MIT 6.S184 - Lecture 6 - Diffusion for Protein Generation

- Overview of diffusion models applied to protein generation

- Motivation for AI in protein design and the cost problem in biology

- Basic protein modeling pipeline: sequence → structure → function and multimodality

- Recent algorithmic advances: AlphaFold, inverse structure-to-sequence models, and diffusion methods

- Commercial and translational impact of protein generative models

- Desired properties for a protein generative model

- Challenges of naively diffusing Cartesian coordinates for proteins

- Frame-based geometric representation: grouping rigid atom sets into SE(3) frames

- Scaling considerations: architectures, equivariance, and atom grouping

- Diffusion on manifolds for frames: Brownian motion on SO(3) and forward/reverse processes

- Model architecture: spatial and positional attention plus equivariant scoring

- Generation pipeline and realism checks using sequence prediction validation

- Empirical results: Frame diffusion yields high-quality, diverse and novel structures but functional validation remains next

- Flow matching variant and its advantages for manifold generation

- Practical initialization and sequence length handling in protein generative models

- RFdiffusion: pretraining plus diffusion for large-scale conditional structure generation

- Conditional generation primitives: symmetry, binder design, inpainting and classifier guidance

- Experimental validation and empirical success rates for diffusion-based binder design

- Codesign and Multiflow: joint generation of sequence and structure

Overview of diffusion models applied to protein generation

Diffusion models are being applied to the protein design pipeline to generate novel protein structures and enable downstream sequence design for functional molecules.

The objective of this research direction is to produce high-quality, diverse, and synthesizable protein structures that can be converted into sequences and experimentally validated.

Advances combine generative diffusion machinery with pre-trained structure-prediction networks and geometry-aware representations to bridge structure generation and practical design.

This integration targets accelerating molecular discovery timelines by enabling computational generation of candidate proteins prior to wet-lab validation.

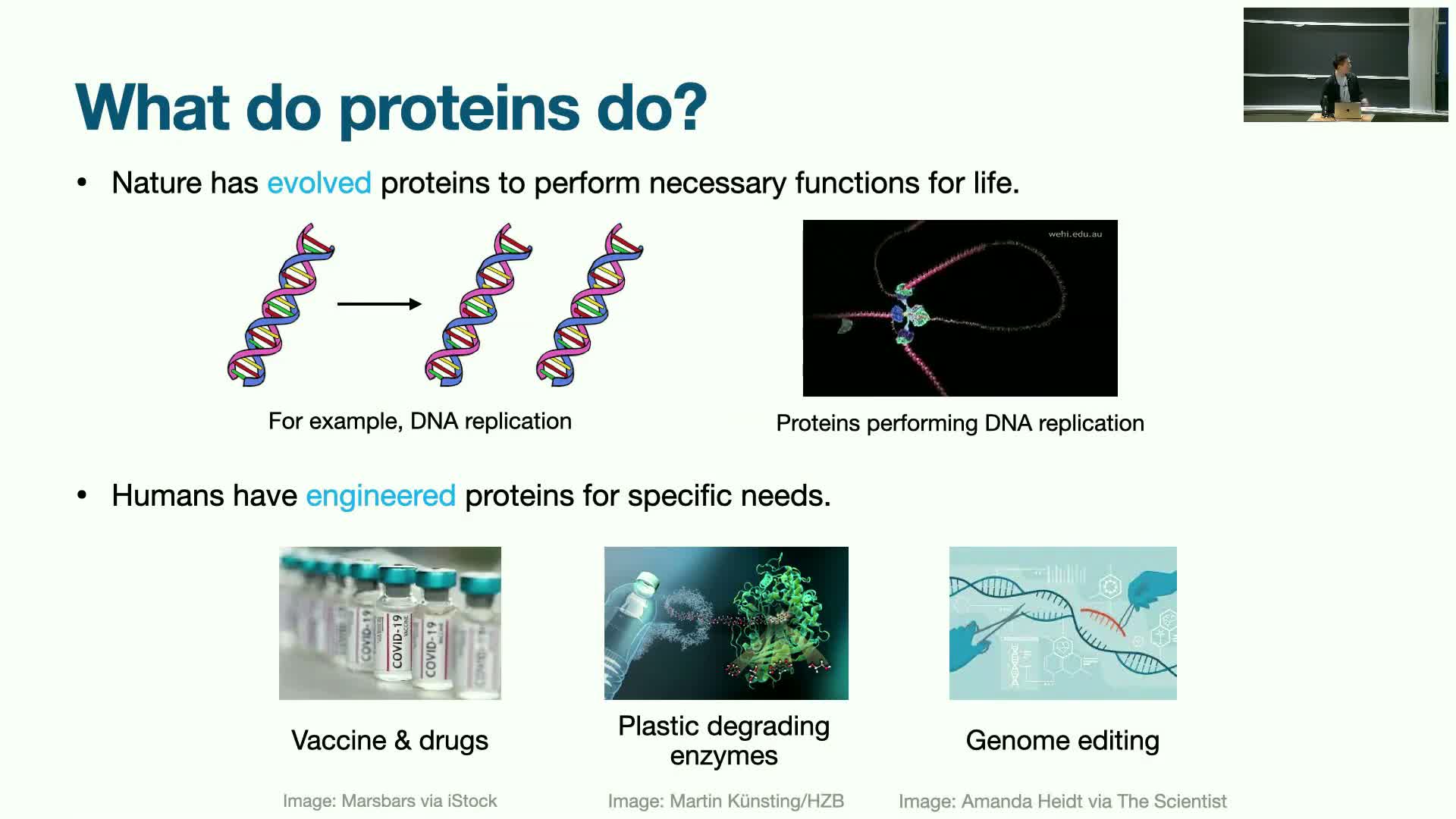

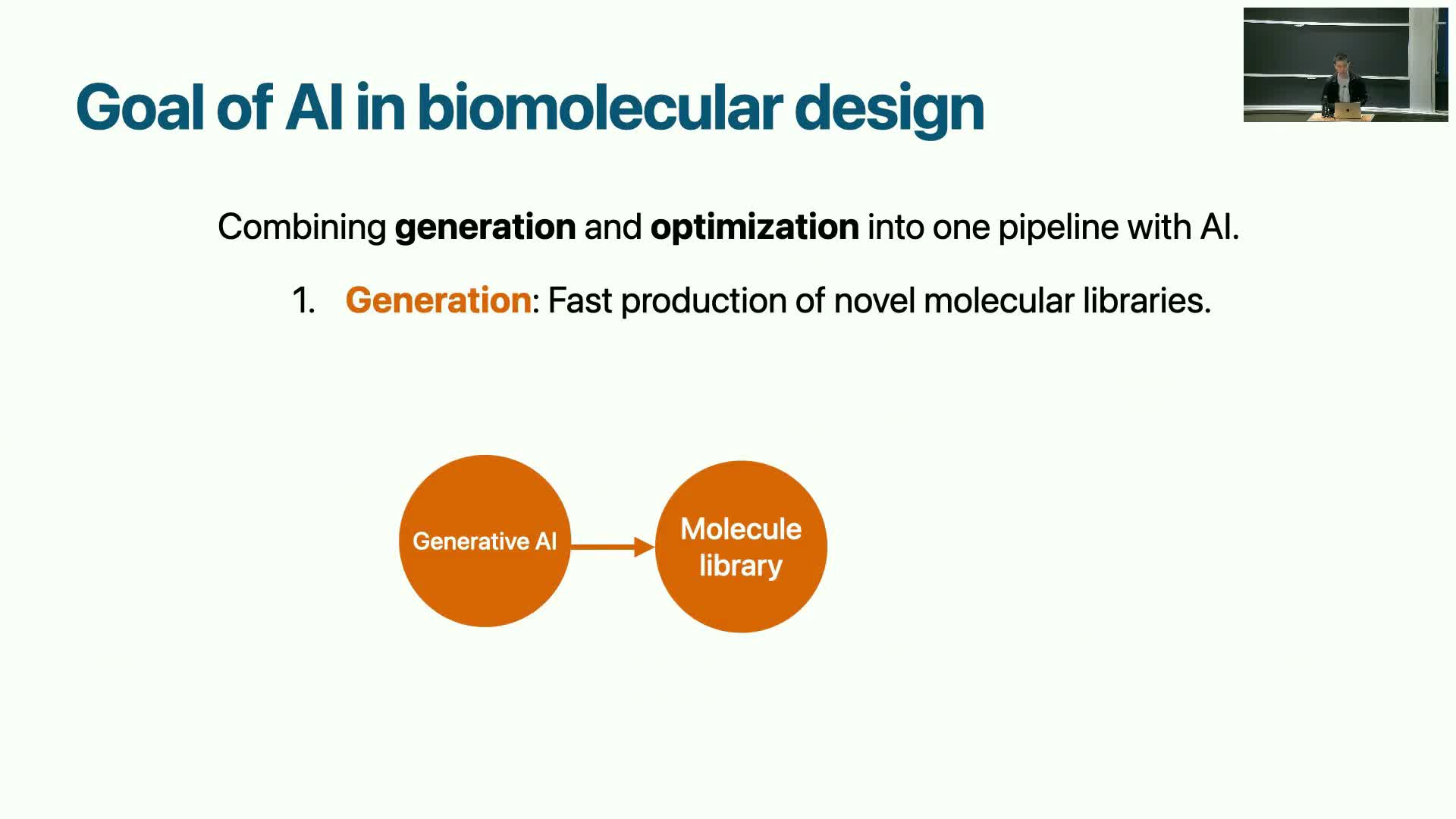

Motivation for AI in protein design and the cost problem in biology

Protein engineering addresses many urgent problems in health and materials, yet conventional drug discovery is slow and expensive — often requiring about a decade and billions of dollars per new drug.

Decreasing compute costs combined with rising biological development costs create a gap where algorithmic acceleration can have outsized impact.

AI methods aim to compress design cycles by rapidly proposing candidate molecules for experimental screening, enabling iterative loops between computation and wet-lab optimization.

Goals and benefits:

-

Reduce time-to-discovery and overall development cost.

-

Broaden addressable biological problems by automating parts of molecular design.

- Support fast computational → experimental cycles for rapid iteration and optimization.

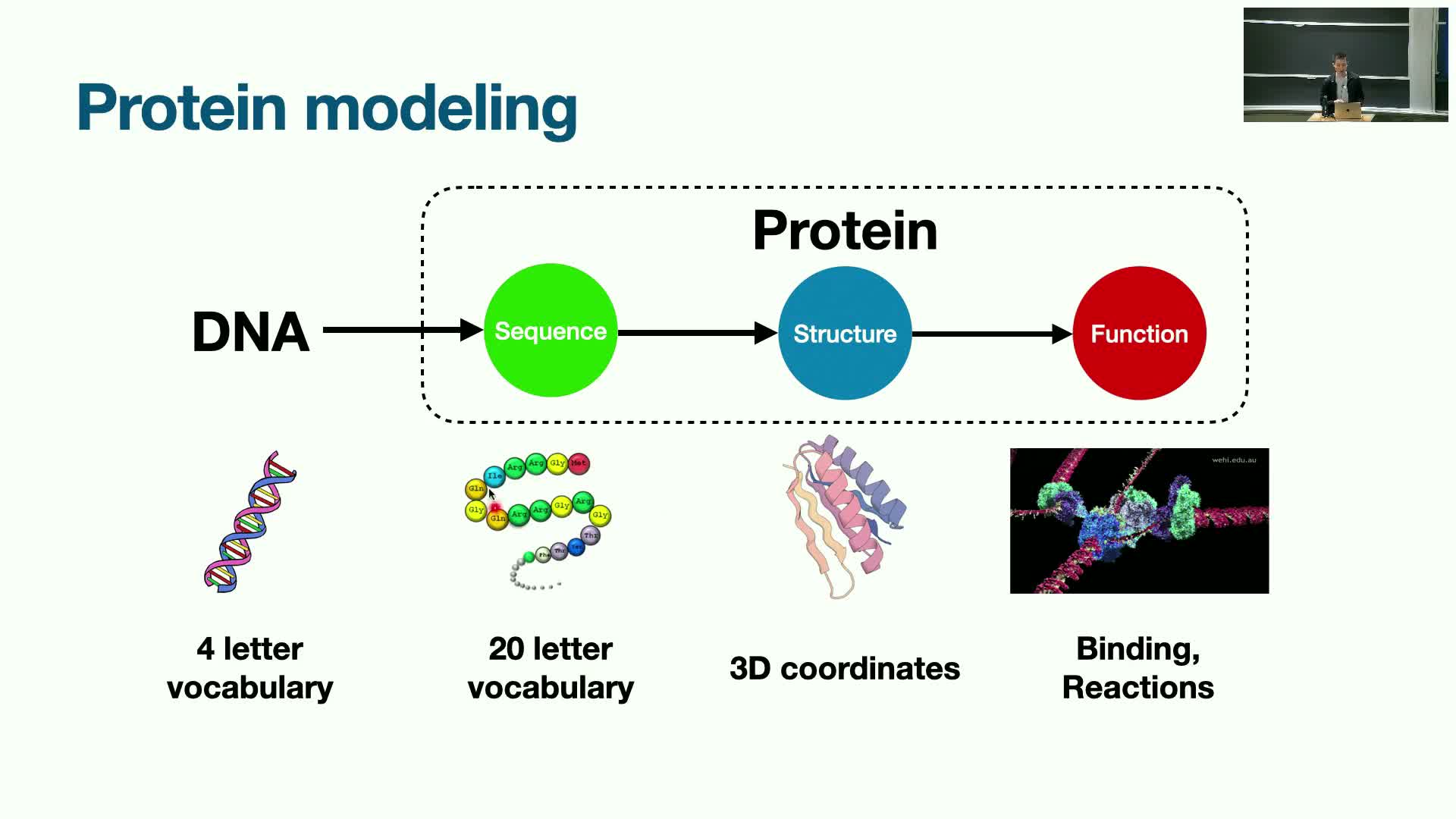

Basic protein modeling pipeline: sequence → structure → function and multimodality

Proteins arise via the central dogma: DNA → amino-acid sequence → folded 3D structure that determines biological function.

This mapping contains multiple data modalities that make modeling inherently multimodal:

-

Discrete sequences: a 20-letter amino-acid vocabulary.

-

Continuous 3D coordinates: atomic and residue geometries.

-

Dynamic functional behaviors: conformational changes, binding dynamics.

Working at the protein (sequence/structure) level provides a higher-level abstraction for engineering function than designing directly in nucleotide space.

Effective computational design must therefore:

- Handle both discrete and continuous representations.

- Account for geometric and dynamical constraints that govern folding and function.

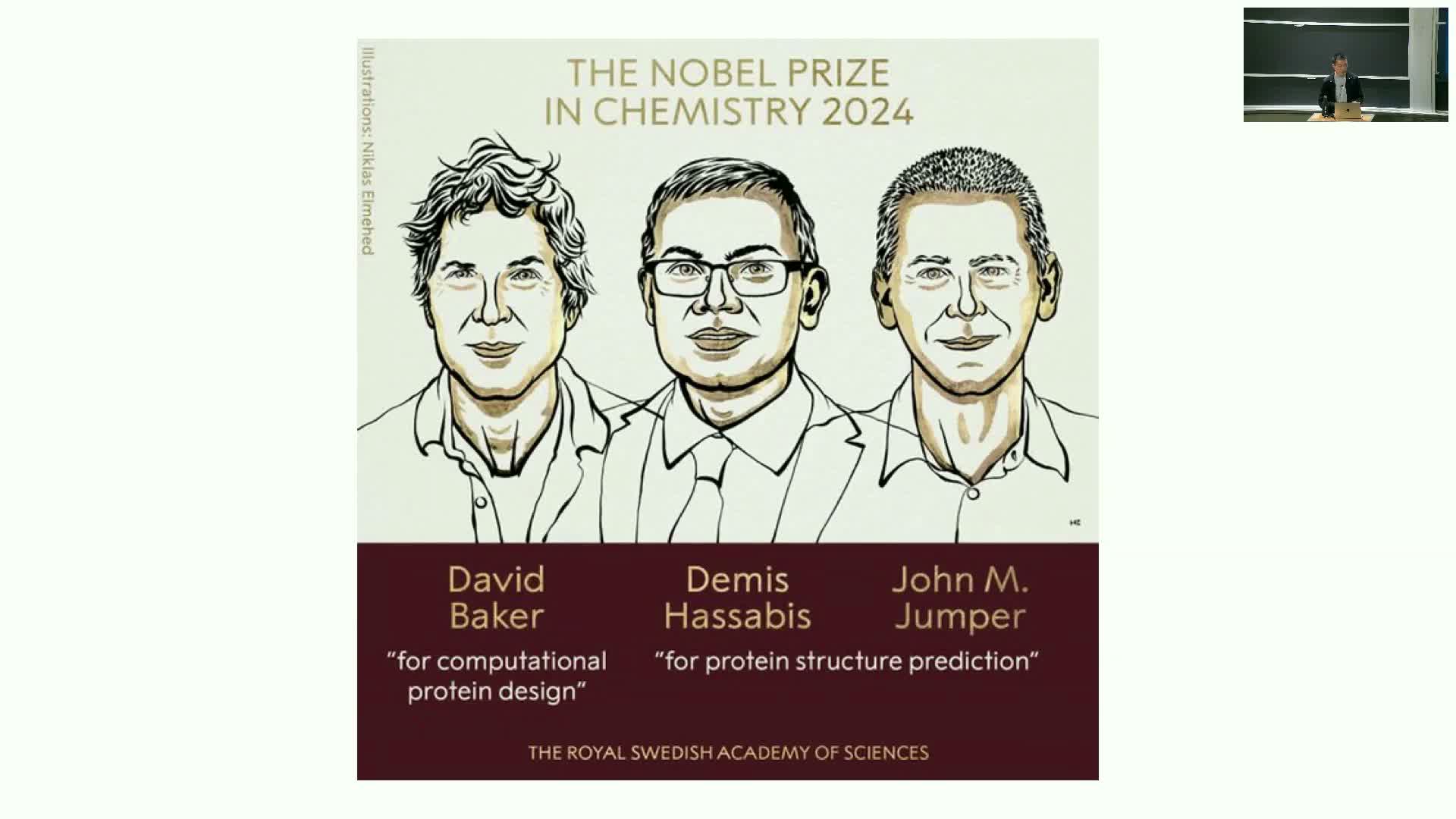

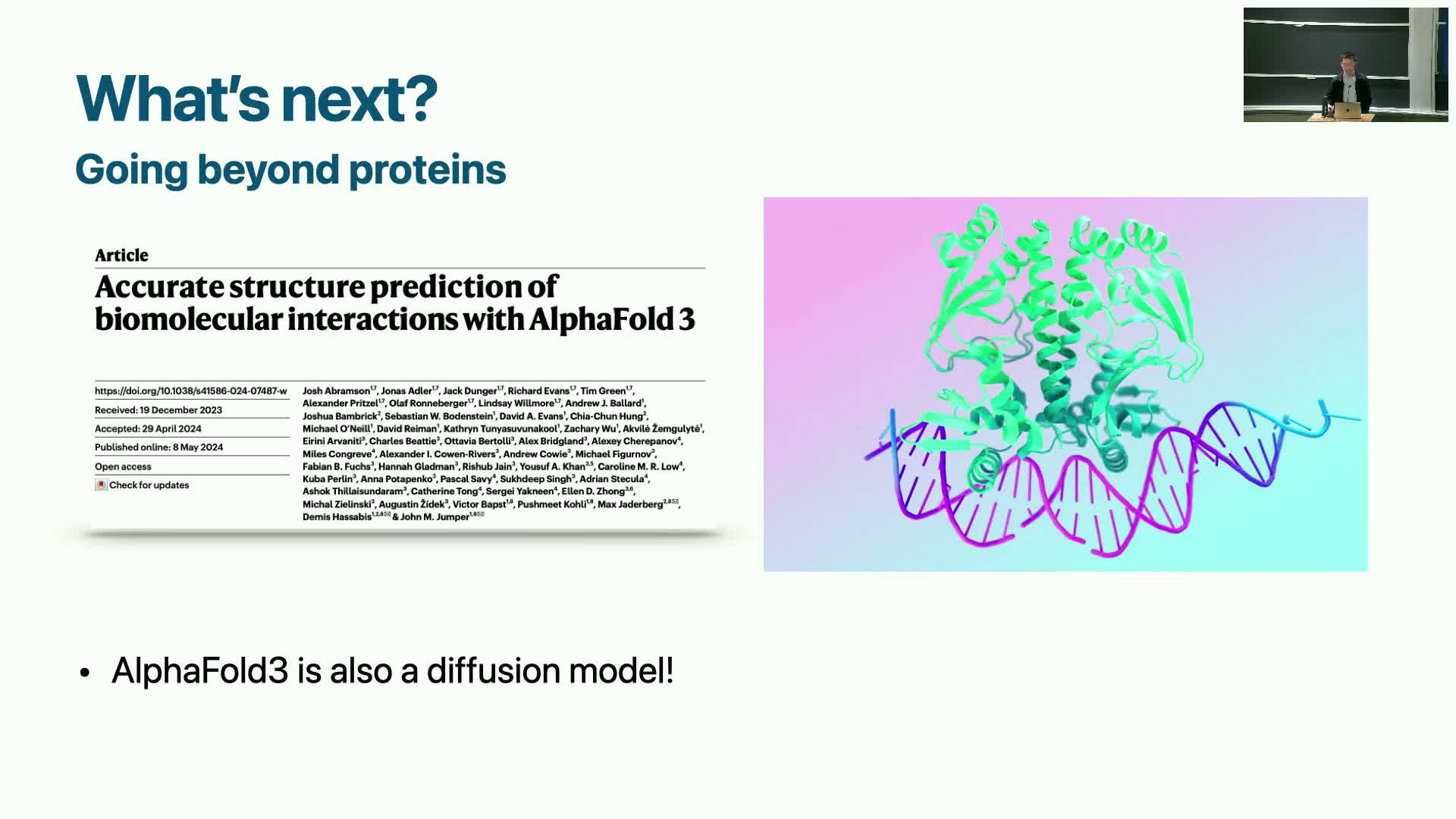

Recent algorithmic advances: AlphaFold, inverse structure-to-sequence models, and diffusion methods

Three classes of algorithms underpin modern de novo protein design:

-

Structure prediction (e.g., AlphaFold) — maps sequence → structure.

-

Inverse structure → sequence approaches — use graph neural networks or autoregressive models to propose sequences for a target fold.

-

Diffusion-based structure generation — directly generates novel 3D structures conditioned on functional motifs.

Key points:

-

AlphaFold-style prediction dramatically improved ability to evaluate candidate sequences by predicting folded structures.

-

Inverse models allow mapping from desired structures back to sequences.

-

Diffusion models form the generative component of a function → structure → sequence pipeline by producing novel folds under constraints.

These combined developments have enabled practical protein-design pipelines and contributed to major recognitions in computational biology and chemistry.

Commercial and translational impact of protein generative models

Generative structure models have catalyzed startups and commercial efforts focused on protein therapeutics and molecular design.

Trends and impacts:

- Notable spinouts and large funding rounds have emerged from academic and industrial work.

-

Pretrained generative architectures and diffusion-based approaches are being productized to design binders, enzymes, and other therapeutics.

- Venture-scale companies and collaborations with pharmaceutical partners use these models to accelerate design workflows.

This commercialization highlights both the scientific maturity of the methods and their potential real-world impact on drug discovery pipelines.

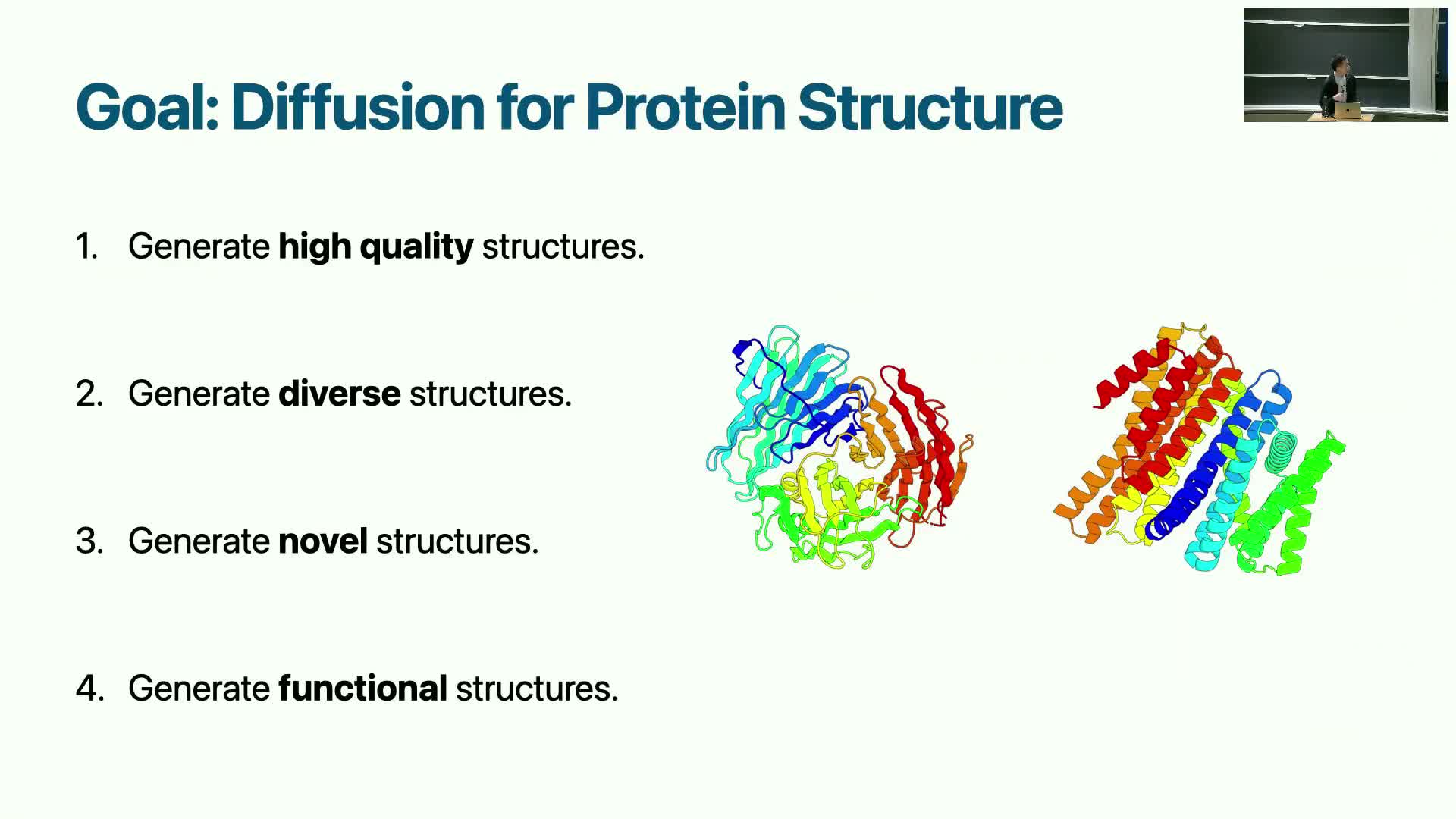

Desired properties for a protein generative model

A practical protein generative model must satisfy several requirements:

- Produce a single high-fidelity structure for each sample.

-

Sample a diverse distribution of plausible folds (avoid mode collapse).

-

Generalize to novel structures beyond the training set.

- Ultimately generate designs that perform desired biological functions.

Constituent definitions:

-

Quality: physically realistic 3D geometries that respect bond constraints and avoid steric clashes.

-

Diversity: broad coverage of fold space rather than a few repeated modes.

-

Functional performance: conditioning or optimization toward binding, catalysis, or other biochemical objectives plus experimental validation.

Balancing these motivates geometry-aware generative architectures and conditional-generation mechanisms.

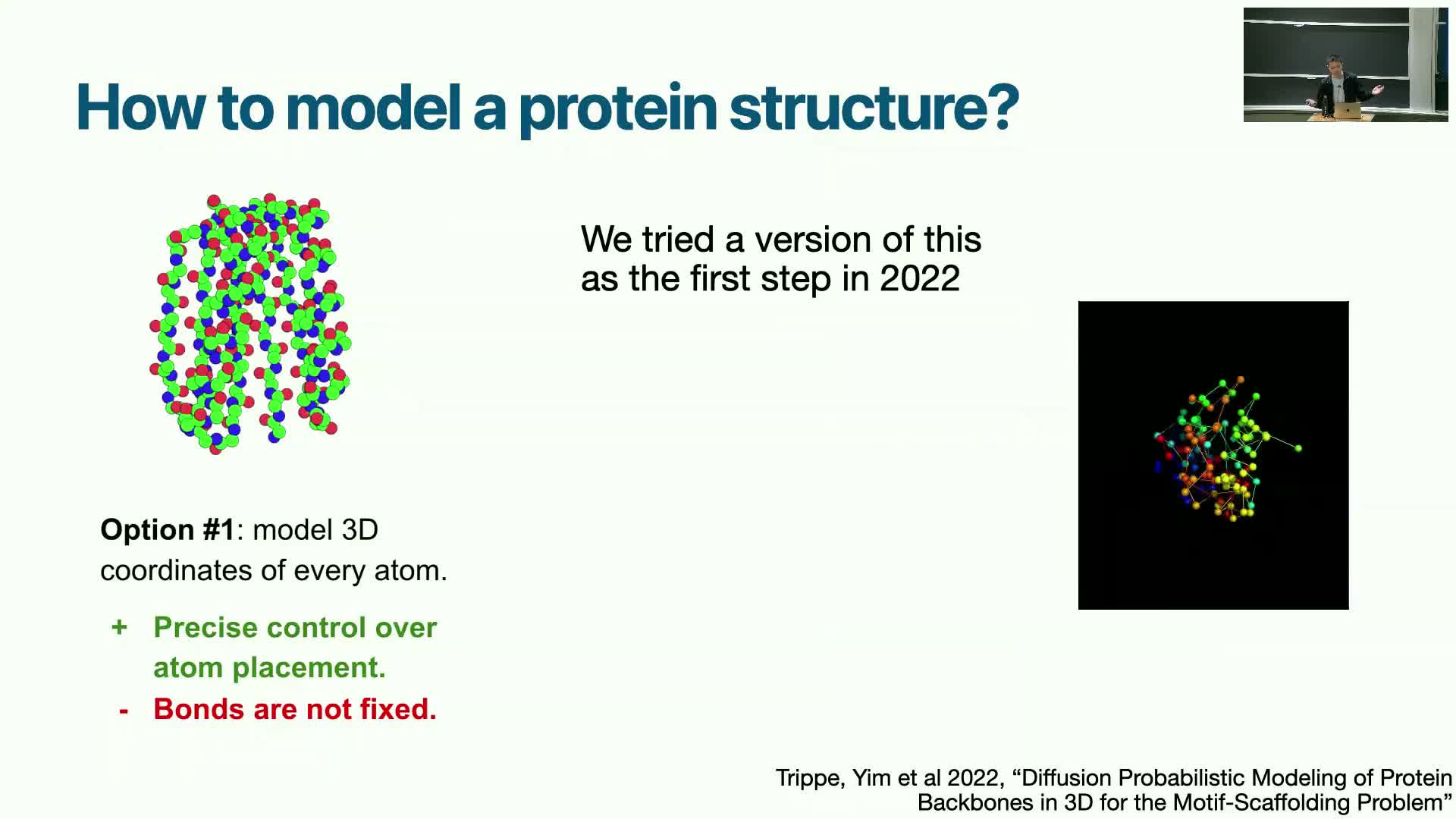

Challenges of naively diffusing Cartesian coordinates for proteins

Applying standard Gaussian-space diffusion directly to every atomic Cartesian coordinate encounters severe difficulties because proteins must satisfy strict biophysical constraints:

-

Unconstrained coordinate noise tends to create steric clashes and broken bond lengths/angles that are difficult to recover during reverse diffusion.

- Training such unconstrained models at scale is challenging; early attempts that treated all atom positions independently worked to some degree but struggled to scale and reliably produce physically plausible structures.

Conclusion: respecting intrinsic geometric structure is critical to achieve scalable, high-quality generation.

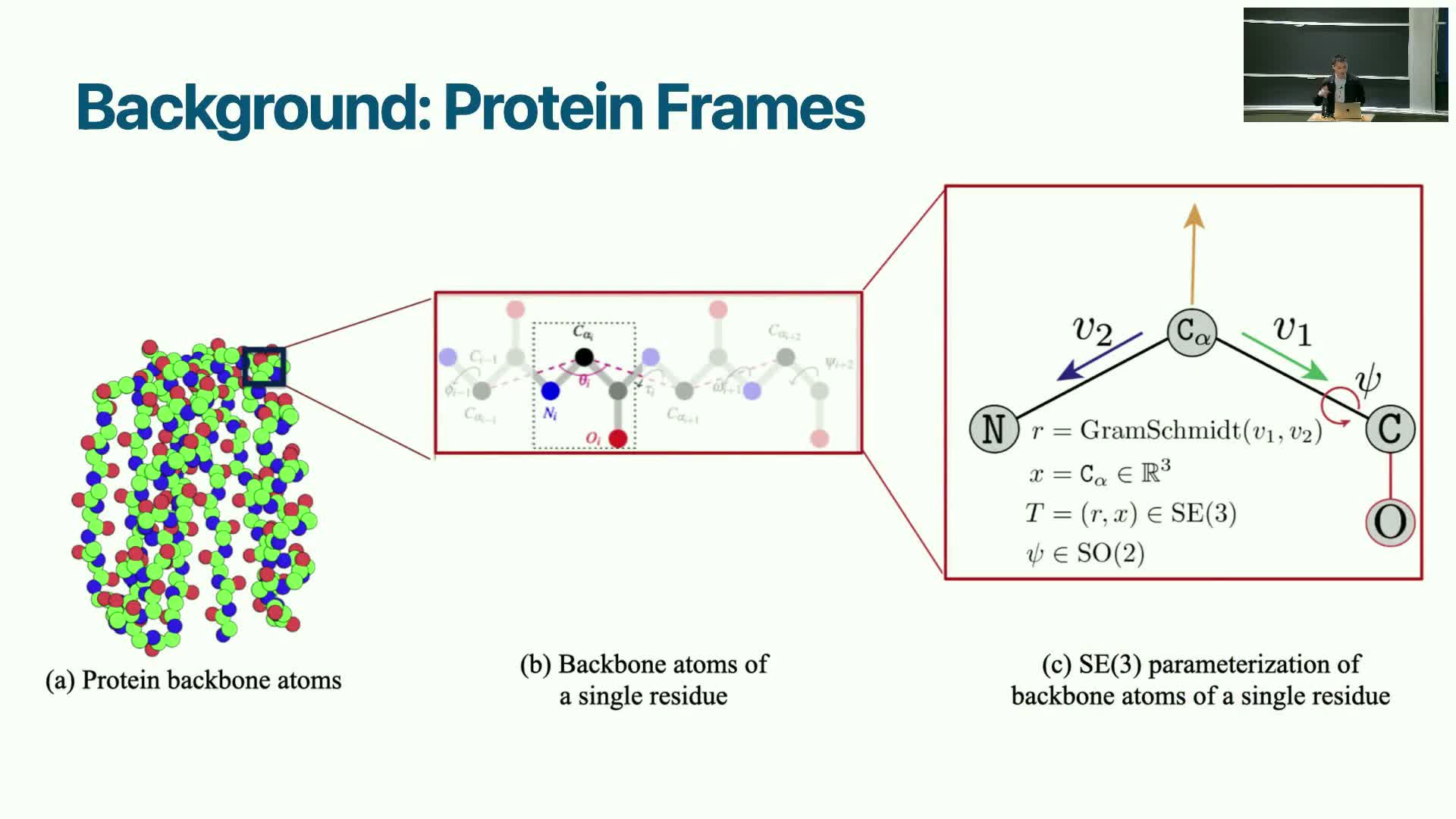

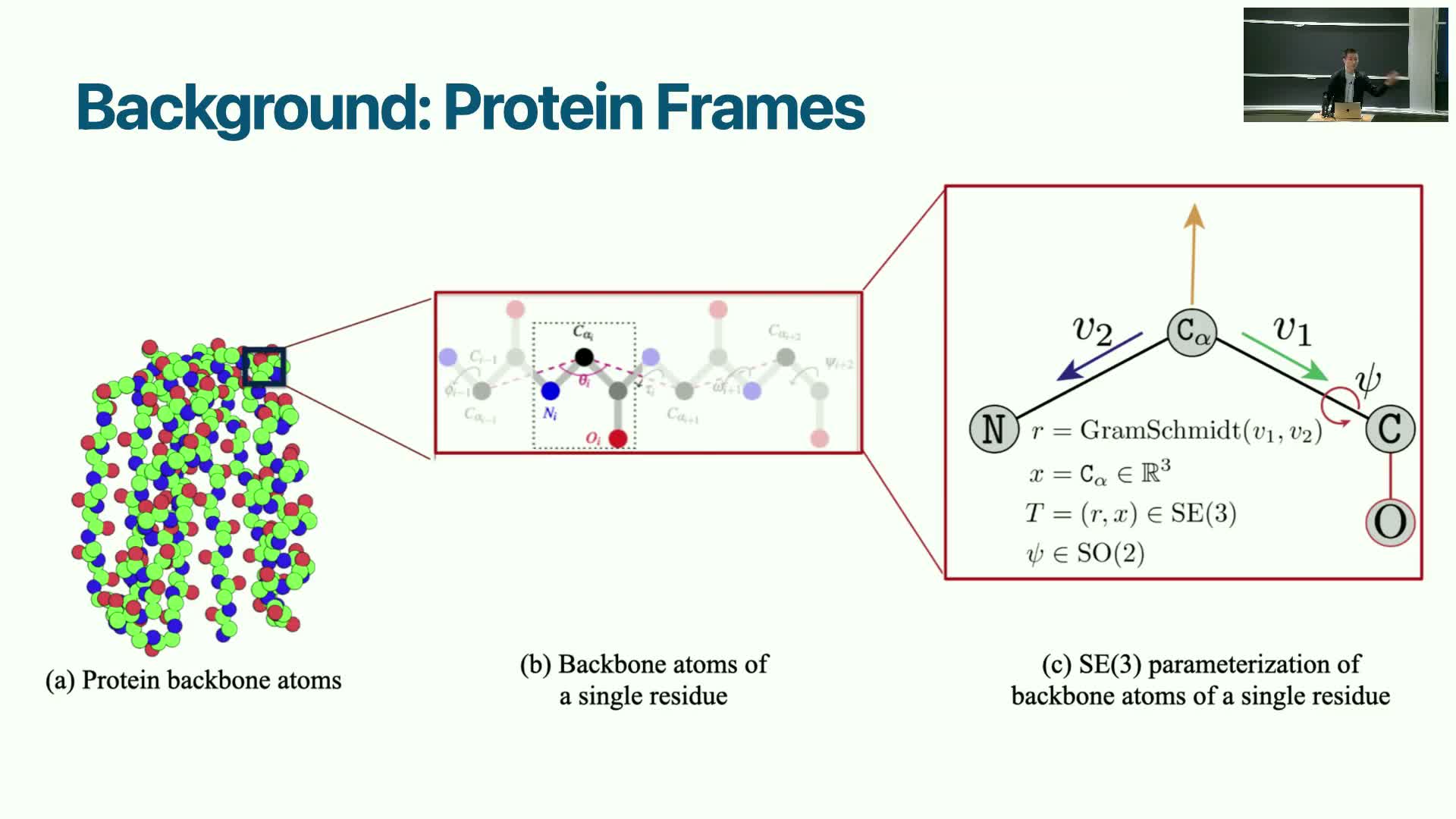

Frame-based geometric representation: grouping rigid atom sets into SE(3) frames

Modeling proteins as chains of rigid residue frames provides a compromise between unconstrained Cartesian diffusion and diffusion over internal angle parameterizations.

Concept and representation:

- Each residue is represented by a rigid frame (an element of SE(3)) defined from key atom vectors (for example, vectors from the Cα to neighboring backbone atoms).

- This preserves local bond geometry while exposing rotation and translation degrees of freedom for diffusion.

Benefits:

- Keeps bond lengths and local geometry stable.

- Reduces effective dimensionality compared to per-atom coordinates.

- Allows precise control over global placement through frame translations and rotations.

Frames enable diffusion on a heterogeneous manifold composed of translations and rotations that align naturally with protein kinematics.

Scaling considerations: architectures, equivariance, and atom grouping

Practical model-scaling choices significantly affect performance:

-

Graph neural network models trained on limited compute can be effective at modest scales.

- Large Transformer-based architectures scaled by industry labs sometimes achieve strong performance without explicit equivariant constraints.

Computational trade-offs and techniques:

- Grouping atoms into residue frames reduces per-token cost but only yields constant-factor savings; very long proteins still pose challenges.

- Optimizations such as local attention, grouped attention, FlashAttention, and other transformer-scale tricks mitigate cost.

- The tradeoff between explicit geometric equivariance (e.g., SE(3)-aware designs) and brute-force scaling remains an active research question.

For many geometry-sensitive tasks, exploiting equivariance or SE(3)-aware design remains advantageous to maintain physical fidelity.

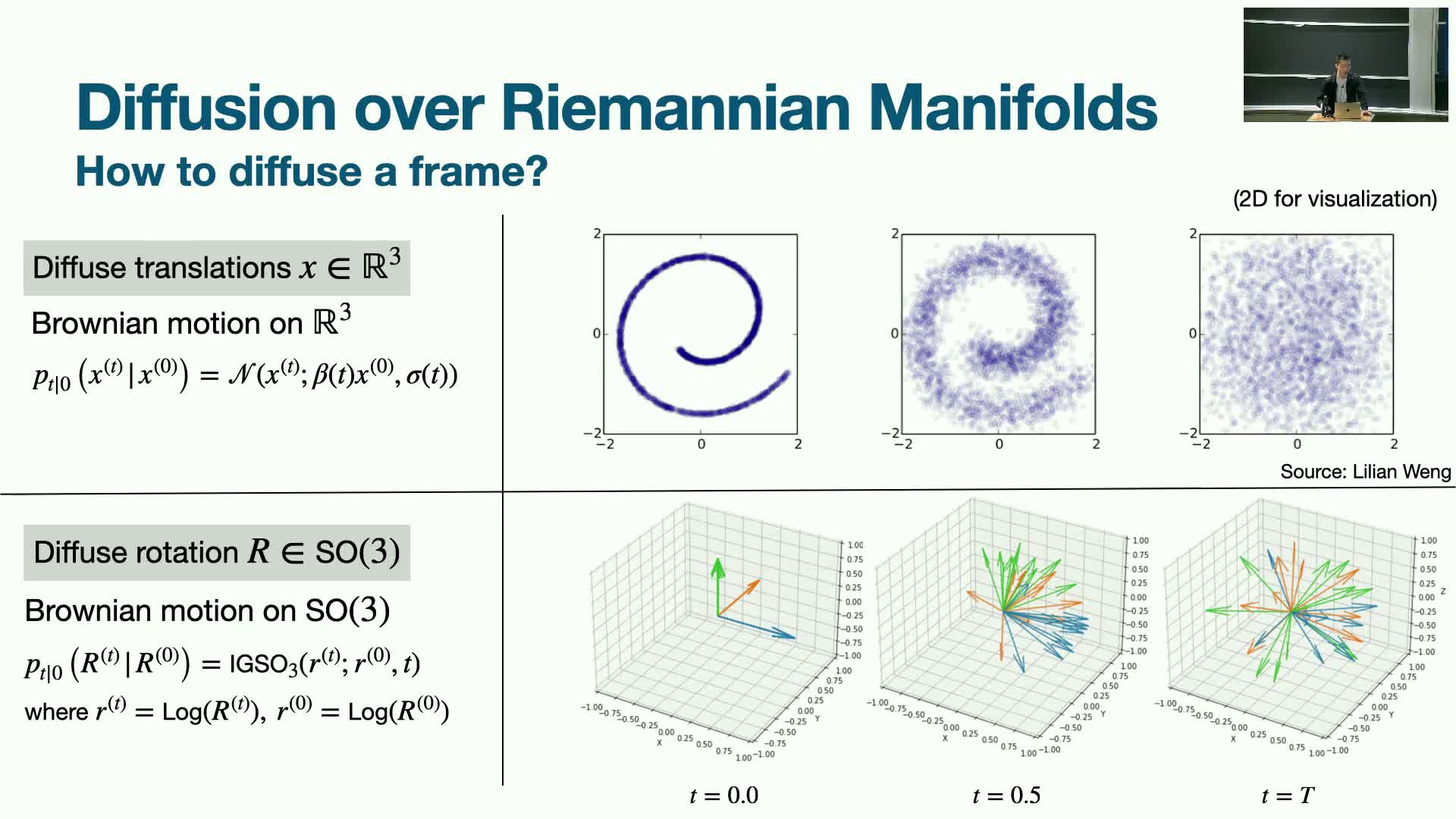

Diffusion on manifolds for frames: Brownian motion on SO(3) and forward/reverse processes

Diffusion over residue frames requires formulating forward noising and reverse denoising on non-Euclidean manifolds:

-

Translations are diffused in Euclidean space.

-

Rotations are diffused on SO(3) using manifold Brownian motion.

Mathematical and implementation considerations:

- The forward process approaches an isotropic distribution on the rotation manifold at large noise times.

- Score or velocity fields used in reverse sampling must be defined with manifold-aware exponential and logarithmic maps.

- This yields analogues of Gaussian diffusion with kernels appropriate to SO(3), and rigorous geometric handling ensures the generative process behaves intuitively like Euclidean diffusion while respecting rotational structure.

Implementing manifold diffusion requires adapting stochastic differential equation formulations and score estimation to Riemannian settings.

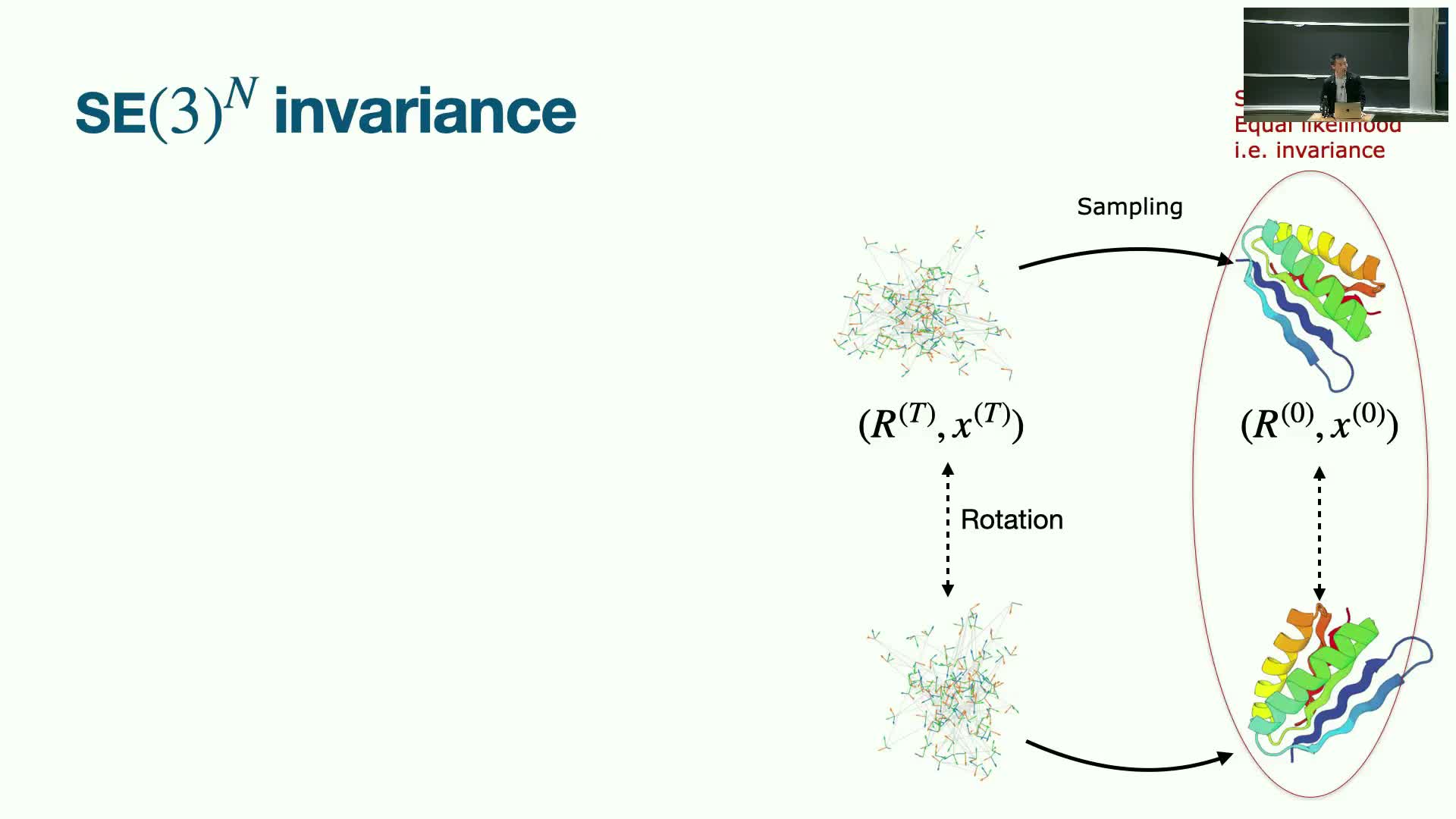

Model architecture: spatial and positional attention plus equivariant scoring

High-quality frame diffusion models combine the ability to attend over sequence positions with spatial attention that accounts for 3D proximity and long-range interactions.

Architectural ingredients:

- Neural networks predict an equivariant score/velocity field so outputs rotate appropriately under input rotations.

-

Translation invariance is preserved by centering frames during processing.

- Ideas from advanced protein predictors (e.g., AlphaFold2-style spatial attention) capture local geometric structure and global dependencies simultaneously.

- Iterative denoising steps progressively refine frame embeddings and generate final structures.

Guarantees such as equivariance and invariance are crucial to ensure generated structures are physically consistent and semantically correct under rotations/translations.

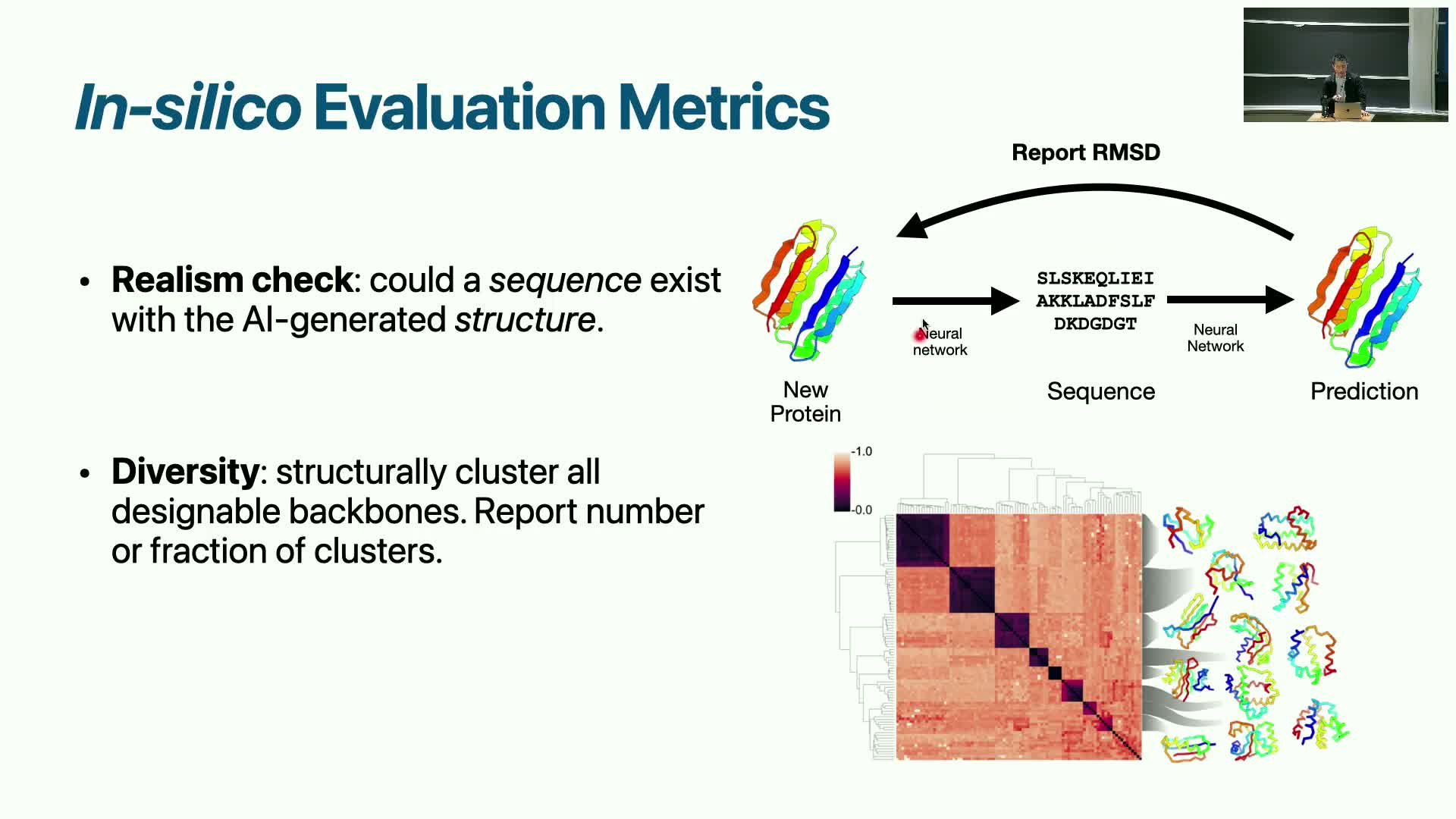

Generation pipeline and realism checks using sequence prediction validation

Generated structures are validated by testing whether a plausible amino-acid sequence exists that folds into the structure.

Typical validation pipeline (ordered):

- Use a sequence predictor to propose a sequence for the generated structure.

- Run a structure-prediction model (e.g., AlphaFold2) to evaluate whether that sequence refolds to the generated structure.

- Declare a successful realism pass when the predicted fold has low RMSD compared to the target generated structure.

Diversity assessment:

- Cluster generated structures using RMSD normalized by length.

- Count distinct fold clusters to estimate coverage of structural space.

These evaluation steps convert geometric outputs into experimentally actionable candidates by ensuring a sequence can realize the designed fold and that candidate sets include novel and diverse solutions.

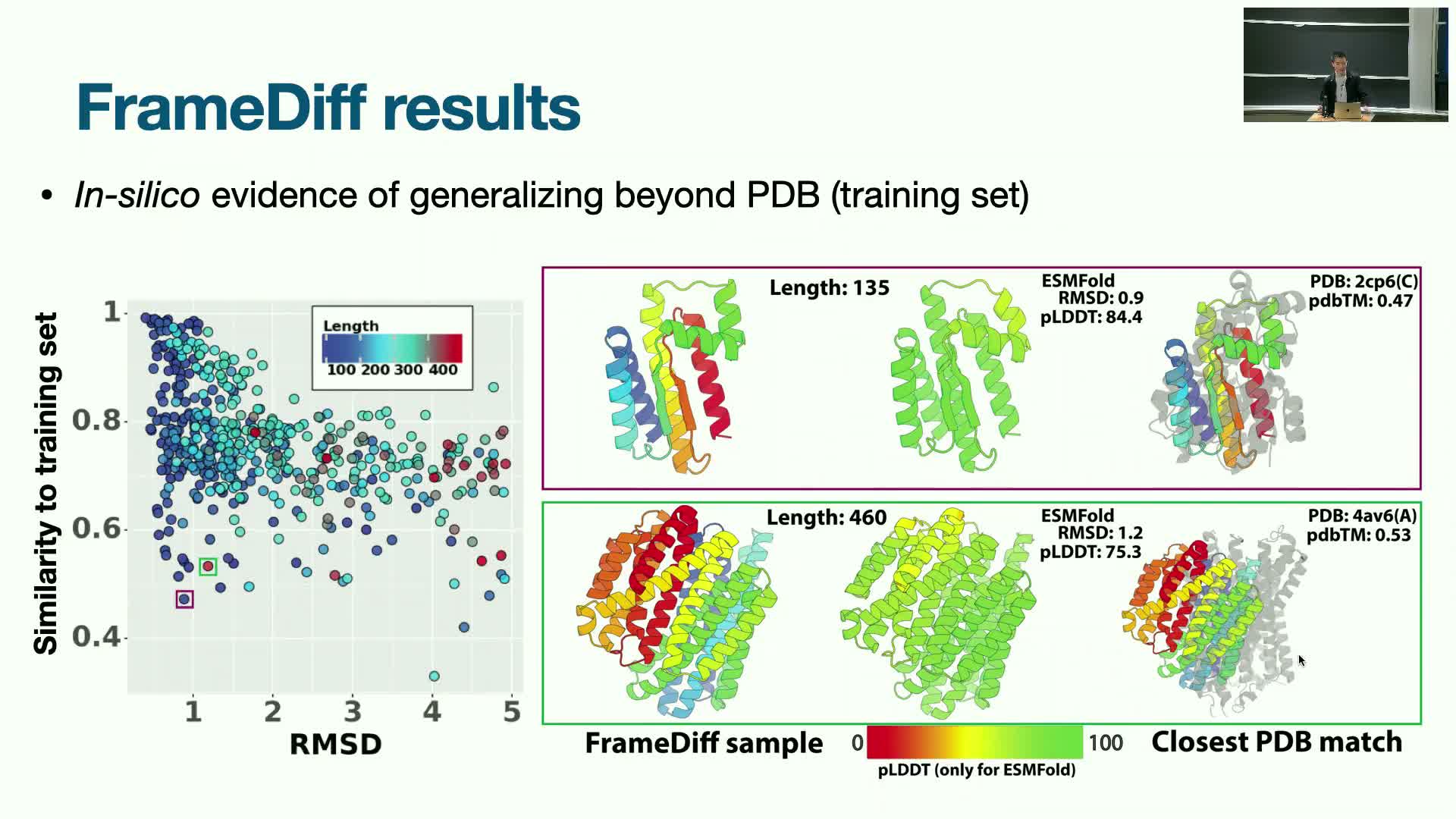

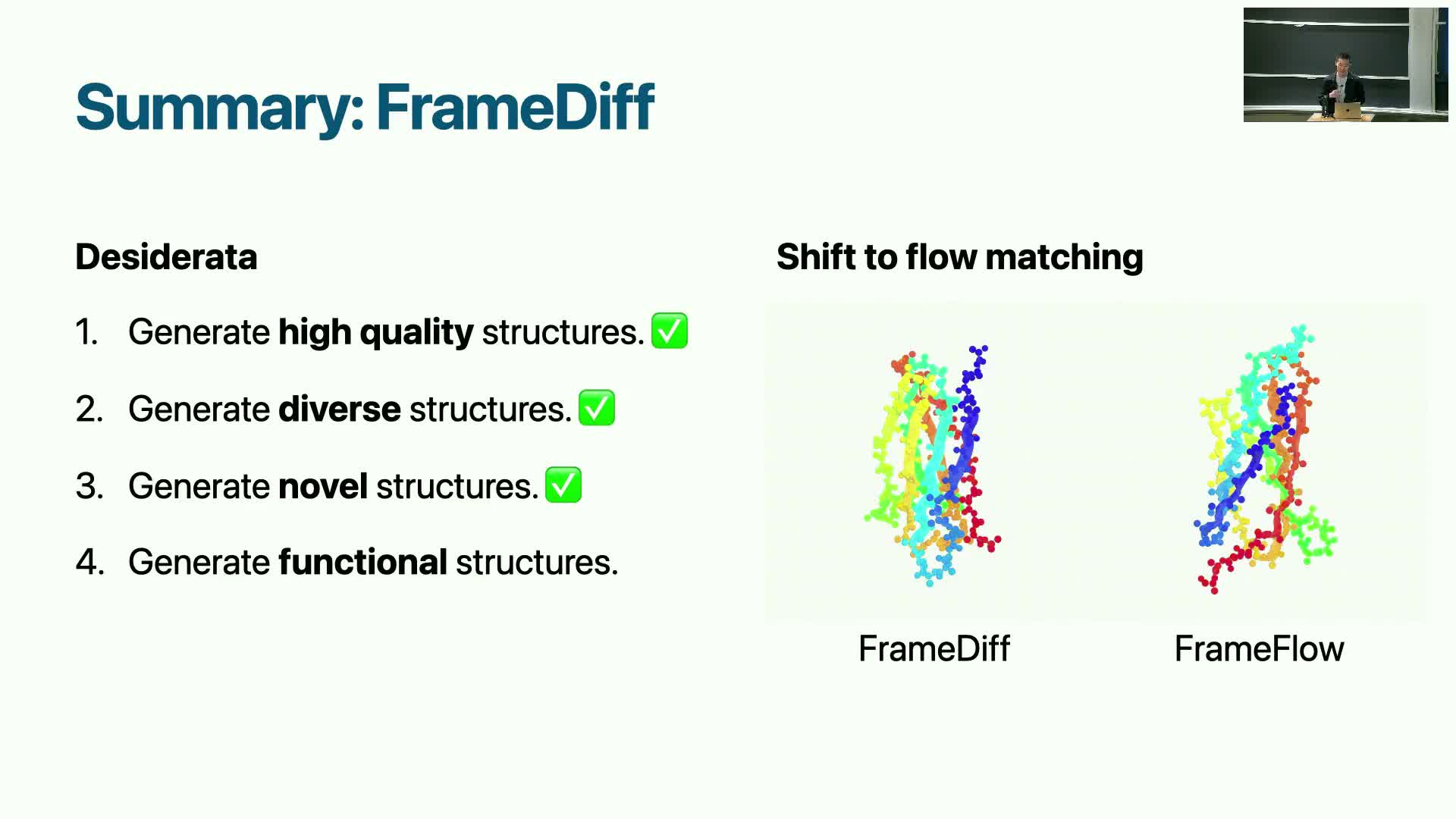

Empirical results: Frame diffusion yields high-quality, diverse and novel structures but functional validation remains next

FrameDiff demonstrated the ability to generate high-fidelity 3D structures that are diverse and novel relative to training data, with qualitative and quantitative indicators of generalization beyond the dataset.

Observed behaviors and limitations:

- Performance tends to degrade for longer proteins, indicating model and scaling limitations for very long chains.

- Many generated structures passed the realism check and clustered into multiple distinct folds.

Open challenges and directions:

- Achieving biochemical function (activity or binding) requires additional conditioning and downstream optimization.

- Subsequent methods have focused on adding conditional design capabilities and classifier-guided objectives.

Frame-based diffusion therefore satisfies quality, diversity, and novelty goals while motivating further work on functional conditioning and experimental integration.

Flow matching variant and its advantages for manifold generation

Flow matching replaces explicit stochastic diffusion with a deterministic, optimal-transport-like matching objective over trajectories.

Why flow matching is attractive for manifold data:

- It can be more naturally defined on Riemannian manifolds where no analytical noise kernel exists.

- Flow-matching simplifies training by directly regressing velocity fields between distributions along geodesics.

- Empirically, it has shown improved results for manifold-valued data such as SE(3) frames.

Practical benefits:

- Avoids some mathematical complications of defining Brownian kernels on arbitrary manifolds.

- Can yield more stable training and sampling, making it a competitive alternative to score-based diffusion for geometry-aware generative methods.

Practical initialization and sequence length handling in protein generative models

Protein generation models work with a pre-determined token length and positional encoding:

- The model is initialized with a chosen maximum length and receives positional encodings that indicate which residues to model.

- Typically, the model does not infer protein length implicitly during sampling without additional mechanisms.

Control mechanisms for output length:

- Constrain the generation length at initialization.

- Implement a learned length-sampling mechanism if variable-length outputs are required.

Role of attention and positional encodings:

- Help maintain contiguous chain relationships so residue i attends correctly to neighbors i±1.

- Enforce local bonding patterns and chain integrity during generation.

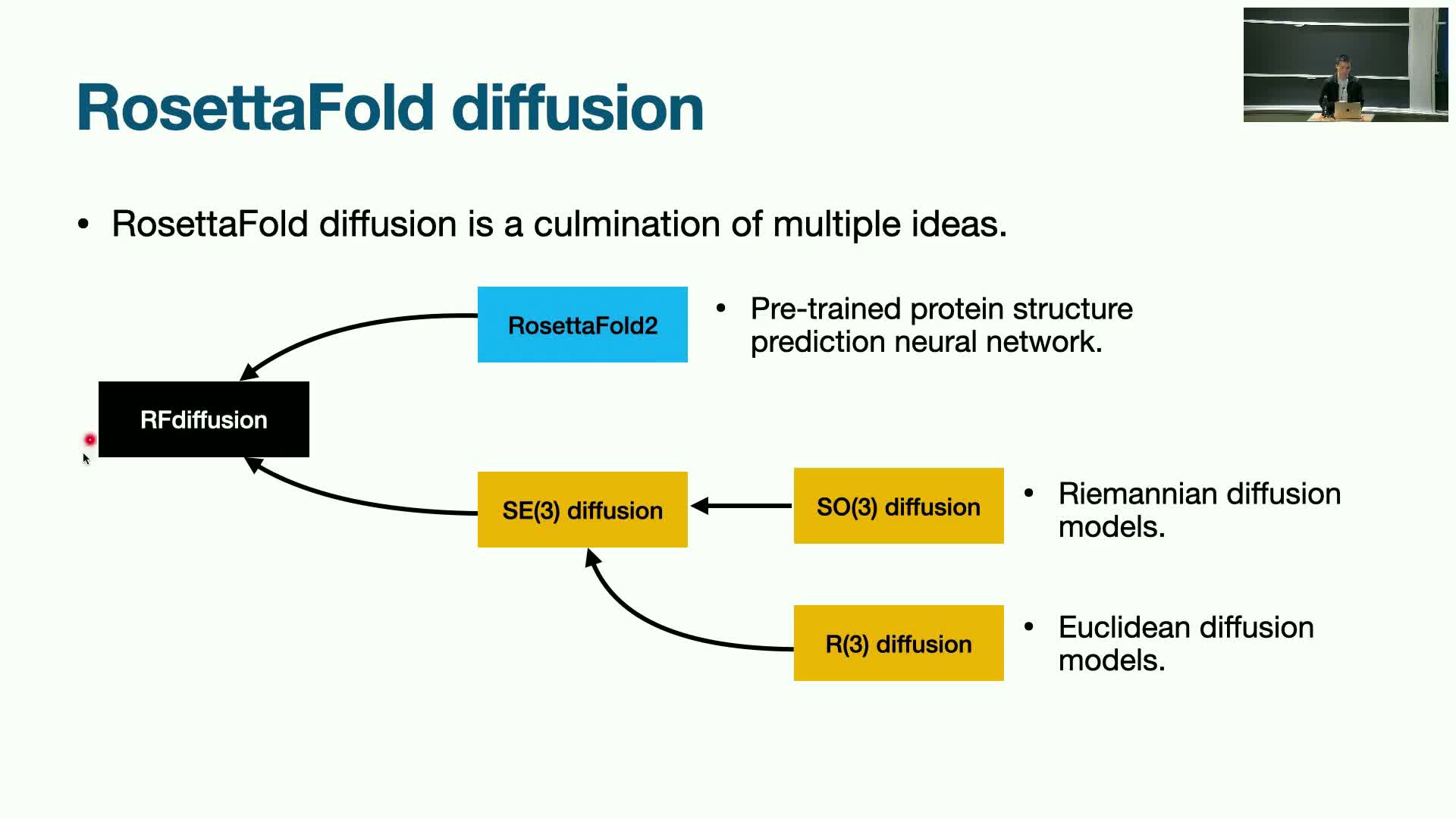

RFdiffusion: pretraining plus diffusion for large-scale conditional structure generation

RFdiffusion integrates a pre-trained structure-prediction architecture with diffusion-based fine-tuning to enable large-scale conditional structure generation up to substantially longer lengths than earlier models.

Key advantages of the approach:

-

Pretraining on structure-prediction tasks provides a strong inductive bias that accelerates diffusion fine-tuning and stabilizes long-chain generation.

- This combination allows generation of proteins hundreds to thousands of residues long.

-

RFdiffusion exhibits enhanced novelty and generalization beyond the training dataset while supporting conditional modes such as motif scaffolding and binder design.

Conclusion: pretraining followed by targeted diffusion fine-tuning offers a practical pathway to scale structure generative models.

Conditional generation primitives: symmetry, binder design, inpainting and classifier guidance

Conditional controls enable practical design tasks by biasing the generative process toward task-specific constraints:

-

Symmetric generation: enforce specified point-group symmetries.

-

Motif-scaffolding / inpainting: fill missing segments while preserving surrounding context.

-

Binder design: condition generation to produce proteins that envelop or interact with a target molecule or epitope.

Guidance mechanisms:

-

Classifier-guidance or potential fields can bias samples toward desired properties (e.g., attraction to a ligand position while applying repulsive terms to avoid atomic clashes).

- Combining multiple conditions (e.g., symmetry + motif scaffolding, binding location + topology constraints) yields rich, task-specific objectives and produces experimentally testable candidates tailored to functional requirements.

Experimental validation and empirical success rates for diffusion-based binder design

Diffusion-based conditional design pipelines have been taken to wet-lab validation and shown large improvements in experimental hit rates relative to prior methods that lacked high-quality structure generation.

Empirical outcomes:

- In several target families, designed binders generated by RFdiffusion were synthesized and assayed with success rates orders of magnitude higher than earlier pipelines that separated structure generation and sequence design.

-

Cryo-EM and other structural assays confirmed that some experimentally measured binder structures closely match the AI-generated models.

These results demonstrate that geometry-aware conditional generative models can produce viable, synthesizable protein binders and symmetric assemblies for biological applications.

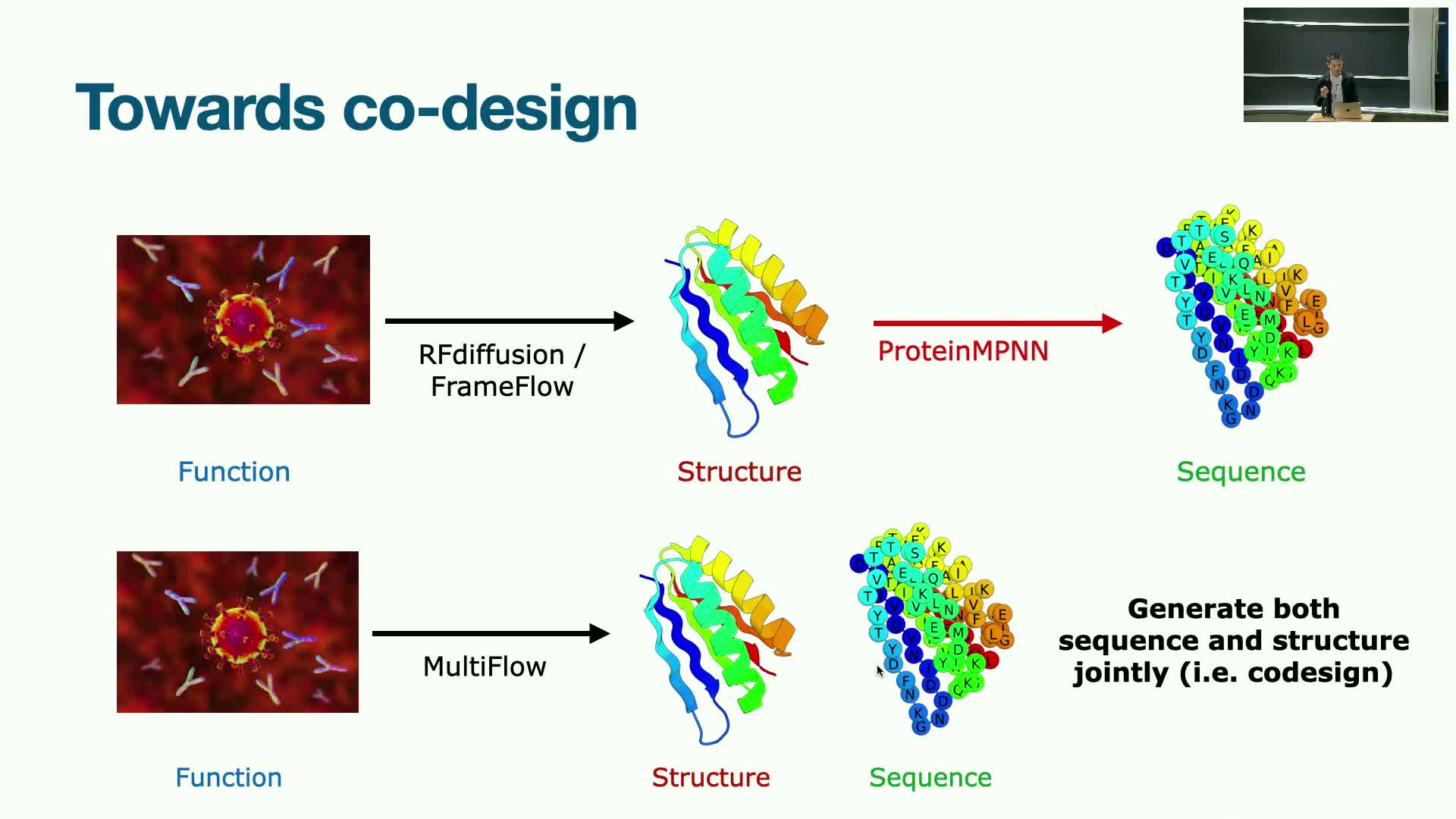

Codesign and Multiflow: joint generation of sequence and structure

Codesign aims to generate sequence and structure simultaneously to avoid the sequential chicken-and-egg problem of first designing structure then sequence.

Motivation and proposed approaches:

- Joint modeling can yield better coupling between sequence constraints and 3D geometry, improving realizability.

-

Multiflow is a proposed flow-matching formulation that operates over translations, rotations, and discrete sequence space, requiring hybrid methods to model continuous-time dynamics for discrete variables.

Technical and practical notes:

- The approach extends continuous optimal-transport-like matching to discrete distributions with technical adaptations.

- Enables any-order generation rather than strictly autoregressive left-to-right sampling.

Potential: joint sequence-structure generation can improve coherency between designed folds and realizable amino-acid sequences, reducing downstream mismatch between geometry and sequence constraints.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: