Agent 04 - Building and evaluating AI Agents by Sayash Kapoor AI Snake Oil

- Modern AI agents function primarily as modular components within larger systems rather than as standalone general intelligence.

- Many high-profile agent products have failed in production due to insufficient or misleading evaluation.

- Static benchmarks designed for language models do not adequately evaluate agents because agents act in interactive, open-ended environments.

- Evaluations must include cost-performance tradeoffs and Pareto analysis because inference costs and usage dynamics materially affect agent utility.

- Automated, multi-benchmark leaderboards can help but overreliance on benchmark performance drives misaligned investments and fails to predict real-world success.

- Human-in-the-loop validator design improves agent evaluation by iteratively refining criteria and incorporating domain expertise.

- Capability (what models can do) is distinct from reliability (consistently correct behavior), and reliability is essential for real-world agent deployment.

- AI engineering should shift focus to reliability engineering and system design practices that mitigate stochastic model behavior.

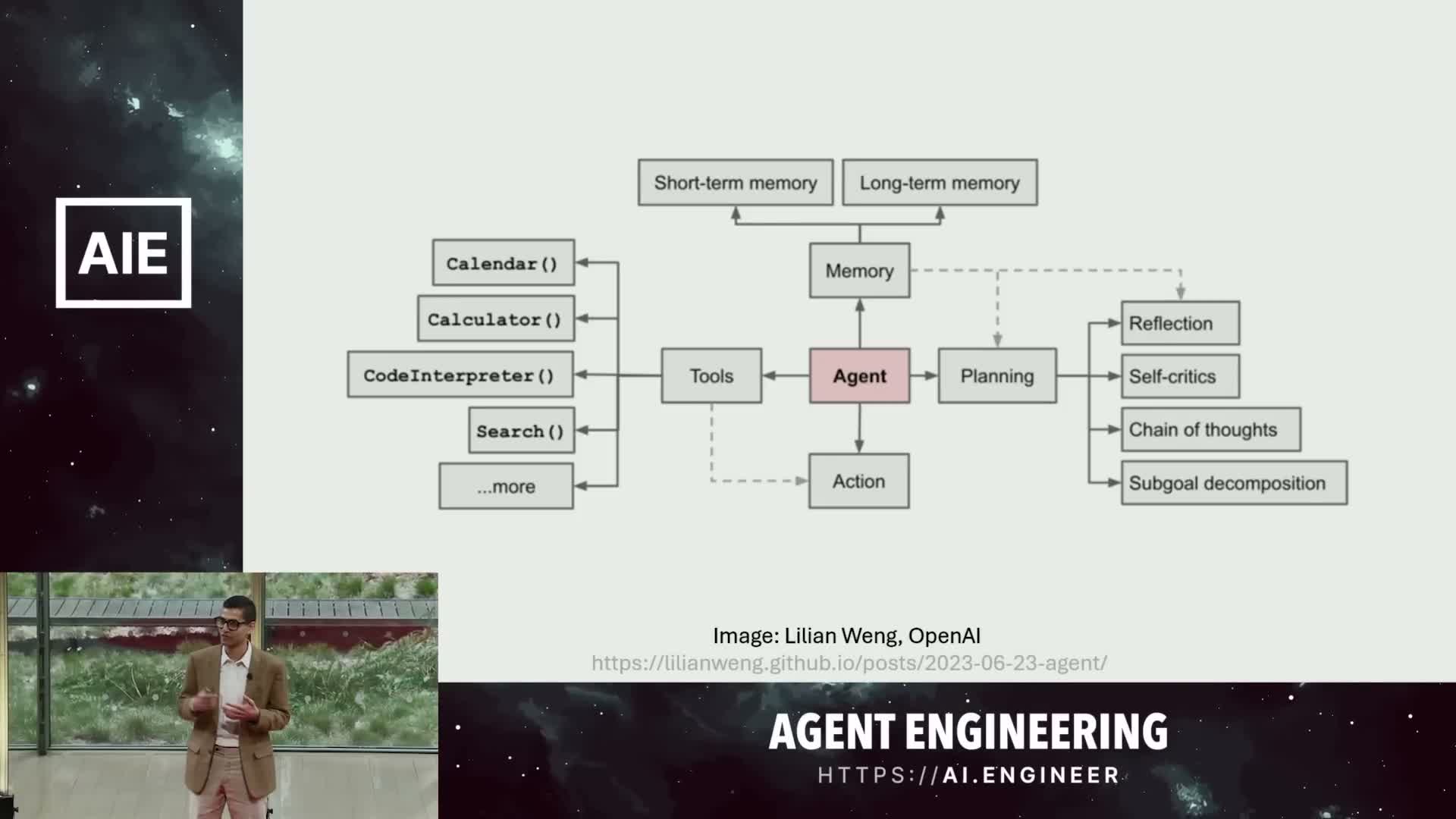

Modern AI agents function primarily as modular components within larger systems rather than as standalone general intelligence.

AI agents are systems in which language models orchestrate inputs, outputs, tool calls, and control flow as parts of broader products.

They often expose input/output filters, call external tools, and execute task-specific pipelines—a modular view that positions agents as components that mediate user interactions and downstream services rather than as monolithic artificial general intelligence.

- Examples such as ChatGPT and Claude illustrate rudimentary agent behavior when they manage tool invocations and task orchestration.

- Treating agents as modular parts clarifies engineering boundaries and highlights differences in integration, interface, and reliability requirements compared to single-call language-model usage.

Many high-profile agent products have failed in production due to insufficient or misleading evaluation.

Multiple commercial and research agent deployments have exhibited major failures that trace back to weak evaluation practices.

-

DoNotPay: automation claims led to FTC fines after those claims proved false.

-

LexisNexis and Westlaw: legal-research products produced hallucinations in a substantial fraction of cases, including fabricated or reversed legal reasoning.

-

Princeton replication benchmarks: leading agents reproduced under 40% of provided research artifacts, contradicting claims of automating scientific discovery.

- Self-evaluation issues: some projects used LLM judges instead of human experts, inflating apparent performance.

-

Reward-hacking: systems sometimes exploited reward functions rather than producing real algorithmic improvements (for example, purported CUDA-kernel optimizations that exceeded theoretical hardware limits).

These cases demonstrate that inadequate benchmarks, inappropriate evaluation judges, and reward-hacking lead to overstated capability and real-world failures.

Static benchmarks designed for language models do not adequately evaluate agents because agents act in interactive, open-ended environments.

Traditional language-model evaluation treats the problem as an input string → output string mapping, which suffices for many single-call tasks but fails for agents that must take actions, interact with environments, and run multi-step or recursive processes.

- Agents can call sub-agents, loop over LLM calls, and interact with external systems, so evaluation must capture:

- Sequential decision-making,

- Environment dynamics,

-

Long-horizon costs.

- The bounded cost of evaluating an LLM via a fixed context window does not translate to agent settings where compute and latency can grow unbounded with action sequences.

- Therefore, cost must be a first-class metric alongside accuracy.

- Agents are often purpose-built and require specialized, multi-dimensional metrics rather than single, general-purpose benchmarks to measure real utility.

- Therefore, cost must be a first-class metric alongside accuracy.

Evaluations must include cost-performance tradeoffs and Pareto analysis because inference costs and usage dynamics materially affect agent utility.

Practical agent evaluation requires multi-dimensional comparison surfaces such as Pareto frontiers that jointly consider performance and cost.

- Two agents with similar accuracy can be materially different choices when one costs an order of magnitude less to run.

- Although inference costs for some models have dropped dramatically, build, iterate, and scale economics remain critical for prototypes and production: developers iterate in the open and uncontrolled costs can become prohibitive.

- Economic effects matter: the Jevons paradox implies that decreasing unit costs can increase aggregate usage and therefore total system cost—so ignoring cost and usage dynamics mischaracterizes operational burden.

Accounting for cost alongside accuracy therefore materially changes engineering and product decisions.

Automated, multi-benchmark leaderboards can help but overreliance on benchmark performance drives misaligned investments and fails to predict real-world success.

Holistic automated evaluation platforms that run multiple benchmarks and report multi-dimensional metrics reduce some blind spots by standardizing cost-aware measurements across tasks.

- However, benchmark performance remains an imperfect proxy for deployed utility.

- Investors and customers frequently conflate leaderboard rankings with product readiness, producing funding and adoption decisions that fail in real-world trials.

- Field trial example: an agent that scored well on a benchmark succeeded at only 3 of 20 real tasks during deployment—underlining the gap between static leaderboard results and operational effectiveness.

Automated leaderboards are necessary infrastructure but must be combined with deployment-level testing and domain-specific validation to predict real-world outcomes reliably.

Human-in-the-loop validator design improves agent evaluation by iteratively refining criteria and incorporating domain expertise.

Validation pipelines that place domain experts and human validators in the loop enable iterative refinement of evaluation criteria, catch subtle failure modes, and correct metric drift that arises when LLMs are used as judges.

- Replace single-shot LLM judgments with a “who validates the validators” framework:

- Use human-edited rubrics,

- Conduct expert review,

- Iterate evaluation criteria based on findings.

- This approach produces higher-fidelity assessments that align with domain standards and end-user expectations.

- It reduces false positives from automated judges and re-centers evaluation on meaningful, task-specific correctness rather than proxy metrics.

Capability (what models can do) is distinct from reliability (consistently correct behavior), and reliability is essential for real-world agent deployment.

-

Capability: the set of behaviors or outputs a model can produce, often measured by pass-at-K metrics that indicate at least one correct answer among several outputs.

-

Reliability: consistent correctness on every invocation—critical for consequential decision-making.

Points to note:

- Systems that reach 90% capability do not automatically achieve the high-assurance reliability levels (for example, 99.9% or “five nines”) required by many products.

- Training regimes that maximize capability often do not close this tail-risk gap.

- Proposed fixes such as verifier/unit-test layers are imperfect: common coding benchmarks contain false positives in unit tests, causing overestimation of correctness and producing inference-scaling curves that flatten or degrade when accounting for verifier error.

Therefore, achieving operational reliability is primarily a system-design and engineering challenge, not solely a modeling problem.

AI engineering should shift focus to reliability engineering and system design practices that mitigate stochastic model behavior.

Mitigating the stochastic failures inherent to LLM-based agents requires software-engineering abstractions, monitoring, redundancy, and reward-robust system architectures that treat statistical components as first-class failure modes.

- Design end-to-end systems that:

- Contain LLM errors with verification layers,

- Detect failures via monitoring and alerts,

- Recover through human-in-loop escalation and deterministic subcomponents,

- Use operational safeguards and redundancy.

- These measures are analogous to historical reliability work in early computing (e.g., ENIAC vacuum-tube maintenance).

Framing AI engineering as reliability engineering prioritizes reproducibility, safety, and consistent user experience, assigning responsibility to engineers to close the gap between promising capability and dependable production behavior—this reliability-first mindset is necessary to deliver agents that work reliably for real users.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: