Agent 05 - How We Build Effective Agents by Barry Zhang Anthropic

- Presentation overview and three guiding principles

- Evolution from single model calls to workflows and agents

- Checklist for when to build agents

- Coding is an ideal agent use case

- Keep agent architecture minimal: environment, tools, system prompt, loop

- Practical optimizations after minimal design

- Think like the agent: context-window constraints and actionable context

- Open research and engineering questions: budgets, self-evolving tools, multi-agent systems

- Three final takeaways and closing contact anecdote

Presentation overview and three guiding principles

The talk introduces three guiding principles for building effective agents:

-

Don’t apply agents to every problem — be selective about where autonomy adds value.

-

Prioritize simplicity during development — keep the initial architecture minimal to iterate quickly.

-

Adopt the agent’s perspective when iterating — design and debug from what the agent actually sees and can do.

This section also defines scope and framing:

- Frames agents as a progression beyond single model calls and predetermined workflows.

- Establishes intent to explore both practical learnings and deeper technical considerations for agent design and deployment.

- Prepares engineering teams to evaluate when autonomous, agentic behavior is appropriate relative to cost, latency, and operational risk.

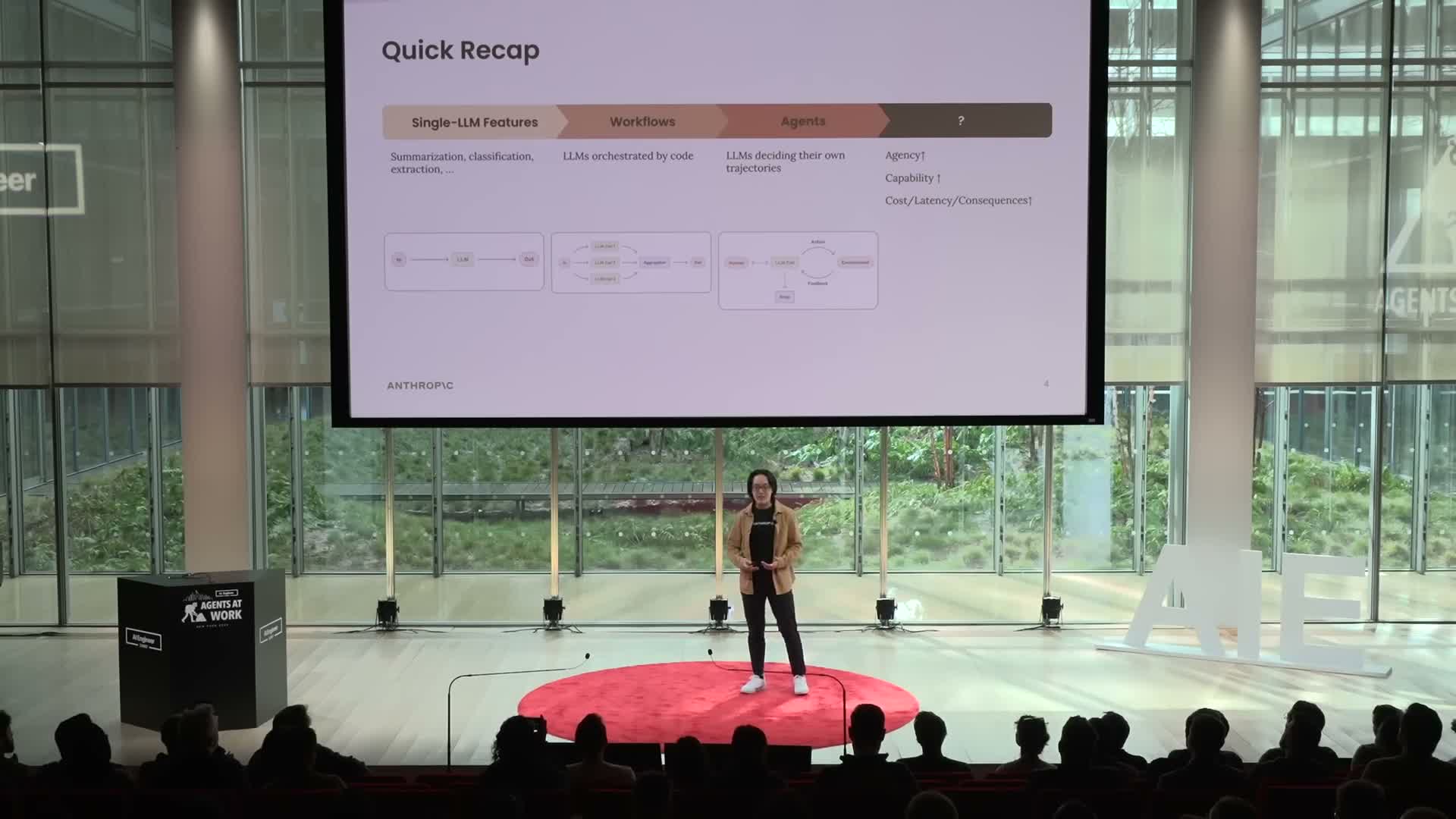

Evolution from single model calls to workflows and agents

Modern application development has moved through three phases:

-

Single API model calls — simple, predictable, low integration surface.

-

Orchestrated workflows — deterministic control flows that trade off cost and latency for predictable performance.

-

Agents — systems that determine their own trajectories based on environmental feedback and introduce autonomy and decision-making.

Key tradeoffs to consider:

-

Increased agency often delivers higher utility and enables complex behaviors.

- It also increases operational cost, latency, and the consequences of errors.

- This motivates careful selection of where to apply agentic systems and reframes engineering tradeoffs versus prior model-integration patterns.

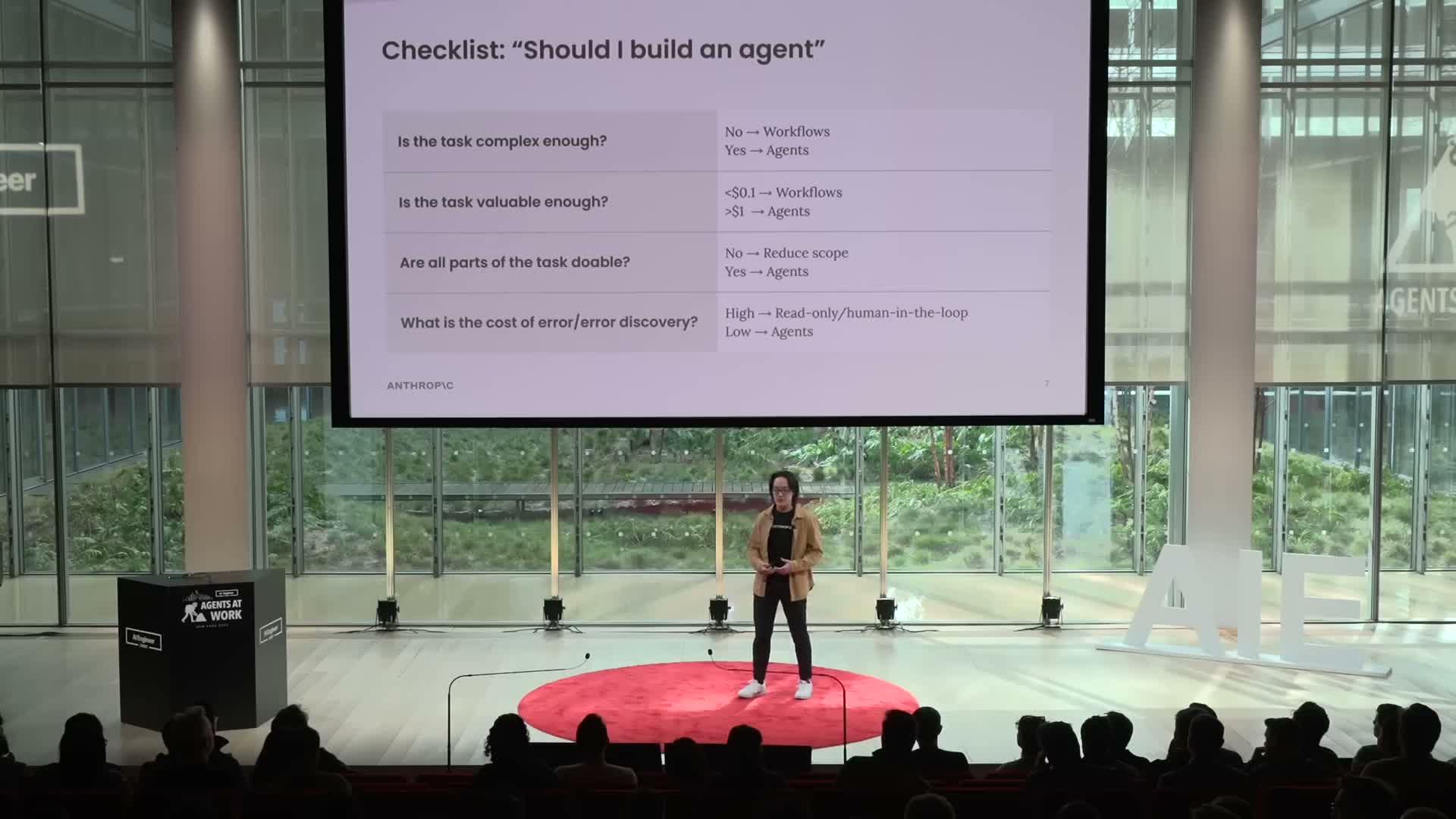

Checklist for when to build agents

Use this practical checklist to decide whether to use an agent:

- Task complexity and ambiguity:

- Is the decision space ambiguous or too large to exhaustively enumerate?

- Is the decision space ambiguous or too large to exhaustively enumerate?

- Economic value and budget:

- Is there sufficient per-task budget to cover token and inference costs?

- Is there sufficient per-task budget to cover token and inference costs?

- Critical capability risks:

- Can the agent’s critical capabilities be derisked to avoid fatal bottlenecks?

- Can the agent’s critical capabilities be derisked to avoid fatal bottlenecks?

- Error detectability and cost:

- How detectable and costly are errors and delayed error discovery?

- How detectable and costly are errors and delayed error discovery?

Recommended constraints when risk is high:

- Limit autonomy (for example, read-only access or human-in-the-loop) to retain trust while scaling.

- When bottlenecks exist, prefer scope reduction and simplification to control latency and runaway costs.

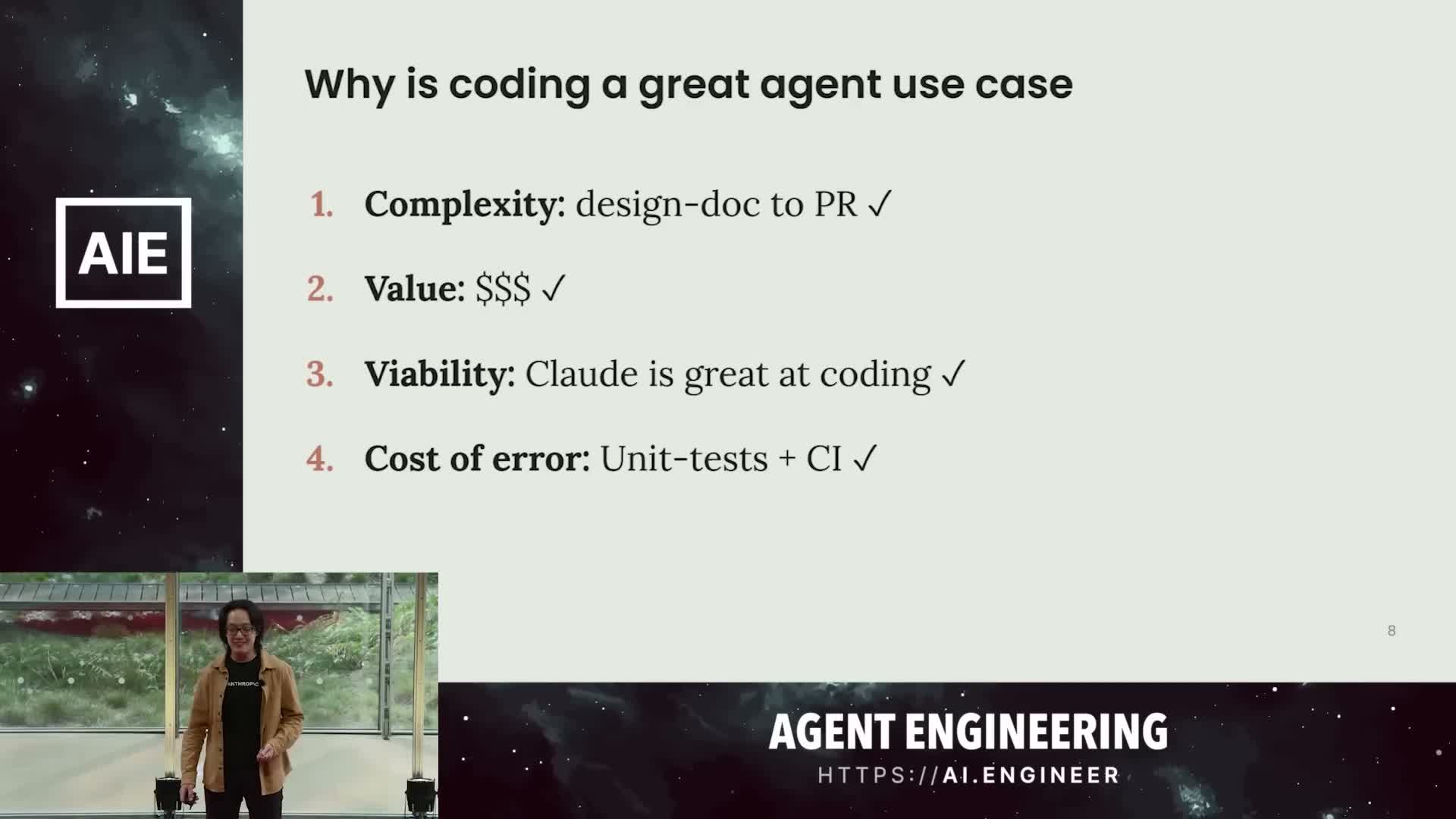

Coding is an ideal agent use case

Why coding tasks are a strong fit for agents:

- They combine ambiguity, measurable value, and verifiability.

- Translating a design doc into a pull request is a complex, open-ended workflow where automation provides outsized benefit.

- Many parts of the coding pipeline are tractable via tool integration (edit, test, CI).

- Outputs are verifiable through unit tests and continuous integration, creating objective feedback loops for evaluation.

- These properties reduce the risk of silent failures and make iterative improvement feasible.

Conclusion: coding is both a practical and economically justifiable domain for deploying autonomous agents, explaining the strong product-market fit for coding agents in production.

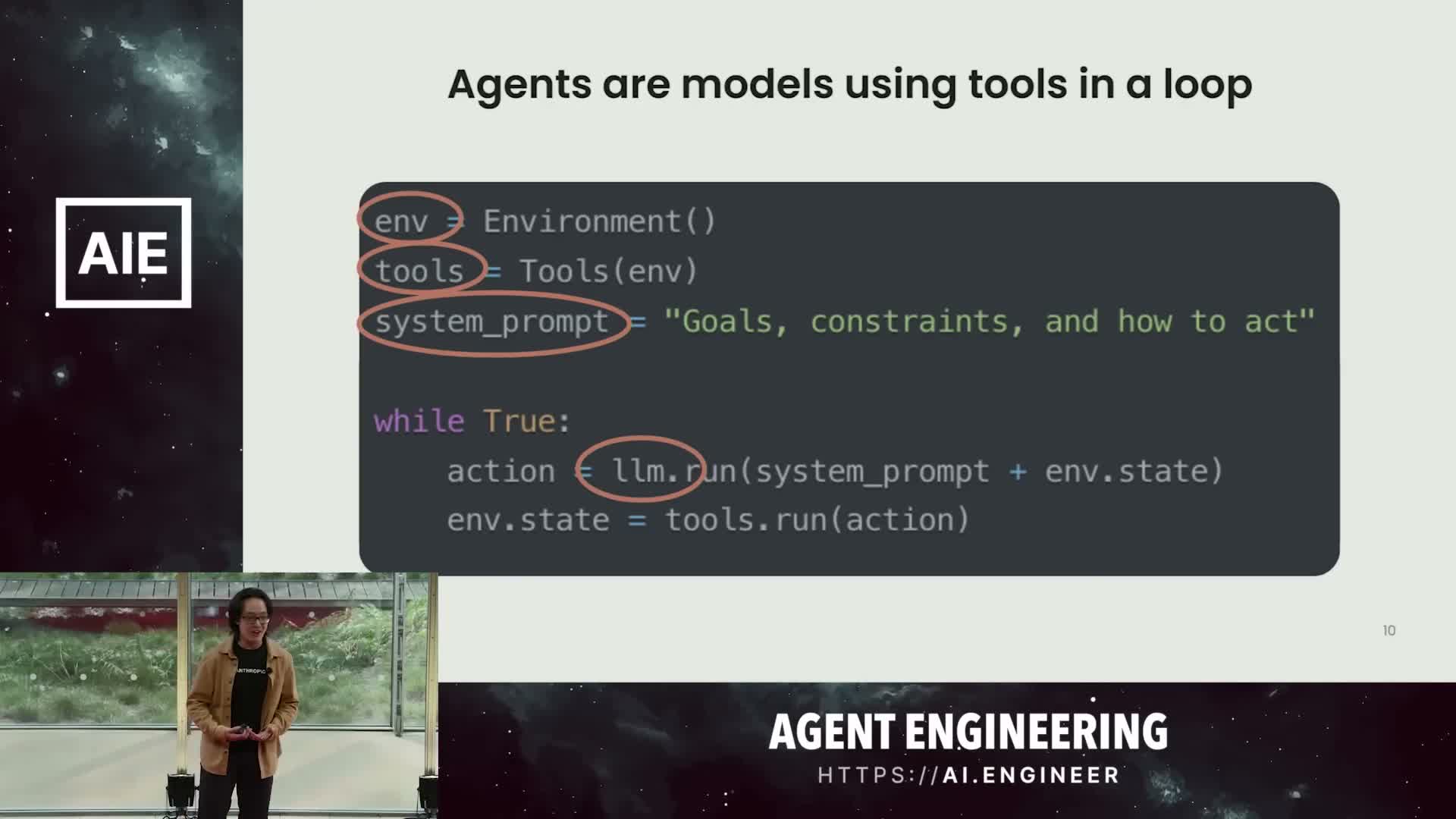

Keep agent architecture minimal: environment, tools, system prompt, loop

An effective, minimal agent architecture contains three core components:

-

Environment — the external context and state the agent operates in.

-

Tools — action and feedback interfaces the agent can call (editors, test runners, APIs).

-

System prompt — encodes goals, constraints, and desired behavior for the model.

These are executed in a recurring model decision loop:

- Observe formatted context and tool feedback.

- Decide on an action (or tool call) according to the system prompt.

- Execute the action via the environment or tools and ingest the result.

- Repeat.

Design guidance:

- Keep these elements simple to accelerate iteration — most early wins come from refining environment integration, tool selection, and prompt design rather than adding structural complexity.

- The model-loop abstraction generalizes across use cases: different products can share the same codebase while varying only environment bindings, toolsets, and system prompts.

- This modular minimalism enables rapid experimentation and focused later optimizations once behaviors stabilize.

Practical optimizations after minimal design

After validating behavior with the minimal backbone, apply targeted optimizations to reduce cost and latency and improve trust:

Techniques to consider:

-

Cache or catch the agent’s trajectory to avoid re-searching expensive decision paths.

-

Parallelize independent tool calls to lower wall-clock latency.

-

Instrument progress presentation so users can verify and trust agent actions (transparent status, checkpoints).

Recommended development sequence:

- Validate core behavior with simple environment, tools, and prompt.

- Measure operational costs, latency, and failure modes.

- Iteratively add optimizations (caching, parallelization, UX instrumentation) only when they serve measurable operational goals.

This balances rapid product iteration with long-term performance and reliability improvements.

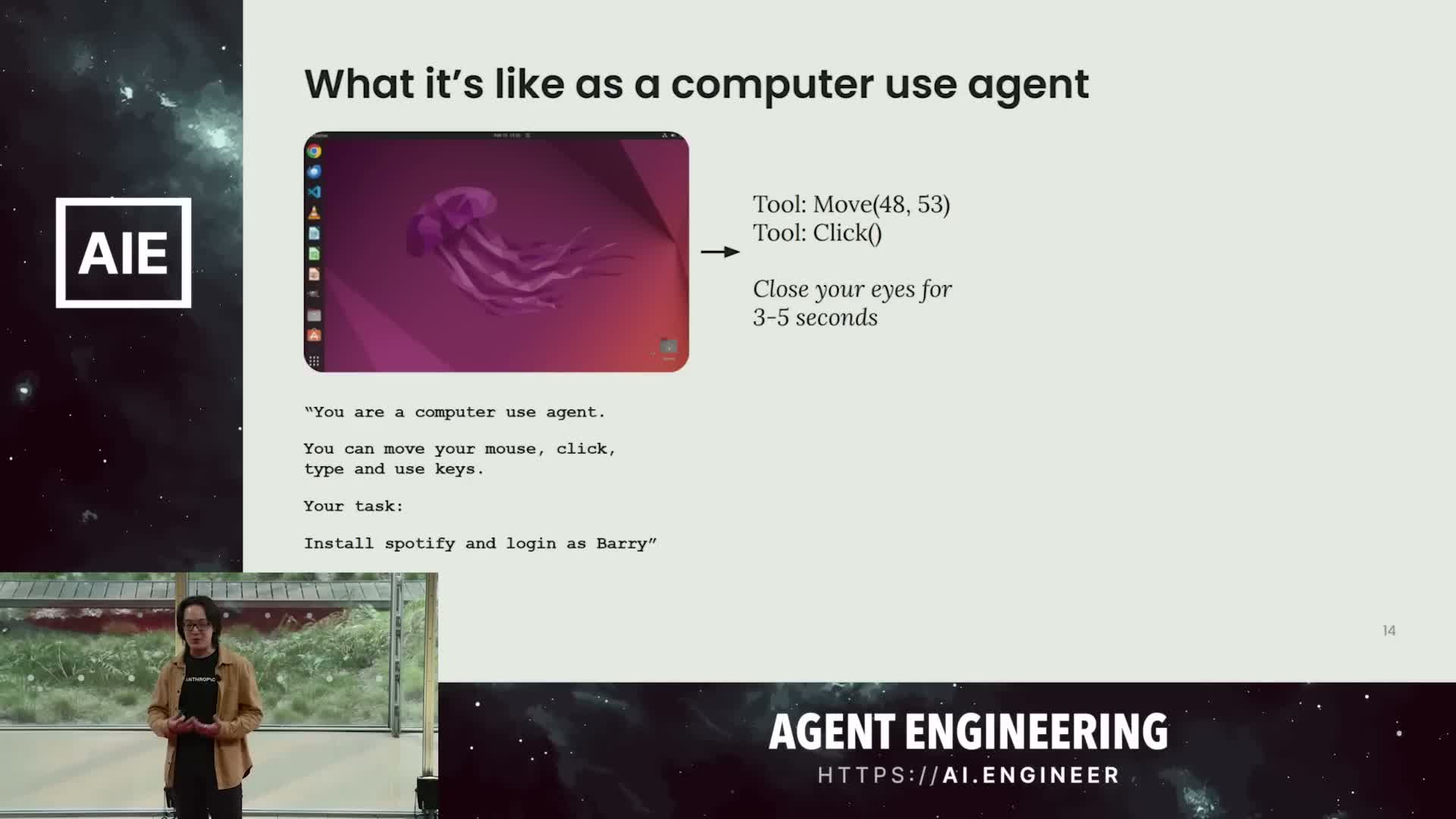

Think like the agent: context-window constraints and actionable context

Agents are limited by context-window constraints and only perceive the world through formatted context and tool feedback:

- Typical inference visibility is within a 10–20k token window, so design and debugging must model the agent’s actual information state.

- For interactive agents (e.g., UI agents) the agent is effectively blind during tool calls and only observes discrete snapshots and textual descriptions.

- Therefore supply critical metadata (screen resolution, element coordinates, recommended actions, explicit limitations) to avoid brittle behavior.

Practical steps for engineers:

-

Simulate full end-to-end tasks from the agent’s perspective to find missing context and guardrails.

- Use models to introspect agent trajectories by asking the model to explain past decisions and request additional parameters.

- Treat the agent’s view as the primary source of truth for prompt engineering, tool design, and reliability work.

Open research and engineering questions: budgets, self-evolving tools, multi-agent systems

Key open problems for agent engineering include:

-

Budget and latency constraints:

- Need mechanisms to express and enforce time, token, or monetary budgets so deployments are economically viable.

- Need mechanisms to express and enforce time, token, or monetary budgets so deployments are economically viable.

-

Agents evolving their own tools (self-evolving tools):

- Meta-tools that let agents iteratively refine tool ergonomics and parameterization would extend generality but raise safety and governance questions.

- Meta-tools that let agents iteratively refine tool ergonomics and parameterization would extend generality but raise safety and governance questions.

-

Robust multi-agent collaboration protocols:

- Requires communication models beyond synchronous user-assistant exchanges, including asynchronous messaging, role definition, and recognition to enable parallelized subagents and separation of concerns.

- Requires communication models beyond synchronous user-assistant exchanges, including asynchronous messaging, role definition, and recognition to enable parallelized subagents and separation of concerns.

Addressing these areas will expand production use cases and clarify architectural patterns for large-scale agent deployments.

Three final takeaways and closing contact anecdote

The three closing takeaways:

-

Don’t build agents for every task — be selective and justify agentic complexity.

-

Prioritize simplicity during early iteration — validate with a minimal environment-tools-prompt loop.

-

Adopt the agent’s perspective — provide the right context and guardrails for reliable decision-making.

Closing guidance for engineering teams:

- Validate use cases before investing heavily.

- Implement a minimal environment-tools-prompt loop and iterate with agent-centric tests and tooling.

- Apply optimizations only when they meet measurable operational goals (cost, latency, trust).

The session closes with an invitation to collaborate on open questions about budgets, tool evolution, and multi-agent interaction, plus a brief personal anecdote underscoring a practical orientation toward building useful AI systems — and encouragement to continue building and exchanging ideas.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: