MIT 6.S184 - Lecture 5 - Diffusion for Robotics

- Challenges of applying diffusion and flow models to robotics differ from image generation

- Diffusion models for robotics condition on robot observations and denoise future trajectory waypoints

- Receding-horizon diffusion planning produces coherent short-horizon trajectories

- Teleoperation and diverse human demonstrations are the primary data sources for robot behavior learning

- Robot morphology and camera configuration critically affect learned policy robustness

- Generalist models use language or goal conditioning to scale beyond single behaviors and inference is executed asynchronously with a low-level safety controller

- Architectural upgrades improve performance: shared encoders, transformers, and diffusion heads

- Single-behavior training produces many concrete manipulation capabilities but faces memory and horizon limitations

- Action representation as commanded end-effector pose with impedance control makes policies force-aware

- Closed-loop wiping example demonstrates robust recovery and the practical utility of behavior cloning

- Simulation and tactile sensing augment real-world training and evaluation pipelines

- Out-of-distribution shifts produce brittleness with characteristic failure modes

- Data curation practices—short memory, multimodality, pauses, observability, and intentional imperfection—are crucial for robustness

- Scaling to multitask generalist models leverages diverse datasets and pretrained visual-language models

- Generalist versus specialist tradeoffs and emergent cooperative behaviors

- Denoising dynamics are implementation-specific and are decoupled from predicted action trajectories using alternative training objectives

- Long-term research goal: build general-purpose, scientifically-understood robotic systems and scale research teams and collaborations

Challenges of applying diffusion and flow models to robotics differ from image generation

Applying diffusion and flow models to robotics introduces distinct practical constraints compared to image generation because robotics involves much smaller datasets and closed-loop performance requirements.

Robotic models must run in a physical feedback loop, which places strict latency and reliability requirements on inference and makes distribution shift during deployment a central concern.

The combination of limited data and the need for robust closed-loop behavior changes many design decisions, including:

- Model size and capacity trade-offs

- Conditioning modalities (what sensors and signals the model consumes)

-

Evaluation strategies that emphasize real-time safety and robustness

Effective deployment therefore requires adapting generative modeling techniques to real-time control constraints and the realities of physical interaction.

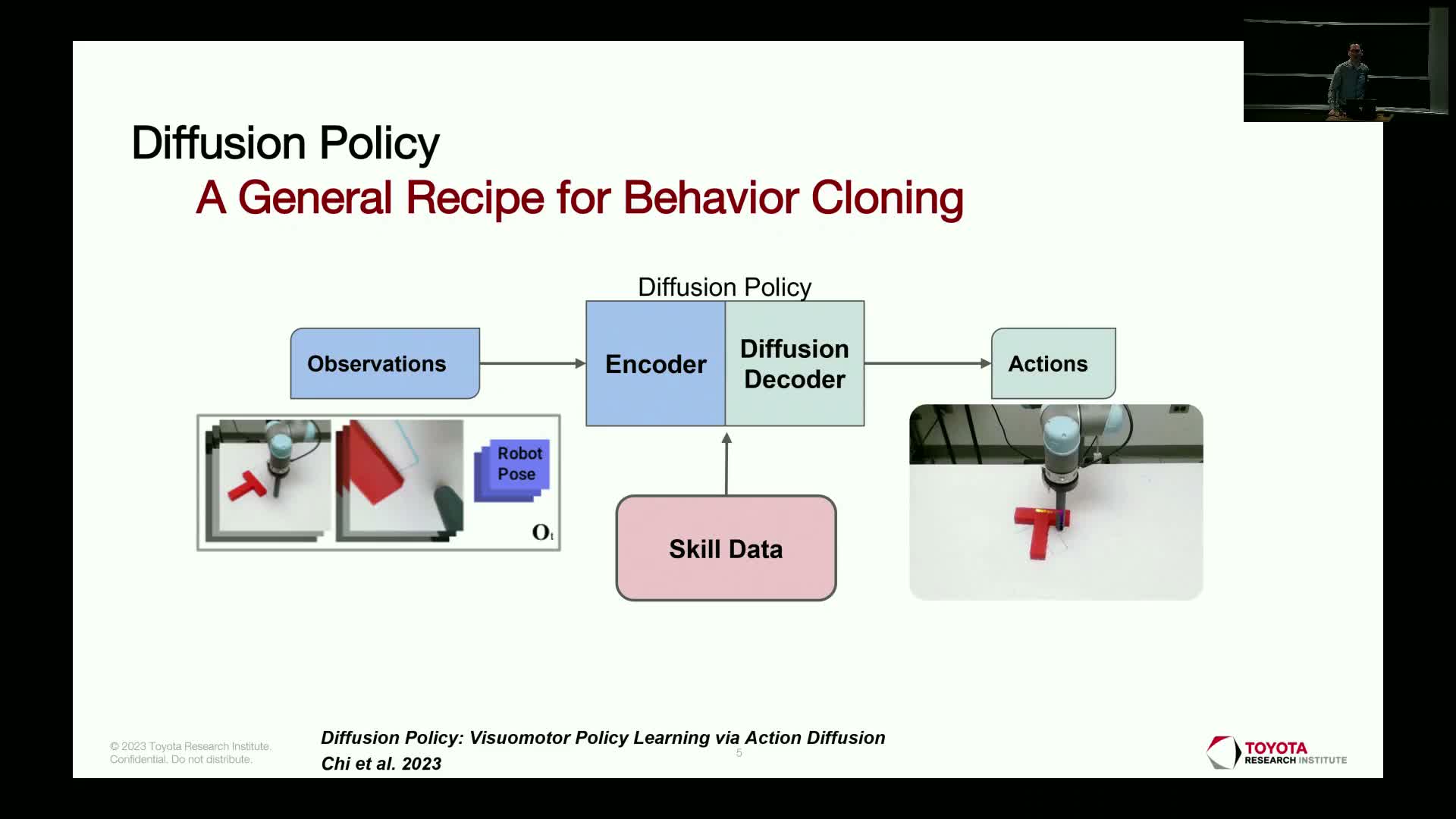

Diffusion models for robotics condition on robot observations and denoise future trajectory waypoints

Diffusion-based robotic policies treat the prediction problem analogously to image diffusion, but the target is a temporally ordered sequence of control waypoints rather than pixels.

Key aspects:

- The model conditions on robot observations (camera images, proprioception such as pose and joint states).

- It denoises a noisy sequence of future waypoints to produce a coherent short-horizon plan—typically predicting at rates like 10 Hz for windows around two seconds.

Inference is performed online in a receding-horizon loop:

- Predict a short window of waypoints (the plan).

- Execute a subset of actions from that window while inference runs again.

- Refresh the plan to remain reactive to new observations.

This formulation emphasizes low-latency inference (ideally under one second) and dense waypoint prediction rather than long open-loop rollouts.

Receding-horizon diffusion planning produces coherent short-horizon trajectories

Visualizing diffusion outputs in simple 2D tasks clarifies the approach:

- The noising process starts with random waypoint trajectories. Denoising produces smooth, task-specific trajectories that reach the goal.

- By predicting a dense sequence of future poses and repeatedly re-planning, the system achieves closed-loop behavior that can recover from intermediate perturbations and unexpected environment changes.

- The receding-horizon nature ensures plans are short enough to be reactive yet long enough to encode meaningful motion structure, enabling complex manipulations with relatively simple conditioning and modest data.

Practical success also requires engineering tips and tricks around data curation, sensor placement and inference scheduling to maximize robustness.

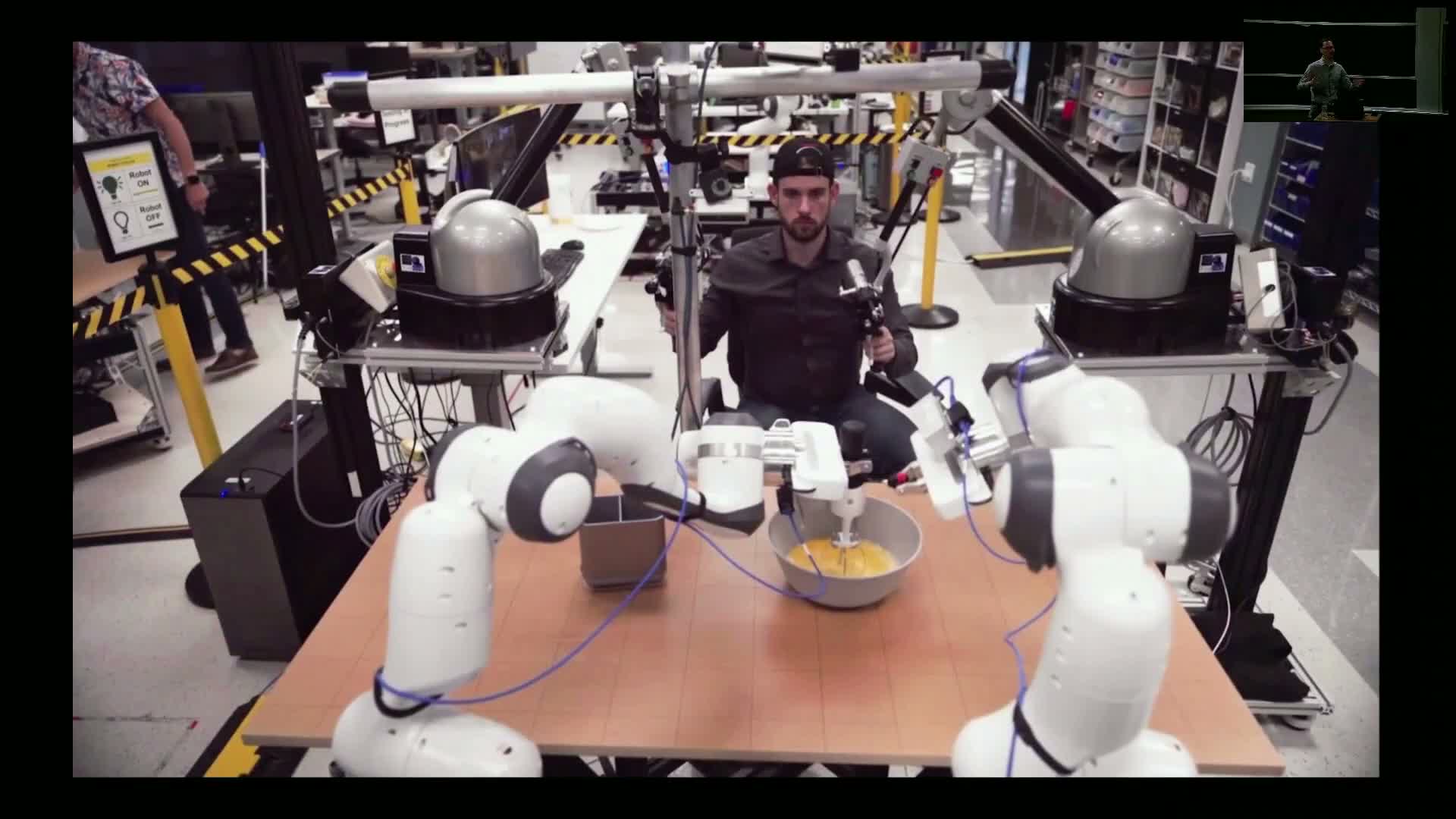

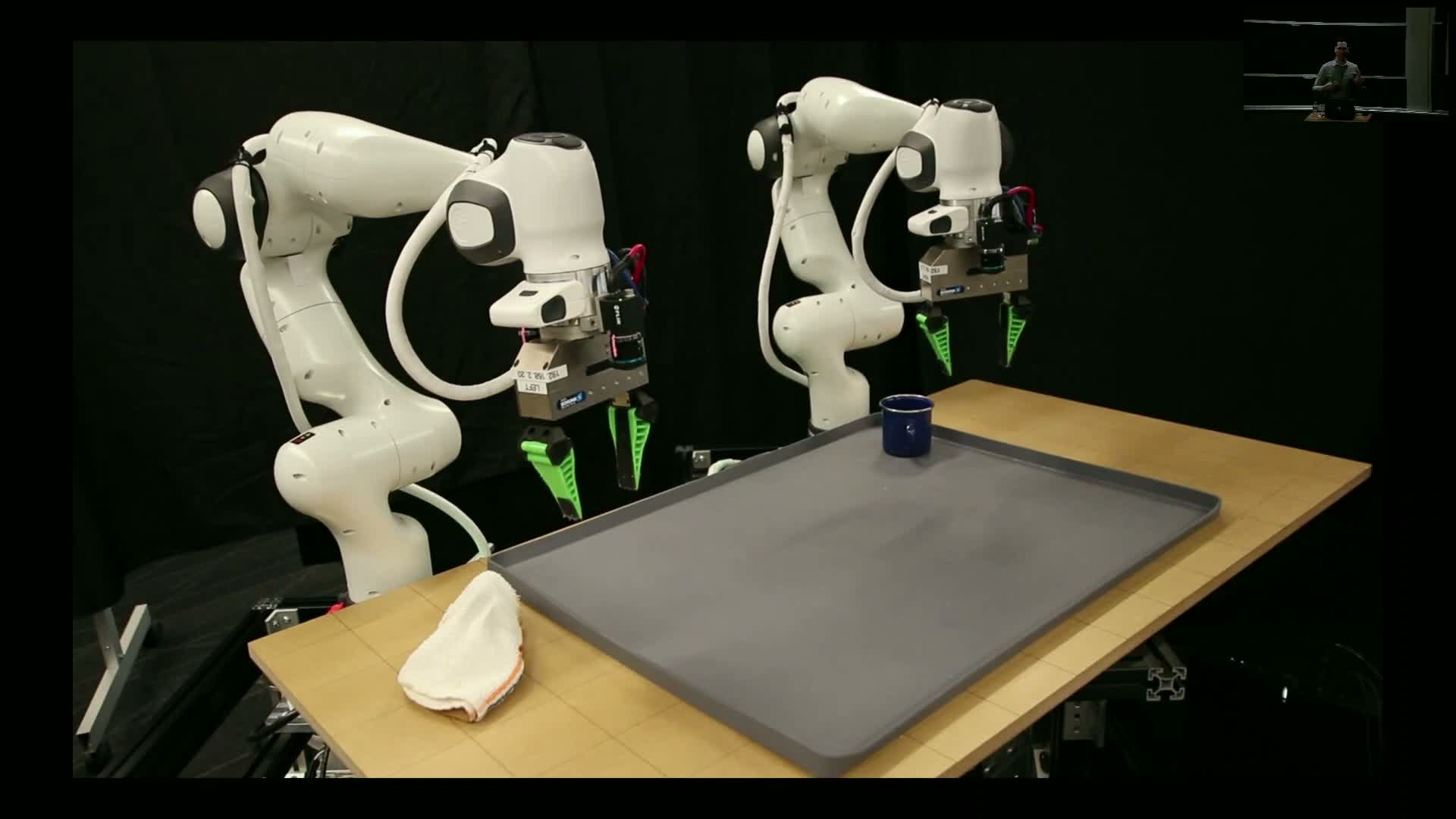

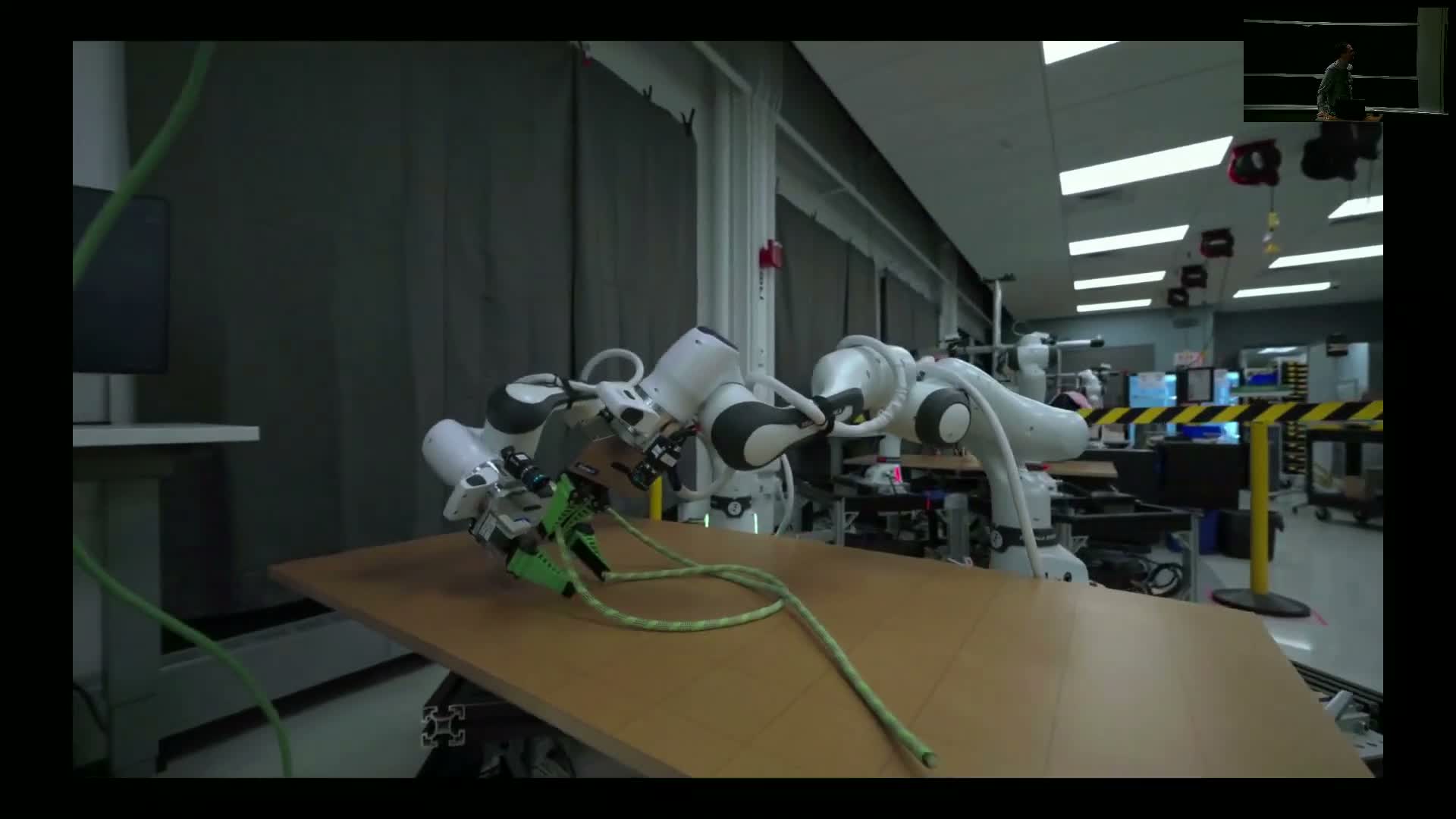

Teleoperation and diverse human demonstrations are the primary data sources for robot behavior learning

Supervised learning of behavior-diffusion policies uses human demonstrations as the core dataset, typically collected via teleoperation interfaces:

- High-bandwidth haptic devices

-

VR teaching rigs

- Six-degree-of-freedom mice

- Handheld instrumented grippers

Typical data-collection patterns:

- A single behavior: a few hundred demonstrations collected over a few hours of teleoperation.

- Yields tens of thousands of time-indexed samples at 10 Hz for training.

- Different collection modalities are combined into a unified dataset for single-behavior training.

Careful teleop design (including haptic feedback) improves demonstration quality. This data-centric approach emphasizes instrumented, repeatable teaching workflows as the primary lever for performance improvements in single-task settings.

Robot morphology and camera configuration critically affect learned policy robustness

Physical station design (camera count, viewpoints, wrist-mounted cameras) strongly influences policy generalization because policies easily overfit to static camera configurations when data is limited.

Practical recommendations:

- Add wrist cameras that move with the gripper to provide natural image randomization and shared visual features.

-

Share the same image encoder across wrist and scene cameras to enable cross-view feature transfer.

- Design hardware and sensor placement to increase visual diversity in training data, reducing sensitivity to small shifts in camera position or scene appearance.

In short, hardware design and sensor placement are as important as model architecture for robust deployment.

Generalist models use language or goal conditioning to scale beyond single behaviors and inference is executed asynchronously with a low-level safety controller

Scaling from one behavior to many typically uses conditioning modalities such as language prompts or goal images to specify the desired behavior for a generalist model.

Execution architecture on real robots:

- A buffer of low-level commands is maintained and executed by a high-frequency controller (impedance or position controller) that enforces safety constraints.

- The diffusion policy runs asynchronously to refill the buffer and replan.

Typical practice:

- Predict a horizon of actions (e.g., 16–32 steps).

- Execute a portion of them.

- Re-invoke inference and overwrite the buffer, enabling graceful handling of variable compute latency and continuous reactivity.

This combines high-level learned planning with classical control primitives to ensure safety and smooth execution.

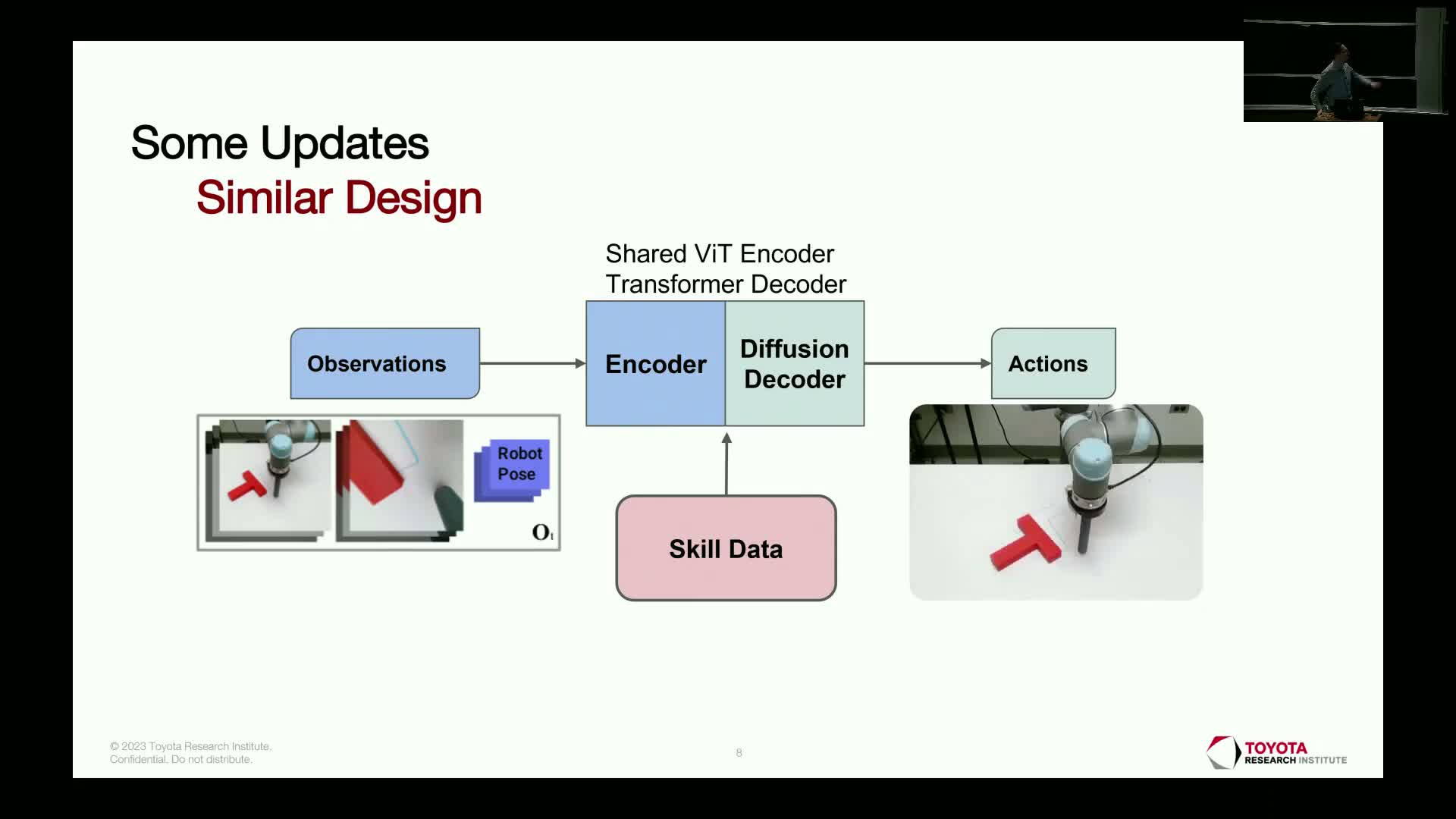

Architectural upgrades improve performance: shared encoders, transformers, and diffusion heads

Early diffusion policy work has evolved to incorporate modern ML practices:

-

Shared visual encoders across multiple cameras (instead of independent encoders).

-

Transformer-based backbones for richer spatiotemporal modeling.

-

Attention-based conditioning between observations and action tokens.

Benefits:

- Increased cross-view feature sharing and improved sample efficiency on small robotics datasets.

- In some cases, a Transformer head resembles a diffusion transformer that models the denoising process in action-space.

These upgrades keep the core diffusion objective but substantially boost empirical performance and form a practical baseline for training new robotic behaviors from scratch.

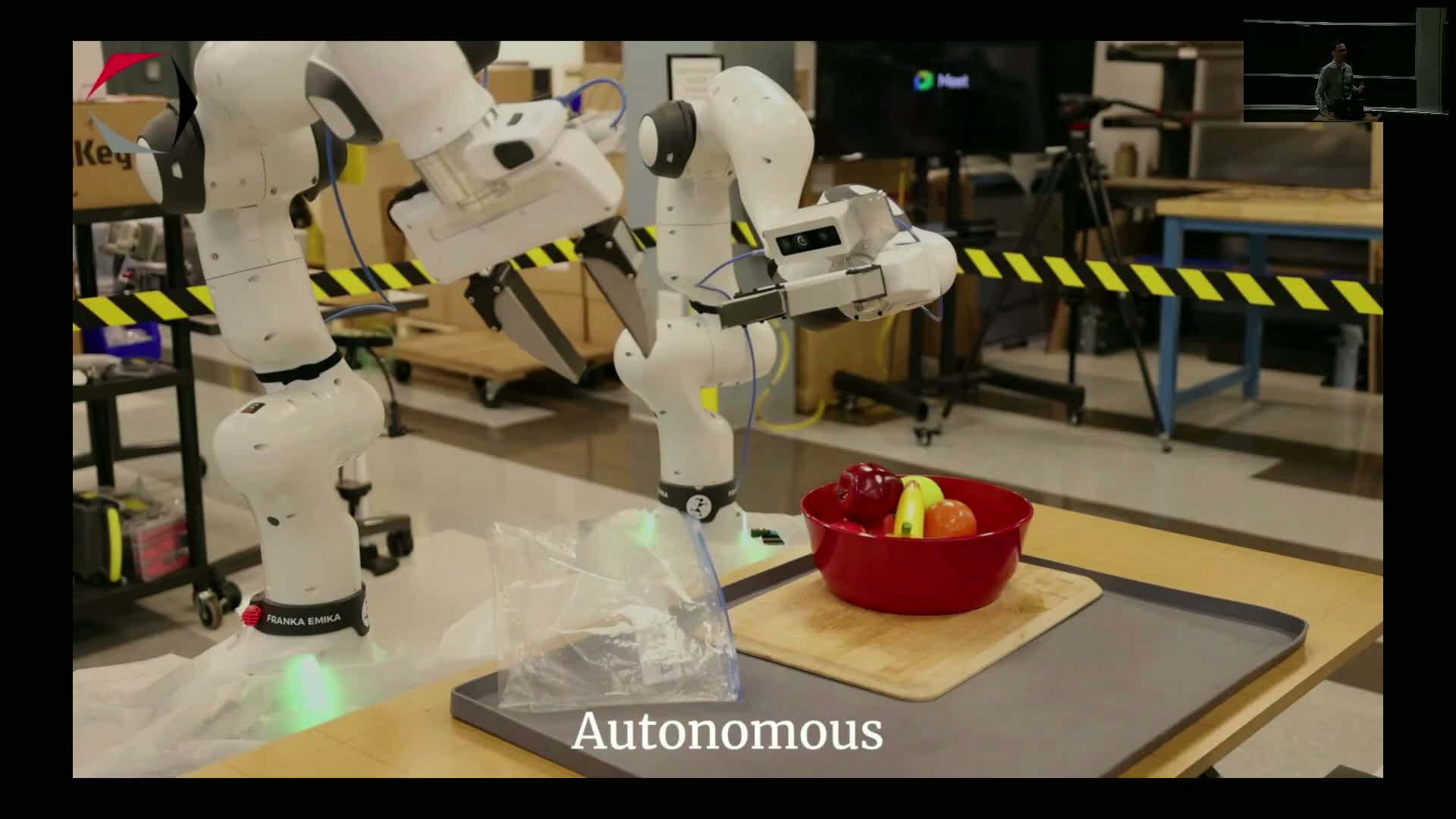

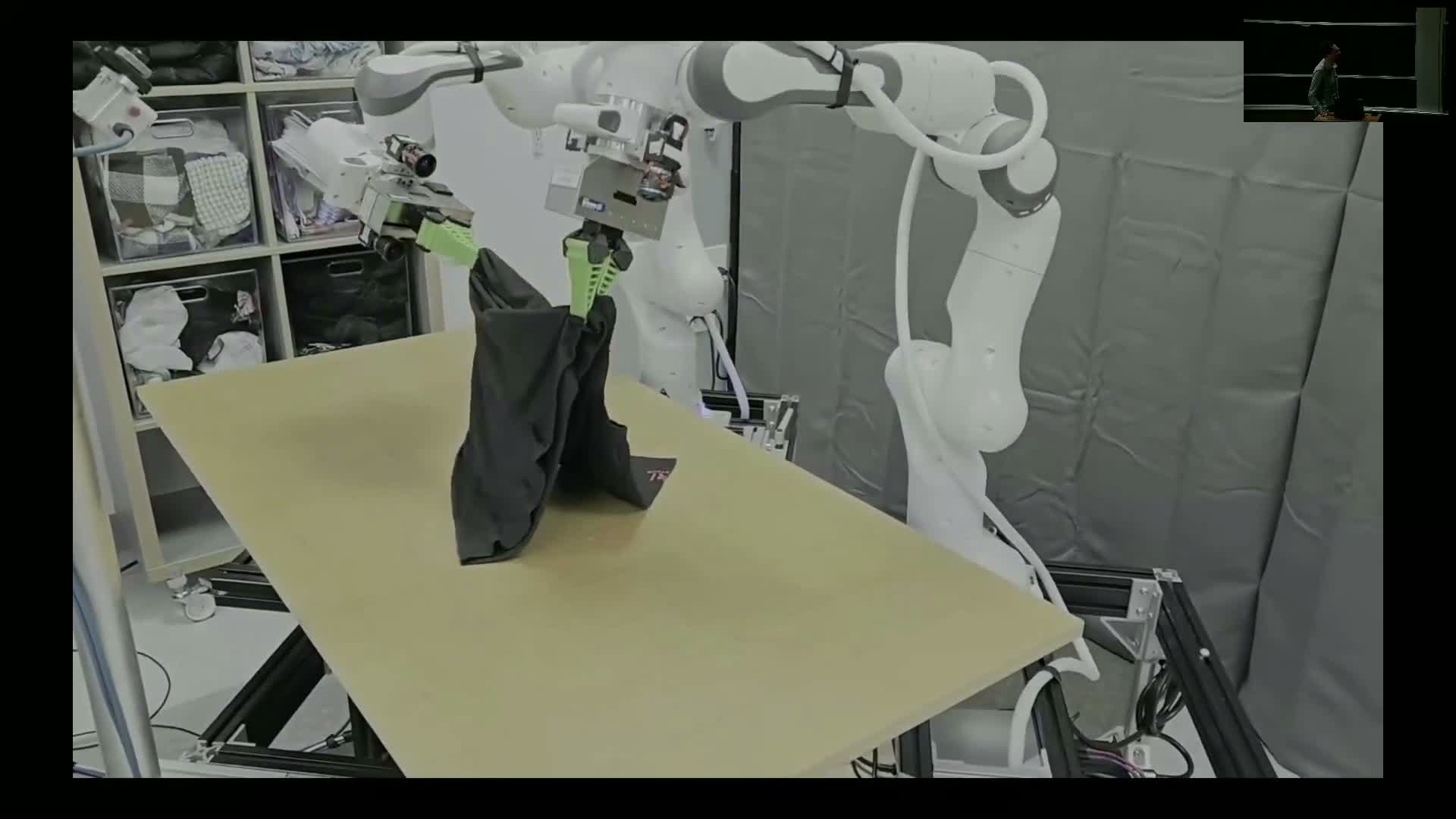

Single-behavior training produces many concrete manipulation capabilities but faces memory and horizon limitations

Training one behavior at a time with the diffusion recipe yields a wide variety of capabilities—cloth folding, wiping, deformable-object handling and extended multi-step skills—often from a few hundred demonstrations.

Observed limitations and patterns:

- Learned policies typically have limited implicit memory (on the order of about one second of history).

- Policies become brittle when asked to remember or reason across much longer horizons; this is more a data limitation than an architectural one in the from-scratch regime.

-

Long behaviors are often realized as implicit mode-switching between many short sub-behaviors rather than explicit long-term memory.

Practical workflow: iterative prototyping, adding demonstrations and careful curriculum design often convert short successful snippets into richer, longer-running skills.

Action representation as commanded end-effector pose with impedance control makes policies force-aware

The most common action representation combines commanded end-effector poses (six-DOF targets) with an underlying impedance-control mode that maps position commands to commanded forces.

Why this works:

-

Impedance control treats a position setpoint as a target converted to forces by controller gains, so contact implicitly controls applied force magnitude.

- Providing a short history of previous commands and visual feedback enables the policy to implicitly infer contact forces from visual-proprioceptive deltas, enabling force-aware manipulation without explicit force sensing.

This representation decouples high-level learned planning from low-level safety and torque-limiting control, while enabling compliant interactions.

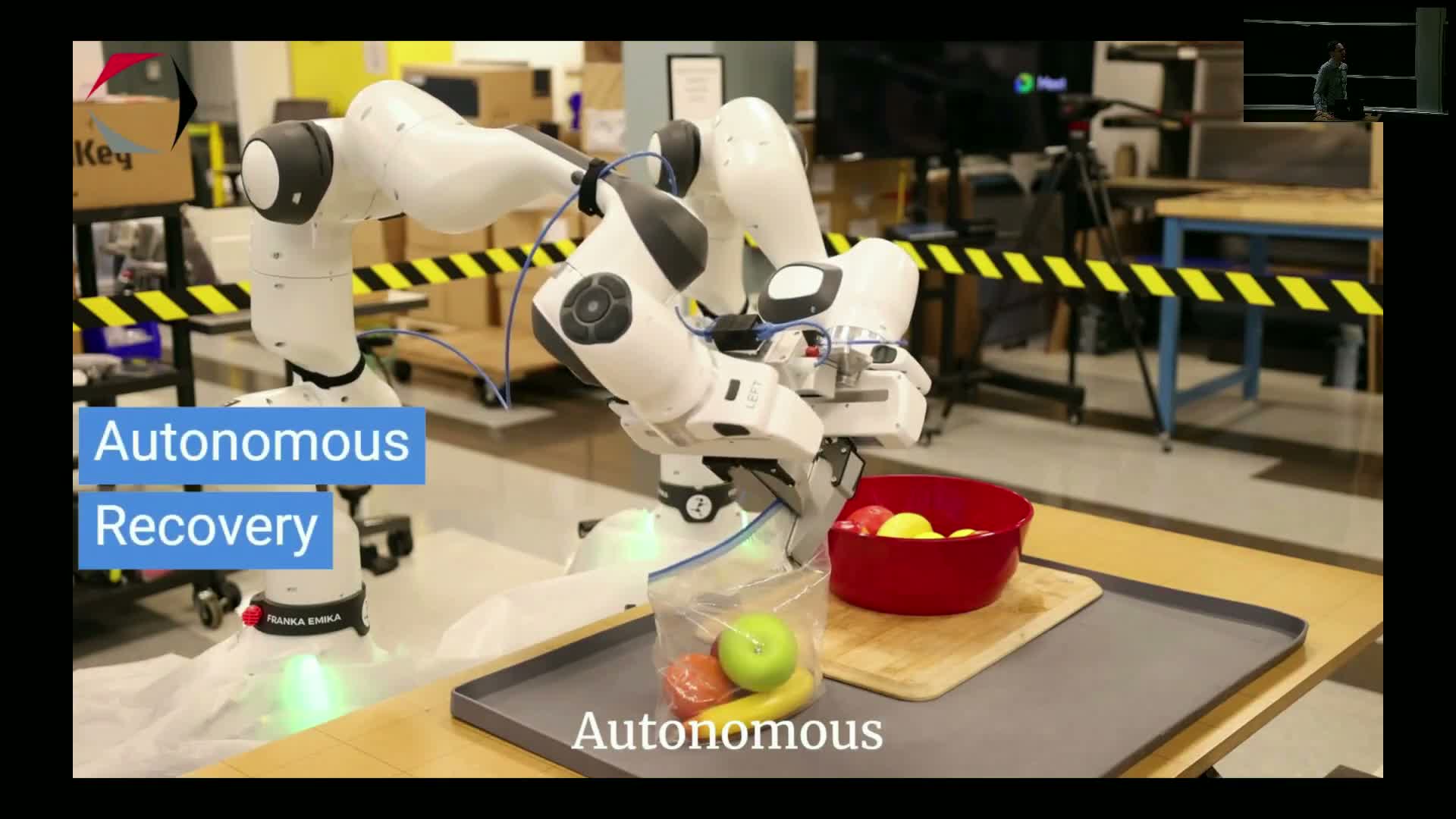

Closed-loop wiping example demonstrates robust recovery and the practical utility of behavior cloning

Closed-loop learned wiping policies repeatedly adjust actions until the visual evidence of dirt is removed, demonstrating an emergent recovery behavior that is robust in the trained environment.

Empirical lessons:

- Although behavior cloning was criticized for replaying demonstrations, careful data curation and scaling of supervised regimes produce substantial generalization and reactive capability.

- Simple supervised recipes, receding-horizon diffusion planning, and good teleoperation data produce surprisingly capable closed-loop manipulators for many everyday tasks.

Key caveat: these behaviors are primarily reliable within the training lab distribution unless explicitly hardened via data variation.

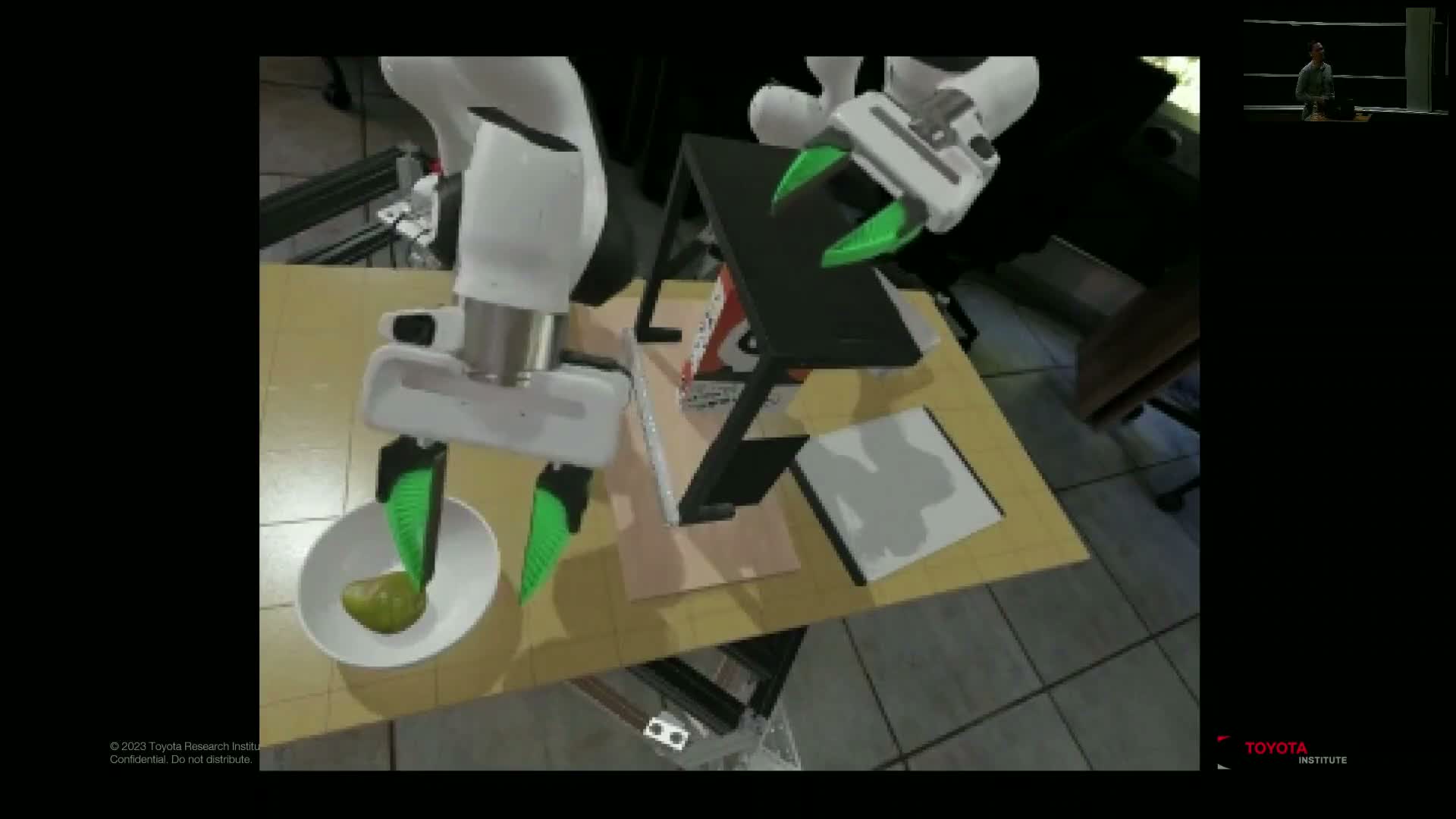

Simulation and tactile sensing augment real-world training and evaluation pipelines

Because physical evaluation is expensive and robots are limited resources, large-scale evaluation and some data generation are performed in simulation using realistic environments and physics engines (e.g., Drake).

Simulation benefits:

- Enables hundreds of thousands of rollouts for benchmarking.

- Supports internal multi-task benchmarks and rapid automated evaluation across dozens of behaviors, accelerating development and hyperparameter search.

Sensor modalities and conditioning:

- Non-visual sensors (tactile membranes, gel or air-filled with embedded cameras) produce dense latent observations that the same visual encoder machinery can condition on.

- This enables touch-aware and contact-sensitive behaviors (e.g., tightening bottle caps) without major code changes.

Combining sim and multiple sensor modalities increases training fidelity and enables richer conditioning beyond cameras.

Out-of-distribution shifts produce brittleness with characteristic failure modes

Policies trained from scratch on limited datasets can be brittle under modest distribution shifts (changed camera types, altered optics, scratched parts, background changes).

Symptoms of shift:

- Incorrect grasp placements, jerky or hesitant motions, mode collapse where the policy gets stuck in a single mode.

- Extreme shifts can cause random or flailing motions and catastrophic failures; intermediate shifts often show degraded or halting sequences before failure.

Practical remedies:

- Augment training with targeted demonstrations that show recovery behaviors.

- Add visual diversity during data collection.

- Iteratively patch failures by collecting additional teleop data demonstrating desired recovery transitions.

Data curation practices—short memory, multimodality, pauses, observability, and intentional imperfection—are crucial for robustness

Data quality and collection protocols strongly determine policy robustness.

Guidelines:

- Short implicit memory (the “goldfish” effect) means demonstrations should avoid long idle pauses, which teach the policy to remain still.

-

Long-horizon multimodal decisions require explicit demonstration of alternative modes and recovery transitions to avoid indecision.

-

Observability alignment: operators should teach through the robot’s sensors to avoid leaked information the robot cannot see.

- Include controlled variability and small mistakes so the policy learns recovery behaviors, but avoid so many errors that the policy adopts suboptimal strategies.

Because robustness via added variation is laborious, scaling solutions are required to avoid per-task manual patching.

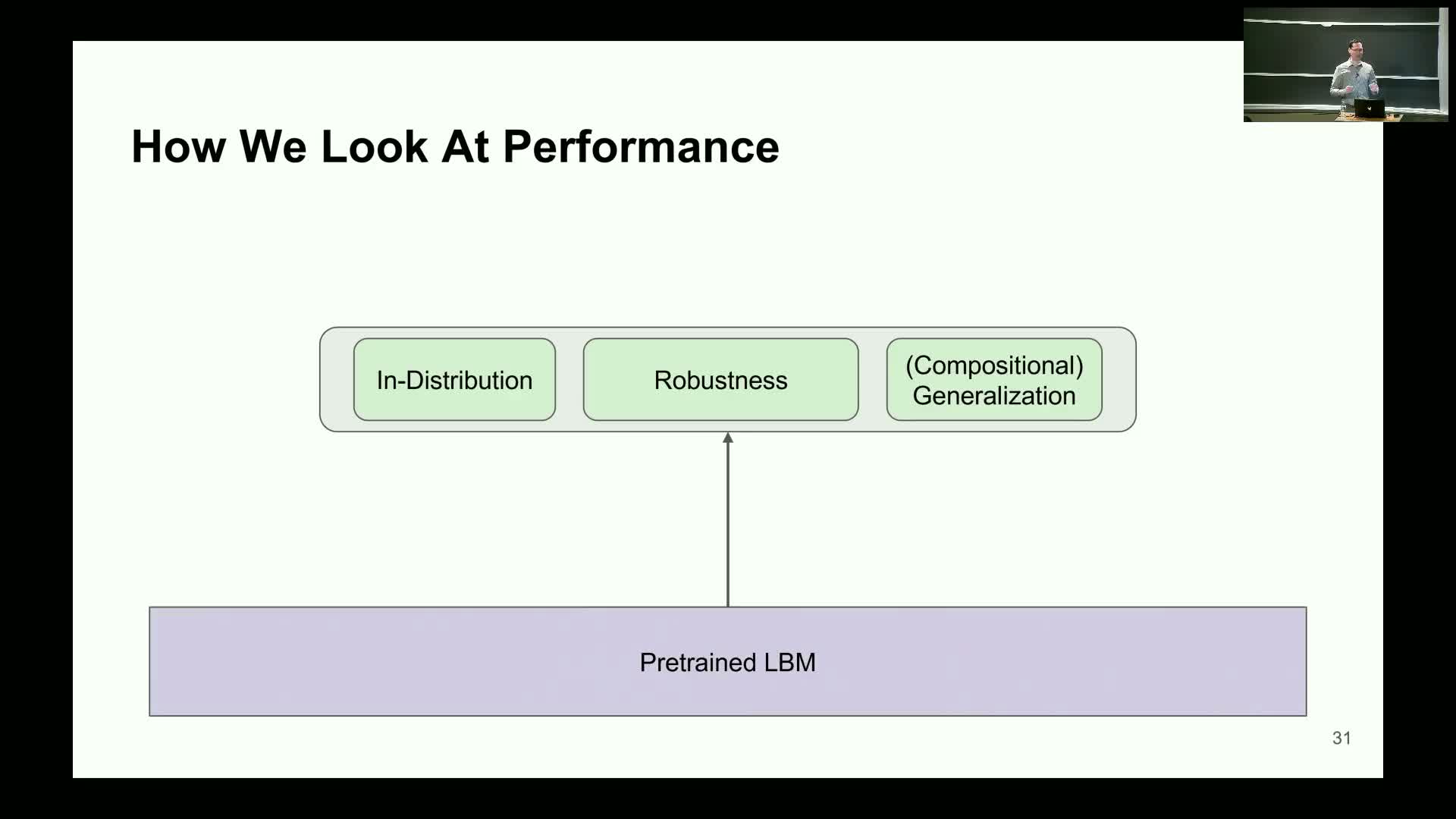

Scaling to multitask generalist models leverages diverse datasets and pretrained visual-language models

To move beyond single-behavior policies, the prevailing approach is to train larger multitask models conditioned by language or goal signals and to leverage diverse data sources:

- Other robots’ logs and video datasets

-

Pretrained visual-language models (VLMs) as foundational encoders

Practical pattern:

- Use pretrained VLMs for rich multimodal representations, combine them with action heads via cross-attention or conditioning, then fine-tune on action-labeled robot data to improve zero-shot or few-shot generalization.

Main limitation: scarcity of large-scale robot action datasets, so transfer from large visual-language pretraining and integration of video/action datasets are central to current scaling strategies. Fine-tuning remains important to align generalist models to specific robot stations or tasks.

Generalist versus specialist tradeoffs and emergent cooperative behaviors

Generalist models trained on broad multimodal datasets can exhibit compositional generalization—combining primitives to solve novel tasks—and sometimes show emergent recovery behaviors not seen in from-scratch specialists.

Practical observations:

- Generalists can be idiosyncratic, less steerable, or not perfectly cooperative out-of-the-box.

-

Fine-tuning on task-specific data is often required for reliably controlled, demo-quality deployments.

Strategy: use generalists as a strong foundation for transfer, then build specialists via fine-tuning when peak reliability is required. Engineering effort focuses on improving steerability, data efficiency, and fine-tuning recipes to preserve pretraining benefits.

Denoising dynamics are implementation-specific and are decoupled from predicted action trajectories using alternative training objectives

The denoising path taken during diffusion or flow-matching optimization is an implementation detail distinct from the action trajectories the policy outputs to the robot.

Practical design principle:

- Decouple optimization dynamics (diffusion vs flow matching) from the action-space prediction target (e.g., waypoint sequences).

- Treat denoising or matching dynamics as a black-box sampler for the learned action distribution.

This separation helps ensure idiosyncrasies of the denoising optimizer do not alter the semantics of executed robot behaviors.

Long-term research goal: build general-purpose, scientifically-understood robotic systems and scale research teams and collaborations

The strategic aim is to develop scientific understanding and engineering practices for training general-purpose robotic systems using AI, emphasizing transferability, reproducibility and open research.

Required components:

- Large multimodal pretraining and pretrained backbones

- Improved evaluation infrastructure and extensive simulation benchmarks

- Practical data-collection pipelines and instrumented teaching workflows

- Collaborative academic-industrial efforts to scale expertise and datasets

Building robust generalists that can be fine-tuned into specialists and creating community benchmarking resources will accelerate progress toward capable deployed robotic systems. Organizations engaged in this research often seek collaborations and talent to expand experimental and evaluation capacity.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: