Karpathy Series - Let's build the GPT Tokenizer

- Tokenization is a necessary and often problematic preprocessing step for large language models

- A naive character-level tokenizer maps each character to a unique integer and feeds embeddings to the Transformer

- Modern LLM tokenizers operate on subword or byte-level chunks and are typically constructed with algorithms like byte-pair encoding

- Tokenization causes many surprising application-level behaviors in LLMs

- Interactive tokenizer visualizers expose token boundaries, whitespace handling, and model-specific token IDs

- Numeric strings are tokenized inconsistently and arbitrarily which impairs arithmetic and digit-level tasks

- Tokenization is case-sensitive and context-sensitive, causing identical surface strings to map to different tokens

- Poor tokenization of indentation and repeated whitespace makes code inefficient to represent and reduces effective context

- Improvements in tokenization (larger vocabulary and better whitespace grouping) materially improve model performance on code and length of context

- Strings in Python are sequences of Unicode code points; ord() reveals codepoint integers but using them directly as tokens is problematic

- Byte encodings (UTF-8/16/32) transform code points into byte streams; UTF-8 is the ubiquitous variable-length choice

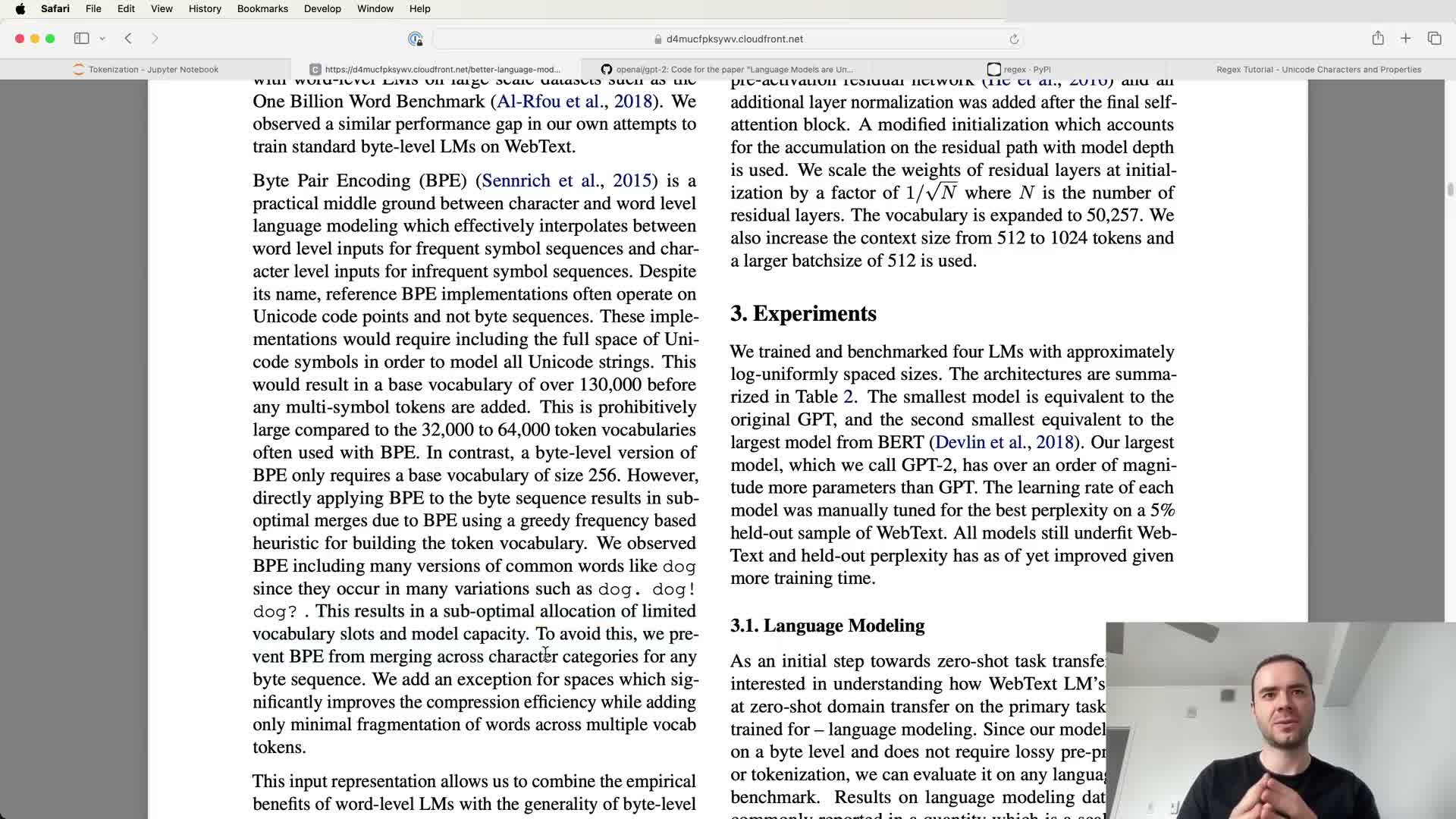

- Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) compresses byte or character sequences by iteratively merging frequent adjacent pairs into new tokens

- Implementing BPE requires counting adjacent pair frequencies and applying pair replacements; practical code iterates until the target vocab size

- Training a tokenizer on larger corpora and choosing the merge count determines compression ratio and vocabulary composition

- The tokenizer is a separate preprocessing artifact with its own training set and resulting encode/decode functions

- Decoding tokens to text concatenates token byte sequences and decodes via UTF-8 with error handling

- Encoding text into tokens applies merges in merge-order and must respect merge eligibility and order constraints

- Real-world tokenizers add manual heuristics to BPE: regex chunking prevents semantically bad merges

- Regex-based chunking contains many subtle language and Unicode issues (apostrophes, case, whitespace handling)

- The inference code for GPT-2’s tokenizer (encoder.py) implements BPE application but the original training code was not released

Tokenization is a necessary and often problematic preprocessing step for large language models

Tokenization is the process that translates raw text strings into discrete token sequences that language models operate on — it converts text into integer indices used to look up trainable embedding vectors.

Because tokenization defines the model’s input units, it introduces subtle failure modes and distribution mismatches that often explain odd model behavior. What looks like an architecture bug frequently traces back to tokenizer choices, so practitioners must understand tokenization in detail to:

- Diagnose errors across multilingual and special-character inputs

- Design token vocabularies and preprocessing pipelines

- Evaluate tokenization as a distinct part of the data pipeline, engineered and tested independently of model architecture

Tokenization therefore requires careful engineering, monitoring, and evaluation rather than being an incidental preprocessing step.

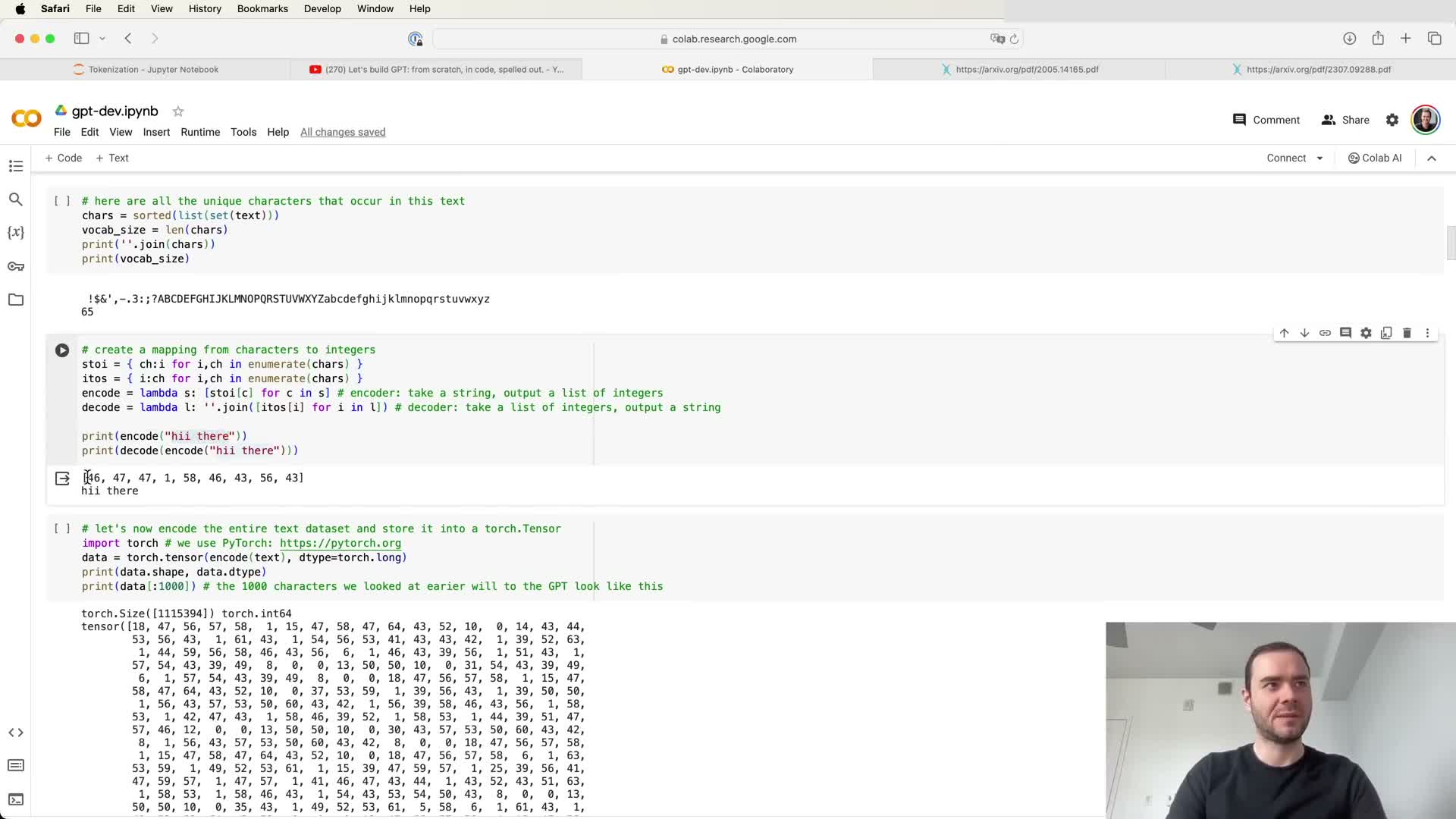

A naive character-level tokenizer maps each character to a unique integer and feeds embeddings to the Transformer

A character-level tokenizer builds a vocabulary of the individual characters observed in the corpus and maps each character to an integer token ID.

- Every character in a string becomes one token; the model learns a trainable embedding row per character that feeds into the Transformer.

- Pros: simple, stable, and pedagogically useful.

- Cons: highly inefficient for long-range dependencies because sequence lengths are large while embeddings/softmax sizes remain small — this forces long context windows and poor compression.

Character tokenizers can work for small-domain tasks, but they lack the compression needed to scale to web-scale corpora without prohibitive context lengths.

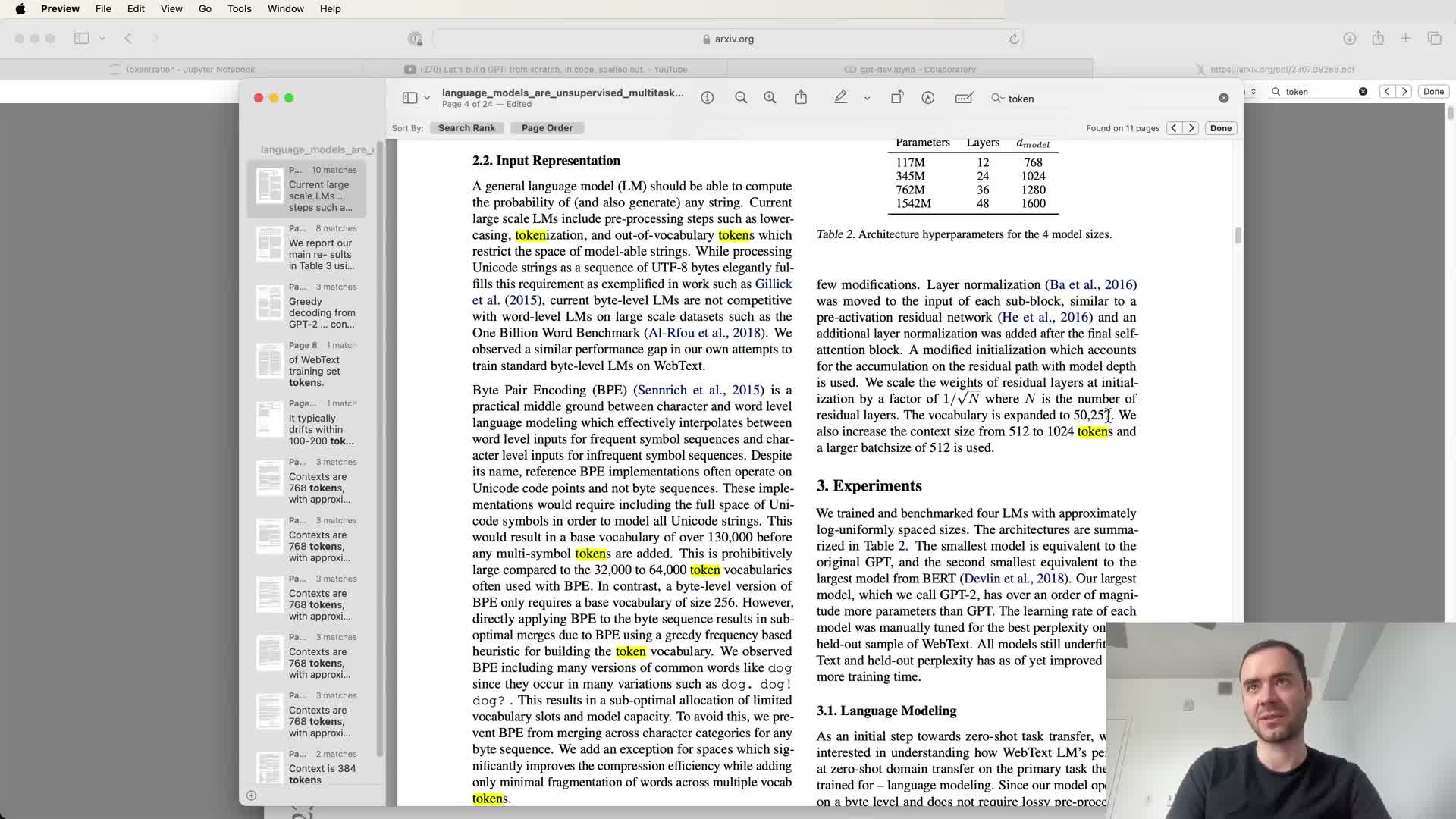

Modern LLM tokenizers operate on subword or byte-level chunks and are typically constructed with algorithms like byte-pair encoding

State-of-the-art models use variable-length subword chunks or byte-level units rather than pure character tokenizers, often built with algorithms like byte-pair encoding (BPE).

-

BPE iteratively merges frequently co-occurring token pairs to trade vocabulary size against sequence length.

- Tokens are the atomic units of attention and context, so vocabulary size and chunking directly determine how much raw text a model can attend to and how it must generalize.

- Papers (e.g., GPT-2) report concrete vocabulary and context settings (for example, ~50k tokens and 1,024 token context) because these numbers materially affect model behavior.

Choosing chunking strategy and vocabulary size is therefore fundamental to model capacity and efficiency.

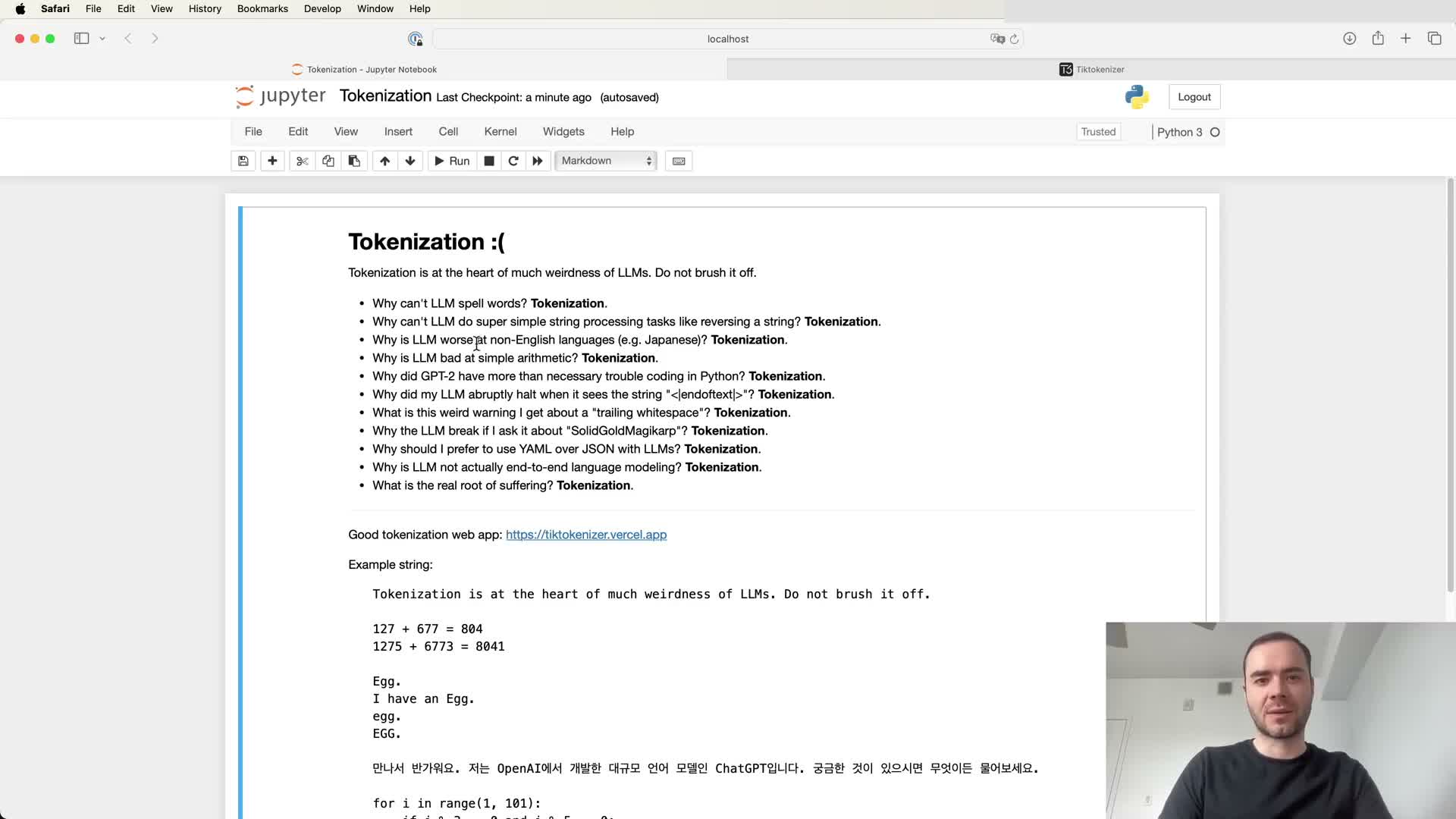

Tokenization causes many surprising application-level behaviors in LLMs

Many LLM quirks — spelling issues, weak non-English performance, odd JSON/YAML outputs, trailing-space artifacts — often originate in tokenization rather than the Transformer itself.

- Tokenization determines what the model treats as atomic units, which affects training frequency of tokens and the model’s generalization burden.

- Because tokenizers are a preprocessing stage trained separately and can differ across datasets/models, they are a frequent source of domain mismatch and hard-to-diagnose bugs.

- Diagnosing these issues typically requires inspection of token boundaries and vocabularies rather than only model weights or architecture.

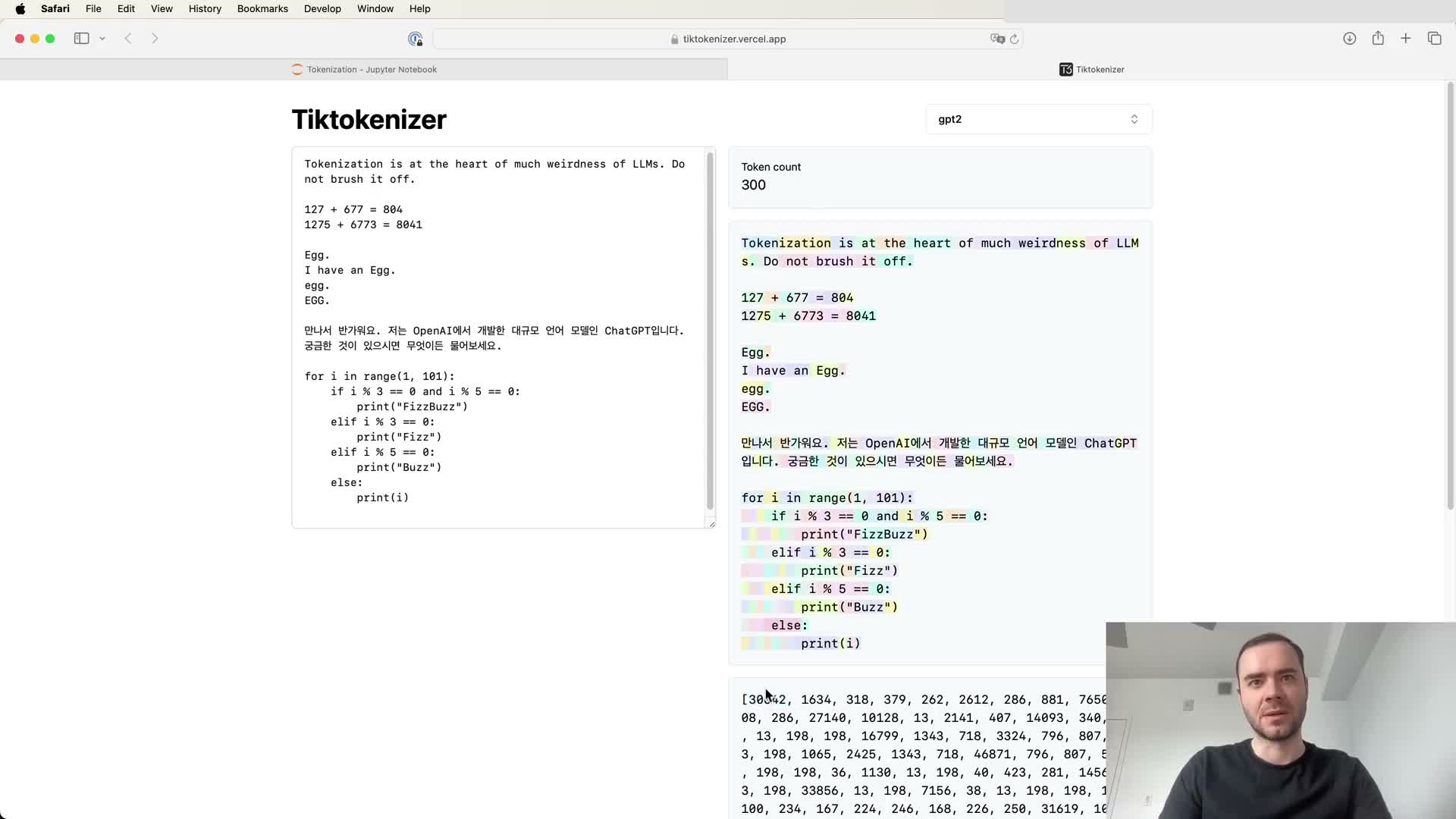

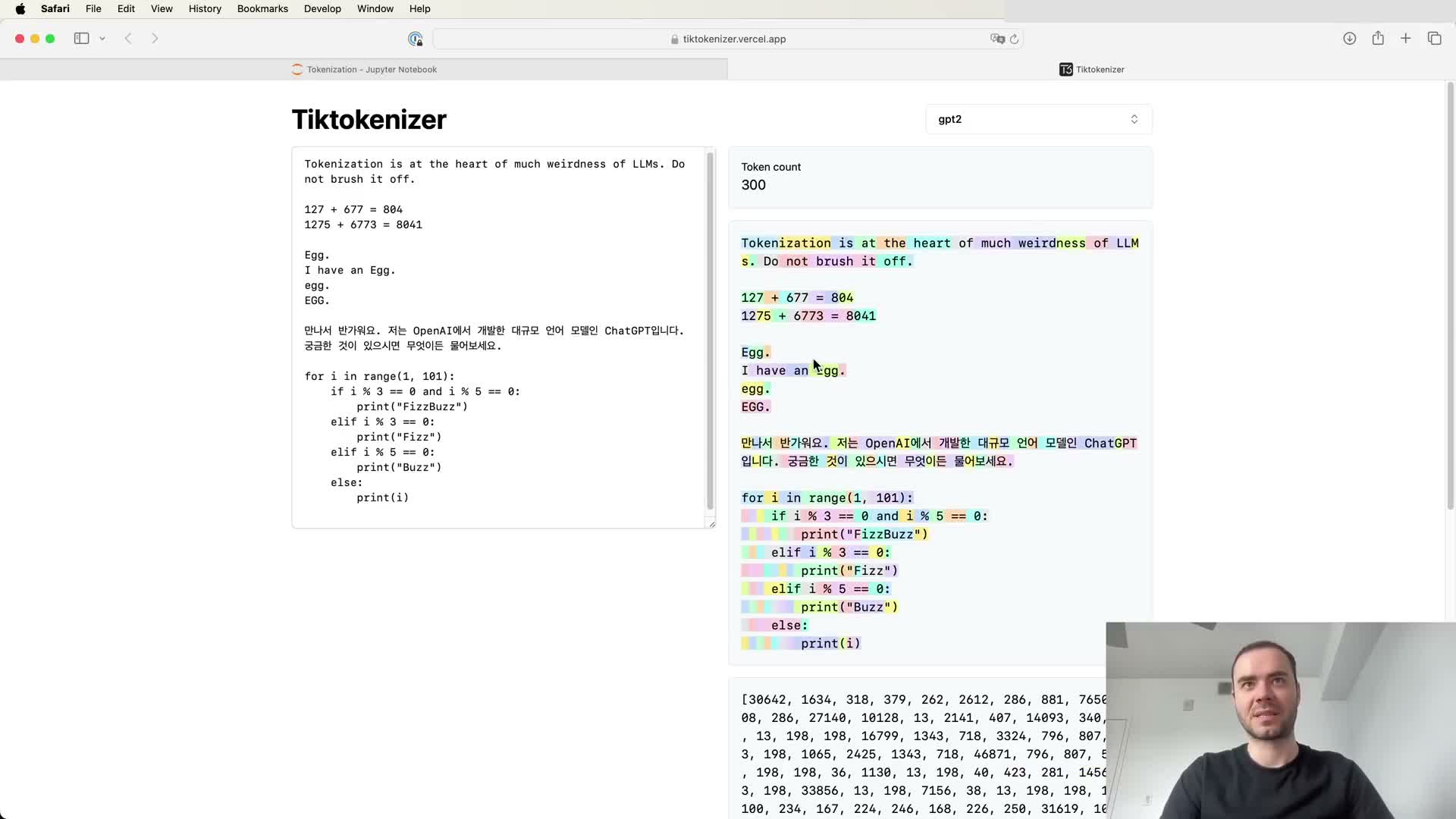

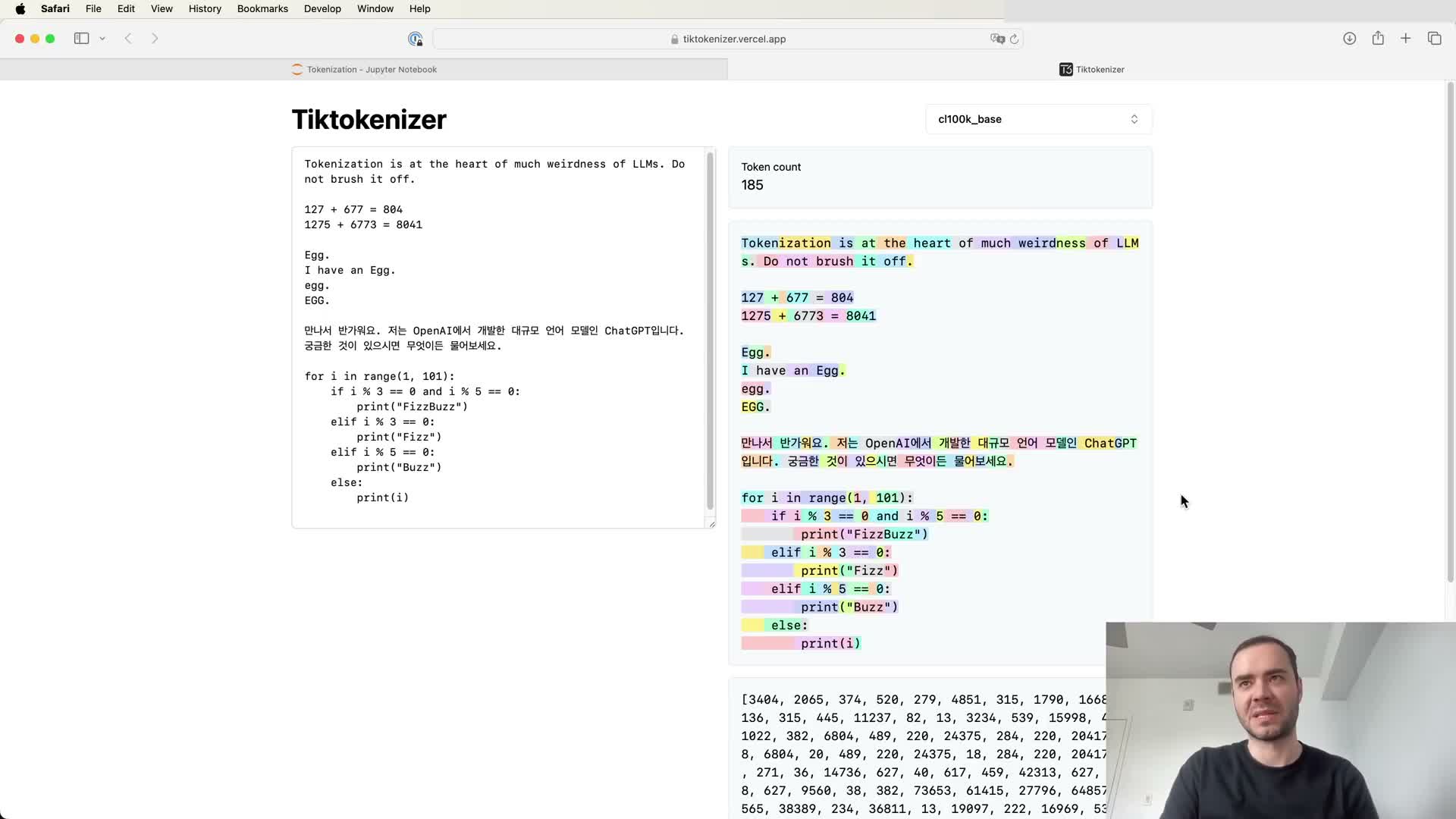

Interactive tokenizer visualizers expose token boundaries, whitespace handling, and model-specific token IDs

Browser-based tokenizer visualizers are practical debugging tools: they split text into colored, indexed tokens and reveal implementation details.

What these tools show and why they matter:

- Whether whitespace is part of tokens (e.g., “ space+word” vs “word”)

- Token IDs for punctuation, digits, and other glyphs

- Differences in segmentation between tokenizers (e.g., GPT-2 vs GPT-4) for the same input

Uses: prompt debugging, measuring token counts, and evaluating tokenizer efficiency for target domains like code or multilingual text. Visual inspection often reveals why identical surface forms are treated differently depending on position, surrounding whitespace, or case.

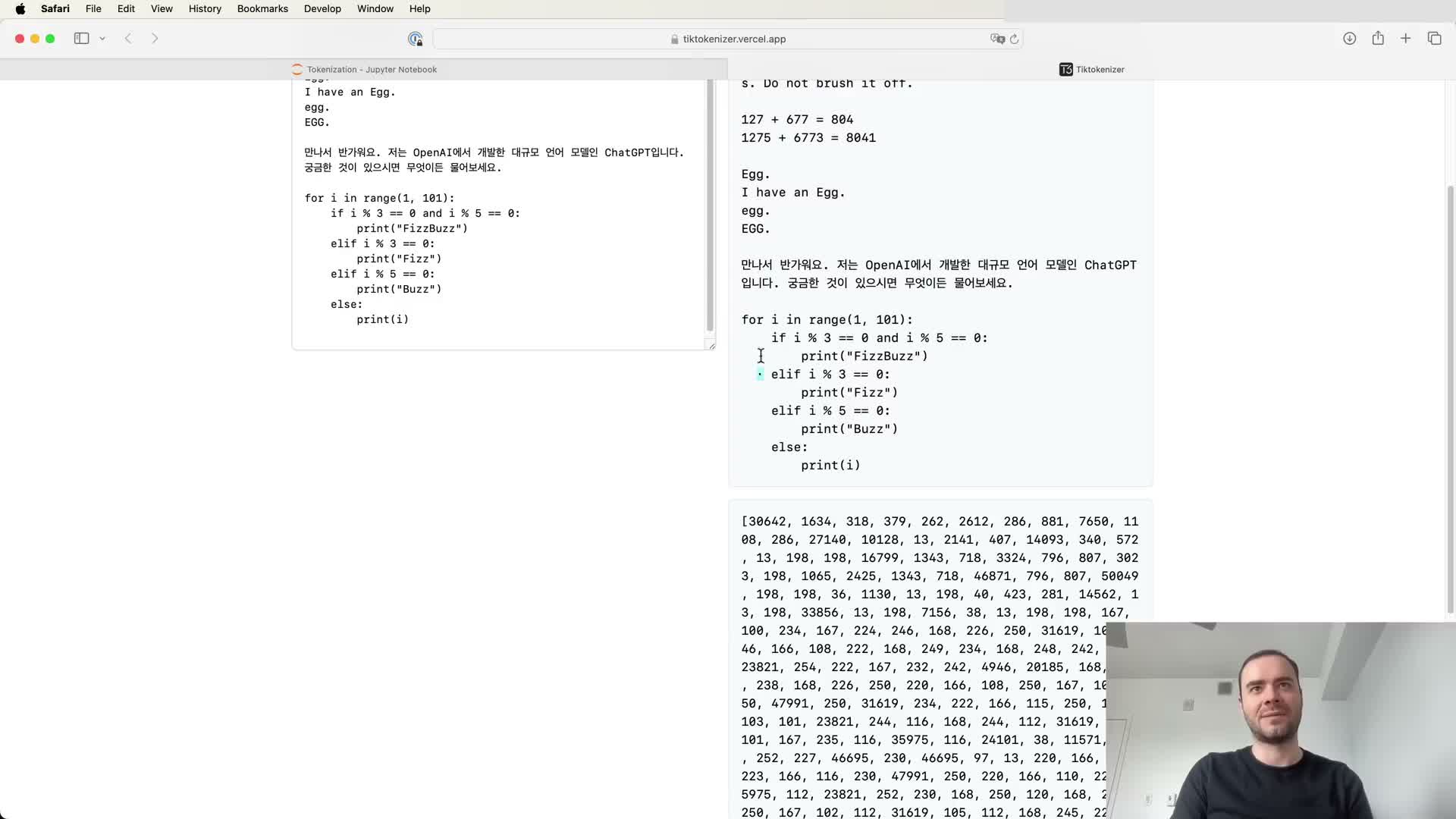

Numeric strings are tokenized inconsistently and arbitrarily which impairs arithmetic and digit-level tasks

There is no canonical way to tokenize numbers across models: some numeral sequences are a single token, others split into several tokens, determined by training-time merges rather than numeric semantics.

- This arbitrary segmentation complicates digit-oriented tasks (digit manipulation, arithmetic, exact string ops) because the model lacks a consistent per-digit representation.

- When correctness requires digit-level manipulation, you often must force explicit character-level handling in prompts or preprocessing to ensure predictable tokenization.

Tokenization is case-sensitive and context-sensitive, causing identical surface strings to map to different tokens

Tokenizers often treat case and surrounding whitespace as part of token identity: uppercase vs lowercase or tokens at sentence starts vs after whitespace can map to different IDs.

- The same letters can have different token IDs depending on case and whether a leading space is present.

- Consequence: the model may need separate embeddings or must rely on parameter-sharing to associate variants, increasing data requirements and fragmentation.

- Mitigation: normalize or augment training/prompt data to reduce rare-token fragmentation and make variants more consistent.

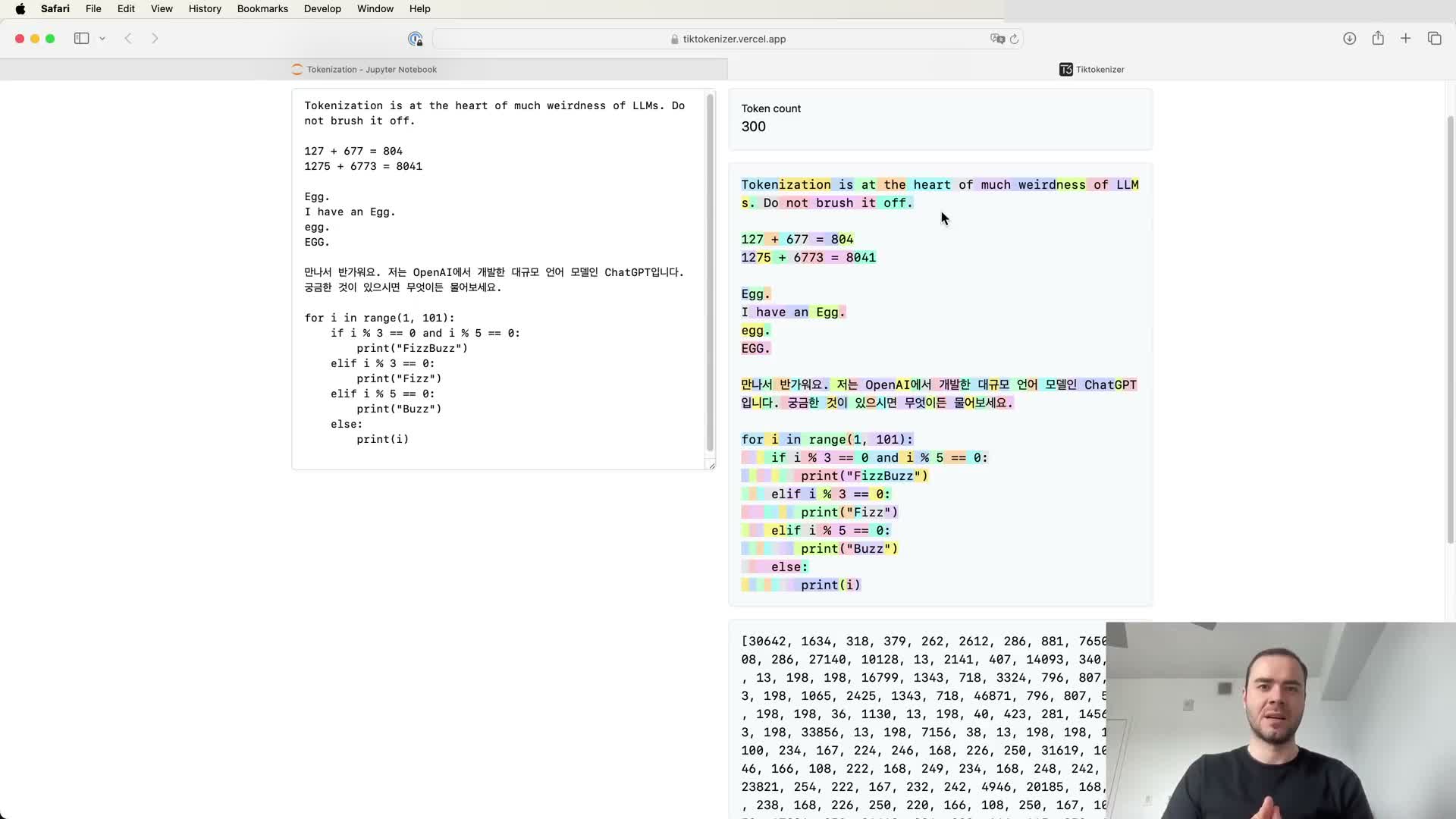

Poor tokenization of indentation and repeated whitespace makes code inefficient to represent and reduces effective context

When a tokenizer treats each space as a distinct token (as older GPT-2 tokenizers did), whitespace-sensitive formats like Python become token-bloat heavy and consume large parts of the model’s fixed context window.

- Denser tokenizers that group repeated spaces or indentation into single tokens substantially improve effective context utilization.

- For code modeling, grouping common indentation patterns into tokens is a practical optimization that increases the amount of useful code the model can attend to without changing the architecture.

Improvements in tokenization (larger vocabulary and better whitespace grouping) materially improve model performance on code and length of context

Increasing vocabulary size (e.g., from ~50k to ~100k) while engineering merges that group common whitespace and indentation can reduce sequence length and densify inputs.

- Effect: the same Transformer architecture can attend to more raw characters per context length, improving tasks like code completion.

- Trade-off: larger vocabularies increase embedding table size and softmax cost at the output, so vocabulary size is a hyperparameter balancing compression vs. parameter overhead.

- Practical gain comes from careful tokenizer design and training on representative corpora (including code) to learn useful merges.

Strings in Python are sequences of Unicode code points; ord() reveals codepoint integers but using them directly as tokens is problematic

Python strings represent text as immutable sequences of Unicode code points (roughly 150k code points across scripts). The built-in ord() maps a single character to its Unicode code point integer.

- Using code point integers directly as tokens creates a very large, brittle vocabulary (and is sensitive to Unicode updates).

- Raw code points also fail to provide sequence compression or control over vocabulary density, motivating the use of byte encodings and subword schemes instead.

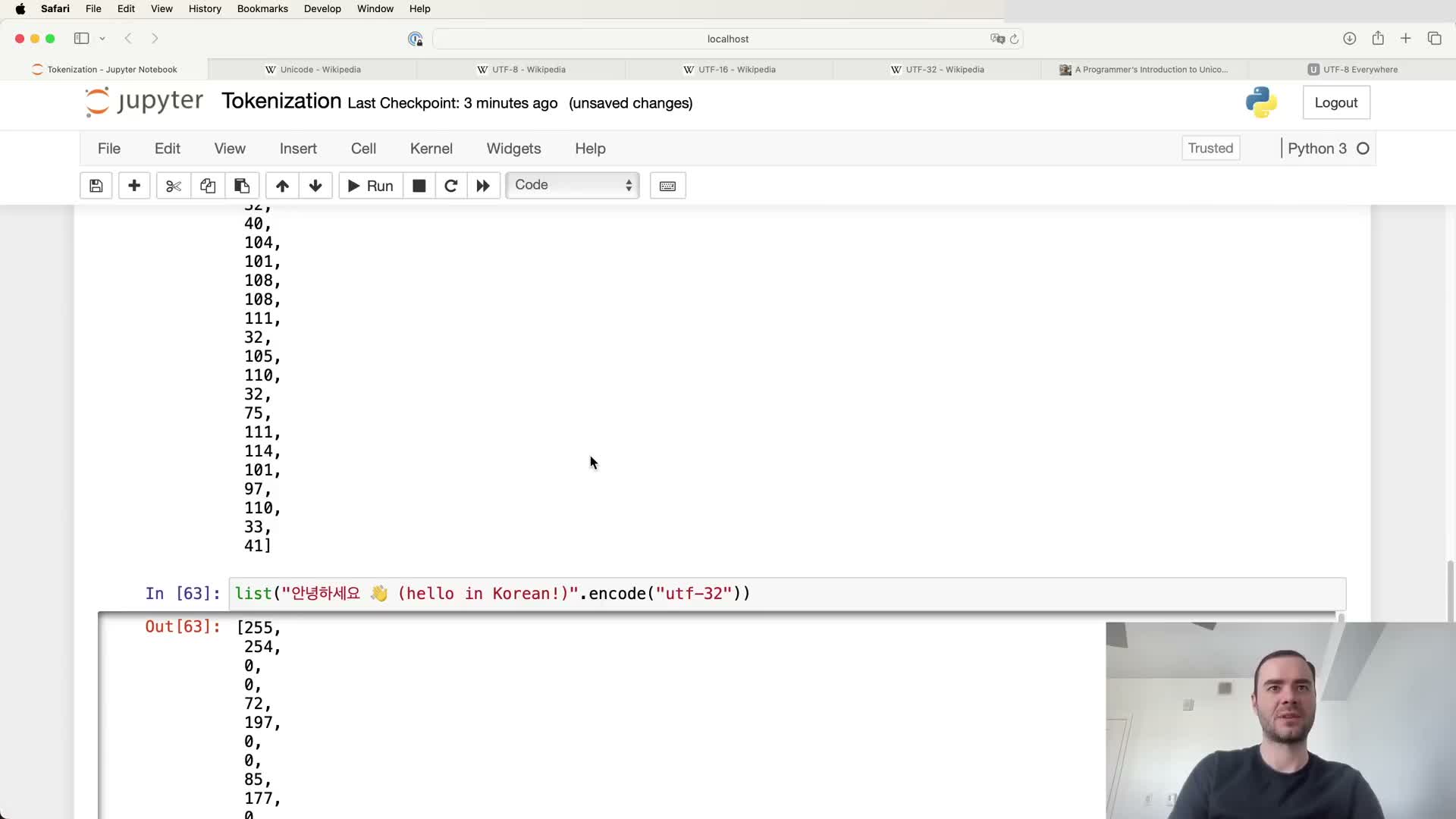

Byte encodings (UTF-8/16/32) transform code points into byte streams; UTF-8 is the ubiquitous variable-length choice

Unicode has multiple binary encodings: UTF-8 (1–4 bytes, ASCII-compatible), UTF-16 (2 or 4 bytes), and UTF-32 (fixed 4 bytes).

- UTF-8 is the web’s de facto standard because it is compact for ASCII and backward-compatible.

- Encoding text to UTF-8 yields a sequence of bytes that can serve as a base representation for tokenization.

- But treating raw bytes as tokens gives a tiny vocabulary (256) and very long sequences, which is inefficient for autoregressive models with limited attention — so further compression (e.g., BPE) is required.

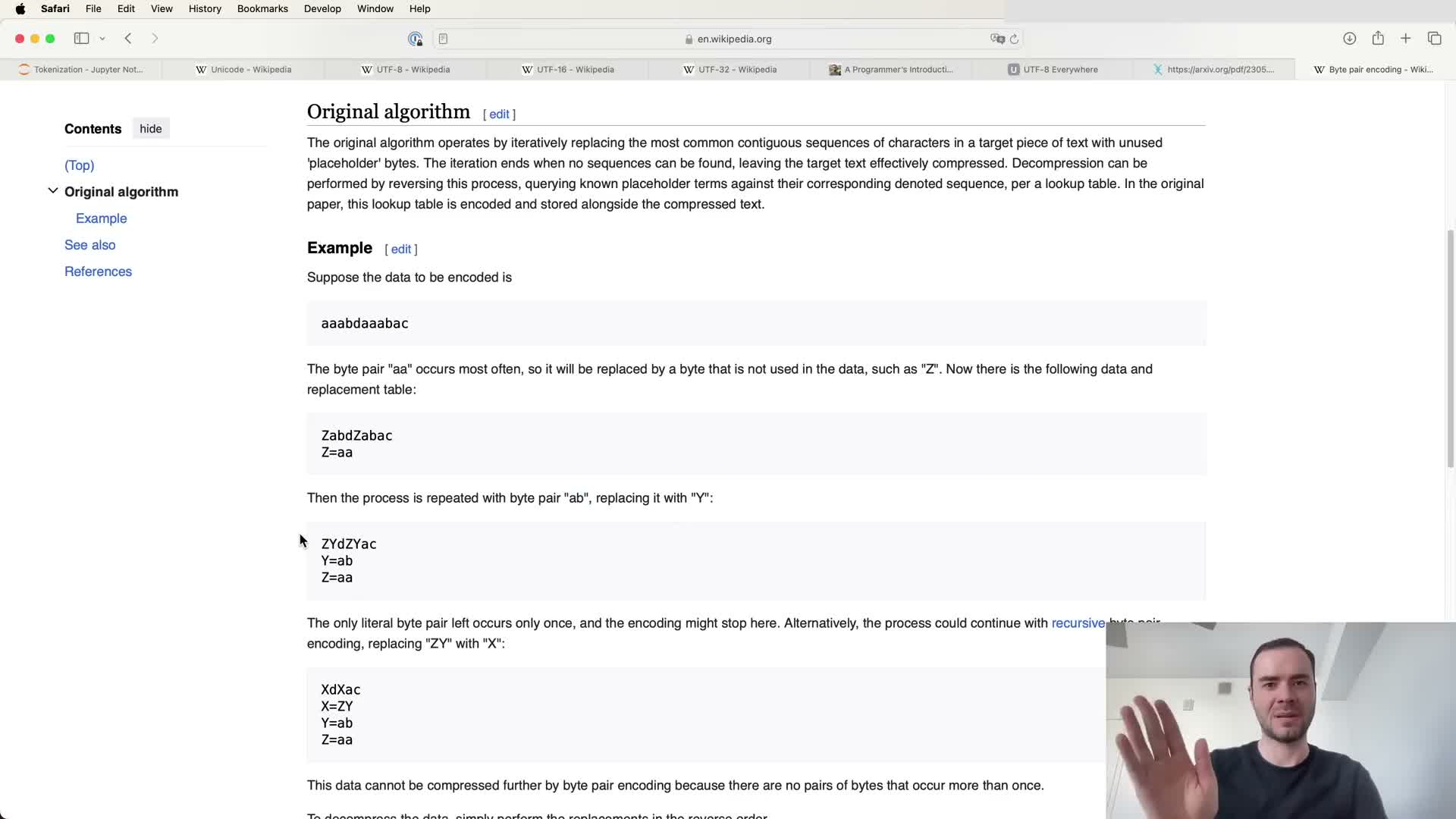

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) compresses byte or character sequences by iteratively merging frequent adjacent pairs into new tokens

Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) starts from a base vocabulary (bytes or observed code points) and repeatedly merges the most frequent adjacent token pairs to create new tokens.

- Compute frequencies of adjacent token pairs across the corpus.

- Select the most frequent pair and create a new token representing their concatenation.

- Replace all occurrences of that pair with the new token, incrementing vocabulary size by one and reducing average sequence length.

This loop continues until a target vocabulary size is reached, producing a merges table and a token-to-bytes mapping used for deterministic encoding/decoding. BPE provides a tunable trade-off between vocabulary size and sequence compression.

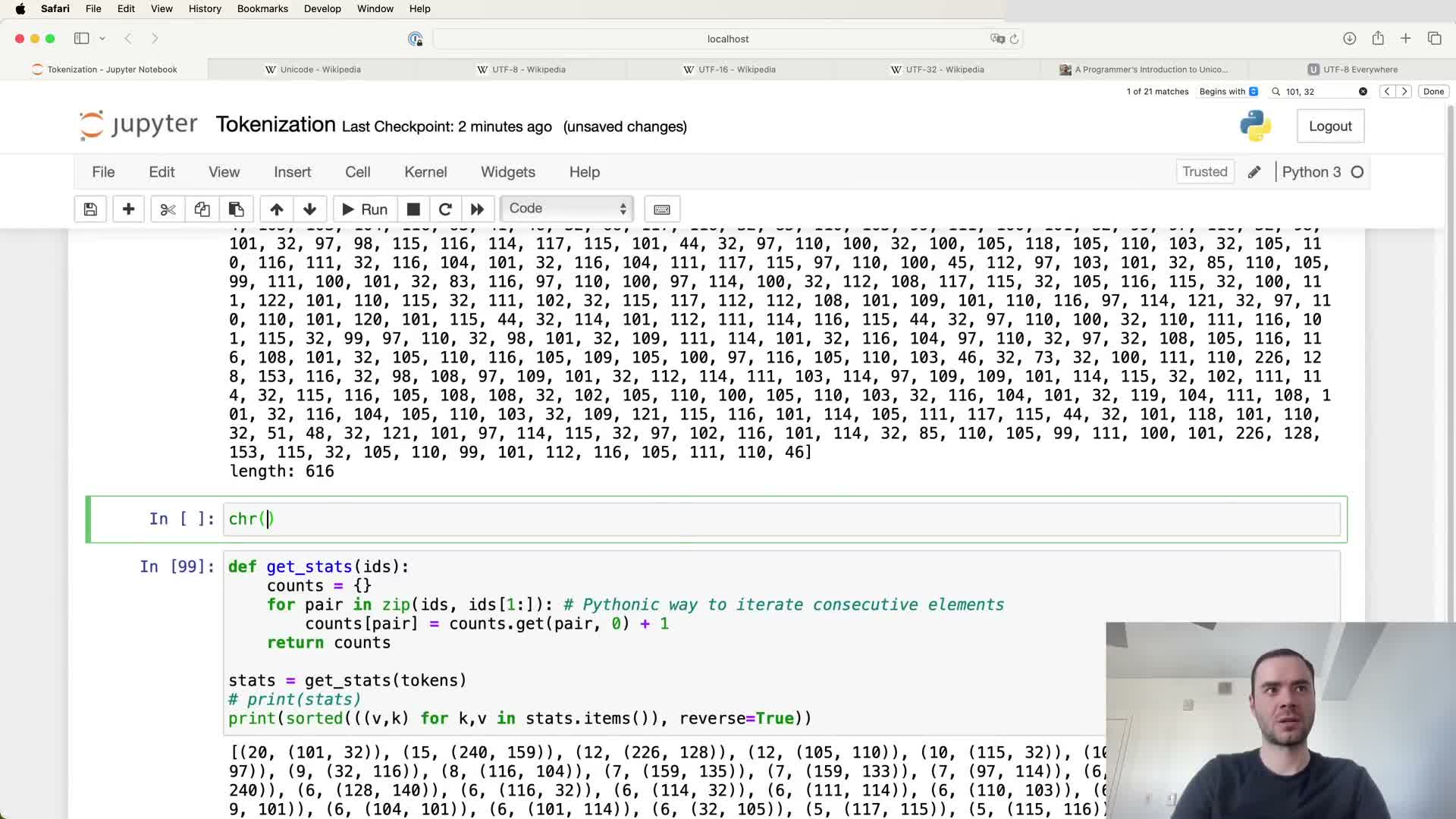

Implementing BPE requires counting adjacent pair frequencies and applying pair replacements; practical code iterates until the target vocab size

A BPE training loop operates as follows:

- Count statistics of all consecutive token pairs in the corpus.

- Select the most frequent pair.

- Mint a new token identifier for that pair and replace every occurrence in the corpus.

- Update pair statistics and repeat until the desired number of merges (vocabulary size) is reached.

Implementation notes and pitfalls:

- Use robust pair counting and efficient data structures to avoid quadratic costs.

- Perform careful in-place replacement to avoid index errors when spans overlap.

- Track merges as parent→children mappings to support later encoding and decoding.

The final merges list plus the base token mapping form the tokenizer able to compress inputs deterministically using the learned merge sequence.

Training a tokenizer on larger corpora and choosing the merge count determines compression ratio and vocabulary composition

When BPE is trained on longer, representative corpora, pair frequencies stabilize and more useful merges are learned.

- Increasing merges produces larger vocabularies and greater compression; the merges dictionary forms a hierarchical forest of binary merges enabling encoding/decoding by concatenation.

- The compression ratio scales with the number of merges and corpus characteristics, so vocabulary size is tuned to balance embedding/softmax cost against available context length.

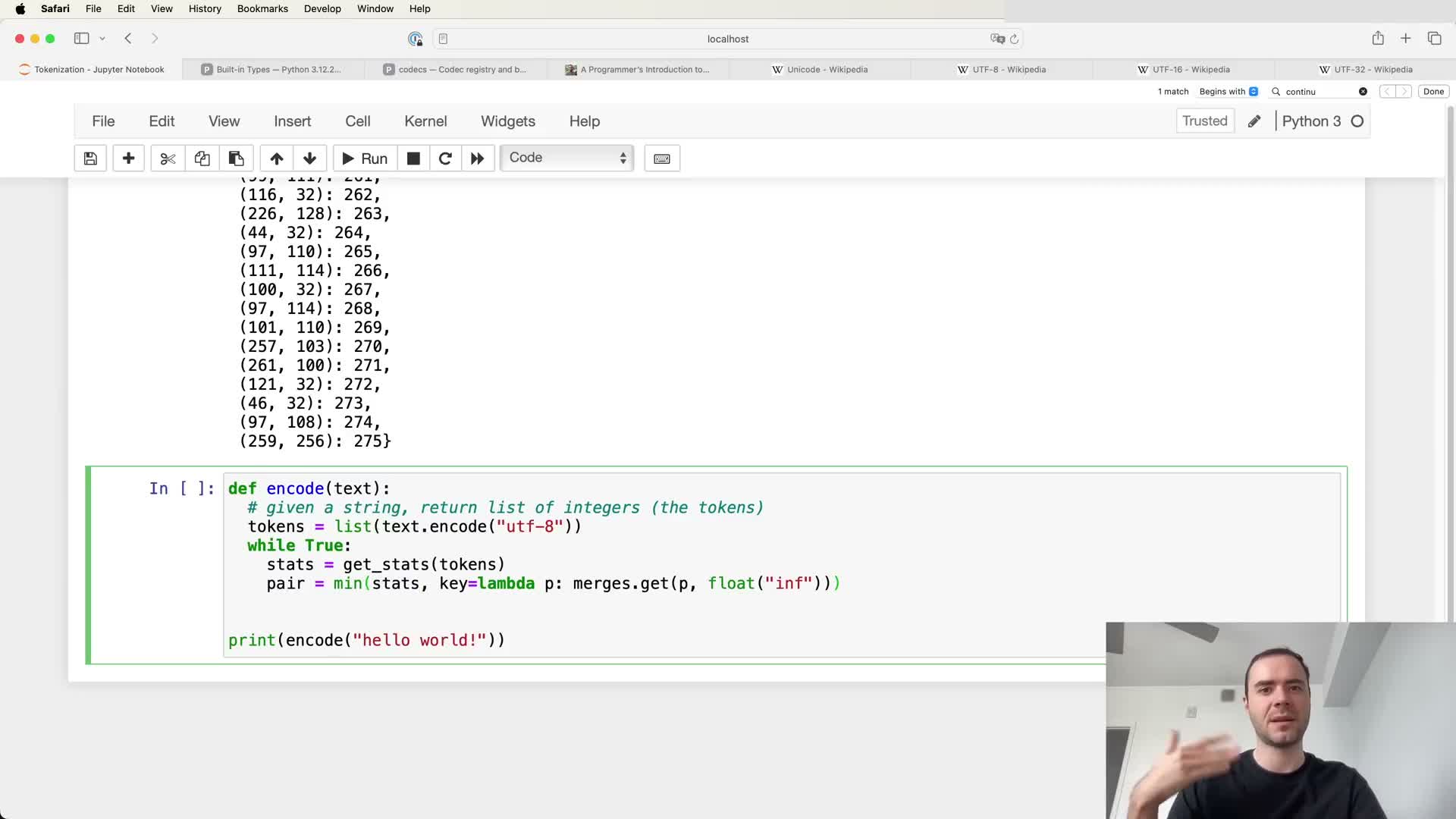

The tokenizer is a separate preprocessing artifact with its own training set and resulting encode/decode functions

A trained tokenizer is an independent, serializable artifact that maps raw text to token IDs and back.

- Typical outputs: the base token-to-bytes map (vocab) and the merges table.

- Tokenizers are usually trained beforehand (possibly on a different dataset than the LM corpus) and applied once to the LM training corpus to produce token streams stored for model training.

Because tokenizers determine the effective distribution the model sees, tokenizer choices materially affect the downstream model and must be versioned and validated as separate artifacts.

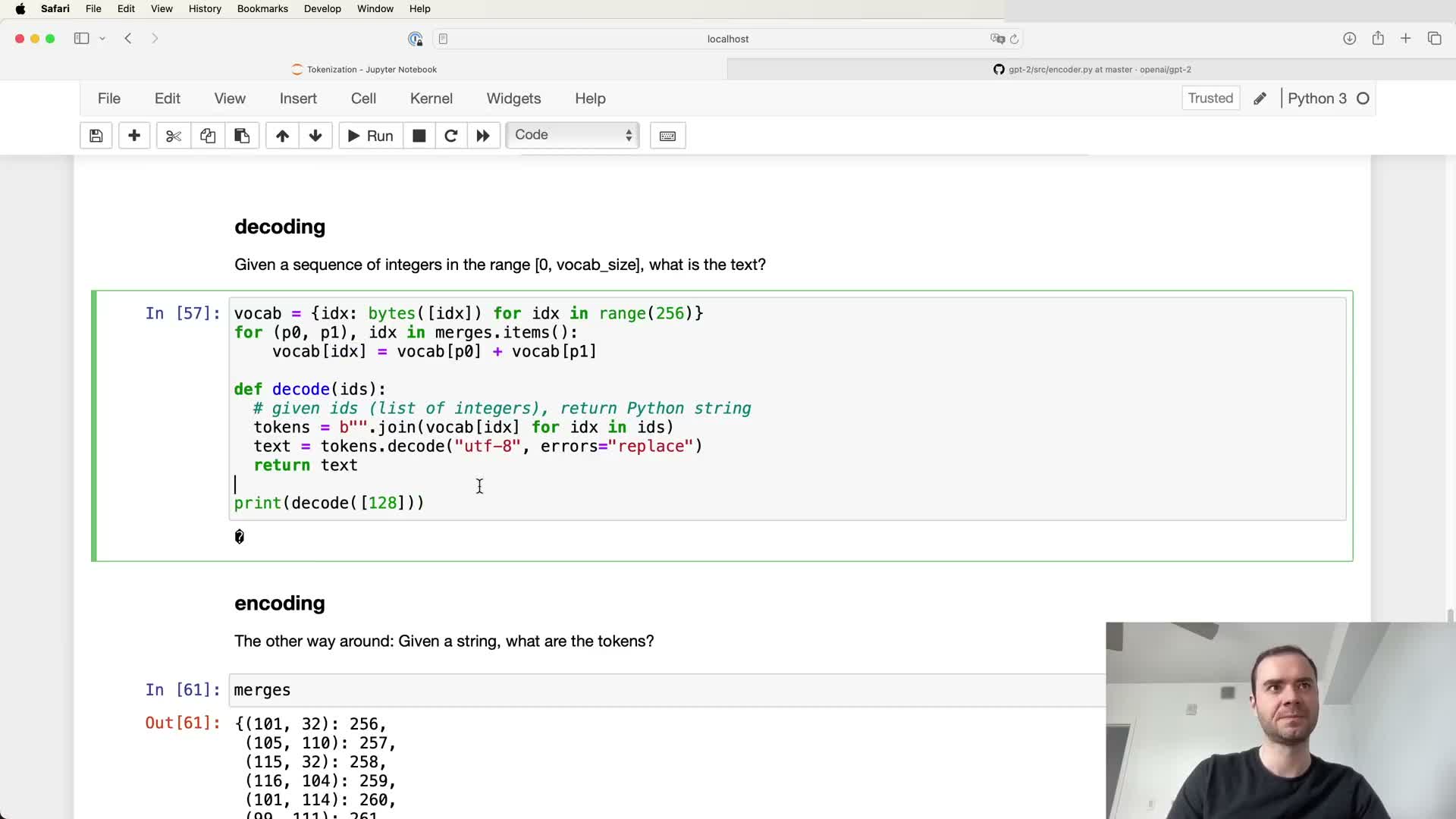

Decoding tokens to text concatenates token byte sequences and decodes via UTF-8 with error handling

Decoding maps each token ID back to its bytes representation, concatenates those bytes, and decodes using UTF-8 to produce a Python string.

- Not every byte sequence is valid UTF-8, so decoders must specify an error policy (e.g., errors=’replace’) to handle invalid sequences robustly.

- Robust decoders therefore maintain the vocab mapping and use UTF-8 decoding with replacement semantics to avoid exceptions and to surface out-of-distribution outputs safely.

Encoding text into tokens applies merges in merge-order and must respect merge eligibility and order constraints

Encoding proceeds by converting text to UTF-8 bytes, mapping bytes to initial token IDs, and then applying permitted merges in the exact order they were created during training.

A practical encoder typically:

- Convert text → UTF-8 bytes → initial token list.

- Compute adjacent-pair candidates on the current token list.

- Look up which candidates appear in the merges table, prioritizing merges with smaller merge indices (earlier merges).

- Replace eligible pairs iteratively until no eligible merges remain or the sequence is fully merged.

Edge cases: handle short inputs, ensure merge lookups return sentinels for ineligible pairs, and preserve merge order to guarantee deterministic encoding.

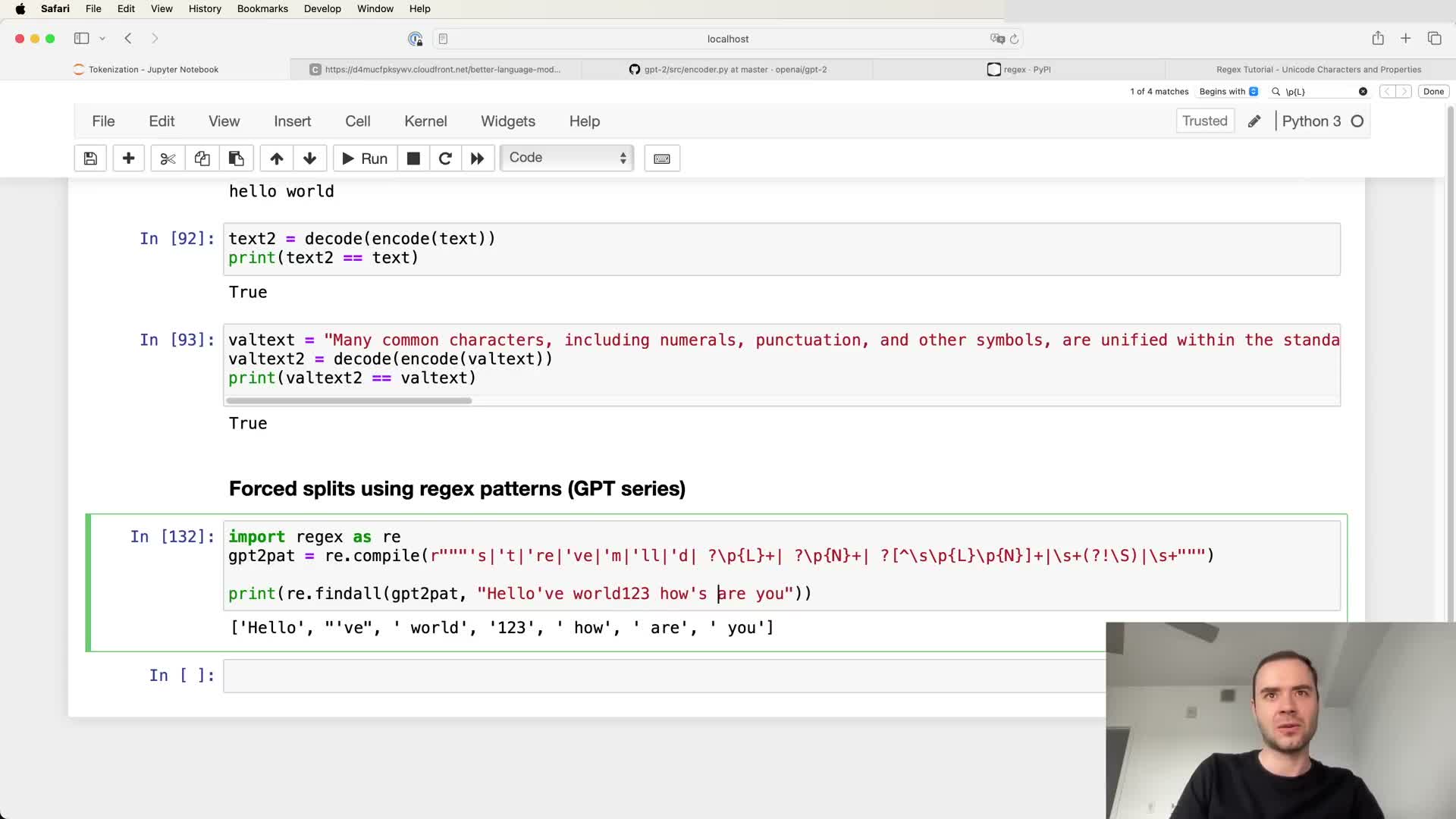

Real-world tokenizers add manual heuristics to BPE: regex chunking prevents semantically bad merges

OpenAI’s GPT-2 tokenizer applies a preprocessing chunking step (a complex regex) that segments text into categories — letters, numbers, punctuation, whitespace — and runs BPE only within those chunks.

- Rationale: prevent undesirable merges such as joining words to punctuation or mixing letters with numbers, which would create many spurious tokens and fragment the vocabulary (e.g., treating ‘dog.’ differently from ‘dog?’).

- These handcrafted chunking heuristics make merges more semantically coherent than blind corpus-level BPE and are important production refinements.

Regex-based chunking contains many subtle language and Unicode issues (apostrophes, case, whitespace handling)

The chunking regex must handle language-agnostic classes while accounting for script-specific details and whitespace behavior.

- It needs to consider accent marks, Unicode apostrophes and glyph variants, case sensitivity, and whitespace grouping.

- Small differences (e.g., ignoring a specific apostrophe glyph or case) change merge eligibility, which affects token frequency and downstream performance.

- The regex often preserves leading spaces as part of tokens (so tokens encode “ space+word” vs “word”) and uses lookahead logic to prioritize common “space+word” combinations.

These heuristics are performant but brittle — they require careful testing across multilingual and code corpora to avoid edge-case failures.

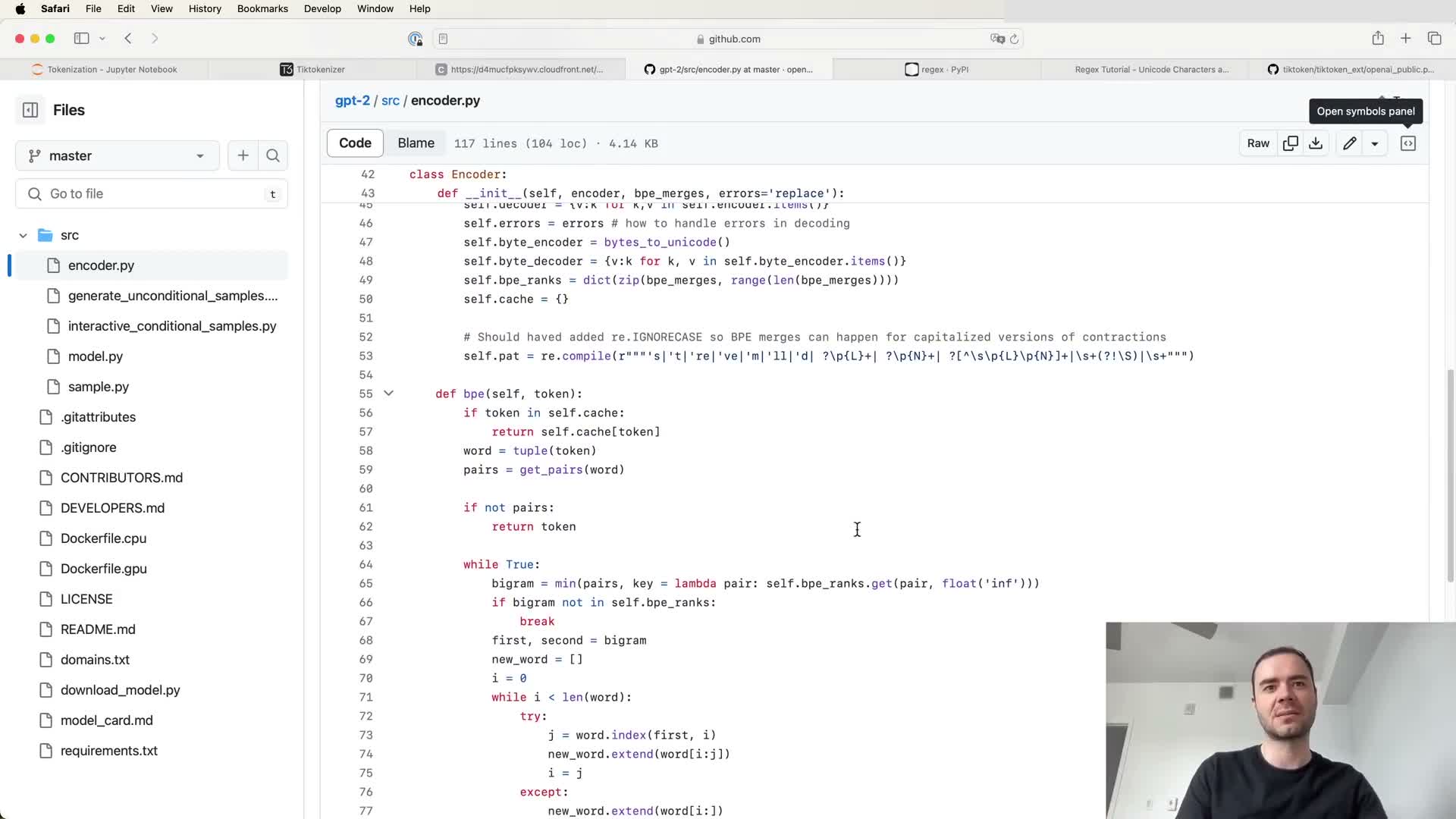

The inference code for GPT-2’s tokenizer (encoder.py) implements BPE application but the original training code was not released

The released GPT-2 encoder artifacts enable deterministic encoding/decoding even though the original merge-training code was not published.

- Two artifacts: encoder.json (maps token IDs to byte sequences) and vocab.bpe (lists the merge operations).

- The released encoder implements the same BPE encode/decode flow: iteratively apply merges according to the merges table and provide encode/decode functions for inference.

Using these two artifacts, one can reproduce GPT-2’s tokenization behavior exactly for encoding, decoding, and debugging purposes.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: