stability).

-

Max-only: zero out any response that is not the batch maximum.

-

Raw rewards (no transformation).

- Practical effects:

-

Centering turns sparse 0/1 rewards into both positive and negative signals, so incorrect responses produce negative updates and correct ones positive—helps learning when positives are rare.

-

Normalization yields scale invariance to multiplicative reward changes.

-

Max-only selection enforces an all-or-nothing strategy to avoid rewarding trivial partial-credit solutions.

-

Centering turns sparse 0/1 rewards into both positive and negative signals, so incorrect responses produce negative updates and correct ones positive—helps learning when positives are rare.

- Takeaway:

- The chosen delta transformation profoundly affects update direction, stability, and sensitivity to reward scaling.

- The chosen delta transformation profoundly affects update direction, stability, and sensitivity to reward scaling.

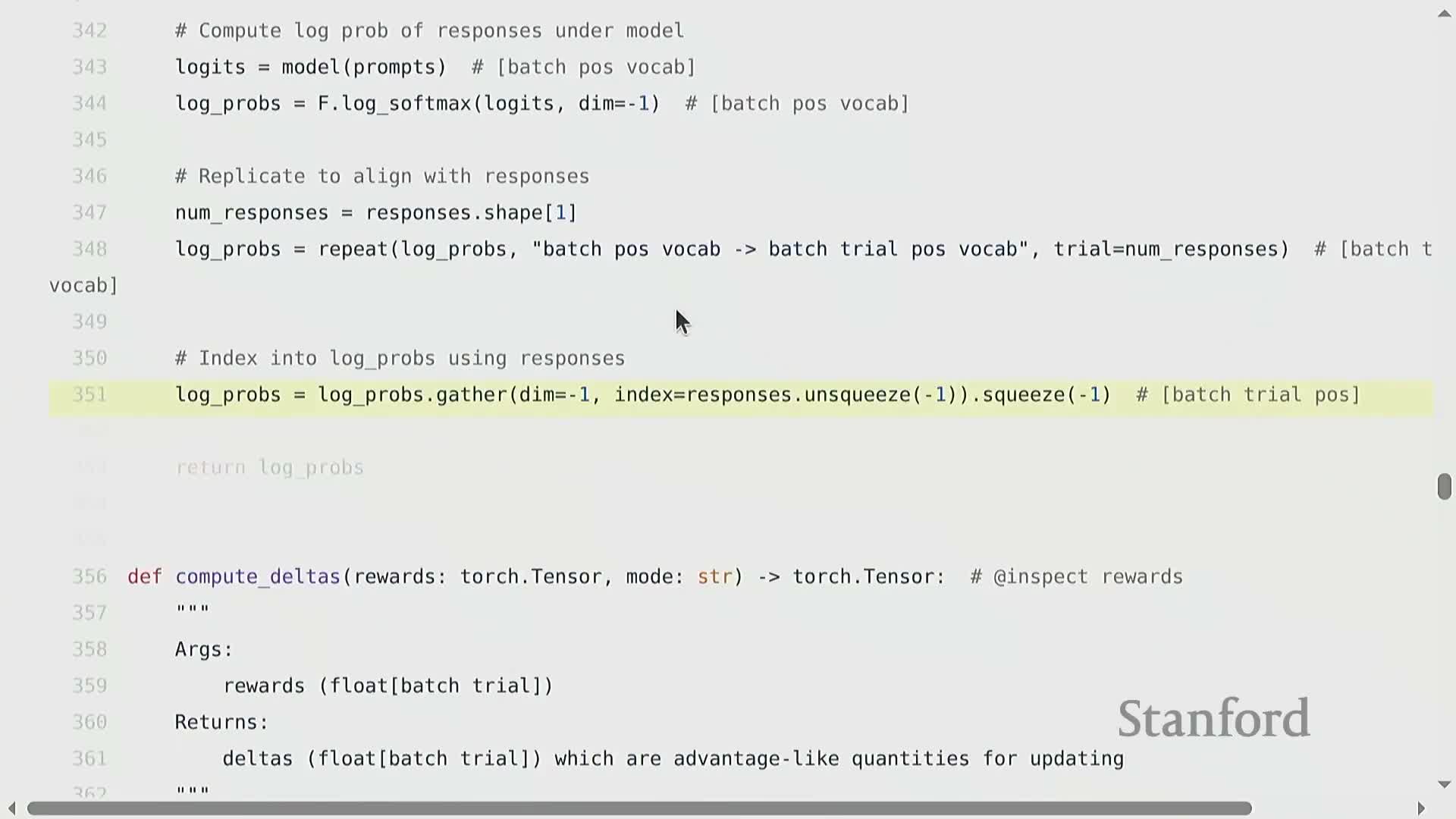

Log-probability extraction and naive policy-gradient loss computation

- Computing log-probabilities and loss:

- After sampling and scoring responses, compute the log-probability of each sampled token sequence by indexing model logits at the chosen token indices and summing or averaging across positions.

- After sampling and scoring responses, compute the log-probability of each sampled token sequence by indexing model logits at the chosen token indices and summing or averaging across positions.

- Naive policy-gradient loss (outcome reward regime):

- Broadcast the per-response delta to all positions for that response.

- Multiply the delta by the corresponding per-position log-probabilities and form the (negative) expected delta-weighted log-probability averaged across batch and trials.

- Broadcast the per-response delta to all positions for that response.

- Notes:

- This direct score-function estimator implements the Monte Carlo policy gradient for both non-autoregressive and autoregressive decodings.

-

Position broadcasting reflects the single-return-per-response assumption.

- The loss is modular: different delta computations (centered, normalized, clipped) can plug into the same gradient pipeline.

- This direct score-function estimator implements the Monte Carlo policy gradient for both non-autoregressive and autoregressive decodings.

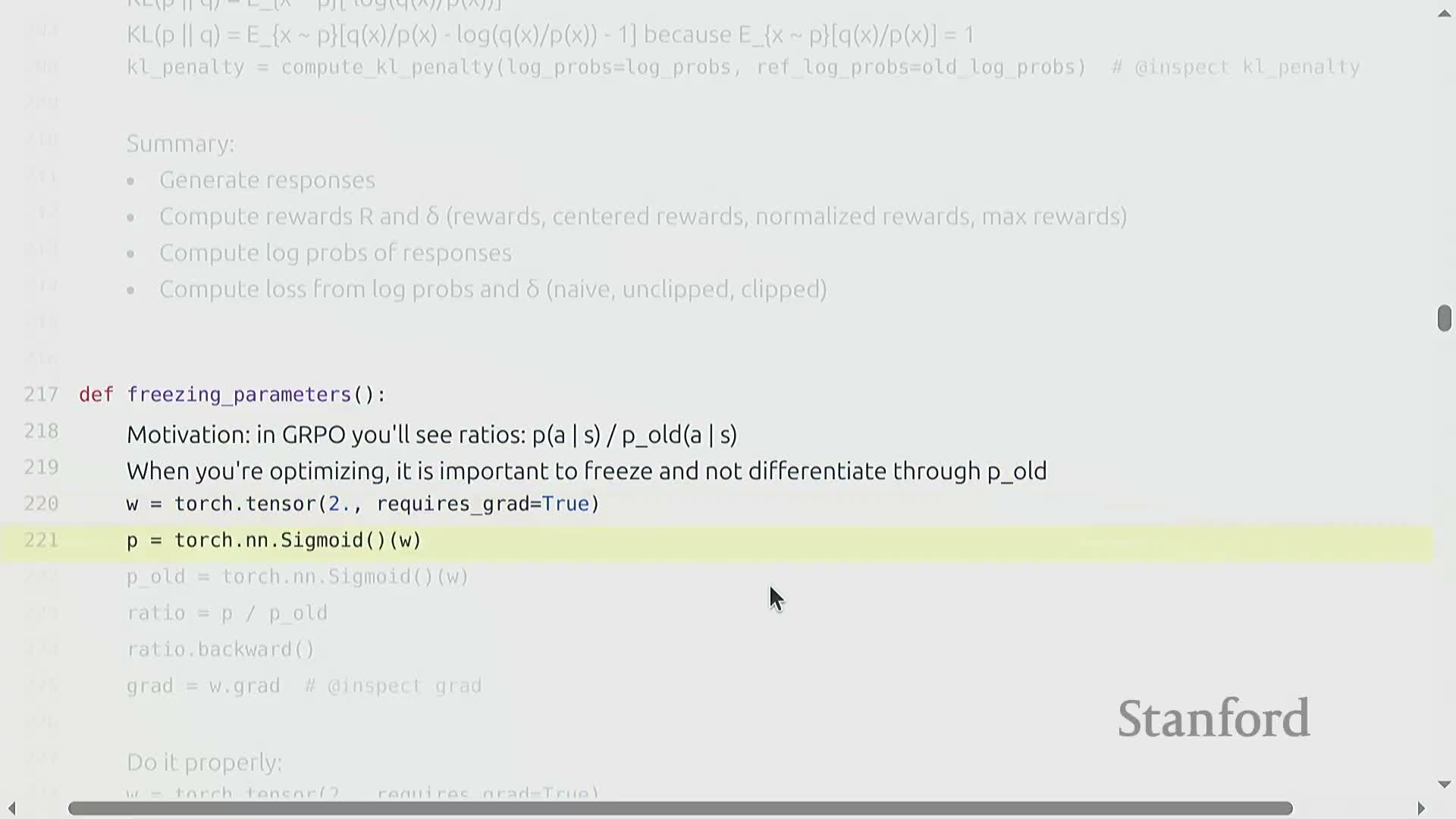

Freezing reference quantities (no-grad) and importance-ratio pitfalls

- Importance-weighted ratios (pi_theta / pi_old):

- Treat the denominator as a constant by disabling gradient flow through the old-policy computation.

- If you differentiate through both numerator and denominator, you can nullify gradients (e.g., ratio of identical parameterizations yields 1 and zero gradient), defeating learning.

- Treat the denominator as a constant by disabling gradient flow through the old-policy computation.

- Implementation guidance:

- Wrap old-policy log-probabilities or probabilities in no-grad contexts or cache scalar log-probabilities from a frozen checkpoint so the backward pass only propagates through the current policy.

- This engineering detail is critical for correctness when using PPO-style clipping or importance-weighted gradient estimators.

- Wrap old-policy log-probabilities or probabilities in no-grad contexts or cache scalar log-probabilities from a frozen checkpoint so the backward pass only propagates through the current policy.

Credit assignment and discounting considerations for outcome rewards

- Credit assignment challenges:

- Classical RL tools like discounting and bootstrapping are ambiguous when the reward is only available at episode end and many intermediate token decisions can matter.

- Discounting earlier tokens is not obviously beneficial because early strategic choices may determine later correctness more than later tokens themselves.

- Classical RL tools like discounting and bootstrapping are ambiguous when the reward is only available at episode end and many intermediate token decisions can matter.

- Practical approaches:

- Often smear credit across the entire response (broadcast final reward to all token positions).

- Or design process-level rewards if reliable intermediate signals exist.

- Often smear credit across the entire response (broadcast final reward to all token positions).

- Ongoing challenge:

- Designing effective credit-assignment mechanisms remains a core difficulty in sparse-reward LM tasks.

- Designing effective credit-assignment mechanisms remains a core difficulty in sparse-reward LM tasks.

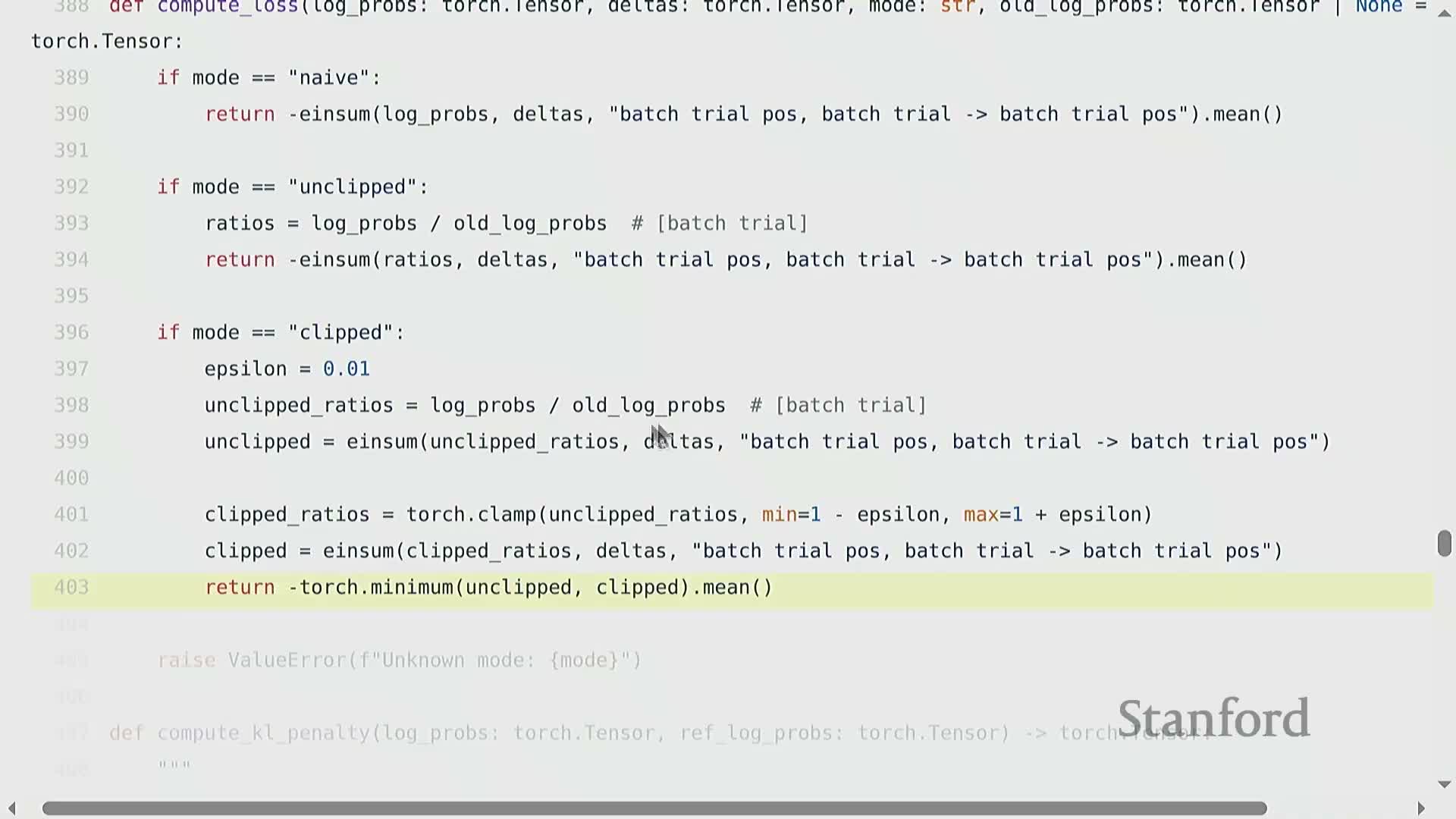

GRPO clipped objective and KL regularization

-

GRPO loss (group-relative, PPO-style):

- Compute importance-weighted ratios between current and old policies for sampled responses.

- Multiply ratios by deltas (reward/advantage variants).

-

Clip ratios to [1 − ε, 1 + ε] to bound update magnitudes and prevent destructive policy shifts.

- Take the minimum of the unclipped and clipped ratio-weighted deltas (with sign change to convert reward maximization into loss minimization).

- Compute importance-weighted ratios between current and old policies for sampled responses.

- Regularization:

- An auxiliary KL penalty between the current policy and a slowly updated reference policy provides additional stabilization.

- Unbiased but lower-variance estimators of KL are possible via algebraic rearrangement (e.g., q/p − log(q/p) − 1 forms).

- An auxiliary KL penalty between the current policy and a slowly updated reference policy provides additional stabilization.

- Purpose:

-

Clipping and KL regularization are practical mechanisms to stabilize policy updates in LM fine-tuning contexts.

-

Clipping and KL regularization are practical mechanisms to stabilize policy updates in LM fine-tuning contexts.

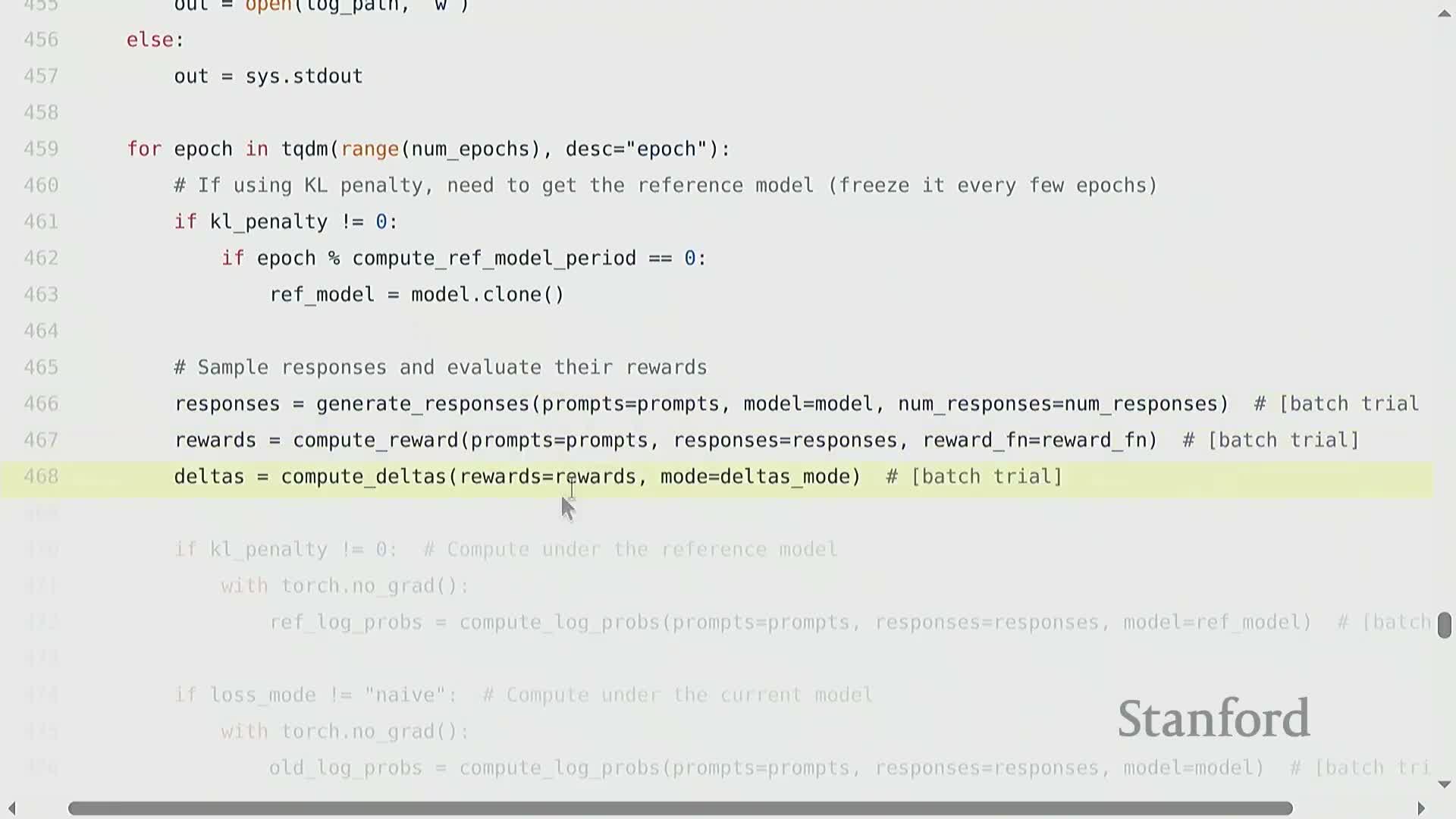

Algorithm components, inner/outer loop structure, and computational workflow

- Typical training loop structure:

- Outer loop: generate a fresh batch of responses (inference rollouts).

- Inner loop: perform multiple gradient steps on that static set of rollouts to amortize expensive sampling costs.

- Outer loop: generate a fresh batch of responses (inference rollouts).

- Key components:

-

Current policy being trained.

-

Frozen old policy used to compute importance ratios for clipping.

-

Slower-moving reference policy for KL regularization (updated less frequently).

-

Current policy being trained.

- Practical considerations:

- Cache log-probabilities from the rollout stage to avoid recomputing frozen-model outputs and reduce compute/memory needs.

- Architecting inference workers, checkpointing, and distributed pipelines is a major engineering concern beyond the scalar algorithmic choices.

- The inner/outer loop design reflects a trade-off between sample efficiency and inference cost at scale.

- Cache log-probabilities from the rollout stage to avoid recomputing frozen-model outputs and reduce compute/memory needs.

Why a separate KL reference vs. old policy and initialization considerations

- Role of a slowly updated reference model for KL regularization:

-

Decouples the long-term regularization target from the short-term importance-ratio stabilization provided by the old policy.

- Helps define a stable optimization objective over inner-loop updates.

-

Decouples the long-term regularization target from the short-term importance-ratio stabilization provided by the old policy.

- Practical notes:

- If the KL target were the immediately previous policy (changing on the same timescale), regularization would shift too rapidly and could undermine convergence.

- Common practices: use a frozen checkpoint or periodic parameter copies as a constant regularization anchor; compute pi_old quantities from cached log-probabilities.

- Even when pi_old equals the current policy in initial iterations, valid updates occur because pi_old is treated as a constant in gradient computations.

- If the KL target were the immediately previous policy (changing on the same timescale), regularization would shift too rapidly and could undermine convergence.

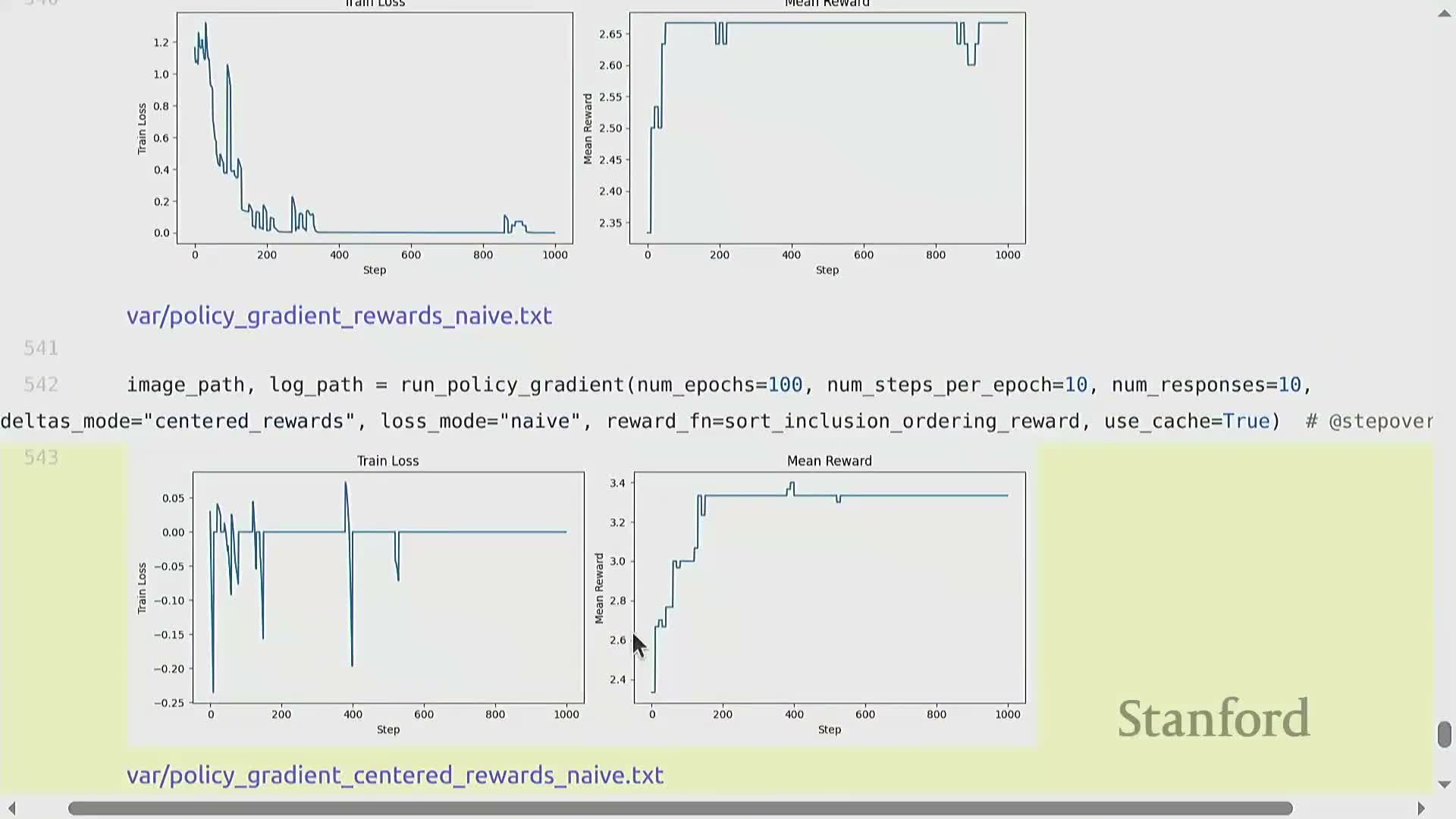

Empirical sorting-task experiments and learning curve interpretation

- Empirical observations on the toy sorting task:

-

Centered-reward updates often yield modest mean-reward improvements, pushing the policy away from lower-reward responses within a prompt cohort.

- Limitations:

- If all sampled responses for a prompt have identical rewards, centered deltas become zero and produce no update for that batch.

-

Loss curves can be misleading because the data distribution changes as the policy evolves.

- If all sampled responses for a prompt have identical rewards, centered deltas become zero and produce no update for that batch.

-

Centered-reward updates often yield modest mean-reward improvements, pushing the policy away from lower-reward responses within a prompt cohort.

- Monitoring recommendations:

- Track reward metrics on held-out prompts or regenerate rollouts to assess true progress.

- Experiments illustrate sensitivity to reward design, delta transformations, sampling variance, and the need for careful hyperparameter tuning.

- Track reward metrics on held-out prompts or regenerate rollouts to assess true progress.

Conclusions: promise of RL for LMs and scaling challenges

- Why use RL for LMs:

-

Optimizes behaviors that exceed imitation-limited supervised data by directly optimizing measurable objectives when verifiable rewards exist.

- Powerful for improving LM performance on tasks with quantifiable outcomes.

-

Optimizes behaviors that exceed imitation-limited supervised data by directly optimizing measurable objectives when verifiable rewards exist.

- Persistent challenges:

-

Sparse and delayed rewards.

- High variance in Monte Carlo estimators.

-

Reward-design vulnerabilities (hackability/exploitation).

- Complex credit assignment across long token sequences.

-

Sparse and delayed rewards.

- Systems-level complexity:

- Building scalable RL for LMs adds engineering burden beyond pretraining: inference cost, multi-model orchestration (policy, old policy, reference, reward models), and distributed execution must be managed.

- Building scalable RL for LMs adds engineering burden beyond pretraining: inference cost, multi-model orchestration (policy, old policy, reference, reward models), and distributed execution must be managed.

- Outlook:

- Continued research on reward specification, variance reduction, and system-level infrastructure is necessary to realize RL’s potential for large-scale language-model improvement.

- Continued research on reward specification, variance reduction, and system-level infrastructure is necessary to realize RL’s potential for large-scale language-model improvement.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: